Book of Ezekiel

The Book of Ezekiel is the third of the Latter Prophets in the Tanakh and one of the major prophetic books in the Old Testament, following Isaiah and Jeremiah.[1] According to the book itself, it records six visions of the prophet Ezekiel, exiled in Babylon, during the 22 years from 593 to 571 BC, although it is the product of a long and complex history and does not necessarily preserve the very words of the prophet.[2]

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Tanakh (Judaism) | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Old Testament (Christianity) | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Bible portal | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

The visions, and the book, are structured around three themes: (1) Judgment on Israel (chapters 1–24); (2) Judgment on the nations (chapters 25–32); and (3) Future blessings for Israel (chapters 33–48).[3] Its themes include the concepts of the presence of God, purity, Israel as a divine community, and individual responsibility to God. Its later influence has included the development of mystical and apocalyptic traditions in Second Temple and rabbinic Judaism and Christianity.

Structure

Ezekiel has the broad three-fold structure found in a number of the prophetic books: oracles of woe against the prophet's own people, followed by oracles against Israel's neighbours, ending in prophecies of hope and salvation:

- Prophecies against Judah and Jerusalem, chapters 1–24

- Prophecies against the foreign nations, chapters 25–32

- Prophecies of hope and salvation, chapters 33–48.[4]

Summary

_-_Walters_44616.jpg)

The book opens with a vision of YHWH (יהוה). The book moves on to anticipate the destruction of Jerusalem and the Temple, explains this as God's punishment, and closes with the promise of a new beginning and a new Temple.[5]

- Inaugural vision Ezekiel 1:1–3:27: God approaches Ezekiel as the divine warrior, riding in his battle chariot. The chariot is drawn by four living creatures, each having four faces (those of a man, a lion, an ox, and an eagle) and four wings. Beside each "living creature" is a "wheel within a wheel", with "tall and awesome" rims full of eyes all around. God commissions Ezekiel as a prophet and as a "watchman" in Israel: "Son of man, I am sending you to the Israelites." (2:3)

- Judgment on Jerusalem and Judah[6] and on the nations:[7] God warns of the certain destruction of Jerusalem and of the devastation of the nations that have troubled his people: the Ammonites, Moabites, Edomites and Philistines, the Phoenician cities of Tyre and Sidon, and Egypt.

- Building a new city:[8] The Jewish exile will come to an end, a new city and new Temple will be built, and the Israelites will be gathered and blessed as never before.

Some of the highlights include:[9]

- The "throne vision", in which Ezekiel sees God enthroned in the Temple among the heavenly host;[10]

- The first "temple vision", in which Ezekiel sees God leave the Temple because of the abominations practiced there (meaning the worship of idols rather than YHWH, the official God of Judah;[11]

- Images of Israel, in which Israel is seen as a harlot bride, among other things;[12]

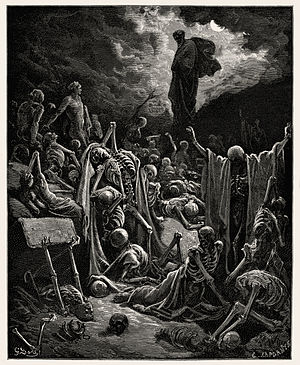

- The "valley of dry bones", in which the prophet sees the dead of the house of Israel rise again;[13]

- The destruction of Gog and Magog, in which Ezekiel sees Israel's enemies destroyed and a new age of peace established;[14]

- The final temple vision, in which Ezekiel sees a new commonwealth centered around a new temple in Jerusalem, sometimes called the Third Temple, to which God's Shekinah (Divine Presence) has returned [15]

Composition

Life and times of Ezekiel

The Book of Ezekiel describes itself as the words of the Ezekiel ben-Buzi, a priest living in exile in the city of Babylon between 593 and 571 BC. Most scholars today accept the basic authenticity of the book, but see in it significant additions by a "school" of later followers of the original prophet. According to Jewish tradition, the Men of the Great Assembly wrote the Book of Ezekiel, based on the prophet's words.[16] While the book exhibits considerable unity and probably reflects much of the historic Ezekiel, it is the product of a long and complex history and does not necessarily preserve the very words of the prophet.[2]

