Battle of the Tenaru

The Battle of the Tenaru, sometimes called the Battle of the Ilu River or the Battle of Alligator Creek, was a land battle between the Imperial Japanese Army and Allied ground forces that took place on August 21, 1942 on the island of Guadalcanal during the Pacific campaign of World War II. The battle was the first major Japanese land offensive during the Guadalcanal campaign.

In the battle, U.S. Marines, under the overall command of U.S. Major General Alexander Vandegrift, repulsed an assault by the "First Element" of the "Ichiki" Regiment, under the command of Japanese Colonel Kiyonao Ichiki. The Marines were defending the Lunga perimeter, which guarded Henderson Field, which was captured by the Allies in landings on Guadalcanal on August 7. Ichiki's unit was sent to Guadalcanal in response to the Allied landings with the mission of recapturing the airfield and driving the Allied forces off the island.

Underestimating the strength of Allied forces on Guadalcanal, which at the time numbered about 11,000 personnel, Ichiki's unit conducted a nighttime frontal assault on Marine positions at Alligator Creek on the east side of the Lunga perimeter. Jacob Vouza, a Coastwatcher scout, warned the Americans of the impending attack minutes before Ichiki's assault which was subsequently defeated with heavy losses to the Japanese. The Marines counterattacked Ichiki's surviving troops after daybreak, killing many more. All but 128 of the original 917 of the Ichiki Regiment's First Element died.

The battle was the first of three separate major land offensives by the Japanese in the Guadalcanal campaign. The Japanese realized after Tenaru that Allied forces on Guadalcanal were much greater in number than originally estimated and sent larger forces to the island for their subsequent attempts to retake Henderson Field.

Background

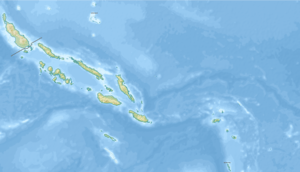

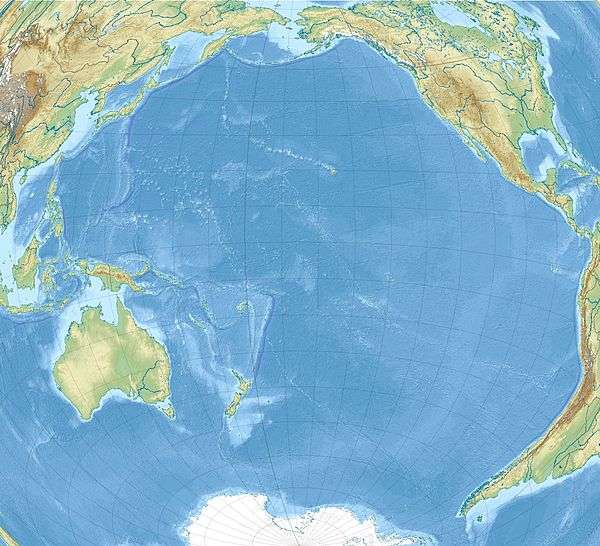

On August 7, 1942, U.S. forces landed on Guadalcanal, Tulagi, and Florida Islands in the Solomon Islands. The landings on the islands were meant to deny their use by the Japanese as bases for threatening the supply routes between the U.S. and Australia, and to secure the islands as starting points for a campaign with the eventual goal of isolating the major Japanese base at Rabaul while also supporting the Allied New Guinea campaign. The landings initiated the six-month-long Guadalcanal campaign.[7]

Taking the Japanese by surprise, the Allied landing forces accomplished their initial objectives of securing Tulagi and nearby small islands, as well as an airfield under construction at Lunga Point on Guadalcanal, by nightfall on August 8.[8] That night, as the transports unloaded, the Allied warships screening the transports were surprised and defeated by an Imperial fleet of seven cruisers and one destroyer, commanded by Japanese Vice Admiral Gunichi Mikawa. One Australian and three U.S. cruisers were sunk and one other U.S. cruiser and two destroyers were damaged in the Battle of Savo Island. Rear Admiral Richmond K. Turner withdrew all remaining Allied naval forces by the evening of August 9 without unloading all the heavy equipment, provisions, and troops from the transports, although most of the divisional artillery was landed, consisting of thirty-two 75 mm and 105 mm howitzers. Only five days' rations were landed.[9][10]

