Anabaptism

Anabaptism (from Neo-Latin anabaptista,[1] from the Greek ἀναβαπτισμός: ἀνά- "re-" and βαπτισμός "baptism",[2] German: Täufer, earlier also Wiedertäufer[lower-alpha 1]) is a Christian movement which traces its origins to the Radical Reformation. The movement is generally seen as an offshoot of Protestantism, although this view has been challenged by some Anabaptists.[3][4][5]

| Part of a series on |

| Anabaptism |

|---|

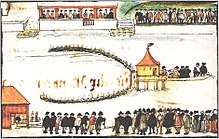

Dirk Willems (picture) saves his pursuer. This act of mercy led to his recapture, after which he was burned at the stake near Asperen (etching from Jan Luyken in the 1685 edition of Martyrs Mirror) |

|

Background |

|

Distinctive doctrines |

|

Largest groups |

|

Related movements |

|

|

| Part of a series on |

| Protestantism |

|---|

|

|

Major branches |

|

Minor branches |

|

Broad-based movements |

|

Related movements |

|

|

Approximately 4 million Anabaptists live in the world today with adherents scattered across all inhabited continents. In addition to a number of minor Anabaptist groups, the most numerous include the Mennonites at 2.1 million, the German Baptists at 1.5 million, the Amish at 300,000 and the Hutterites at 50,000.

In the 21st century there are large cultural differences between assimilated Anabaptists, who do not differ much from evangelicals or mainline Protestants, and traditional groups like the Amish, the Old Colony Mennonites, the Old Order Mennonites, the Hutterites and the Old German Baptist Brethren.

The early Anabaptists formulated their beliefs in the Schleitheim Confession, in 1527.[6][7] Anabaptists believe that baptism is valid only when candidates confess their faith in Christ and want to be baptized. This believer's baptism is opposed to baptism of infants, who are not able to make a conscious decision to be baptized. Anabaptists are those who are in a traditional line with the early Anabaptists of the 16th century. Other Christian groups with different roots also practice believer's baptism, such as Baptists, but these groups are not seen as Anabaptist. The Amish, Hutterites, and Mennonites are direct descendants of the early Anabaptist movement. Schwarzenau Brethren, Bruderhof, and the Apostolic Christian Church are considered later developments among the Anabaptists.

The name Anabaptist means "one who baptizes again". Their persecutors named them this, referring to the practice of baptizing persons when they converted or declared their faith in Christ, even if they had been baptized as infants.[8] Anabaptists required that baptismal candidates be able to make a confession of faith that is freely chosen and so rejected baptism of infants. The early members of this movement did not accept the name Anabaptist, claiming that infant baptism was not part of scripture and was therefore null and void. They said that baptizing self-confessed believers was their first true baptism:

I have never taught Anabaptism.... But the right baptism of Christ, which is preceded by teaching and oral confession of faith, I teach, and say that infant baptism is a robbery of the right baptism of Christ.

Anabaptists were heavily and long persecuted starting in the 16th century by both Magisterial Protestants and Roman Catholics, largely because of their interpretation of scripture which put them at odds with official state church interpretations and with government. Anabaptism was never established by any state and therefore never enjoyed any associated privileges. Most Anabaptists adhered to a literal interpretation of the Sermon on the Mount which precluded taking oaths, participating in military actions, and participating in civil government. Some groups who practiced rebaptism, now extinct, believed otherwise and complied with these requirements of civil society.[lower-alpha 2] They were thus technically Anabaptists, even though conservative Amish, Mennonites, Hutterites, and some historians consider them outside true Anabaptism. Conrad Grebel wrote in a letter to Thomas Müntzer in 1524:

True Christian believers are sheep among wolves, sheep for the slaughter... Neither do they use worldly sword or war, since all killing has ceased with them.[10]

Origins

- (Not shown are non-Nicene, nontrinitarian, and some restorationist denominations.)

Medieval forerunners

Anabaptists are considered to have begun with the Radical Reformers in the 16th century, but historians classify certain people and groups as their forerunners because of a similar approach to the interpretation and application of the Bible. For instance, Petr Chelčický, a 15th-century Bohemian reformer, taught most of the beliefs considered integral to Anabaptist theology.[11] Medieval antecedents may include the Brethren of the Common Life, the Hussites, Dutch Sacramentists,[12][13] and some forms of monasticism. The Waldensians also represent a faith similar to the Anabaptists.[14]

Medieval dissenters and Anabaptists who held to a literal interpretation of the Sermon on the Mount share in common the following affirmations:

- The believer must not swear oaths or refer disputes between believers to law-courts for resolution, in accordance with 1 Corinthians 6:1–11.

- The believer must not bear arms or offer forcible resistance to wrongdoers, nor wield the sword. No Christian has the jus gladii (the right of the sword). Matthew 5:39

- Civil government (i.e. "Caesar") belongs to the world. The believer belongs to God's kingdom, so must not fill any office nor hold any rank under government, which is to be passively obeyed. John 18:36 Romans 13:1–7

- Sinners or unfaithful ones are to be excommunicated, and excluded from the sacraments and from intercourse with believers unless they repent, according to 1 Corinthians 5:9–13 and Matthew 18:15 seq., but no force is to be used towards them.

Zwickau prophets and the German Peasants' War

On December 27, 1521, three "prophets" appeared in Wittenberg from Zwickau who were influenced by (and, in turn, influencing) Thomas Müntzer—Thomas Dreschel, Nicholas Storch, and Mark Thomas Stübner. They preached an apocalyptic, radical alternative to Lutheranism. Their preaching helped to stir the feelings concerning the social crisis which erupted in the German Peasants' War in southern Germany in 1525 as a revolt against feudal oppression. Under the leadership of Müntzer, it became a war against all constituted authorities and an attempt to establish by revolution an ideal Christian commonwealth, with absolute equality among persons and the community of goods. The Zwickau prophets were not Anabaptists (that is, they did not practise "rebaptism"); nevertheless, the prevalent social inequities and the preaching of men such as these have been seen as laying the foundation for the Anabaptist movement. The social ideals of the Anabaptist movement coincided closely with those of leaders in the German Peasants' War. Studies have found a very low percentage of subsequent sectarians to have taken part in the peasant uprising.[15]

Views on origins

Research on the origins of the Anabaptists has been tainted both by the attempts of their enemies to slander them and by the attempts of their supporters to vindicate them. It was long popular to classify all Anabaptists as Munsterites and radicals associated with the Zwickau prophets, Jan Matthys, John of Leiden, and Thomas Müntzer. Those desiring to correct this error tended to over-correct and deny all connections between the larger Anabaptist movement and the most radical elements.

