German Peasants' War

The German Peasants' War, Great Peasants' War or Great Peasants' Revolt (German: Deutscher Bauernkrieg) was a widespread popular revolt in some German-speaking areas in Central Europe from 1524 to 1525. It failed because of intense opposition from the aristocracy, who slaughtered up to 100,000 of the 300,000 poorly armed peasants and farmers.[1] The survivors were fined and achieved few, if any, of their goals. Like the preceding Bundschuh movement and the Hussite Wars, the war consisted of a series of both economic and religious revolts in which peasants and farmers, often supported by Anabaptist clergy, took the lead. The German Peasants' War was Europe's largest and most widespread popular uprising prior to the French Revolution of 1789. The fighting was at its height in the middle of 1525.

| German Peasants' War | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the European wars of religion and the Protestant Reformation | |||||||

Map showing the locations of the peasant uprisings and major battles | |||||||

| |||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

|

|

partly: | ||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

|

Thomas Müntzer † Michael Gaismair Hans Müller † Jakob Rohrbach Wendel Hipler † Florian Geyer † Bonaventura Kuerschner |

| ||||||

| Strength | |||||||

| 300,000 | 6,000–8,500 | ||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||

| >100,000 | Minimal | ||||||

| Part of a series on the |

| Reformation |

|---|

|

|

Contributing factors |

|

Theologies of seminal figures |

|

|

By location |

|

Major political leaders |

|

Counter-Reformation |

|

Art and literature Painting and sculpture

Building Literature Theater |

|

Music Forms

Liturgies

Hymnals

Secular Music |

|

Conclusion and commemorations Conclusion

Monuments Calendrical commemoration |

| Protestantism |

| Part of a series on |

| Anabaptism |

|---|

Dirk Willems (picture) saves his pursuer. This act of mercy led to his recapture, after which he was burned at the stake near Asperen (etching from Jan Luyken in the 1685 edition of Martyrs Mirror) |

|

Background |

|

Distinctive doctrines |

|

Largest groups |

|

Related movements |

|

|

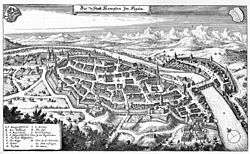

The war began with separate insurrections, beginning in the southwestern part of what is now Germany and Alsace, and spread in subsequent insurrections to the central and eastern areas of Germany and present-day Austria.[2] After the uprising in Germany was suppressed, it flared briefly in several Swiss cantons.

In mounting their insurrection, peasants faced insurmountable obstacles. The democratic nature of their movement left them without a command structure and they lacked artillery and cavalry. Most of them had little, if any, military experience. Their opposition had experienced military leaders, well-equipped and disciplined armies, and ample funding.

The revolt incorporated some principles and rhetoric from the emerging Protestant Reformation, through which the peasants sought influence and freedom. Radical Reformers and Anabaptists, most famously Thomas Müntzer, instigated and supported the revolt. In contrast, Martin Luther and other Magisterial Reformers condemned it and clearly sided with the nobles. In Against the Murderous, Thieving Hordes of Peasants, Luther condemned the violence as the devil's work and called for the nobles to put down the rebels like mad dogs.[3] Historians have interpreted the economic aspects of the German Peasants' War differently, and social and cultural historians continue to disagree on its causes and nature.

Background

In the sixteenth century, many parts of Europe had common political links within the Holy Roman Empire, a decentralized entity in which the Holy Roman Emperor himself had little authority outside of his own dynastic lands, which covered only a small fraction of the whole. At the time of the Peasants' War, Charles V, King of Spain, held the position of Holy Roman Emperor (elected in 1519). Aristocratic dynasties ruled hundreds of largely independent territories (both secular and ecclesiastical) within the framework of the empire, and several dozen others operated as semi-independent city-states. The princes of these dynasties were taxed by the Roman Catholic church. The princes stood to gain economically if they broke away from the Roman church and established a German church under their own control, which would then not be able to tax them as the Roman church did. Most German princes broke with Rome using the nationalistic slogan of "German money for a German church".[4]

Roman civil law

Princes often attempted to force their freer peasants into serfdom by increasing taxes and introducing Roman civil law. Roman civil law advantaged princes who sought to consolidate their power because it brought all land into their personal ownership and eliminated the feudal concept of the land as a trust between lord and peasant that conferred rights as well as obligations on the latter. By maintaining the remnants of the ancient law which legitimized their own rule, they not only elevated their wealth and position in the empire through the confiscation of all property and revenues, but increased their power over their peasant subjects.

During the Knights' Revolt the "knights", the lesser landholders of the Rhineland in western Germany, rose up in rebellion in 1522–1523. Their rhetoric was religious, and several leaders expressed Luther's ideas on the split with Rome and the new German church. However, the Knights' Revolt was not fundamentally religious. It was conservative in nature and sought to preserve the feudal order. The knights revolted against the new money order, which was squeezing them out of existence.[5]

Luther and Müntzer

Martin Luther, the dominant leader of the Reformation in Germany, initially took a middle course in the Peasants' War, by criticizing both the injustices imposed on the peasants, and the rashness of the peasants in fighting back. He also tended to support the centralization and urbanization of the economy. This position alienated the lesser nobles, but shored up his position with the burghers. Luther argued that work was the chief duty on earth; the duty of the peasants was farm labor and the duty of the ruling classes was upholding the peace. He could not support the Peasant War because it broke the peace, an evil he thought greater than the evils the peasants were rebelling against. At the peak of the insurrection in 1525, his position shifted completely to support of the rulers of the secular principalities and their Roman Catholic allies. In Against the Robbing Murderous Hordes of Peasants he encouraged the nobility to swiftly and violently eliminate the rebelling peasants, stating,"[the peasants] must be sliced, choked, stabbed, secretly and publicly, by those who can, like one must kill a rabid dog."[6] After the conclusion of the Peasants War, he was criticized for his writings in support of the violent actions taken by the ruling class. He responded by writing an open letter to Caspar Muller, defending his position. However, he also stated that the nobles were too severe in suppression of the insurrection, despite having called for severe violence in his previous work.[7] Luther has often been sharply criticized for his position.[8]

