Bean Station, Tennessee

Bean Station is a town in Grainger and Hawkins counties in the state of Tennessee, United States.[8] As of the 2010 census, the population was 2,826.[5]

Bean Station, Tennessee | |

|---|---|

| Town of Bean Station | |

Bean Station Town Hall | |

Seal | |

| Nickname(s): The Crossroads[1] | |

| Motto(s): "A Historical Crossroad" | |

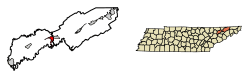

Location of Bean Station in Grainger and Hawkins counties in Tennessee | |

Bean Station Location of Bean Station in Grainger and Hawkins counties in Tennessee  Bean Station Bean Station (the United States) | |

| Coordinates: 36°20′37″N 83°17′03″W | |

| Country | United States |

| State | Tennessee |

| Counties | Grainger, Hawkins |

| Settled | 1776 |

| Incorporated | 1996 |

| Named for | William Bean or Bean family[2] |

| Government | |

| • Type | Mayor-Board of Aldermen |

| • Mayor | Ben Waller |

| • Vice Mayor | Jeff Atkins |

| • Aldermen | List of Aldermen

|

| Area | |

| • Total | 5.99 sq mi (15.51 km2) |

| • Land | 5.99 sq mi (15.51 km2) |

| • Water | 0.00 sq mi (0.01 km2) |

| Elevation | 1,148 ft (350 m) |

| Population | |

| • Total | 2,826 |

| • Estimate (2019)[6] | 3,113 |

| • Density | 519.87/sq mi (200.72/km2) |

| Time zone | UTC-5 (Eastern (EST)) |

| • Summer (DST) | UTC-4 (EDT) |

| ZIP code | 37708 |

| Area code(s) | 865, 423 |

| GNIS feature ID | 1276544[7] |

| FIPS code | 47-03760 |

Bean Station is located primarily at the junction of U.S. Route 11W and U.S. Route 25E, in the easternmost part of Grainger County. It is considered a popular lakeside resort town appealing to retirees and tourists, and a commuter town for the city of Morristown in neighboring Hamblen County.

It is part of both the Knoxville Metropolitan Statistical Area and the Morristown Metropolitan Statistical Area.[9]

History

Early years and settlement

Bean Station was settled as a frontier outpost established in the late 1780s by the sons of William Bean, one of the earliest settlers in Tennessee. The land had likely been observed by Bean while on a long hunting excursion with Daniel Boone years prior. The outpost was situated at the intersection of the Wilderness Road, a north–south pathway that roughly followed what is present-day U.S. Route 25E, and the Old Stage Road, an east–west pathway that roughly followed what is now U.S. Route 11W. This heavily trafficked crossroads location made Bean Station an important stopover for early travelers, with taverns and inns were operating at the station by the early 1800s.[10]

Battle of Bean’s Station and the Civil War

During the Civil War, the Battle of Bean's Station took place in the westernmost area of the community on December 14, 1863. Confederate Army General, James Longstreet, attempted to capture Bean Station en route to Rogersville after failing to drive Union forces out of Knoxville. Bean Station was held by a contingent of Union soldiers under the command of General James M. Shackelford. After two days of gruesome fighting, Union forces were forced to retreat.[10]

Peavine Railroad

From the late 19th century until the early 20th century, Bean Station was a stop along the Knoxville and Bristol Railroad, commonly known by locals as the Peavine Railroad. The railroad was a branch line of the Southern Railway that ran from Morristown to Corryton, a bedroom community outside of Knoxville.[11] The Peavine Railroad had first operated between Morristown and Bean Station, with plans to connect north to the Cumberland Gap, but instead extended west through Grainger County towards Knoxville.[12] The Tate Springs resort located nearby to Bean Station, had its peak popularity between the 1890s and 1920s when the Peavine Railroad provided passenger rail connections to the site.[13]

Construction of Cherokee Dam and relocation

The construction of Cherokee Dam by the Tennessee Valley Authority (TVA) several miles downstream along the Holston River in 1941 had plans that included impounding the site where the town was originally settled.[14]

In 1941, officials from TVA and concerned community members gathered to discuss the future of the town and its relocation efforts. A planning commission from the state government and TVA personnel developed plans for sites for Bean Station to relocate to. After controversy arose from negotiations from unwilling property owners and reluctance from citizens to relocate as a community, the planned community relocation project was abandoned, with the citizens relocating on their own will.[14]