The modern era of Anabaptist historiography arose with Roman Catholic scholar Carl Adolf Cornelius' publication of Die Geschichte des Münsterischen Aufruhrs (The History of the Münster Uprising) in 1855. Baptist historian Albert Henry Newman (1852–1933), who Harold S. Bender said occupied "first position in the field of American Anabaptist historiography", made a major contribution with his A History of Anti-Pedobaptism (1897).

Three main theories on origins of the Anabaptists are the following:

- The movement began in a single expression in Zürich and spread from there (Monogenesis);

- It developed through several independent movements (polygenesis); and

- It was a continuation of true New Testament Christianity (apostolic succession or church perpetuity).

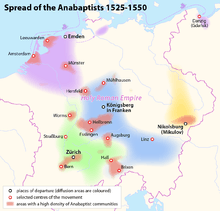

Monogenesis

A number of scholars (e.g. Harold S. Bender, William Estep, Robert Friedmann) consider the Anabaptist movement to have developed from the Swiss Brethren movement of Conrad Grebel, Felix Manz, George Blaurock, et al. They generally held that Anabaptism had its origins in Zürich, and that the Anabaptism of the Swiss Brethren was transmitted to southern Germany, Austria, the Netherlands, and northern Germany, where it developed into its various branches. The monogenesis theory usually rejects the Münsterites and other radicals from the category of true Anabaptists.[16] In the monogenesis view the time of origin is January 21, 1525, when Conrad Grebel baptized George Blaurock, and Blaurock in turn baptized several others immediately. These baptisms were the first "re-baptisms" known in the movement.[17] This continues to be the most widely accepted date posited for the establishment of Anabaptism.

Polygenesis

James M. Stayer, Werner O. Packull, and Klaus Deppermann disputed the idea of a single origin of Anabaptists in a 1975 essay entitled "From Monogenesis to Polygenesis", suggesting that February 24, 1527, at Schleitheim is the proper date of the origin of Anabaptism. On this date the Swiss Brethren wrote a declaration of belief called the Schleitheim Confession.[18] The authors of the essay noted the agreement among previous Anabaptist historians on polygenesis, even when disputing the date for a single starting point: "Hillerbrand and Bender (like Holl and Troeltsch) were in agreement that there was a single dispersion of Anabaptism ..., which certainly ran through Zurich. The only question was whether or not it went back further to Saxony."[18]:83 After criticizing the standard polygenetic history, the authors found six groups in early Anabaptism which could be collapsed into three originating "points of departure": "South German Anabaptism, the Swiss Brethren, and the Melchiorites".[19] According to their polygenesis theory, South German–Austrian Anabaptism "was a diluted form of Rhineland mysticism", Swiss Anabaptism "arose out of Reformed congregationalism", and Dutch Anabaptism was formed by "Social unrest and the apocalyptic visions of Melchior Hoffman". As examples of how the Anabaptist movement was influenced from sources other than the Swiss Brethren movement, mention has been made of how Pilgram Marpeck's Vermanung of 1542 was deeply influenced by the Bekenntnisse of 1533 by Münster theologian Bernhard Rothmann. Melchior Hoffman influenced the Hutterites when they used his commentary on the Apocalypse shortly after he wrote it.

Others who have written in support of polygenesis include Grete Mecenseffy and Walter Klaassen, who established links between Thomas Müntzer and Hans Hut. In another work, Gottfried Seebaß and Werner Packull showed the influence of Thomas Müntzer on the formation of South German Anabaptism. Similarly, author Steven Ozment linked Hans Denck and Hans Hut with Thomas Müntzer, Sebastian Franck, and others. Author Calvin Pater showed how Andreas Karlstadt influenced Swiss Anabaptism in various areas, including his view of Scripture, doctrine of the church, and views on baptism.

Several historians, including Thor Hall,[20] Kenneth Davis,[21] and Robert Kreider,[22] have also noted the influence of Humanism on Radical Reformers in the three originating points of departure to account for how this brand of reform could develop independently from each other. Relatively recent research, begun in a more advanced and deliberate manner by Andrew P. Klager, also explores how the influence and a particular reading of the Church Fathers contributed to the development of distinctly Anabaptist beliefs and practices in separate regions of Europe in the early 16th century, including by Menno Simons in the Netherlands, Conrad Grebel in Switzerland, Thomas Müntzer in central Germany, Pilgram Marpeck in the Tyrol, Peter Walpot in Moravia, and especially Balthasar Hubmaier in southern Germany, Switzerland, and Moravia.[23][24]

Apostolic succession

Baptist successionists have, at times, pointed to 16th-century Anabaptists as part of an apostolic succession of churches ("church perpetuity") from the time of Christ.[25] This view is held by some Baptists, some Mennonites, and a number of "true church" movements.[lower-alpha 3]

The opponents of the Baptist successionism theory emphasize that these non-Catholic groups clearly differed from each other, that they held some heretical views,[lower-alpha 4] or that the groups had no connection with one another and had origins that were separate both in time and in place.

A different strain of successionism is the theory that the Anabaptists are of Waldensian origin. Some hold the idea that the Waldensians are part of the apostolic succession, while others simply believe they were an independent group out of whom the Anabaptists arose. Ludwig Keller, Thomas M. Lindsay, H. C. Vedder, Delbert Grätz, John T. Christian and Thieleman J. van Braght (author of Martyrs Mirror) all held, in varying degrees, the position that the Anabaptists were of Waldensian origin.