Thomas Müntzer was the most prominent radical reforming preacher who supported the demands of the peasantry, including political and legal rights. Müntzer's theology had been developed against a background of social upheaval and widespread religious doubt, and his call for a new world order fused with the political and social demands of the peasantry. In the final weeks of 1524 and the beginning of 1525, Müntzer travelled into south-west Germany, where the peasant armies were gathering; here he would have had contact with some of their leaders, and it is argued that he also influenced the formulation of their demands. He spent several weeks in the Klettgau area, and there is some evidence to suggest that he helped the peasants to formulate their grievances. While the famous Twelve Articles of the Swabian peasants were certainly not composed by Müntzer, at least one important supporting document, the Constitutional Draft, may well have originated with him.[9] Returning to Saxony and Thuringia in early 1525, he assisted in the organisation of the various rebel groups there and ultimately led the rebel army in the ill-fated Battle of Frankenhausen on 15 May 1525.[10] Müntzer's role in the Peasant War has been the subject of considerable controversy, some arguing that he had no influence at all, others that he was the sole inspirer of the uprising. To judge from his writings of 1523 and 1524, it was by no means inevitable that Müntzer would take the road of social revolution. However, it was precisely on this same theological foundation that Müntzer's ideas briefly coincided with the aspirations of the peasants and plebeians of 1525: viewing the uprising as an apocalyptic act of God, he stepped up as 'God's Servant against the Godless' and took his position as leader of the rebels.[11]

Luther and Müntzer took every opportunity to attack each other's ideas and actions. Luther himself declared against the moderate demands of the peasantry embodied in the twelve articles. His article Against the Murderous, Thieving Hordes of Peasants appeared in May 1525 just as the rebels were being defeated on the fields of battle.

Social classes in the 16th century Holy Roman Empire

In this era of rapid change, modernizing princes tended to align with clergy burghers against the lesser nobility and peasants.

Princes

Many rulers of Germany's various principalities functioned as autocratic rulers who recognized no other authority within their territories. Princes had the right to levy taxes and borrow money as they saw fit. The growing costs of administration and military upkeep impelled them to keep raising demands on their subjects.[12] The princes also worked to centralize power in the towns and estates.[13] Accordingly, princes tended to gain economically from the ruination of the lesser nobility, by acquiring their estates. This ignited the Knights' Revolt that occurred from 1522 through 1523 in the Rhineland. The revolt was "suppressed by both Catholic and Lutheran princes who were satisfied to cooperate against a common danger".[12]

To the degree that other classes, such as the bourgeoisie,[14] might gain from the centralization of the economy and the elimination of the lesser nobles' territorial controls on manufacture and trade,[15] the princes might unite with the burghers on the issue.[12]

Lesser nobility

The innovations in military technology of the Late Medieval period began to render the lesser nobility (the knights) militarily obsolete.[15] The introduction of military science and the growing importance of gunpowder and infantry lessened the importance of heavy cavalry and of castles. Their luxurious lifestyle drained what little income they had as prices kept rising. They exercised their ancient rights in order to wring income from their territories.[14]

In the north of Germany many of the lesser nobles had already been subordinated to secular and ecclesiastical lords.[15] Thus, their dominance over serfs was more restricted. However, in the south of Germany their powers were more intact. Accordingly, the harshness of the lesser nobles' treatment of the peasantry provided the immediate cause of the uprising. The fact that this treatment was worse in the south than in the north was the reason that the war began in the south.[12]

The knights became embittered as their status and income fell and they came increasingly under the jurisdiction of the princes, putting the two groups in constant conflict. The knights also regarded the clergy as arrogant and superfluous, while envying their privileges and wealth. In addition, the knights' relationships with the patricians in the towns was strained by the debts owed by the knights.[16] At odds with other classes in Germany, the lesser nobility was the least disposed to the changes.[14]

They and the clergy paid no taxes and often supported their local prince.[12]

Clergy

The clergy in 1525 were the intellectuals of their time. Not only were they literate, but in the Middle Ages they had produced most books. Some clergy were supported by the nobility and the rich, while others appealed to the masses. However, the clergy was beginning to lose its overwhelming intellectual authority. The progress of printing (especially of the Bible) and the expansion of commerce, as well as the spread of renaissance humanism, raised literacy rates, according to Engels.[17] Engels held that the Catholic monopoly on higher education was accordingly reduced. However, despite the secular nature of nineteenth century humanism, three centuries earlier Renaissance humanism had still been strongly connected with the Church: its proponents had attended Church schools.

Over time, some Catholic institutions had slipped into corruption. Clerical ignorance and the abuses of simony and pluralism (holding several offices at once) were rampant. Some bishops, archbishops, abbots and priors were as ruthless in exploiting their subjects as the regional princes.[18] In addition to the sale of indulgences, they set up prayer houses and directly taxed the people. Increased indignation over church corruption had led the monk Martin Luther to post his 95 Theses on the doors of the Castle Church in Wittenberg, Germany, in 1517, as well as impelling other reformers to radically re-think church doctrine and organization.[19][20] The clergy who did not follow Luther tended to be the aristocratic clergy, who opposed all change, including any break with the Roman Church.[21]

The poorer clergy, rural and urban itinerant preachers who were not well positioned in the church, were more likely to join the Reformation.[22] Some of the poorer clergy sought to extend Luther's equalizing ideas to society at large.

Patricians

Many towns had privileges that exempted them from taxes, so that the bulk of taxation fell on the peasants. As the guilds grew and urban populations rose, the town patricians faced increasing opposition. The patricians consisted of wealthy families who sat alone in the town councils and held all the administrative offices. Like the princes, they sought to secure revenues from their peasants by any possible means. Arbitrary road, bridge, and gate tolls were instituted at will. They gradually usurped the common lands and made it illegal for peasants to fish or to log wood from these lands. Guild taxes were exacted. No revenues collected were subject to formal administration, and civic accounts were neglected. Thus embezzlement and fraud became common, and the patrician class, bound by family ties, became wealthier and more powerful.