Many citizens were relocated and many houses and other structures were demolished or moved. A large portion of the community was impounded, and at least one historical structure had to be relocated.[10]

1950s to present day

In 1967, a group of area residents organized and chartered the Bean Station Volunteer Fire Department.[1] Eight years later, the Bean Station Volunteer Rescue Squad was organized and chartered.[1]

Through the mid-20th century, Bean Station saw positive growth in population and economic progress as the community's two main transportation routes, U.S. Routes 11W and 25E were used prominently for the trucking industry, making the community a popular truck stop. As the region's economy began to diversify, manufacturing soon took over agriculture as the area's main source of income.[15]

In 1995, US-11W and US-25E were re-routed and widened into a four-lane divided-highway, bypassing the then unincorporated area's central business district and prompting several businesses to relocate onto the new bypass.[15]

1972 US-11W bus/semi-truck collision

On May 13, 1972, 14 people were killed and 15 injured in a head-on collision between a double-decker Greyhound bus and a tractor-trailer on U.S. Route 11W in Bean Station during its unincorporated era.[16][17] The accident is considered one of the deadliest and worst traffic collisions in the history of the state of Tennessee.[18][19] The accident led to outcry from politicians and citizens calling for traffic safety and infrastructure improvements, such as highway widenings, and the completion of Interstate 81 in Tennessee.[20]

Incorporation and present day

As the population of the Bean Station area grew through-out the later 20th century, and the possibility of being annexed into the neighboring Morristown-Hamblen area,[15] residents gathered to incorporate Bean Station into a city. There were several attempts at incorporating the area that were never successful until 1994.[1] Bean Station was incorporated into a city of 2,171 residents by referendum in 1996.[21][1][22]

On May 23, 2013, an ex-police officer for the town shot four people in a pharmacy in downtown Bean Station, killing two. The following day, a vigil was held for the two victims with an estimated attendance of 300 individuals.[23]

Geography

Bean Station is located in rural easternmost Grainger County, where it borders the unincorporated community of Mooresburg at the line between Grainger and Hawkins counties. The town is situated in the Richland Valley (also known as Mooresburg Valley) with Clinch Mountain to the north and Cherokee Lake to the south. In the western of portion of Bean Station adjacent to Kingswood Home for Children on the Tate Springs resort site, two major highways merge, with U.S. Route 25E entering from the northwest, and U.S. Route 11W entering from the southwest. From this point, US-25E leads over Clinch Mountain 20 miles (32 km) to Tazewell in Claiborne County, while US-11W runs west through the Richland Valley 11 miles (18 km) to Rutledge, the seat of Grainger County. The highways split again just south of Bean Station's central business district, with 11W bypassing the business district and continining northeastward 17 miles (27 km) to Rogersville, and 25E continuing southward across Cherokee Lake into Hamblen County, 10 miles (16 km) to Morristown.

Tennessee State Route 375 (also known as Lakeshore Drive) also intersects US-25E south of the business district, which traverses into several of Bean Station’s affluent outskirt lakefront neighborhoods and subdivisions.

According to the U.S. Census Bureau, Bean Station has an area of 5.4 square miles (14.0 km2), of which 0.436 acres (1,763 m2), or 0.01%, are water.[5] The town limits include Wyatt Village, located next to an arm of Cherokee Lake along US-25E south of downtown, and portions of Tate Springs located near US-11W and Briar Fork Creek on Cherokee Lake. The town limits stretch 8 miles (13 km) along US-25E to Olen R. Marshall Bridge across Cherokee Lake, and 4 miles (6.4 km) along US-11W to Bean Station Elementary School.

Neighborhoods

- Bayside

- Campbell Heights

- Clinchview Landing

- Country Club Hills

- Crosby Park

- Gammon Springs

- Hillview Acres

- Lakeview Estates

- Leon Rock

- Livingston Heights

- Meadow Branch

- Meadow Creek Estates

- Shields Crossing

- Tanglewood

- Tate Springs

- Wyatt Village

Demographics

| Historical population | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Census | Pop. | %± | |

| 2000 | 2,514 | — | |

| 2010 | 2,826 | 12.4% | |

| Est. 2019 | 3,113 | [6] | 10.2% |

| Sources:[24] | |||

Population

As of the 2010 United States Census, there were 2,826 people, 1,149 households, and 827 families residing in the town.

Ethnicity

96.8% were White, 0.6% Black or African American, 0.5% Native American, 0.1% Asian and 0.7% of two or more races. 2.3% were Hispanic or Latino (of any race).