History

(spread from Königsberg in Franken)

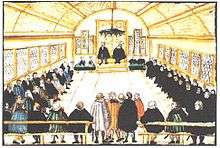

Switzerland

Anabaptism in Switzerland began as an offshoot of the church reforms instigated by Ulrich Zwingli. As early as 1522 it became evident that Zwingli was on a path of reform preaching when he began to question or criticize such Catholic practices as tithes, the mass, and even infant baptism. Zwingli had gathered a group of reform-minded men around him, with whom he studied classical literature and the scriptures. However, some of these young men began to feel that Zwingli was not moving fast enough in his reform. The division between Zwingli and his more radical disciples became apparent in an October 1523 disputation held in Zurich. When the discussion of the mass was about to be ended without making any actual change in practice, Conrad Grebel stood up and asked "what should be done about the mass?" Zwingli responded by saying the council would make that decision. At this point, Simon Stumpf, a radical priest from Höngg, answered saying, "The decision has already been made by the Spirit of God."[26]

This incident illustrated clearly that Zwingli and his more radical disciples had different expectations. To Zwingli, the reforms would only go as fast as the city Council allowed them. To the radicals, the council had no right to make that decision, but rather the Bible was the final authority of church reform. Feeling frustrated, some of them began to meet on their own for Bible study. As early as 1523, William Reublin began to preach against infant baptism in villages surrounding Zurich, encouraging parents to not baptize their children.

Seeking fellowship with other reform-minded people, the radical group wrote letters to Martin Luther, Andreas Karlstadt, and Thomas Müntzer. Felix Manz began to publish some of Karlstadt's writings in Zurich in late 1524. By this time the question of infant baptism had become agitated and the Zurich council had instructed Zwingli to meet weekly with those who rejected infant baptism "until the matter could be resolved".[27] Zwingli broke off the meetings after two sessions, and Felix Manz petitioned the Council to find a solution, since he felt Zwingli was too hard to work with. The council then called a meeting for January 17, 1525.

The Council ruled in this meeting that all who continued to refuse to baptize their infants should be expelled from Zurich if they did not have them baptized within one week. Since Conrad Grebel had refused to baptize his daughter Rachel, born on January 5, 1525, the Council decision was extremely personal to him and others who had not baptized their children. Thus, when sixteen of the radicals met on Saturday evening, January 21, 1525, the situation seemed particularly dark. The Hutterian Chronicle records the event:

After prayer, George of the House of Jacob (George Blaurock) stood up and besought Conrad Grebel for God's sake to baptize him with the true Christian baptism upon his faith and knowledge. And when he knelt down with such a request and desire, Conrad baptized him, since at that time there was no ordained minister to perform such work.[28]

Afterwards Blaurock was baptized, he in turn baptized others at the meeting. Even though some had rejected infant baptism before this date, these baptisms marked the first re-baptisms of those who had been baptized as infants and thus, technically, Swiss Anabaptism was born on that day.[29][30]

Tyrol

Anabaptism appears to have come to Tyrol through the labors of George Blaurock. Similar to the German Peasants' War, the Gaismair uprising set the stage by producing a hope for social justice. Michael Gaismair had tried to bring religious, political, and economical reform through a violent peasant uprising, but the movement was squashed.[31] Although little hard evidence exists of a direct connection between Gaismair's uprising and Tyrolian Anabaptism, at least a few of the peasants involved in the uprising later became Anabaptists. While a connection between a violent social revolution and non-resistant Anabaptism may be hard to imagine, the common link was the desire for a radical change in the prevailing social injustices. Disappointed with the failure of armed revolt, Anabaptist ideals of an alternative peaceful, just society probably resonated on the ears of the disappointed peasants.[32]

Before Anabaptism proper was introduced to South Tyrol, Protestant ideas had been propagated in the region by men such as Hans Vischer, a former Dominican. Some of those who participated in conventicles where Protestant ideas were presented later became Anabaptists. As well, the population in general seemed to have a favorable attitude towards reform, be it Protestant or Anabaptist. George Blaurock appears to have preached itinerantly in the Puster Valley region in 1527, which most likely was the first introduction of Anabaptist ideas in the area. Another visit through the area in 1529 reinforced these ideas, but he was captured and burned at the stake in Klausen on September 6, 1529.[33]

Jacob Hutter was one of the early converts in South Tyrol, and later became a leader among the Hutterites, who received their name from him. Hutter made several trips between Moravia and Tyrol, and most of the Anabaptists in South Tyrol ended up emigrating to Moravia because of the fierce persecution unleashed by Ferdinand I. In November 1535, Hutter was captured near Klausen and taken to Innsbruck where he was burned at the stake on February 25, 1536. By 1540 Anabaptism in South Tyrol was beginning to die out, largely because of the emigration to Moravia of the converts because of incessant persecution.[34]

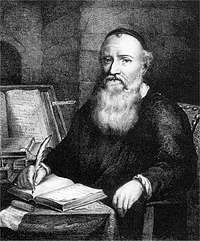

Low Countries and northern Germany

Melchior Hoffman is credited with the introduction of Anabaptist ideas into the Low Countries. Hoffman had picked up Lutheran and Reformed ideas, but on April 23, 1530 he was "re-baptized" at Strasbourg and within two months had gone to Emden and baptized about 300 persons.[35] For several years Hoffman preached in the Low Countries until he was arrested and imprisoned at Strasbourg, where he died about 10 years later. Hoffman's apocalyptic ideas were indirectly related to the Münster Rebellion, even though he was "of a different spirit".[36] Obbe and Dirk Philips had been baptized by disciples of Jan Matthijs, but were opposed to the violence that occurred at Münster.[37] Obbe later became disillusioned with Anabaptism and withdrew from the movement in about 1540, but not before ordaining David Joris, his brother Dirk, and Menno Simons, the latter from whom the Mennonites received their name.[38] David Joris and Menno Simons parted ways, with Joris placing more emphasis on "spirit and prophecy", while Menno emphasized the authority of the Bible. For the Mennonite side, the emphasis on the "inner" and "spiritual" permitted compromise to "escape persecution", while to the Joris side, the Mennonites were under the "dead letter of the Scripture".[38]