According to the book that bears his name, Ezekiel ben-Buzi was born into a priestly family of Jerusalem c.623 BC, during the reign of the reforming king Josiah. Prior to this time, Judah had been a vassal of the Assyrian empire, but the rapid decline of Assyria after c. 630 led Josiah to assert his independence and institute a religious reform stressing loyalty to Yahweh, the national God of Israel. Josiah was killed in 609 and Judah became a vassal of the new regional power, the Neo-Babylonian empire. In 597, following a rebellion against Babylon, Ezekiel was among the large group of Judeans taken into captivity by the Babylonians. He appears to have spent the rest of his life in Mesopotamia. A further deportation of Jews from Jerusalem to Babylon occurred in 586 when a second unsuccessful rebellion resulted in the destruction of the city and its Temple and the exile of the remaining elements of the royal court, including the last scribes and priests. The various dates given in the book suggest that Ezekiel was 25 when he went into exile, 30 when he received his prophetic call, and 52 at the time of the last vision c.571.[17]

Textual history

The Jewish scriptures were translated into Greek in the two centuries prior to the Common Era. The Greek version of these books is called the Septuagint. The Jewish Bible in Hebrew is called the Masoretic text (meaning passing down after a Hebrew word Masorah; for Jewish scholars and rabbis curated and commented on the text). The Greek (Septuagint) version of Ezekiel differs considerably from the Hebrew (Masoretic) version – it is shorter and possibly represents an early interpretation of the book we have today (according to the masoretic tradition) – while other ancient manuscript fragments differ from both.[18]

Critical history

The first half of the 20th century saw several attempts to deny the authorship and authenticity of the book, with scholars such as C. C. Torrey (1863–1956) and Morton Smith placing it variously in the 3rd century BC and in the 8th/7th. The pendulum swung back in the post-war period, with an increasing acceptance of the book's essential unity and historical placement in the Exile. The most influential modern scholarly work on Ezekiel, Walther Zimmerli's two-volume commentary, appeared in German in 1969 and in English in 1979 and 1983. Zimmerli traces the process by which Ezekiel's oracles were delivered orally and transformed into a written text by the prophet and his followers through a process of ongoing re-writing and re-interpretation. He isolates the oracles and speeches behind the present text, and traces Ezekiel's interaction with a mass of mythological, legendary and literary material as he developed his insights into Yahweh's purposes during the period of destruction and exile.[19]

Themes

As a priest, Ezekiel is fundamentally concerned with the Kavod YHWH, a technical phrase meaning the presence (shekhinah) of YHWH (i.e., one of the Names of God) among the people, in the Tabernacle, and in the Temple, and normally translated as "glory of God".[20] In Ezekiel the phrase describes God mounted on his throne-chariot as he departs from the Temple in chapters 1–11 and returns to what Marvin Sweeney describes as a portrayal of "the establishment of the new temple in Zion as YHWH returns to the temple, which then serves as the center for a new creation with the tribes of Israel arrayed around it" in chapters 40–48.[21] The vision in chapters 1:4–28 reflects common mythological/Biblical themes and the imagery of the Temple: God appears in a cloud from the north – the north being the usual home of God/the gods in ancient mythology and Biblical literature – with four living creatures corresponding to the two cherubim above the Mercy Seat of the Ark of the Covenant and the two in the Holy of Holies, the innermost chamber of the Temple; the burning coals of fire between the creatures perhaps represents the fire on the sacrificial altar, and the famous "wheel within a wheel" may represent the rings by which the Levites carried the Ark, or the wheels of the cart.[21]

Ezekiel depicts the destruction of Jerusalem as a purificatory sacrifice upon the altar, made necessary by the "abominations" in the Temple (the presence of idols and the worship of the god Tammuz) described in chapter 8.[22] The process of purification begins, God prepares to leave, and a priest lights the sacrificial fire to the city.[23] Nevertheless, the prophet announces that a small remnant will remain true to Yahweh in exile, and will return to the purified city.[23] The image of the valley of dry bones returning to life in chapter 37 signifies the restoration of the purified Israel.[23]

Previous prophets had used "Israel" to mean the northern kingdom and its tribes; when Ezekiel speaks of Israel he is addressing the deported remnant of Judah; at the same time, however, he can use this term to mean the glorious future destiny of a truly comprehensive "Israel".[24] In sum, the book describes God's promise that the people of Israel will maintain their covenant with God when they are purified and receive a "new heart" (another of the book's images) which will enable them to observe God's commandments and live in the land in a proper relationship with Yahweh.[25]