Age distribution

The average household size was 2.46 and the average family size was 2.88. 25% of households had children under the age of 18 living with them, 51.8% were married couples living together, 6.3% had a male householder with no wife present, and 13.9% were female householders with no husband present. 28% of households were non-families. The median age of residents in the town was 47.8. 21.7% of residents were under the age of 18, and 16.2% were age 65 years or older.

Economy

Retail and commerce

In its retail and commercial markets, Bean Station has a small selection of restaurants and stores. A family-operated IGA Market is the only grocery store in Bean Station area.[25]

Industry and manufacturing

Bean Station is home to a furniture manufacturing facility,[26] a Clayton Homes manufacturing facility,[27] and a construction materials supplier.[28]

Commuting

72% of the town’s population commute outside of Grainger County for work, with most finding employment in Morristown.[29] The average commute time for Bean Station residents is 24 minutes.[30]

Wastewater

Since the town's incorporation, officials have expressed interest in constructing a sewage treatment system.[22]

The first attempt of sewer coming to the town was proposed in 2007, when Grainger County was awarded $1.5 million dollars from the Economic Development Administration to construct a regional wastewater system and a new outfall line in the eastern part of the county, including Bean Station.[31] The overall $4.8 million project included the construction of a regional collection system with developers planning to establish lakefront resort developments and retail establishments, creating nearly 400 jobs and generating an estimated $83.2 million in private investment.[31][32][33] In 2009, after several developers pulled out of the project, negotiations between Bean Station and neighboring Morristown began about adding a sewage line from Morristown's main treatment plant across the Olen R. Marshall Bridge over Cherokee Lake, eliminating the need of constructing a treatment plant in Bean Station.[34] The project was later cancelled in 2011 by town and county officials after developers and Morristown officials pulled out their plans because of the abrupt financial crisis of 2007–2008.[31][35]

The issue of sewer was brought back in 2018, as the town gathered with officials from Kingswood Home For Children, economic development officals, and engineers, proposing plans to construct a 10,000 gallons-per-day treatment plant on the shelter's site and add lines from the plant to Bean Station over several phases.[36] The town received nearly $515,000 in funding, including a $340,000 grant from the Appalachian Regional Commission.[37]

A preliminary engineering report prepared for Bean Station by the engineering consulting firm said that a public sewer system would create "growth opportunities" for the town that would not be available without a sewer system, and reduce septic system failures in the town.[38] In early 2019, the Bean Station Town Council delayed actions to go forward with the project, with an unknown timeframe timeframe to vote on the issue.[39][40]

Arts and culture

Since 1996, the town hosts an annual harvest festival in its downtown district celebrating the area's agricultural and craftsmanship scenes.[22] The festival attracts thousands of festival-goers and tourists alike every third weekend in October.[41][42] In 2007, the town made national headlines after breaking a Guinness World Record for the world's largest pot of beans at the 11th annual Harvest Pride festival, with the pot holding 600 gallons of baked beans.[41][43][44]

Parks and recreation

The town is considered popular with boaters and anglers alike due to its access to Cherokee Lake.[22] Clinch Mountain, located nearby to the town, provides the opportunity for hiking.[22]

Parks and public recreation areas include:

Government

Municipal

Bean Station uses the mayor-aldermen system, which was established in 1996 when the town was incorporated. It is governed locally by a five-member Board of Mayor and Aldermen.

The citizens elect the mayor and four aldermen to four-year terms. The board elects a vice mayor from among the four aldermen.

State

Bean Station is represented in the 35th District of the Tennessee House of Representatives by Jerry Sexton, a Republican.[49]

It is represented in the 8th District of the Tennessee Senate by Frank Niceley, also a Republican.[50]

Federal

Bean Station is represented in the United States House of Representatives by Republican Tim Burchett of the 2nd congressional district.[51]

Education

Bean Station Elementary School, located at the westernmost part of the town, is operated by the Grainger County Department of Education. Elementary students attend Bean Station Elementary, middle school students attend Rutledge Middle, and high school students attend Grainger High School in Rutledge, along with other students in the Grainger County Schools District, excluding the Washburn area.[52]

Media

Newspaper

- Grainger Today

In film

The 1981 horror film, The Evil Dead, had filmed a part of its opening scene in the northern Grainger County, and in Bean Station along Old U.S. Route 25E near Bean Station Elementary School.[53]

Notable people

- Peter Ellis Bean - filibuster[54]

- Robert E. Preston - Director of United States Mint[55]

- William Tandy Senter - politician[56]

- Jerry Sexton - politician[57]

- John K. Shields - United States Senator[10]

References

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Bean Station, Tennessee. |

- Grainger County Heritage Book Committee (January 1, 1998). Grainger County, Tennessee and Its People 1796-1998. Walsworth Publishing. Retrieved August 7, 2020.