Because of persecution and expansion, some of the Low Country Mennonites emigrated to Vistula delta, a region settled by Germans but under Polish rule until it became part of Prussia in 1772. There they formed the Vistula delta Mennonites integrating some other Mennonites mainly from Northern Germany. In the late 18th century, several thousand of them migrated from there to Ukraine (which at the time was part of Russia) forming the so-called Russian Mennonites. Beginning in 1874, many of them emigrated to the prairie states and provinces of the United States and Canada. In the 1920s, the conservative faction of the Canadian settlers went to Mexico and Paraguay. Beginning in the 1950s, the most conservative of them started to migrate to Bolivia. In 1958, Mexican Mennonites migrated to Belize. Since the 1980s, traditional Russian Mennonites migrated to Argentina. Smaller groups went to Brazil and Uruguay. In 2015, some Mennonites from Bolivia settled in Peru. In 2018, there are more than 200,000 of them living in colonies in Central and South America.

Moravia, Bohemia and Silesia

Although Moravian Anabaptism was a transplant from other areas of Europe, Moravia soon became a center for the growing movement, largely because of the greater religious tolerance found there.[39][40] Hans Hut was an early evangelist in the area, with one historian crediting him with baptizing more converts in two years than all the other Anabaptist evangelists put together.[41] The coming of Balthasar Hübmaier to Nikolsburg was a definite boost for Anabaptist ideas to the area. With the great influx of religious refugees from all over Europe, many variations of Anabaptism appeared in Moravia, with Jarold Zeman documenting at least ten slightly different versions.[42] Soon, one-eyed Jacob Wiedemann appeared at Nikolsburg, and began to teach the pacifistic convictions of the Swiss Brethren, on which Hübmaier had been less authoritative. This would lead to a division between the Schwertler (sword-bearing) and the Stäbler (staff-bearing). Wiedemann and those with him also promoted the practice of community of goods. With orders from the lords of Liechtenstein to leave Nikolsburg, about 200 Stäbler withdrew to Moravia to form a community at Austerlitz.[43]

Persecution in South Tyrol brought many refugees to Moravia, many of whom formed into communities that practised community of goods. Jacob Hutter was instrumental in organizing these into what became known as the Hutterites. But others came from Silesia, Switzerland, German lands, and the Low Countries. With the passing of time and persecution, all the other versions of Anabaptism would die out in Moravia leaving only the Hutterites. Even the Hutterites would be dissipated by persecution, with a remnant fleeing to Transylvania, then to the Ukraine, and finally to North America in 1874.[44] [45]

South and central Germany, Austria and Alsace

South German Anabaptism had its roots in German mysticism. Andreas Karlstadt, who first worked alongside Martin Luther, is seen as a forerunner of South German Anabaptism because of his reforming theology that rejected many Catholic practices, including infant baptism. However, Karlstadt is not known to have been "rebaptized", nor to have taught it. Hans Denck and Hans Hut, both with German Mystical background (in connection with Thomas Müntzer) both accepted "rebaptism", but Denck eventually backed off from the idea under pressure. Hans Hut is said to have brought more people into early Anabaptism than all the other Anabaptist evangelists of his time put together. However, there may have been confusion about what his baptism (at least some of the times it was done by making the sign of the Tau on the forehead) may have meant to the recipient. Some seem to have taken it as a sign by which they would escape the apocalyptical revenge of the Turks that Hut predicted. Hut even went so far as to predict a 1528 coming of the kingdom of God. When the prediction failed, some of his converts became discouraged and left the Anabaptist movement. The large congregation of Anabaptists at Augsburg fell apart (partly because of persecution) and those who stayed with Anabaptist ideas were absorbed into Swiss and Moravia Anabaptist congregations.[46]:35–117[15] Pilgram Marpeck was another notable leader in early South German Anabaptism who attempted to steer between the two extremes of Denck's inner Holiness and the legalistic standards of the other Anabaptists.[47]

Persecutions and migrations

Roman Catholics and Protestants alike persecuted the Anabaptists, resorting to torture and execution in attempts to curb the growth of the movement. The Protestants under Zwingli were the first to persecute the Anabaptists, with Felix Manz becoming the first Anabaptist martyr in 1527. On May 20 or 21, 1527, Roman Catholic authorities executed Michael Sattler.[49] King Ferdinand declared drowning (called the third baptism) "the best antidote to Anabaptism". The Tudor regime, even the Protestant monarchs (Edward VI of England and Elizabeth I of England), persecuted Anabaptists as they were deemed too radical and therefore a danger to religious stability.

The persecution of Anabaptists was condoned by the ancient laws of Theodosius I and Justinian I which were passed against the Donatists, and decreed the death penalty for anyone who practised rebaptism. Martyrs Mirror, by Thieleman J. van Braght, describes the persecution and execution of thousands of Anabaptists in various parts of Europe between 1525 and 1660. Continuing persecution in Europe was largely responsible for the mass emigrations to North America by the Amish, Hutterites, and Mennonites. Unlike Calvinists, Anabaptists failed to gain recognition in the Peace of Westphalia of 1648 and as a result, they continued to be persecuted in Europe long after that treaty was signed.

Types

Different types exist among the Anabaptists, although the categorizations tend to vary with the scholar's viewpoint on origins. Estep claims that in order to understand Anabaptism, one must "distinguish between the Anabaptists, inspirationists, and rationalists". He classes the likes of Blaurock, Grebel, Balthasar Hubmaier, Manz, Marpeck, and Simons as Anabaptists. He groups Müntzer, Storch, et al. as inspirationists, and anti-trinitarians such as Michael Servetus, Juan de Valdés, Sebastian Castellio, and Faustus Socinus as rationalists. Mark S. Ritchie follows this line of thought, saying, "The Anabaptists were one of several branches of 'Radical' reformers (i.e. reformers that went further than the mainstream Reformers) to arise out of the Renaissance and Reformation. Two other branches were Spirituals or Inspirationists, who believed that they had received direct revelation from the Spirit, and rationalists or anti-Trinitarians, who rebelled against traditional Christian doctrine, like Michael Servetus."