The Marines ashore on Guadalcanal initially concentrated on forming a defense perimeter around the airfield, moving the landed supplies within the perimeter, and finishing the airfield. Vandegrift placed his 11,000 troops on Guadalcanal in a loose perimeter around the Lunga Point area. In four days of intense effort, the supplies were moved from the landing beach into dispersed dumps within the perimeter. Work began on the airfield immediately, mainly using captured Japanese equipment. On August 12, the airfield was named Henderson Field after Major Lofton Henderson, a Marine aviator who had been killed at the Battle of Midway. Captured Japanese stock increased the total supply of food to 14 days worth. To conserve the limited food supplies, the Allied troops were limited to two meals per day.[11][12]

In response to the Allied landings on Guadalcanal, the Japanese Imperial General Headquarters assigned the Imperial Japanese Army's 17th Army, a corps-sized command based at Rabaul and under the command of Lieutenant-General Harukichi Hyakutake, with the task of retaking Guadalcanal from Allied forces. The 17th Army, currently heavily involved with the Japanese campaign in New Guinea, had only a few units available to send to the southern Solomons area. Of these units, the 35th Infantry Brigade under Major General Kiyotake Kawaguchi was at Palau, the 4th (Aoba) Infantry Regiment was in the Philippines, and the 28th (Ichiki) Infantry Regiment, under the command of Colonel Kiyonao Ichiki, was at sea en route to Japan from Guam.[13] The different units began to move towards Guadalcanal immediately, but Ichiki's regiment, being the closest, arrived first.[14]

An aerial reconnaissance of the U.S. Marine positions on Guadalcanal on August 12 by one of the senior Japanese staff officers from Rabaul sighted few U.S. troops in the open and no large ships in the waters nearby, convincing Imperial Headquarters that the Allies had withdrawn the majority of their troops. In fact, none of the Allied troops had been withdrawn.[15] Hyakutake issued orders for an advance unit of 900 troops from Ichiki's regiment to be landed on Guadalcanal by fast warship to immediately attack the Allied position and reoccupy the airfield area at Lunga Point. The remaining personnel in Ichiki's regiment would be delivered to Guadalcanal by slower transport later. At the major Japanese naval base at Truk, which was the staging point for delivery of Ichiki's regiment to Guadalcanal, Colonel Ichiki was briefed that 2,000–10,000 U.S. troops were holding the Guadalcanal beachhead and that he should, "avoid frontal attacks."[16]

Ichiki and 916 of his regiment's 2,300 troops, designated the "First Element" and carrying seven days' supply of food, were delivered to Taivu Point, about 35 kilometers (22 miles) east of Lunga Point, by six destroyers at 01:00 on August 19.[17] Ichiki was ordered to scout the American positions and wait for the remainder of his force to arrive. Known as the Ichiki Butai (Ichiki Detachment), they were an elite and battle-seasoned force but as was about to be discovered, they were heavily stricken with "victory disease" – overconfidence due to previous success. Ichiki was so confident in the superiority of his men that he decided to destroy the American defenders before the remaining majority of his force arrived, even writing in his journal "18 August, landing; 20 August, march by night and battle; 21 August, enjoyment of the fruit of victory".[18] He concocted a brazenly simple plan: march straight down the beach and through the American defenses.[19] Leaving about 100 personnel behind as a rear guard, Ichiki marched west with the remaining 800 men of his unit and made camp before dawn about 14 kilometers (8.7 miles) east of the Lunga perimeter. The U.S. Marines at Lunga Point received intelligence that a Japanese landing had occurred and took steps to find out exactly what was happening.[20]