- Miller, Larry (2001). Tennessee Place Names. Indiana University Press. p. 14. ISBN 0-253-33984-7. Retrieved June 25, 2020.

- University of Tennessee, Municipal Technical Advisory Service. "Bean Station". MTAS.tennessee.edu. Retrieved June 22, 2020.

- "2019 U.S. Gazetteer Files". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved July 30, 2020.

- "Geographic Identifiers: 2010 Demographic Profile Data (G001): Bean Station city, Tennessee". American Factfinder. U.S. Census Bureau. Retrieved February 17, 2017.

- "Population and Housing Unit Estimates". United States Census Bureau. May 24, 2020. Retrieved May 27, 2020.

- "Bean Station". Geographic Names Information System. United States Geological Survey.

- Bobo, Jeff (February 5, 2020). "2020 a big year for Hawkins BOE, municipal elections". Kingsport Times-News. Retrieved July 27, 2020.

In Bean Station, which has a small section in Hawkins County, the alderman seats held by Patsy Harrell and Jeff Atkins are up for re-election.

- "Revised Delineations of Metropolitan Statistical Areas, Micropolitan Statistical Areas, and Combined Statistical Areas, and Guidance on Uses of the Delineations of These Areas" (PDF). Office of Management and Budget. Retrieved April 27, 2014.

- Coffey, Ken. "History of Bean Station". Town of Bean Station. Archived from the original on July 24, 2015. Retrieved July 23, 2015.

- Faulkner, Charles (1985). "Industrial Archaeology of the "Peavine Railroad": An Archaeological and Historical Study of an Abandoned Railroad in East Tennessee". Tennessee Historical Quarterly. Tennessee Historical Society. 44 (1): 40–58. Retrieved August 7, 2020.

- Hill, Howard (January 20, 1957). "The Old Peavine Railroad". Morristown Daily Gazette and Mail. Retrieved August 7, 2020.

- West, Carroll Van (1995). Tennessee's Historic Landscapes: A Traveler's Guide. University of Tennessee Press. pp. 166–167. ISBN 9780870498817.

- Tennessee Valley Authority (1946). The Cherokee Project: A Comprehensive Report on the Planning, Design, Construction, and Initial Operations of the Cherokee Project. Washington D.C.: United States Government Printing Office. p. 249.

- "A Brief History of Bean Station". City of Bean Station. Archived from the original on February 4, 2005. Retrieved August 7, 2020.

- "14 Die in Tennessee Bus Truck Crash". New York Times. May 14, 1972. Retrieved May 6, 2020.

- Wolfe, Tracey (June 24, 2020). "Victim reunites with rescue workers 48 years after deadly crash". Grainger Today. Retrieved June 25, 2020.

- Lakin, Matt (August 26, 2012). "Blood on the asphalt: 11W wreck left 14 people dead". Knoxville News Sentinel. Retrieved May 6, 2020.

- Ahillen, Steve (October 3, 2013). "Jefferson wreck echoes Tennessee's most deadly bus accident". Knoxville News Sentinel. Retrieved July 14, 2020.

- Beitler, Stuart (May 14, 1972). "11-W Disaster Brings New Highway Pleas". Kingsport Times-News.

- "Petition for incorporation election for the City of Bean Station - Tennessee". Municipal Technology Advisory Service. 1996. Retrieved July 29, 2020.

- "About Bean Station". City of Bean Station. Archived from the original on February 4, 2005. Retrieved August 7, 2020.

- Coleman, Lance (May 24, 2013). "Police: Bean Station pharmacy victims shot execution-style". The Knoxville News Sentinel. Retrieved June 7, 2020.

- "Census of Population and Housing: Decennial Censuses". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved 2012-03-04.

- "Holt's Food Center IGA". https://www.holtsfoodcenter.iga.com/. Retrieved June 26, 2020. External link in

|website=(help) - "Sexton Furniture Manufacturing LLC". Bloomberg. Retrieved June 26, 2020.

- "Norris Homes by Clayton Homes". Norris Homes. Retrieved May 8, 2020.