Those of the polygenesis viewpoint use Anabaptist to define the larger movement, and include the inspirationists and rationalists as true Anabaptists. James M. Stayer used the term Anabaptist for those who rebaptized persons already "baptized" in infancy. Walter Klaassen was perhaps the first Mennonite scholar to define Anabaptists that way in his 1960 Oxford dissertation. This represents a rejection of the previous standard held by Mennonite scholars such as Bender and Friedmann.

Another method of categorization acknowledges regional variations, such as Swiss Brethren (Grebel, Manz), Dutch and Frisian Anabaptism (Menno Simons, Dirk Philips), and South German Anabaptism (Hübmaier, Marpeck).

Historians and sociologists have made further distinctions between radical Anabaptists, who were prepared to use violence in their attempts to build a New Jerusalem, and their pacifist brethren, later broadly known as Mennonites. Radical Anabaptist groups included the Münsterites, who occupied and held the German city of Münster in 1534–1535, and the Batenburgers, who persisted in various guises as late as the 1570s.

Spirituality

Charismatic manifestations

Within the inspirationist wing of the Anabaptist movement, it was not unusual for charismatic manifestations to appear, such as dancing, falling under the power of the Holy Spirit, "prophetic processions" (at Zurich in 1525, at Munster in 1534 and at Amsterdam in 1535),[50] and speaking in tongues.[51] In Germany some Anabaptists, "excited by mass hypnosis, experienced healings, glossolalia, contortions and other manifestations of a camp-meeting revival".[52] The Anabaptist congregations that later developed into the Mennonite and Hutterite churches tended not to promote these manifestations, but did not totally reject the miraculous. Pilgram Marpeck, for example, wrote against the exclusion of miracles: "Nor does Scripture assert this exclusion ... God has a free hand even in these last days." Referring to some who had been raised from the dead, he wrote: "Many of them have remained constant, enduring tortures inflicted by sword, rope, fire and water and suffering terrible, tyrannical, unheard-of deaths and martyrdoms, all of which they could easily have avoided by recantation. Moreover one also marvels when he sees how the faithful God (Who, after all, overflows with goodness) raises from the dead several such brothers and sisters of Christ after they were hanged, drowned, or killed in other ways. Even today, they are found alive and we can hear their own testimony ... Cannot everyone who sees, even the blind, say with a good conscience that such things are a powerful, unusual, and miraculous act of God? Those who would deny it must be hardened men."[53] The Hutterite Chronicle and the Martyrs Mirror record several accounts of miraculous events, such as when a man named Martin prophesied while being led across a bridge to his execution in 1531: "this once yet the pious are led over this bridge, but no more hereafter". Just "a short time afterwards such a violent storm and flood came that the bridge was demolished".[54]

Holy Spirit leadership

The Anabaptists insisted upon the "free course" of the Holy Spirit in worship, yet still maintained it all must be judged according to the Scriptures.[55] The Swiss Anabaptist document titled "Answer of Some Who Are Called (Ana-)Baptists – Why They Do Not Attend the Churches". One reason given for not attending the state churches was that these institutions forbade the congregation to exercise spiritual gifts according to "the Christian order as taught in the gospel or the Word of God in 1 Corinthians 14". "When such believers come together, 'Everyone of you (note every one) hath a psalm, hath a doctrine, hath a revelation, hath an interpretation', and so on. When someone comes to church and constantly hears only one person speaking, and all the listeners are silent, neither speaking nor prophesying, who can or will regard or confess the same to be a spiritual congregation, or confess according to 1 Corinthians 14 that God is dwelling and operating in them through His Holy Spirit with His gifts, impelling them one after another in the above-mentioned order of speaking and prophesying."[56]

Today

Anabaptists

Several existing denominational bodies are the direct successors of the continental Anabaptists. Mennonites, Amish and Hutterites are in a direct and unbroken line back to the Anabapists of the early 16th century. Schwarzenau Brethren and River Brethren emerged in the 18th century and adopted many Anabapist elements. The same is true for the Bruderhof Communities that emerged in the early 20th century.[57] Sometimes the Apostolic Christian Church is seen as Neutäufer ("Neo-Anabaptist").[58] Some historical connections have been demonstrated for all of these spiritual descendants, though perhaps not as clearly as the noted institutionally lineal descendants.

Although many see the more well-known Anabaptist groups (Amish, Hutterites and Mennonites) as ethnic groups, only the Amish and the Hutterites today are composed almost totally of descendants of the continental Anabaptists, while among the Mennonites there are Ethnic Mennonites and others who are not. Brethren groups have mostly lost their ethnic distinctiveness.

Total worldwide membership of the Mennonite, Brethren in Christ and related churches totals 1,616,126 (as of 2009) with about 60 percent in Africa, Asia and Latin America.[59] In 2015 there were some 300,000 Amish, more than 200,000 "Russian" Mennonites in Latin America, some 60,000 to 80,000 Old Order Mennonites and some 50,000 Hutterites, who have preserved their ethnicity, their German dialects (Pennsylvania German, Plautdietsch, Hutterisch), plain dress and other old traditions.

Similar groups

The Bruderhof Communities were founded in Germany by Eberhard Arnold in 1920,[60] establishing and organisationally joining the Hutterites in 1930. The group moved to England after the Gestapo confiscated their property in 1933, and they subsequently moved to Paraguay in order to avoid military conscription, and after World War II, they moved to the United States.[61]

Groups which are derived from the Schwarzenau Brethren, often called German Baptists, while not directly descended from the 16th-century Anabaptists, are usually considered Anabaptist because their doctrine and practice are almost identical to the doctrine and practice of Anabaptism. The modern-day Brethren movement is a combination of Anabaptism and Radical Pietism.