Burghers

The town patricians were increasingly criticized by the growing burgher class, which consisted of well-to-do middle-class citizens who held administrative guild positions or worked as merchants. They demanded town assemblies made up of both patricians and burghers, or at least a restriction on simony and the allocation of council seats to burghers. The burghers also opposed the clergy, whom they felt had overstepped and failed to uphold their principles. They demanded an end to the clergy's special privileges such as their exemption from taxation, as well as a reduction in their numbers. The burgher-master (guild master, or artisan) now owned both his workshop and its tools, which he allowed his apprentices to use, and provided the materials that his workers needed.[23] F. Engels cites: "To the call of Luther of rebellion against the Church, two political uprisings responded, first, the one of lower nobility, headed by Franz von Sickingen in 1523, and then, the great peasant's war, in 1525; both were crushed, because, mainly, of the indecisiveness of the party having most interest in the fight, the urban bourgeoisie". (Foreword to the English edition of: 'From Utopy Socialism to Scientific Socialism', 1892)

Plebeians

The plebeians comprised the new class of urban workers, journeymen, and peddlers. Ruined burghers also joined their ranks. Although technically potential burghers, most journeymen were barred from higher positions by the wealthy families who ran the guilds.[15] Thus their "temporary" position devoid of civic rights tended to become permanent. The plebeians did not have property like ruined burghers or peasants.

Peasants

The heavily taxed peasantry continued to occupy the lowest stratum of society. In the early 16th century, no peasant could hunt, fish, or chop wood freely, as they previously had, because the lords had recently taken control of common lands. The lord had the right to use his peasants' land as he wished; the peasant could do nothing but watch as his crops were destroyed by wild game and by nobles galloping across his fields in the course of chivalric hunts. When a peasant wished to marry, he not only needed the lord's permission but had to pay a tax. When the peasant died, the lord was entitled to his best cattle, his best garments and his best tools. The justice system, operated by the clergy or wealthy burgher and patrician jurists, gave the peasant no redress. Generations of traditional servitude and the autonomous nature of the provinces limited peasant insurrections to local areas.

Military organizations

Army of the Swabian League

The Swabian League fielded an army commanded by Georg, Truchsess von Waldburg, later known as "Bauernjörg" for his role in the suppression of the revolt.[24] He was also known as the "Scourge of the Peasants".[lower-alpha 1] The league headquarters was in Ulm, and command was exercised through a war council which decided the troop contingents to be levied from each member. Depending on their capability, members contributed a specific number of mounted knights and foot soldiers, called a contingent, to the league's army. The Bishop of Augsburg, for example, had to contribute 10 horse (mounted) and 62 foot soldiers, which would be the equivalent of a half-company. At the beginning of the revolt the league members had trouble recruiting soldiers from among their own populations (particularly among peasant class) due to fear of them joining the rebels. As the rebellion expanded many nobles had trouble sending troops to the league armies because they had to combat rebel groups in their own lands. Another common problem regarding raising armies was that while nobles were obligated to provide troops to a member of the league, they also had other obligations to other lords. These conditions created problems and confusion for the nobles as they tried to gather together forces large enough to put down the revolts.[25]

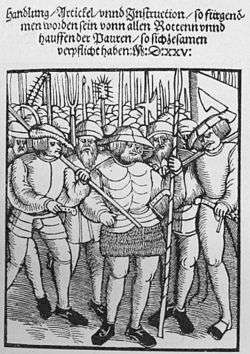

Foot soldiers were drawn from the ranks of the landsknechte. These were mercenaries, usually paid a monthly wage of four guilders, and organized into regiments (haufen) and companies (fähnlein or little flag) of 120–300 men, which distinguished it from others. Each company, in turn, was composed of smaller units of 10 to 12 men, known as rotte. The landsknechte clothed, armed and fed themselves, and were accompanied by a sizable train of sutlers, bakers, washerwomen, prostitutes and sundry individuals with occupations needed to sustain the force. Trains (tross) were sometimes larger than the fighting force, but they required organization and discipline. Each landsknecht maintained its own structure, called the gemein, or community assembly, which was symbolized by a ring. The gemein had its own leader (schultheiss), and a provost officer who policed the ranks and maintained order.[24] The use of the landsknechte in the German Peasants' War reflects a period of change between traditional noble roles or responsibilities towards warfare and practice of buying mercenary armies, which became the norm throughout the 16th century.[26]

The league relied on the armored cavalry of the nobility for the bulk of its strength; the league had both heavy cavalry and light cavalry, (rennfahne), which served as a vanguard. Typically, the rehnnfahne were the second and third sons of poor knights, the lower and sometimes impoverished nobility with small land-holdings, or, in the case of second and third sons, no inheritance or social role. These men could often be found roaming the countryside looking for work or engaging in highway robbery.[27]

To be effective the cavalry needed to be mobile, and to avoid hostile forces armed with pikes.

Peasant armies

The peasant armies were organized in bands (German: haufen), similar to the landsknecht. Each haufen was organized into unterhaufen, or fähnlein and rotten. The bands varied in size, depending on the number of insurgents available in the locality. Peasant haufen divided along territorial lines, whereas those of the landsknecht drew men from a variety of territories. Some bands could number about 4,000; others, such as the peasant force at Frankenhausen, could gather 8,000. The Alsatian peasants who took to the field at the Battle of Zabern (now Saverne) numbered 18,000.[28]

Haufen were formed from companies, typically 500 men per company, subdivided into platoons of 10 to 15 peasants each. Like the landsknechts, the peasant bands used similar titles: Oberster feldhauptmann, or supreme commander, similar to a colonel, and lieutenants, or leutinger. Each company was commanded by a captain and had its own fähnrich, or ensign, who carried the company's standard (its ensign). The companies also had a sergeant or feldweibel, and squadron leaders called rottmeister, or masters of the rotte. Officers were usually elected, particularly the supreme commander and the leutinger.[28]

The peasant army was governed by a so-called ring, in which peasants gathered in a circle to debate tactics, troop movements, alliances, and the distribution of spoils. The ring was the decision-making body. In addition to this democratic construct, each band had a hierarchy of leaders including a supreme commander and a marshal (schultheiss), who maintained law and order. Other roles included lieutenants, captains, standard-bearers, master gunner, wagon-fort master, train master, four watch-masters, four sergeant-majors to arrange the order of battle, a weibel (sergeant) for each company, two quartermasters, farriers, quartermasters for the horses, a communications officer and a pillage master.[29]