Prelude

Reports to Allied forces from patrols of Solomon Islanders, including retired Sergeant Major Jacob C. Vouza of the British Solomon Islands Protectorate Constabulary, under the direction of Martin Clemens, a coastwatcher and officer in the British Solomon Islands Protectorate Defence Force (BSIPDF), along with Allied intelligence from other sources, indicated that Japanese troops were present east of Lunga Point. To investigate further, on August 19, a Marine patrol of 60 men and four native scouts, commanded by U.S. Marine Captain Charles H. Brush, marched east from the Lunga Perimeter.[21][22]

At the same time, Ichiki sent forward his own patrol of 38 men, led by his communications officer, to reconnoiter Allied troop dispositions and establish a forward communications base. Around 12:00 on August 19 at Koli Point, Brush's patrol sighted and ambushed the Japanese patrol, killing all but five of its members, who escaped back to Taivu. The Marines suffered three dead and three wounded.[23]

Papers discovered on the bodies of some of the Japanese officers in the patrol revealed that they belonged to a much larger unit and showed detailed intelligence of U.S. Marine positions around Lunga Point.[24] The papers did not, however, detail exactly how large the Japanese force was or whether an attack was imminent.[25]

Now anticipating an attack from the east, the U.S. Marine forces, under the direction of General Vandegrift, prepared their defenses on the east side of the Lunga perimeter. Several official U.S. military histories identify the location of the eastern defenses of the Lunga perimeter as emplaced on the Tenaru River. The Tenaru River, however, was actually located further to the east. The river forming the eastern boundary of the Lunga perimeter was actually the Ilu River, nicknamed Alligator Creek by the Marines, a double misnomer: there are only crocodiles (no alligators) in the Solomons, and Alligator "Creek" was a tidal lagoon separated from the ocean by a sandbar about 7 to 15 meters (23 to 49 ft) wide and 30 meters (98 feet) long.[26]

Along the west side of Alligator Creek, Colonel Clifton B. Cates, commander of the 1st Marine Regiment, deployed his 1st (LtCol Cresswell) and 2nd battalions (LtCol Pollock).[27][28] To help further defend the Alligator Creek sandbar, Cates deployed 100 men from the 1st Special Weapons Battalion with two 37mm anti-tank guns equipped with canister shot.[29] Marine divisional artillery, consisting of both 75mm and 105mm guns, pre-targeted locations on the east side and sandbar areas of Alligator Creek, and forward artillery observers emplaced themselves in the forward Marine positions.[30] The Marines worked all day on August 20 to prepare their defenses as much as possible before nightfall.[27]

Learning of the annihilation of his patrol, Ichiki quickly sent forward a company to bury the bodies and followed with the rest of his troops, marching throughout the night of August 19 and finally halting at 04:30 on August 20 within a few miles of the U.S. Marine positions on the east side of Lunga Point. At this location, he prepared his troops to attack the Allied positions that night.[31]

Battle

Just after midnight on August 21, Ichiki's main body of troops arrived at the east bank of Alligator Creek and were surprised to encounter the Marine positions, not having expected to find U.S. forces located that distance from the airfield.[32] Nearby U.S. Marine listening posts heard "clanking" sounds, human voices, and other noises before withdrawing to the west bank of the creek. At 01:30 Ichiki's force opened fire with machine guns and mortars on the Marine positions on the west bank of the creek, and a first wave of about 100 Imperial soldiers charged across the sandbar towards the Marines.[33]

Marine machine gun fire and canister rounds from the 37 mm cannons killed most of the Japanese soldiers as they crossed the sandbar. A few of the Japanese soldiers reached the Marine positions, engaged in hand to hand combat with the defenders, and captured a few of the Marine front-line emplacements. Also, Japanese machine gun and rifle fire from the east side of the creek killed several of the Marine machine-gunners.[34] A company of Marines, held in reserve just behind the front line, attacked and killed most, if not all, of the remaining Japanese soldiers that had breached the front line defenses, ending Ichiki's first assault about an hour after it had begun.[35][36]