The theology of Ezekiel is notable for its contribution to the emerging notion of individual responsibility to God – each man would be held responsible only for his own sins. This is in marked contrast to the Deuteronomistic writers, who held that the sins of the nation would be held against all, without regard for an individual's personal guilt. Nonetheless, Ezekiel shared many ideas in common with the Deuteronomists, notably the notion that God works according to the principle of retributive justice and an ambivalence towards kingship (although the Deuteronomists reserved their scorn for individual kings rather than for the office itself). As a priest, Ezekiel praises the Zadokites over the Levites (lower level temple functionaries), whom he largely blames for the destruction and exile. He is clearly connected with the Holiness Code and its vision of a future dependent on keeping the Laws of God and maintaining ritual purity. Notably, Ezekiel blames the Babylonian exile not on the people's failure to keep the Law, but on their worship of gods other than Yahweh and their injustice: these, says Ezekiel in chapters 8–11, are the reasons God's Shekhinah left his city and his people.[26]

Later interpretation and influence

Second Temple and rabbinic Judaism (c. 515 BC–500 AD)

Ezekiel's imagery provided much of the basis for the Second Temple mystical tradition in which the visionary ascended through the Seven Heavens in order to experience the presence of God and understand his actions and intentions.[1] The book's literary influence can be seen in the later apocalyptic writings of Daniel and Zechariah. He is specifically mentioned by Ben Sirah (a writer of the Hellenistic period who listed the "great sages" of Israel) and 4 Maccabees (1st century AD). In the 1st century AD the historian Josephus said that the prophet wrote two books: he may have had in mind the Apocryphon of Ezekiel, a 1st-century BC text that expands on the doctrine of resurrection. Ezekiel appears only briefly in the Dead Sea Scrolls, but his influence there was profound, most notably in the Temple Scroll with its temple plans, and the defence of the Zadokite priesthood in the Damascus Document.[27] There was apparently some question concerning the inclusion of Ezekiel in the canon of scripture, since it is frequently at odds with the Torah (the five "Books of Moses" which are foundational to Judaism).[1]

Christianity

Ezekiel is referenced more in the Book of Revelation than in any other New Testament writing.[28] To take just two well-known passages, the famous Gog and Magog prophecy in Revelation 20:8 refers back to Ezekiel 38–39,[29] and in Revelation 21–22, as in the closing visions of Ezekiel, the prophet is transported to a high mountain where a heavenly messenger measures the symmetrical new Jerusalem, complete with high walls and twelve gates, the dwelling-place of God where his people will enjoy a state of perfect well-being.[30] Apart from Revelation, however, where Ezekiel is a major source, there is very little allusion to the prophet in the New Testament; the reasons for this are unclear, but it cannot be assumed that every Christian or Hellenistic Jewish community in the 1st century would have had a complete set of (Hebrew) scripture scrolls, and in any case Ezekiel was under suspicion of encouraging dangerous mystical speculation, as well as being sometimes obscure, incoherent, and pornographic.[31]

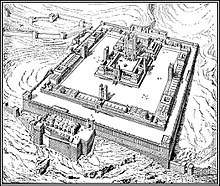

The Visionary Ezekiel Temple plan drawn by the 19th-century French architect and Bible scholar Charles Chipiez.

The Visionary Ezekiel Temple plan drawn by the 19th-century French architect and Bible scholar Charles Chipiez. The Vision of The Valley of The Dry Bones by Gustave Doré, 1866

The Vision of The Valley of The Dry Bones by Gustave Doré, 1866 Ezekiel's Vision of the Valley of Dry Bones by Maerten de Vos, c. 1600

Ezekiel's Vision of the Valley of Dry Bones by Maerten de Vos, c. 1600 Ezekiel's Vision of the Valley of Dry Bones by Quentin Metsys the Younger, c. 1589

Ezekiel's Vision of the Valley of Dry Bones by Quentin Metsys the Younger, c. 1589

See also

| Wikiquote has quotations related to: Book of Ezekiel |

| Wikisource has original text related to this article: |

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Book of Ezekiel. |

Citations

- Sweeney 1998, p. 88.

- Joyce 2009, p. 16.

- Petersen 2002, p. 140.

- McKeating 1993, p. 15.

- Redditt 2008, p. 148

- Ezekiel 4:1–24:27

- Ezekiel 25:1–32:32

- Ezekiel 33:1–48:35

- Blenkinsopp (1990)

- Ezekiel 1:4–28

- Ezekiel 8:1–16

- Ezekiel 15–19

- Ezekiel 37:1–14

- Ezekiel 38–39

- Ezekiel 40–48

- Babylonian Talmud, Baba Batra 15a

- Drinkard 1996, pp. 160–61.