Peasant resources

The peasants possessed an important resource, the skills to build and maintain field works. They used the wagon fort effectively, a tactic that had been mastered in the Hussite Wars of the previous century.[30] Wagons were chained together in a suitable defensive location, with cavalry and draft animals placed in the center. Peasants dug ditches around the outer edge of the fort and used timber to close gaps between and underneath the wagons. In the Hussite Wars, artillery was usually placed in the center on raised mounds of earth that allowed them to fire over the wagons. Wagon forts could be erected and dismantled quickly. They were quite mobile, but they also had drawbacks: they required a fairly large area of flat terrain and they were not ideal for offense. Since their earlier use, artillery had increased in range and power.[31]

Peasants served in rotation, sometimes for one week in four, and returned to their villages after service. While the men served, others absorbed their workload. This sometimes meant producing supplies for their opponents, such as in the Archbishopric of Salzburg, where men worked to extract silver, which was used to hire fresh contingents of landsknechts for the Swabian League.[29]

However, the peasants lacked the Swabian League's cavalry, having few horses and little armour. They seem to have used their mounted men for reconnaissance. The lack of cavalry with which to protect their flanks, and with which to penetrate massed landsknecht squares, proved to be a long-term tactical and strategic problem.[32]

Causes

Historians disagree on the nature of the revolt and its causes, whether it grew out of the emerging religious controversy centered on Luther; whether a wealthy tier of peasants saw their own wealth and rights slipping away, and sought to weave them into the legal, social and religious fabric of society; or whether peasants objected to the emergence of a modernizing, centralizing nation state.

Threat to prosperity

One view is that the origins of the German Peasants' War lay partly in the unusual power dynamic caused by the agricultural and economic dynamism of the previous decades. Labor shortages in the last half of the 14th century had allowed peasants to sell their labor for a higher price; food and goods shortages had allowed them to sell their products for a higher price as well. Consequently, some peasants, particularly those who had limited allodial requirements, were able to accrue significant economic, social, and legal advantages.[33] Peasants were more concerned to protect the social, economic and legal gains they had made than about seeking further gains.[34]

Serfdom

Their attempt to break new ground was primarily seeking to increase their liberty by changing their status from serfs,[35] such as the infamous moment when the peasants of Mühlhausen refused to collect snail shells around which their lady could wind her thread. The renewal of the signeurial system had weakened in the previous half century, and peasants were unwilling to see it restored.[36]

Luther's Reformation

People in all layers of the social hierarchy—serfs or city dwellers, guildsmen or farmers, knights and aristocrats—started to question the established hierarchy. The so-called Book of One Hundred Chapters, for example, written between 1501 and 1513, promoted religious and economic freedom, attacking the governing establishment and displaying pride in the virtuous peasant.[37] The Bundschuh revolts of the first 20 years of the century offered another avenue for the expression of anti-authoritarian ideas, and for the spread of these ideas from one geographic region to another.

Luther's revolution may have added intensity to these movements, but did not create them; the two events, Luther's Protestant Reformation and the German Peasants' War, were separate, sharing the same years but occurring independently.[38] However, Luther's doctrine of the "priesthood of all believers" could be interpreted as proposing greater social equality than Luther intended. Luther vehemently opposed the revolts, writing the pamphlet Against the Murderous, Thieving Hordes of Peasants, in which he remarks "Let everyone who can, smite, slay, and stab, secretly or openly ... nothing can be more poisonous, hurtful, or devilish than a rebel. It is just as one must kill a mad dog; if you do not strike him he will strike you."

Historian Roland Bainton saw the revolt as a struggle that began as an upheaval immersed in the rhetoric of Luther's Protestant Reformation against the Catholic Church but which really was impelled far beyond the narrow religious confines by the underlying economic tensions of the time.[39][40]

Class struggle

Friedrich Engels interpreted the war as a case in which an emerging proletariat (the urban class) failed to assert a sense of its own autonomy in the face of princely power and left the rural classes to their fate.[41]

Outbreak in the southwest

During the 1524 harvest, in Stühlingen, south of the Black Forest, the Countess of Lupfen ordered serfs to collect snail shells for use as thread spools after a series of difficult harvests. Within days, 1,200 peasants had gathered, created a list of grievances, elected officers, and raised a banner.[42] Within a few weeks most of southwestern Germany was in open revolt.[42] The uprising stretched from the Black Forest, along the Rhine river, to Lake Constance, into the Swabian highlands, along the upper Danube river, and into Bavaria[43] and the Tyrol.[44]

Insurgency expands

On 16 February 1525, 25 villages belonging to the city of Memmingen rebelled, demanding of the magistrates (city council) improvements in their economic condition and the general political situation. They complained of peonage, land use, easements on the woods and the commons, as well as ecclesiastical requirements of service and payment.

The city set up a committee of villagers to discuss their issues, expecting to see a checklist of specific and trivial demands. Unexpectedly, the peasants delivered a uniform declaration that struck at the pillars of the peasant-magisterial relationship. Twelve articles clearly and consistently outlined their grievances. The council rejected many of the demands. Historians have generally concluded that the articles of Memmingen became the basis for the Twelve Articles agreed on by the Upper Swabian Peasants Confederation of 20 March 1525.

A single Swabian contingent, close to 200 horse and 1,000-foot soldiers, however, could not deal with the size of the disturbance. By 1525, the uprisings in the Black Forest, the Breisgau, Hegau, Sundgau, and Alsace alone required a substantial muster of 3,000-foot and 300 horse soldiers.[24]

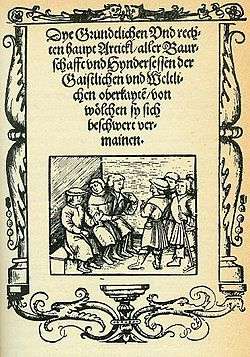

Twelve Articles (statement of principles)

On 6 March 1525, some 50 representatives of the Upper Swabian Peasants Haufen (troops)—the Baltringer Haufen, the Allgäuer Haufen, and the Lake Constance Haufen (Seehaufen)—met in Memmingen to agree to a common cause against the Swabian League.[45] One day later, after difficult negotiations, they proclaimed the establishment of the Christian Association, an Upper Swabian Peasants' Confederation.[46] The peasants met again on 15 and 20 March in Memmingen and, after some additional deliberation, adopted the Twelve Articles and the Federal Order (Bundesordnung).[46] Their banner, the Bundschuh, or a laced boot, served as the emblem of their agreement.[46] The Twelve Articles were printed over 25,000 times in the next two months, and quickly spread throughout Germany, an example of how modernization came to the aid of the rebels.[46]