At 02:30 a second wave of about 150 to 200 Japanese troops again attacked across the sandbar and was again almost completely wiped out. At least one of the surviving Imperial officers from this attack advised Ichiki to withdraw his remaining forces, but Ichiki declined to do so.[37]

As Ichiki's troops regrouped east of the creek, Japanese mortars bombarded the Marine lines.[38] The Marines answered with 75 mm artillery barrages and mortar fire into the areas east of the creek.[39] At about 05:00, another wave of Japanese troops attacked, this time attempting to flank the Marine positions by wading through the ocean surf and attacking up the beach into the west bank area of the creek bed. The Marines responded with heavy machine gun and artillery fire along the beachfront area, again causing heavy casualties among Ichiki's attacking troops and causing them to abandon their attack and withdraw back to the east bank of the creek.[40][41] For the next couple of hours, the two sides exchanged rifle, machine gun, and artillery fire at close range across the sandbar and creek.[42]

In spite of the heavy losses his force had suffered, Ichiki's troops remained in place on the east bank of the creek, either unable or unwilling to withdraw.[43] At daybreak on August 21, the commanders of the U.S. Marine units facing Ichiki's troops conferred on how best to proceed, and they decided to counterattack.[44] The 1st Battalion, 1st Marine Regiment, under Lieutenant Colonel Leonard B. Cresswell, crossed Alligator Creek upstream from the battle area, enveloped Ichiki's troops from the south and east, cutting off any avenue for retreat, and began to "compress" Ichiki's troops into a small area in a coconut grove on the east bank of the creek.[42]

Aircraft from Henderson Field strafed Japanese soldiers who attempted to escape down the beach and, later in the afternoon, four or five Marine M3 Stuart tanks attacked across the sandbar into the coconut grove. The tanks swept the coconut grove with machine gun and canister cannon fire, as well as rolling over the bodies, both alive and dead, of any Japanese soldiers unable or unwilling to get out of the way. When the tank attack was over, Vandegrift wrote that, "the rear of the tanks looked like meat grinders."[45]

By 17:00 on August 21, Japanese resistance had ended. Colonel Ichiki was either killed during the final stages of the battle, or performed ritual suicide (seppuku) shortly thereafter, depending on the account. As curious Marines began to walk around looking at the battlefield, some wounded Japanese troops shot at them, killing or wounding several Marines. Thereafter, Marines shot and/or bayonetted any Japanese soldier lying on the ground that moved, although about 15 injured and unconscious Japanese soldiers were taken prisoner.[46][47] About 30 of the Japanese troops escaped to rejoin their regiment's rear echelon at Taivu Point.[48]

Aftermath

For the U.S. and its allies, the victory in the Tenaru battle was psychologically significant in that Allied soldiers, after a series of defeats by Japanese Army units throughout the Pacific and east Asia, now knew that they could defeat the Imperial Armies in a land battle.[49] The battle also set another precedent that would continue throughout the war in the Pacific, which was the reluctance of defeated Japanese soldiers to surrender and their efforts to continue killing Allied soldiers, even as the Japanese soldiers lay dying on the battlefield. On this subject Vandegrift remarked, "I have never heard or read of this kind of fighting. These people refuse to surrender. The wounded wait until men come up to examine them ... and blow themselves and the other fellow to pieces with a hand grenade."[50] Robert Leckie, a Guadalcanal veteran, recalls the aftermath of the battle in his book Helmet For My Pillow, "Our regiment had killed something like nine hundred of them. Most lay in clusters or heaps before the gun pits commanding sandspit, as though they had not died singly but in groups. Moving among them were the souvenir hunters, picking their way delicately as though fearful of booby traps, while stripping the bodies of their possessions."[51]