- Blenkinsopp 1996, p. 130.

- Sweeney 1998, pp. 165–66.

- Sweeney 1998, p. 91.

- Sweeney 1998, p. 92.

- Sweeney 1998, pp. 92–93.

- Sweeney 1998, p. 93.

- Goldingay 2003, p. 624.

- Sweeney 1998, pp. 93–94.

- Kugler & Hartin 2009, p. 261.

- Block 1997, p. 43.

- Buitenwerf 2007, p. 165.

- Buitenwerf 2007, pp. 165 ff.

- Block 1998, p. 502.

- Muddiman 2007, p. 137.

Bibliography

- Bandstra, Barry L (2004). Reading the Old Testament: an introduction to the Hebrew Bible. Wadsworth. ISBN 9780495391050.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Blenkinsopp, Joseph (1996). A history of prophecy in Israel. Westminster John Knox Press. ISBN 9780664256395.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Blenkinsopp, Joseph (1990). Ezekiel. Westminster John Knox. ISBN 9780664237554.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Block, Daniel I. (1997). The Book of Ezekiel: chapters 1–24, Volume 1. Eerdmans. ISBN 9780802825353.

- Block, Daniel I. (1998). The Book of Ezekiel: chapters 25–48, Volume 2. Eerdmans. ISBN 9780802825360.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Brueggemann, Walter (2002). Reverberations of faith: a theological handbook of Old Testament themes. Westminster John Knox. ISBN 9780664222314.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Buitenwerf, Riuewerd (2007). "The Gog and Magog Tradition in Ezekiel 20:8". In De Jonge, H. J.; Tromp, Johannes (eds.). The Book of Ezekiel and Its Influence. Ashgate Publishing. ISBN 9780754655831.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Bullock, C. Hassell (1986). An Introduction to the Old Testament Prophetic Books. Moody Press. ISBN 9781575674360.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Clements, Ronald E (1996). Ezekiel. Westminster John Knox Press. ISBN 9780664252724.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Drinkard, Joel F. Jr. (1996). "Ezekiel". The Prophets. ISBN 9780865545090.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Eichrodt, Walther E (1996). Ezekiel. Westminster John Knox Press. ISBN 9780664227661.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Goldingay, John A. (2003). "Ezekiel". In James D. G. Dunn, John William Rogerson (ed.). Eerdmans Bible Commentary. Eerdmans. ISBN 9780802837110.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Henning III, Emil Heller (2012). Ezekiel's Temple: A Scriptural Framework Illustrating the Covenant of Grace. . Xulon. ISBN 9781626975132.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Joyce, Paul M. (2009). Ezekiel: A Commentary. Continuum. ISBN 9780567483614.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Kugler, Robert; Hartin, Patrick (2009). The Old Testament between theology and history: a critical survey. Eerdmans. ISBN 9780802846365.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Levin, Christoph L (2005). The Old testament: a brief introduction. Princeton University Press. ISBN 9780691113944.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- McKeating, Henry (1993). Ezekiel. Continuum. ISBN 9781850754282.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Muddiman, John (2007). "The So-Called Bridal Bath...". In De Jonge, H.J.; Tromp, Johannes (eds.). The Book of Ezekiel and Its Influence. Ashgate Publishing.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Petersen, David L (2002). The prophetic literature: an introduction. John Knox Press. ISBN 9780664254537.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Redditt, Paul L. (2008). Introduction to the Prophets. Eerdmans. ISBN 9780802828965.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Sweeney, Marvin A. (1998). "The Latter Prophets". In Steven L. McKenzie, Matt Patrick Graham (ed.). The Hebrew Bible today: an introduction to critical issues. Westminster John Knox Press. ISBN 9780664256524.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

External links

- Online translations

- English Translation of the Greek Septuagint Bible: Ezekiel

- Yechezkiel from Chabad.org

- BibleGateway (various translations)

Book of Ezekiel | ||

| Preceded by Jeremiah |

Hebrew Bible | Succeeded by The Twelve Prophets |

| Preceded by Lamentations |

Protestant Old Testament |

Succeeded by Daniel |

| Preceded by Baruch |

Roman Catholic Old Testament | |

| Preceded by Letter of Jeremiah |

E. Orthodox Old Testament | |