The Twelve Articles demanded the right for communities to elect and depose clergymen and demanded the utilization of the "great tithe" for public purposes after subtraction of a reasonable pastor's salary.[47] (The "great tithe" was assessed by the Catholic Church against the peasant's wheat crop and the peasant's vine crops. The great tithe often amounted to more than 10% of the peasant's income.[48]) The Twelve Articles also demanded the abolition of the "small tithe" which was assessed against the peasant's other crops. Other demands of the Twelve Articles included the abolition of serfdom, death tolls, and the exclusion from fishing and hunting rights; restoration of the forests, pastures, and privileges withdrawn from the community and individual peasants by the nobility; and a restriction on excessive statute labor, taxes and rents. Finally, the Twelve Articles demanded an end to arbitrary justice and administration.[47]

Course of the war

Kempten Insurrection

Kempten im Allgäu was an important city in the Allgäu, a region in what became Bavaria, near the borders with Württemberg and Austria. In the early eighth century, Celtic monks established a monastery there, Kempten Abbey. In 1213, Holy Roman Emperor Frederick II declared the abbots members of the Reichsstand, or imperial estate, and granted the abbot the title of duke. In 1289, King Rudolf of Habsburg granted special privileges to the urban settlement in the river valley, making it a free imperial city. In 1525 the last property rights of the abbots in the Imperial City were sold in the so-called "Great Purchase", marking the start of the co-existence of two independent cities bearing the same name next to each other. In this multi-layered authority, during the Peasants' War, the abbey-peasants revolted, plundering the abbey and moving on the town.[lower-alpha 2]

Battle of Leipheim

On 4 April 1525, 5,000 peasants, the Leipheimer Haufen (literally: the Leipheim Bunch), gathered near Leipheim to rise against the city of Ulm. A band of five companies, plus approximately 25 citizens of Leipheim, assumed positions west of the town. League reconnaissance reported to the Truchsess that the peasants were well-armed. They had cannons with powder and shot and they numbered 3,000–4,000. They took an advantageous position on the east bank of the Biber. On the left stood a wood, and on their right, a stream and marshland; behind them, they had erected a wagon fortress, and they were armed with arquebuses and some light artillery pieces.[49]

As he had done in earlier encounters with the peasants, the Truchsess negotiated while he continued to move his troops into advantageous positions. Keeping the bulk of his army facing Leipheim, he dispatched detachments of horse from Hesse and Ulm across the Danube to Elchingen. The detached troops encountered a separate group of 1,200 peasants engaged in local requisitions, and entered into combat, dispersing them and taking 250 prisoners. At the same time, the Truchsess broke off his negotiations, and received a volley of fire from the main group of peasants. He dispatched a guard of light horse and a small group of foot soldiers against the fortified peasant position. This was followed by his main force; when the peasants saw the size of his main force—his entire force was 1,500 horse, 7,000-foot, and 18 field guns—they began an orderly retreat. Of the 4,000 or so peasants who had manned the fortified position, 2,000 were able to reach the town of Leipheim itself, taking their wounded with them in carts. Others sought to escape across the Danube, and 400 drowned there. The Truchsess' horse units cut down an additional 500. This was the first important battle of the war.[lower-alpha 3]

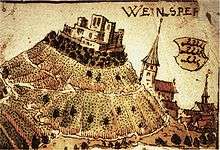

Weinsberg Massacre

An element of the conflict drew on resentment toward some of the nobility. The peasants of Odenwald had already taken the Cistercian Monastery at Schöntal, and were joined by peasant bands from Limpurg (near Schwäbisch Hall) and Hohenlohe. A large band of peasants from the Neckar valley, under the leadership of Jakob Rohrbach, joined them and from Neckarsulm, this expanded band, called the "Bright Band" (in German, Heller Haufen), marched to the town of Weinsberg, where the Count of Helfenstein, then the Austrian Governor of Württemberg, was present.[lower-alpha 4] Here, the peasants achieved a major victory. The peasants assaulted and captured the castle of Weinsberg; most of its own soldiers were on duty in Italy, and it had little protection. Having taken the count as their prisoner, the peasants took their revenge a step further: They forced him, and approximately 70 other nobles who had taken refuge with him, to run the gauntlet of pikes, a popular form of execution among the landsknechts. Rohrbach ordered the band's piper to play during the running of the gauntlet. [50][51]

This was too much for many of the peasant leaders of other bands; they repudiated Rohrbach's actions. He was deposed and replaced by a knight, Götz von Berlichingen, who was subsequently elected as supreme commander of the band. At the end of April, the band marched to Amorbach, joined on the way by some radical Odenwald peasants out for Berlichingen's blood. Berlichingen had been involved in the suppression of the Poor Conrad uprising 10 years earlier, and these peasants sought vengeance. In the course of their march, they burned down the Wildenburg castle, a contravention of the Articles of War to which the band had agreed.[52]

The massacre at Weinsberg was also too much for Luther; this is the deed that drew his ire in Against the Murderous, Thieving Hordes of Peasants in which he castigated peasants for unspeakable crimes, not only for the murder of the nobles at Weinsberg, but also for the impertinence of their revolt.[53]

Massacre at Frankenhausen

On 29 April the peasant protests in Thuringia culminated in open revolt. Large sections of the town populations joined the uprising. Together they marched around the countryside and stormed the castle of the Counts of Schwarzburg. In the following days, a larger number of insurgents gathered in the fields around the town. When Müntzer arrived with 300 fighters from Mühlhausen on 11 May, several thousand more peasants of the surrounding estates camped on the fields and pastures: the final strength of the peasant and town force was estimated at 6,000. The Landgrave, Philip of Hesse and Duke George of Saxony were on Müntzer's trail and directed their Landsknecht troops toward Frankenhausen. On 15 May joint troops of Landgraf Philipp I of Hesse and George, Duke of Saxony defeated the peasants under Müntzer near Frankenhausen in the County of Schwarzburg. [54]

The Princes' troops included close to 6,000 mercenaries, the Landsknechte. As such they were experienced, well-equipped, well-trained and of good morale. The peasants, on the other hand, had poor, if any, equipment, and many had neither experience nor training. Many of the peasants disagreed over whether to fight or negotiate. On 14 May, they warded off smaller feints of the Hesse and Brunswick troops, but failed to reap the benefits from their success. Instead the insurgents arranged a ceasefire and withdrew into a wagon fort.