- Vulcan Materials. "Facilties". vulcanmaterials.com. Retrieved June 7, 2020.

- East Tennessee Development District (April 1, 2012). "Grainger County 2010 Census Report" (PDF). ETDD.org. Retrieved May 8, 2020.

- "Bean Station, TN". DataUSA.io. Retrieved May 18, 2020.

- Hipsher, Mark (August 18, 2011). "Grainger County, TN - 04-01-05953" (PDF). Tennessee Department of Environment & Conservation.

- "Grainger County Awarded Grant to Expand Wastewater Treatment Plant". Office of Senator Lamar Alexander. September 21, 2007. Retrieved August 9, 2020.

- "Summary of EDA Investments". Economic Development Administration. Archived from the original on December 13, 2007. Retrieved August 11, 2020.

- "Sewer plan means no treatment plant". Grainger Today. February 11, 2009. Archived from the original on February 14, 2009. Retrieved August 9, 2020.

Mark Hipsher said Monday negotiations between the city of Bean Station and the city of Morristown for treating sewage on the east end of the county will eliminate the need for a wastewater treatment plant and simply requires infrastructure for piping sewage through a pumping station to the Morristown plant.

- Wilson, Tracey (April 30, 2011). "Aldermen clog sewer: $1.5 million grant down the drain". Grainger Today. Archived from the original on April 30, 2011. Retrieved July 24, 2020.

Citizens of Bean Station lost the opportunity to benefit from a $1.5 million grant for the implementation of Phase II of the Eastern Grainger County Sewer Project at the Board of Mayor and Aldermen meeting Monday.

- Fulghum Macindoe & Associates Inc. (March 12, 2019). "Bean Station, Tennessee Wastewater Treatment Master Plan" (PDF). Tennessee Department of Environment and Conservation. Retrieved August 10, 2020.

- "ARC Projects Approved in Fiscal Year 2018" (PDF). Appalachian Regional Commission. Retrieved August 10, 2020.

- Fulghum Macindoe & Associates Inc. (September 10, 2018). "PRELIMINARY ENGINEERING REPORT FOR TOWN OF BEAN STATION KINGSWOOD HOME FOR THE CHILDREN WASTEWATER TREATMENT PLANT REPLACEMENT AND SEWER REHABILITATION 2018 ARC" (PDF). Retrieved June 16, 2020.

- Hightower, Cliff (January 29, 2019). "Bean Station Council delays wastewater plant decision". The Citizen Tribune.

- Littleton, Wade (March 13, 2019). "Bean Station officials talk sewer at special-called meeting". Citizen Tribune. Retrieved 2020-05-29.

- Cason, Steve. "City to cook the world's largest pot of beans" (PDF). City of Bean Station. Archived from the original (PDF) on May 9, 2008. Retrieved August 9, 2020.

- Littleton, Wade (October 19, 2019). "Harvest Pride Festival attracts hundreds". The Citizen Tribune. Retrieved June 17, 2020.

- Branston, John (September 7, 2007). "Tennessee City Gassed Over World Record Pot of Beans". The Memphis Flyer. Retrieved July 12, 2020.

- "Bean festival scores an appropriate sponsor". AdWeek. October 23, 2007. Retrieved July 12, 2020.

- "Cherokee Reservoir". Tennessee Valley Authority. Retrieved July 14, 2020.

- "Boating Ramps and Access". Tennessee Wildlife Resources Agency. Retrieved July 14, 2020.

- "Lakeside Marina". lakeside-marina.com. Retrieved July 1, 2020.

- ThemeFuse. "Memberships | Clinchview Golf Club". clinchviewgolfclub.net. Retrieved 2017-11-14.

- "Representative Jerry Sexton". capitol.tn.gov. Retrieved June 25, 2020.

- "Senator Frank S. Niceley". capitol.tn.gov. Retrieved June 25, 2020.

- "Our District". Congressman Tim Burchett. Retrieved June 25, 2020.

- "Schools". Grainger County Schools. Retrieved July 3, 2020.

- "Locations". bookofthedead.ws. Retrieved July 12, 2020.

- Weems, John Edward. "Bean, Peter Ellis". Handbook of Texas Online. Retrieved July 30, 2020.

- Current History and Modern Culture: 1893. 3. Current History Company. 1894. p. 499.

- Biographical Directory of the American Congress 1774-1971. U.S. Government. 1971. p. 1677.

- "TN House Passes Bill for Monument to Unborn". WJHL. April 21, 2018.