The battle was also psychologically significant in that Imperial soldiers believed in their own invincibility and superior spirit. By August 25, most of Ichiki's survivors reached Taivu Point and radioed Rabaul to tell 17th Army headquarters that Ichiki's detachment had been "almost annihilated at a point short of the airfield." Reacting with disbelief to the news, Japanese Army headquarters officers proceeded with plans to deliver additional troops to Guadalcanal to reattempt to capture Henderson Field.[52] The next major Japanese attack on the Lunga perimeter occurred at the Battle of Edson's Ridge about three weeks later, this time employing a much larger force than had been employed in the Tenaru battle.[53]

Depictions

The Battle of the Tenaru is a key part of the 1945 biographical film on Al Schmid, Pride of the Marines. The brunt of the Japanese assault was borne by Marines Cpl. Lee Diamond, PFC. John Rivers and Pvt. Albert Schmid. The three were credited with 200 Japanese killed in action (KIA). Awarded the Navy Cross (America's second highest decoration) for their actions, the trio paid dearly. Rivers lost his life, while Schmid and Diamond suffered horrendous wounds. Schmid lost sight in one eye and was left with very little in the other. Shot in his arm early in the fight, Diamond's arms and hands were also ripped by the same grenade which blinded Schmid.[54]

In 2010, the battle became the climax of the first episode of Steven Spielberg's and Tom Hanks' miniseries, The Pacific.

Notes

- Smith, Bloody Ridge, pp. 14–15; Jersey, Hell's Islands, p. 209. There were approximately 900 Marines in each of the three participating battalions plus additional support troops such as the special weapons unit and the divisional artillery.

- Frank, Guadalcanal, pp. 147, 681.

- Smith, Bloody Ridge, p. 71. Smith says 38 were killed in the battle in addition to the three killed in the Brush patrol.

- Frank, Guadalcanal, pp. 156, 681. Frank says 41 were killed in the battle in addition to the three killed in the Brush patrol.

- Smith, Bloody Ridge, p. 73. Smith says 128 of the original 917 total complement of the 1st echelon survived, meaning 774 were killed after subtracting the 15 captured from the total lost in the battle.

- Frank, Guadalcanal, pp. 156, 681. Frank says 777 were killed.

- Hogue, Pearl Harbor to Guadalcanal, pp. 235–236.

- Morison, Struggle for Guadalcanal, pp. 14–15.

- Zimmerman, The Guadalcanal Campaign, pp. 49–56.

- Smith, Bloody Ridge, pp. 11, 16.

- Shaw, First Offensive, p. 13.

- Smith, Bloody Ridge, pp. 16–17.

- Miller, The First Offensive, p. 96

- Smith, Bloody Ridge, p. 88; Evans, Japanese Navy, p. 158; Frank, Guadalcanal, pp. 141–143. The Ichiki regiment was named after its commanding officer and was part of the 7th Division from Hokkaido. The Aoba regiment, from the 2nd Division, took its name from Aoba Castle in Sendai, because most of the soldiers in the regiment were from Miyagi prefecture (Rottman, Japanese Army, p. 52). Ichiki's regiment had been assigned to invade and occupy Midway Atoll, but were on their way back to Japan after the invasion was cancelled following the Japanese defeat in the Battle of Midway. Although some histories state that Ichiki's regiment was at Truk, Raizo Tanaka, in Evans' book, states that he dropped off Ichiki's regiment at Guam after the Battle of Midway. Ichiki's regiment was subsequently loaded on ships for transport elsewhere but were rerouted to Truk after the Allied landings on Guadalcanal.

- Frank, Guadalcanal, pp. 143–144.

- Evans, Japanese Navy, p. 161; Griffith, Battle for Guadalcanal, pp. 98–99; Smith, Bloody Ridge, p. 31.

- Evans, Japanese Navy, p. 161; Frank, Guadalcanal, p. 145; Jersey, Hell's Islands, p. 204, 212; Morison, Struggle for Guadalcanal, p. 70; Smith, Bloody Ridge, p. 43. The First Element troops were mainly from the 28th's 1st Battalion under a Major Kuramoto and were mostly from Asahikawa, Hokkaidō. At Taivu Point was an Imperial outpost with about 200 naval personnel who assisted with the unloading of Ichiki's forces from the destroyers.