The next day Philip's troops united with the Saxon army of Duke George and immediately broke the truce, starting a heavy combined infantry, cavalry and artillery attack. The peasants were caught off-guard and fled in panic to the town, followed and continuously attacked by the public forces. Most of the insurgents were slain in what turned out to be a massacre. Casualty figures are unreliable but estimates range from 3,000 to 10,000 while the Landsknecht casualties were as few as six (two of whom were only wounded). Müntzer was captured, tortured and executed at Mühlhausen on 27 May.

Battle of Böblingen

The Battle of Böblingen (12 May 1525) perhaps resulted in the greatest casualties of the war. When the peasants learned that the Truchsess (Seneschal) of Waldburg had pitched camp at Rottenburg, they marched towards him and took the city of Herrenberg on 10 May. Avoiding the advances of the Swabian League to retake Herrenberg, the Württemberg band set up three camps between Böblingen and Sindelfingen. There they formed four units, standing upon the slopes between the cities. Their 18 artillery pieces stood on a hill called Galgenberg, facing the hostile armies. The peasants were overtaken by the League's horse, which encircled and pursued them for kilometres.[55] While the Württemberg band lost approximately 3,000 peasants (estimates range from 2,000 to 9,000), the League lost no more than 40 soldiers.[56]

Battle of Königshofen

At Königshofen, on 2 June, peasant commanders Wendel Hipfler and Georg Metzler had set camp outside of town. Upon identifying two squadrons of League and Alliance horse approaching on each flank, now recognized as a dangerous Truchsess strategy, they redeployed the wagon-fort and guns to the hill above the town. Having learned how to protect themselves from a mounted assault, peasants assembled in four massed ranks behind their cannon, but in front of their wagon-fort, intended to protect them from a rear attack. The peasant gunnery fired a salvo at the League advanced horse, which attacked them on the left. The Truchsess' infantry made a frontal assault, but without waiting for his foot soldiers to engage, he also ordered an attack on the peasants from the rear. As the knights hit the rear ranks, panic erupted among the peasants. Hipler and Metzler fled with the master gunners. Two thousand reached the nearby woods, where they re-assembled and mounted some resistance. In the chaos that followed, the peasants and the mounted knights and infantry conducted a pitched battle. By nightfall only 600 peasants remained. The Truchsess ordered his army to search the battlefield, and the soldiers discovered approximately 500 peasants who had feigned death. The battle is also called the Battle of the Turmberg, for a watch-tower on the field.[57]

Siege of Freiburg im Breisgau

Freiburg, which was a Habsburg territory, had considerable trouble raising enough conscripts to fight the peasants, and when the city did manage to put a column together and march out to meet them, the peasants simply melted into the forest. After the refusal by the Duke of Baden, Margrave Ernst, to accept the 12 Articles, peasants attacked abbeys in the Black Forest. The Knights Hospitallers at Heitersheim fell to them on 2 May; Haufen to the north also sacked abbeys at Tennenbach and Ettenheimmünster. In early May, Hans Müller arrived with over 8,000 men at Kirzenach, near Freiburg. Several other bands arrived, bringing the total to 18,000, and within a matter of days, the city was encircled and the peasants made plans to lay a siege.[58]

Second Battle of Würzburg (1525)

After the peasants took control of Freiburg in Breisgau, Hans Müller took some of the group to assist in the siege at Radolfzell. The rest of the peasants returned to their farms. On 4 June, near Würzburg, Müller and his small group of peasant-soldiers joined with the Franconian farmers of the Hellen Lichten Haufen. Despite this union, the strength of their force was relatively small. At Waldburg-Zeil near Würzburg they met the army of Götz von Berlichingen ("Götz of the Iron Hand"). An imperial knight and experienced soldier, although he had a relatively small force himself, he easily defeated the peasants. In approximately two hours, more than 8,000 peasants were killed.

Closing stages

Several smaller uprisings were also put down. For example, on 23/24 June 1525 in the Battle of Pfeddersheim the rebellious haufens in the Palatine Peasants' War were decisively defeated. By September 1525 all fighting and punitive action had ended. Emperor Charles V and Pope Clemens VII thanked the Swabian League for its intervention.

Ultimate failure of the rebellion

The peasant movement ultimately failed, with cities and nobles making a separate peace with the princely armies that restored the old order in a frequently harsher form, under the nominal control of the Holy Roman Emperor Charles V, represented in German affairs by his younger brother Ferdinand. The main causes of the failure of the rebellion was the lack of communication between the peasant bands because of territorial divisions, and because of their military inferiority.[59] While Landsknechts, professional soldiers and knights joined the peasants in their efforts (albeit in fewer numbers), the Swabian League had a better grasp of military technology, strategy and experience.

The aftermath of the German Peasants' War led to an overall reduction of rights and freedoms of the peasant class, effectively pushing them out of political life. Certain territories in upper Swabia such as Kempton, Weissenau, and Tyrol saw peasants create territorial assemblies (Landschaft), sit on territorial committees as well as other bodies which dealt with issues that directly affected the peasants like taxation.[59] However the overall goals of change for these peasants, particularly looking through the lens of the Twelve Articles, had failed to come to pass and would remain stagnant, real change coming centuries later.

Historiography

Marx and Engels

Friedrich Engels wrote The Peasant War in Germany (1850), which opened up the issue of the early stages of German capitalism on later bourgeois "civil society" at the level of peasant economies. Engels' analysis was picked up in the middle 20th century by the French Annales School, and Marxist historians in East Germany and Britain.[60] Using Karl Marx's concept of historical materialism, Engels portrayed the events of 1524–1525 as prefiguring the 1848 Revolution. He wrote, "Three centuries have passed and many a thing has changed; still the Peasant War is not so impossibly far removed from our present struggle, and the opponents who have to be fought are essentially the same. We shall see the classes and fractions of classes which everywhere betrayed 1848 and 1849 in the role of traitors, though on a lower level of development, already in 1525."[61] Engels ascribed the failure of the revolt to its fundamental conservatism.[62] This led both Marx and Engels to conclude that the communist revolution, when it occurred, would be led not by a peasant army but by an urban proletariat.