The relationship between Baptists and Anabaptists was originally strained. In 1624, the then five existing Baptist churches of London issued a condemnation of the Anabaptists.[62] Puritans of England and their Baptist branch arose independently, and although they may have been informed by Anabaptist theology, they clearly differentiate themselves from Anabaptists as seen in the London Baptist Confession of Faith A.D. 1644, "Of those Churches which are commonly (though falsely) called ANABAPTISTS".[63] Moreover, Baptist historian Chris Traffanstedt maintains that Anabaptists share "some similarities with the early General Baptists, but overall these similarities are slight and not always relational. In the end, we must come to say that this group of Christians does not reflect the historical teaching of the Baptists".[64] German Baptists are not related to the English Baptist movement and were inspired by central European Anabaptists. Upon moving to the United States, they associated with Mennonites and Quakers.

Anabaptist characters exist in popular culture, most notably Chaplain Tappman in Joseph Heller's novel Catch-22, James (Jacques) in Voltaire's novella Candide, Giacomo Meyerbeer's opera Le prophète (1849), and the central character in the novel Q, by the collective known as "Luther Blissett".

Neo-Anabaptists

The term Neo-Anabaptist has been used to describe a late twentieth and early twenty-first century theological movement within American evangelical Christianity which draws inspiration from theologians who are located within the Anabaptist tradition but are ecclesiastically outside it. Neo-Anabaptists have been noted for their "low church, counter-cultural, prophetic-stance-against-empire ethos" as well as for their focus on pacifism, social justice and poverty.[65][66] The works of Mennonite theologians Ron Sider and John Howard Yoder are frequently cited as having a strong influence on the movement.[67]

Legacy

Common Anabaptist beliefs and practices of the 16th century continue to influence modern Christianity and Western society.

- Voluntary church membership and believer's baptism

- Freedom of religion – liberty of conscience

- Separation of church and state

- Separation or nonconformity to the world

- Nonresistance, interpreted as pacifism by modernized groups

- Priesthood of all believers

The Anabaptists were early promoters of a free church and freedom of religion (sometimes associated with separation of church and state).[lower-alpha 5] When it was introduced by the Anabaptists in the 15th and 16th centuries, religious freedom which was independent from the state was unthinkable to both clerical and governmental leaders. Religious liberty was equated with anarchy; Kropotkin[69] traces the birth of anarchist thought in Europe to these early Anabaptist communities.

According to Estep:

Where men believe in the freedom of religion, supported by a guarantee of separation of church and state, they have entered into that heritage. Where men have caught the Anabaptist vision of discipleship, they have become worthy of that heritage. Where corporate discipleship submits itself to the New Testament pattern of the church, the heir has then entered full possession of his legacy.[70]

See also

- Adrianists

- Amish Mennonite

- Christian anarchism

- Christian communism

- Christian socialism

- Clancularii

- Conservative Mennonites

- Donatists (first historical occurrence of re-baptism)

- Funkite

- List of Anabaptist churches

- Melchior Rink, a central-German Anabaptist leader during the sixteenth-century

- Peace churches

- Restorationism

- Shtundists

Notes

- Since the middle of the 20th century, the German-speaking world no longer uses the term Wiedertäufer (translation: "Re-baptizers"), considering it biased. The term Täufer (translation: "Baptizers") is now used, which is considered more impartial. From the perspective of their persecutors, the "Baptizers" baptized for the second time those "who as infants had already been baptized". The denigrative term Anabaptist signifies rebaptizing and is considered a polemical term, so it has been dropped from use in modern German. However, in the English-speaking world, it is still used to distinguish the Baptizers more clearly from the Baptists, a Protestant sect that developed later in England. Compare their self-designation as "Brethren in Christ" or "Church of God": Stayer, James M. (2001). "Täufer". Theologische Realenzyklopädie (TRE) (in German). 32. Berlin, New York: Walter de Gruyter. pp. 597–617. ISBN 3-11-016712-3.

Brüder in Christo", "Gemeinde Gottes

. - For example, those of the Münster Rebellion or Balthasar Hubmaier.

- A "true church" movement is a part of the Protestant or Reformed group of Christianity that claims to represent the true faith and order of New Testament Christianity. Most only assert this in relation to their church doctrines, polity, and practice (e.g., the ordinances), while a few hold they are the only true Christians. Some examples of Anabaptistic true church movements are the Landmark Baptists and the Church of God in Christ, Mennonite. The Church of God, the Stone-Campbell restoration movement, and others represent a variation in which the "true church" apostatized and was restored, in distinction to this idea of apostolic or church succession. These groups trace their "true church" status through means other than those generally accepted by Roman Catholicism or Orthodox Christianity, both of which likewise claim to represent the true faith and order of New Testament Christianity.

- Such as the Adoptionism of the Paulicianists; some of the other groups often cited were in fact little different from the Catholics and bore little similarity to modern Baptists.

- The origins of religious freedom in the United States are traced back to the Anabaptists.[68]

References

- "Anabaptist, n.", Oxford English Dictionary, Oxford University Press, December 2012, retrieved January 21, 2013

- "Anabaptism, n.", Oxford English Dictionary, Oxford University Press, December 2012, retrieved January 21, 2013

- Klaassen 1973.

- McGrath, William, The Anabaptists: Neither Catholic nor Protestant (PDF), Hartville, OH: The Fellowship Messenger, archived from the original (PDF) on December 27, 2016

- Gilbert, William (1998), "The Radicals of the Reformation", Renaissance and Reformation, Lawrence, KS: University of Kansas

- Bruening, Michael W. (April 5, 2017). A Reformation Sourcebook: Documents from an Age of Debate. University of Toronto Press. p. 134. ISBN 9781442635708.

In 1527, Sattler presided over a meeting at Schleitheim (in canton Schaffhausen, on the Swiss/German border), where Anabaptist leaders drew up the Schleitheim Confession of Faith (doc. 29). Sattler was arrested and executed soon afterwards. Anabaptist groups varied widely in their specific beliefs, but the Schleitheim Confession represents foundational Anabaptist beliefs as well as any single document can.

- Hershberger, Guy F. (March 6, 2001). The Recovery of the Anabaptist Vision. Wipf & Stock Publishers. p. 65. ISBN 9781579106003.

The Schleitheim articles are Anabaptism's oldest confessional document.