Later historiography

_1989%2C_MiNr_Block_097.jpg)

Historians disagree on the nature of the revolt and its causes, whether it grew out of the emerging religious controversy centered on Martin Luther; whether a wealthy tier of peasants saw their wealth and rights slipping away, and sought to re-inscribe them in the fabric of society; or whether it was peasant resistance to the emergence of a modernizing, centralizing political state. Historians have tended to categorize it either as an expression of economic problems, or as a theological/political statement against the constraints of feudal society.[63]

After the 1930s, Günter Franz's work on the peasant war dominated interpretations of the uprising. Franz understood the Peasants' War as a political struggle in which social and economic aspects played a minor role. Key to Franz's interpretation is the understanding that peasants had benefited from the economic recovery of the early 16th century and that their grievances, as expressed in such documents as the Twelve Articles, had little or no economic basis. He interpreted the uprising's causes as essentially political, and secondarily economic: the assertions by princely landlords of control over the peasantry through new taxes and the modification of old ones, and the creation of servitude backed up by princely law. For Franz, the defeat thrust the peasants from view for centuries.[64]

The national aspect of the Peasants' Revolt was also utilised by the Nazis. For example, an SS cavalry division (the 8th SS Cavalry Division Florian Geyer) was named after Florian Geyer, a knight who led a peasant unit known as the Black Company.

A new economic interpretation arose in the 1950s and 1960s. This interpretation was informed by economic data on harvests, wages and general financial conditions. It suggested that in the late 15th and early 16th centuries, peasants saw newly achieved economic advantages slipping away, to the benefit of the landed nobility and military groups. The war was thus an effort to wrest these social, economic and political advantages back.[64]

Meanwhile, historians in East Germany engaged in major research projects to support the Marxist viewpoint.[65]

Starting in the 1970s, research benefited from the interest of social and cultural historians. Using sources such as letters, journals, religious tracts, city and town records, demographic information, family and kinship developments, historians challenged long-held assumptions about German peasants and the authoritarian tradition.

This view held that peasant resistance took two forms. The first, spontaneous (or popular) and localized revolt drew on traditional liberties and old law for its legitimacy. In this way, it could be explained as a conservative and traditional effort to recover lost ground. The second was an organized inter-regional revolt that claimed its legitimacy from divine law and found its ideological basis in the Reformation.

Later historians refuted both Franz's view of the origins of the war, and the Marxist view of the course of the war, and both views on the outcome and consequences. One of the most important was Peter Blickle's emphasis on communalism. Although Blickle sees a crisis of feudalism in the latter Middle Ages in southern Germany, he highlighted political, social and economic features that originated in efforts by peasants and their landlords to cope with long term climate, technological, labor and crop changes, particularly the extended agrarian crisis and its drawn-out recovery.[15] For Blickle, the rebellion required a parliamentary tradition in southwestern Germany and the coincidence of a group with significant political, social and economic interest in agricultural production and distribution. These individuals had a great deal to lose.[66]

This view, which asserted that the uprising grew out of the participation of agricultural groups in the economic recovery, was in turn challenged by Scribner, Stalmetz and Bernecke. They claimed that Blickle's analysis was based on a dubious form of the Malthusian principle, and that the peasant economic recovery was significantly limited, both regionally and in its depth, allowing only a few peasants to participate. Blickle and his students later modified their ideas about peasant wealth. A variety of local studies showed that participation was not as broad based as formerly thought.[67][68]

The new studies of localities and social relationships through the lens of gender and class showed that peasants were able to recover, or even in some cases expand, many of their rights and traditional liberties, to negotiate these in writing, and force their lords to guarantee them.[69]

The course of the war also demonstrated the importance of a congruence of events: the new liberation ideology, the appearance within peasant ranks of charismatic and military-trained men like Müntzer and Gaismair, a set of grievances with specific economic and social origins, a challenged set of political relationships and a communal tradition of political and social discourse.

See also

- List of peasant revolts

- Popular revolt in late-medieval Europe

- Melchior Rink, who was accused by Lutherans of being an instigator of the war

Notes

- Born in Waldsee (25 January 1488 – 29 May 1531), the son of Johann II von Waldburg-Wolfegg († 19. October 1511) and of Helena von Hohenzollern, he married Appolonia von Waldburg-Sonnenberg in 1509; and, secondly, Maria von Oettingen (11 April 1498 – 18 August 1555). Marek, Miroslav. "Waldburg genealogical table". Genealogy.EU.)

- More conflict arose after the Imperial City converted to Protestantism in direct opposition to the Catholic monastery (and Free City) in 1527.

- In 1994, a mass grave was discovered near Leipheim; linked by coins to the time period, archaeologists discovered that most of the occupants had died of head wounds (Miller 2003, p. 21).

- The count, much despised by his subjects, was the son-in-law of the previous Holy Roman Emperor, Maximilian.(Miller 2003, p. 35)

References

- Blickle 1981, p. 165.

- Klassen 1979, p. 59.

- Jaroslav J. Pelikan, Hilton C. Oswald, Luther's Works, 55 vols. (St. Louis and Philadelphia: Concordia Pub. House and Fortress Press, 1955–1986), 46: 50–51.

- Bainton 1978, p. 76.

- Wolf 1962, p. 47.

- "Martin Luther and the Peasants' War".

- Luther. Open Letter on the Harsh Book. (1525).

- Donald K. McKim (2003). The Cambridge Companion to Martin Luther. Cambridge University Press. pp. 184–6. ISBN 9780521016735.

- Scott 1989, p. 132ff.

- Scott 1989, p. 164ff.

- Scott 1989, p. 183.

- Wolf 1962, p. 147.

- Engels 1978, p. 402.

- Klassen 1979, p. 57.

- Engels 1978, pp. 400.

- Engels 1978, pp. 403–404.

- Engels 1978, p. 687, Note 295.

- Lins 1908, Cologne.

-

- (in German) Ennen, pp. 291–313.

- Engels 1978, p. 404.

- Engels 1978, p. 405.

- Engels 1978, pp. 407.

- Miller 2003, p. 7.

- Sea, Thomas F. (2007). "The German Princes' Response to the German Peasants' Revolt of 1525". Central European History. 40 (2): 219–240. doi:10.1017/S0008938907000520. JSTOR 20457227.

- Moxey, Keith (1989). Peasants Warriors and Wives. London: The University of Chicago Press. p. 71. ISBN 978-0-226-54391-8.