- Harper, Douglas (2010) [2001], "Anabaptist", Online Etymological Dictionary, retrieved April 25, 2011

- Vedder, Henry Clay (1905), , New York: G. P. Putnam's Sons, p. 204.

- Dyck 1967, p. 45

- Wagner, Murray L (1983). Petr Chelčický: A Radical Separatist in Hussite Bohemia. Scottdale, PA: Herald Press. p. 20. ISBN 0-8361-1257-1.

- van der Zijpp, Nanne. "Sacramentists". Global Anabaptist Mennonite Encyclopedia Online. Archived from the original on February 27, 2007. Retrieved April 12, 2007.

- Fontaine, Piet FM (2006). "Chapter I – part 1 Radical Reformation – Dutch Sacramentists". The Light and the Dark: A Cultural History of Dualism. XXIII. Postlutheran Reformation. Utrecht: Gopher Publishers. Archived from the original on May 9, 2007.

- van Braght 1950, p. 277.

- Stayer 1994.

- Estep 1963, p. 5: 'Too much has been said of Münster. It belongs on the fringe of Anabaptist life which was completely divorced from the evangelical, biblical heart of the movement'

- Dyck 1967, p. 49.

- Stayer, James M; Packull, Werner O; Deppermann, Klaus (April 1975), "From Monogenesis to Polygenesis: the historical discussion of Anabaptist origins", Mennonite Quarterly Review, 49 (2)

- Stayer 1994, p. 86.

- Hall, Thor. "Possibilities of Erasmian Influence on Denck and Hubmaier in Their Views of Freedom of the Will." Mennonite Quarterly Review 35 (1961): 149-70.

- Davis, Kenneth R. "Erasmus as a Progenitor of Anabaptist Theology and Piety." Mennonite Quarterly Review 47 (1973): 163-78.

- Kreider, Robert. "Anabaptism and Humanism: an Inquiry Into the Relationship of Humanism to the Evangelical Anabaptists." Mennonite Quarterly Review 26 (1952): 123-41.

- Klager, Andrew P. 'Truth is immortal': Balthasar Hubmaier (c.1480-1528) and the Church Fathers. PhD thesis. Glasgow: University of Glasgow, 2011, pp. 28–32.

- Klager, Andrew P. "Balthasar Hubmaier’s Use of the Church Fathers: Availability, Access and Interaction." Mennonite Quarterly Review 84, no. 1 (January 2010): 5–65.

- Carrol, JM (1931). The Trail of Blood. Lexington, KY: Ashland Avenue Baptist Church. Archived from the original on February 21, 2009.

- Ruth, John L. (1975). Conrad Grebel, Son of Zurich. Scottdale, PA: Herald Press. p. 79. ISBN 0-8361-1767-0.

- Dyck 1967, p. 46.

- The Chronicle of the Hutterian Brethren, Known as Das grosse Geschichtbuch der Hutterischen Brüder. Rifton, New York: Plough Pub. House. 1987. p. 45.

- "1525, The Anabaptist Movement Begins". Retrieved December 27, 2017.

- Klaassen, Walter (1985). "A Fire That Spread Anabaptist Beginnings". Waterloo, ON, Canada: Christian History Institute. Retrieved December 27, 2017.

- Hoover, Peter (2008). The Mystery of the Mark-Anabaptist Mission Work under the Fire of God. Mountain Lake, Minnesota: Elmendorf Books. pp. 14–66.

- Packull 1995, pp. 169–75.

- Packull 1995, pp. 181–5.

- Packull 1995, p. 280.

- Estep 1963, p. 109.

- Estep 1963, p. 111.

- Dyck 1967, p. 105.

- Dyck 1967, p. 111.

- Estep 1963, p. 89.

- Packull 1995, p. 54.

- Dyck 1967, p. 67.

- Packull 1995, p. 55.

- Packull 1995, p. 61.

- Packull 1995.

- Sreenivasan, Jyotsna (2008). Utopias in American History. ABC-CLIO. pp. 175–6.

- Packull, Werner O (1977). Mysticism and the Early South German-Austrian Anabaptist Movement 1525–1531. Scottdale, PA: Herald Press. ISBN 0-8361-1130-3.

- Loewen, Harry; Nolt, Steven (1996). Through Fire & Water. Scottdale, PA: Herald Press. pp. 136–137.

- "Ursel (d. 1570)". GAMEO. January 10, 2018. Retrieved June 16, 2019.

- Bossert, Jr., Gustav; Bender, Harold S.; Snyder, C. Arnold (2017). "Sattler, Michael (d. 1527)". In Roth, John D. (ed.). Global Anabaptist Mennonite Encyclopedia Online, reprinted from Bossert, Jr., Gustav; Bender, Harold S.; Snyder, C. Arnold (1989). Bender, Harold S. (ed.). Mennonite Encyclopedia. Harrisonburg, VA: Herald Press. Vol. 4, pp. 427–434, 1148; vol. 5, pp. 794–795.

- Klaassen 1973, p. 63.

- Little, Franklin H (1964), The Origins of Sectarian Protestantism, New York: Beacons, p. 19

- Williams 2000, p. 667.

- Marpeck 1978, p. 50.

- van Braght 1950, p. 440.

- Oyer, John S (1964), Lutheran Reformers Against Anabaptists, The Hague: M Nijhoff, p. 86

- Peachey, Paul; Peachey, Shem, eds. (1971), "Answer of Some Who Are Called (Ana-)Baptists – Why They Do Not Attend the Churches", Mennonite Quarterly Review, 45 (1): 10, 11

- "Life Among The Bruderhof". The American Conservative. Retrieved May 23, 2017.

- "Apostolic Christian Church of America".

- Mennonite World Conference (December 1, 2009), New global map locates 1.6 million Anabaptists, Mennonite Brethren Herald

- "About Us". Plough. Retrieved May 23, 2017.

- "Church Community is a Gift of the Holy Spirit – The Spirituality of the Bruderhof | Anabaptism | Religion & Spirituality". Scribd. Retrieved September 27, 2017.

- Melton, JG (1994), "Baptists", Encyclopedia of American Religions

- "London Baptist Confession of 1644". spurgeon.org. Archived from the original on June 17, 2010.

Of those Churches which are commonly (though falsely) called ANABAPTISTS;

- Traffanstedt, Chris (1994), "Baptists", A Primer on Baptist History: The True Baptist Trail, archived from the original on September 11, 2013

- DeYoung, Kevin. "The Neo-Anabaptists". The Gospel Coalition. Retrieved March 25, 2017.

- Hiebert, Jared; Hiebert, Terry G. (Fall 2013). "New Calvinists and Neo-Anabaptists: A Tale of Two Tribes". Direction: A Mennonite Brethren Forum. 42 (2): 178–194. Retrieved March 25, 2017.

- Tooley, Mark. "Mennonite Takeover?". The American Spectator. Archived from the original on March 26, 2017. Retrieved March 25, 2017.

- Verduin, Leonard (1998), That First Amendment and The Remnant, The Christian Hymnary, ISBN 1-890050-17-2

- Kropotkin, Peter (1910), "Anarchism", The Encyclopædia Britannica

- Estep 1963, p. 232.

Sources

- van Braght, Thieleman J (1950) [1938], Martyrs Mirror, Scottdale, PA: Herald Press, ISBN 978-0-8361-1390-7.

- Carroll, J.M. (1931). The Trail of Blood: Following the Christians Down through the Ages, or, the history of Baptist Churches from the Time of Christ, Their Founder, to the Present Day. Lexington, Ky.: Ashland Avenue Baptist Church. 56 p. + fold. chart. Without ISBN

- Dyck, Cornelius J (1967), An Introduction to Mennonite History, Scottdale, PA: Herald Press, ISBN 0-8361-1955-X.

- Estep, William R (1963), The Anabaptist Story, Grand Rapids, MI: William B Eerdmans, ISBN 0-8028-1594-4.

- Klaassen, Walter (1973), Anabaptism: Neither Catholic Nor Protestant, Waterloo, ON: Conrad Press.

- Knox, Ronald. Enthusiasm: a Chapter in the History of Religion, with Special Reference to the XVII and XVIII Centuries. Oxford, Eng.: Oxford University Press, 1950. viii, 622 p.

- Marpeck, Pilgram (1978), Klassen, William; Klassen, Walter (eds.), Covenant and Community: The Life, Writings, and Hermeneutics, Scottdale, PA: Herald.

- Packull, Werner O (1995), Hutterite Beginnings: Communitarian Experiments During the Reformation, Baltimore, Maryland: The Johns Hopkins University Press, ISBN 0-8018-6256-6.

- Stayer, James M (1994) [1991], The German Peasants' War and Anabaptist Community of Goods, Montréal: McGill-Queen's Press, MQUP, ISBN 0-7735-0842-2.

- Williams, George Hunston (2000) [1962], The Radical Reformation (3rd ed.), Truman State University Press, ISBN 0-664-20372-8.

Further reading

- Newman, Albert H, A History of Anti-Pedobaptism, From the Rise of Pedobaptism to AD 1609, Google Books, ISBN 1-57978-536-0.

- Hillerbrand, Hans, Anabaptist Bibliography 1520–1630, Google Books, ISBN 0-910345-03-1.

- Fast, Heinhold (1999). "Anabaptists". In Erwin Fahlbusch and Geoffrey William Bromiley (ed.). The Encyclopedia of Christianity. 1. Grand Rapids, MI: Wm. B. Eerdmans. pp. 45–48. ISBN 0802824137.

- James M. Stayer. "Anabaptists and the Sword". ISBN 0-87291-081-4.

- Mary E. Bamford. Harrison, Larry (ed.). "In Editha's Days. A Tale of Religious Liberty" (The Bible Makes Us Baptists ed.). LCCN 06006296.

- Harold S. Bender; Dyck, Cornelius J.; Martin, Dennis D.; Smith, Henry C. (eds.). Mennonite Encyclopedia. ISBN 0-8361-1018-8.

- Baylor, Michael G. "Revelation & Revolution: Basic Writings of Thomas Muntzer". ISBN 0-934223-16-5.

- Bender, Harold S. "The Anabaptist Vision". ISBN 0-8361-1305-5.)

- Verduin, Leonard. "The Anatomy of a Hybrid : a Study in Church-State Relationships". ISBN 0-8028-1615-0.

- Thieleman J. van Braght. "The Bloody Theater or Martyrs Mirror". ISBN 0-8361-1390-X.

- J. Gordon Melton (ed.). "The Encyclopedia of American Religions". ISBN 0-8103-6904-4.

- Pearse, Meic, The Great Restoration: The Religious Radicals of the 16th and 17th Centuries.

- Cohn, Norman. "The Pursuit of the Millennium". Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-500456-6.

- Verduin, Leonard. "The Reformers and their Stepchildren". ISBN 0-8010-9284-1.

- Peter Hoover. "The Secret of the Strength" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on April 12, 2019. Retrieved December 27, 2017. Alt URL

- Arthur, Anthony. "The Tailor King: The Rise and Fall of the Anabaptist Kingdom of Munster". ISBN 0-312-20515-5.)

- Ham, Paul (2018). New Jerusalem: The short life and terrible death of Christendom's most defiant sect. Sydney: Random House Australia. ISBN 9780143781332.

External links

| Library resources about Anabaptism |

- Anabaptism at Curlie

- "Anabaptism". Global Anabaptist Mennonite Encyclopedia Online. Retrieved September 11, 2013.

- Anabaptist History Complete Playlist (Parts 1–20) history of the movement from the Bible to present. (YouTube videos, 27 hours)

- "The Story of the Church: The Protestant Reformation: The Anabaptists and Other Radical Reformers". Ritchie Family Page. Archived from the original on December 17, 2005. Retrieved December 15, 2005.

- "The Anabaptist Story". The Reformed Reader. Archived from the original on December 15, 2005. Retrieved December 15, 2005.

- The Rise and Fall of the Anabaptists, by E. Belfort Bax 1903