- Miller 2003, p. 6.

- Miller 2003, p. 8.

- Miller 2003, p. 10.

- Wilhelm 1907, Hussites.

- Miller 2003, p. 13.

- Miller 2003, p. 11.

- Zagorín 1984, pp. 187–188.

- Zagorín 1984, p. 187.

- Zagorín 1984, p. 188.

- Bercé 1987, p. 154.

- Strauss 1971, p. .

- Zagorín 1984, p. 190.

- Bainton 1978, p. 208.

- Engels 1978, pp. 411–412 & 446.

- Engels 1978, pp. 59–62.

- Engels 1978, p. 446.

- Miller 2003, p. 4.

- Hannes Obermair, "Logiche sociali della rivolta tradizionalista. Bolzano e l’impatto della "Guerra dei contadini" del 1515," Studi Trentini. Storia, 92#1 (2013), pp. 185–194.

- Bainton 1978, p. 210.

- Bainton 1978, p. 211-212.

- Engels 1978, p. 451.

- Engels 1978, p. 691, Note 331.

- Miller 2003, pp. 20–21.

- Menzel 1848–49, p. 239.

- Miller2003, p. 35.

- Miller 2003, p. 34.

- Blickle 1981, p. xxiii.

- Scott 1989, p. 158ff.

- Miller 2003, p. 33.

- Wald 2010, Böblingen.

- Miller 2003, p. 37.

- Scott, pp. 204–209.

- Blickle, Peter (1981). the revolution of 1525: the German Peasants' War from a new perspective. Baltimore and London: The Johns Hopkins University Press. pp. 181–182. ISBN 978-0-8018-2472-2.

- Eric R. Wolf, "The Peasant War in Germany: Friedrich Engels as Social Historian," Science and Society (1987) 51:1 pp82-92.

- Engels 1978, p. 399.

- Engels 1978, pp. 397,482.

- Ozment 1980, p. 279.

- Ozment 1980, p. 250.

- Tom Scott, "The Peasants' War: A Historiographical Review," Historical Journal (1979) 22#3, pp. 693-720 in JSTOR

- Peter Blickle, The Revolution of 1525: The German Peasants War from a New Perspective (1981).

- Tom Scott and Robert W. Scribner, eds. The German peasants' war: a history in documents (Humanities Press International, 1991).

- Govind P. Sreenivasan, "The social origins of the Peasants' War of 1525 in Upper Swabia." Past & Present 171 (2001): 30-65. in JSTOR

- Keith Moxey, Peasants, Warriors, and Wives: Popular Imagery in the Reformation (U of Chicago Press, 2004).

Further reading

- Bainton, Roland H. (1978). Here I Stand: A Life of Martin Luther. Nashville: Pierce & Smith Company. pp. 76, 202, 214–221.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Bercé, Yves-Marie (1987). Revolt and revolution in early modern Europe: an essay on the history of political violence. Translated by Bergin, Joseph. Manchester: Manchester University Press. p. 154. ISBN 9780719019678.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Blickle, Peter (1981). The Revolution of 1525: The German Peasants War from a New Perspective. Translated by Brady, Thomas A., Jr; Midelfort, H. C. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Bok, Janos. The German Peasant War of 1525 (The Library of Peasant Studies : No. 3) (1976) excerpt and text search

- Engels, Friedrich (1978) [1850]. "The Peasant War in Germany". Marx & Engels Collected Works. 10. New York: International Publishers. pp. 59–62, 402–405, 451, 691.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link) (web source (1850 edition))

- Klassen, Peter J. (1979). Europe in Reformation. Englewood, Cliffs, New Jersey: Prentice-Hall. p. 57.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Lins, J. (1908). . In Herbermann, Charles (ed.). Catholic Encyclopedia. 4. New York: Robert Appleton Company.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Lucas, Henry S. (1960). The Renaissance and the Reformation. New York: Harper & Row. p. 448.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Menzel, Wolfgang (1848–49). The history of Germany, from the earliest period to the present time. Translated by Horrocks, Mrs. George. London: H. G. Bohn. p. 239.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link), Volume One, Volume Two, Volume Three

- Miller, Douglas (2003). Armies of the German Peasants' War 1524–1526. Oxford: Osprey Publishing. pp. 4, 6–8, 10, 11, 13, 20, 21, 33–35.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Ozment, Steven (1980). The age of reform 1250–1550: an intellectual and religious history of late medieval and reformation Europe. New Haven: Yale University Press. ISBN 978-0-300-02760-0.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Pollock, James K.; Thomas, Homer (1952). Germany in Power and Eclipse. London: D. Van Nostrand. p. 483.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Scott, Tom (1986). Freiburg and the Breisgau: Town-Country Relations in the Age of Reformation and Peasants' War. Oxford: Clarendon Press. ISBN 9780198219965.

- Scott, Tom (1989). Thomas Müntzer: Theology and Revolution in the German Reformation. London: Macmillan. ISBN 978-0-33346-498-4.

- Strauss, Gerald, ed. (1971). Manifestations of Discontent in Germany on the Eve of the Reformation. Bloomington, Illinois: University of Illinois Press.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Wolf, John B. (1962). The Emergence of European Civilization. New York: Harper & Row. pp. 47, 147.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Zagorín, Pérez (1984). Rebels and rulers, 1500–1660. Cambridge and New York: Cambridge University Press. pp. 187, 188, 190. ISBN 978-0-521-28711-1.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Wilhelm, Joseph (1907). . In Herbermann, Charles (ed.). Catholic Encyclopedia. 2. New York: Robert Appleton Company.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

External links

- Wald, Annerose (30 June 2010). "Peasants' War museum Böblingen" (in German). Peasants' War museum.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

Further reading

| Wikisource has the text of the 1879 American Cyclopædia article Peasants' War. |

| Wikisource has the text of the 1913 Catholic Encyclopedia article War of the Peasants (1524-25). |

| Wikisource has the text of the 1905 New International Encyclopedia article Peasant War. |

- Dixon, C. Scott (1997). "Case-study 3: The Peasant Reformation in Germany: Bibliography". Staffordshire, UK: Keele University. Retrieved 21 August 2012. Cite journal requires

|journal=(help) - Linebaugh, Peter (March 2015). "Fire Next Time - The Rainbow Sign". CounterPunch.