- Spector, Eagle Against the Sun, p. 496

- Gilbert, Marine Tank Battles in The Pacific, p. 41

- Griffith, Battle for Guadalcanal, pp. 99–100; Smith, Bloody Ridge, pp. 29, 43–44.

- Frank, Guadalcanal, p. 148; Jersey, Hell's Islands, p. 205.

- Zimmerman, The Guadalcanal Campaign, p. 62.

- Griffith, Battle for Guadalcanal, p. 100; Jersey, Hell's Islands, p. 205; Smith, Bloody Ridge, p. 47. The U.S. and Japanese soldiers killed in this engagement are included in the total casualty figures for the Tenaru battle. Captain Yoshimi Shibuya was the leader of the Japanese patrol. One of the five Japanese survivors later died of his wounds at Taivu Point.

- Zimmerman, The Guadalcanal Campaign, p. 62

- Frank, Guadalcanal, p. 149.

- Frank, Guadalcanal, p. 150.

- Hammel, Carrier Clash, p. 135.

- Zimmerman, The Guadalcanal Campaign, p. 67.

- Frank, Guadalcanal, p. 151

- Griffith, Battle for Guadalcanal, p. 102.

- Frank, Guadalcanal, pp. 149, 151; Smith, Bloody Ridge, p. 48.

- Smith, Bloody Ridge, p. 58.

- Griffith, Battle for Guadalcanal, p. 102; Hough, Pearl Harbor to Guadalcanal, p. 290; Smith, Bloody Ridge, pp. 58–59.

- Jersey, Hell's Islands, p. 210; Hammel, Carrier Clash, p. 137.

- Zimmerman, The Guadalcanal Campaign, p. 68.

- Frank, Guadalcanal, p. 153.

- Smith, Bloody Ridge, pp. 62–63.

- Griffith, Battle for Guadalcanal, p. 103.

- Frank, Guadalcanal, p. 153; Smith, Bloody Ridge, p. 63.

- Griffith, Battle for Guadalcanal, pp. 103–104.

- Hammel, Carrier Clash, p. 141.

- Zimmerman, The Guadalcanal Campaign, p. 69.

- Frank, Guadalcanal, p. 154; Smith, Bloody Ridge, p. 66.

- Hough, Pearl Harbor to Guadalcanal, p. 290.

- Gilbert, Marine Tank Battles, pp. 42–43; Griffith, Battle for Guadalcanal, p. 106; Jersey, Hell's Islands, p. 212; Smith, Bloody Ridge, p. 66.

- Smith, Bloody Ridge, pp. 71–72. Smith states that most Japanese survivors of the battle insist that Ichiki was killed in action, not by suicide. After the battle, a wounded Japanese officer, apparently feigning death, shot and seriously wounded an inspecting Marine with a small pistol before being killed by another Marine, Andy Poliny. Poliny believes that this was Ichiki.

- Frank, Guadalcanal, p. 156. Frank states that the official Japanese Defense Agency history of the battle (Senshi Sōshō) says that Ichiki committed suicide in the seppuku manner. However, one Japanese survivor's account states that Ichiki was last seen advancing towards the U.S. Marine lines.

- Hough, Pearl Harbor to Guadalcanal, p. 291; Smith, Bloody Ridge, pp. 43, 73. Since 100 troops were left behind as a rear guard and 128 of the unit survived the battle, that means that about 30 escaped from the engagement back to the rear guard area.

- Frank, Guadalcanal, p. 157.

- Griffith, Battle for Guadalcanal, p. 107

- Leckie, Helmet For My Pillow, pp. 84–85

- Frank, Guadalcanal, p. 158; Smith, Bloody Ridge, p. 74.

- Frank, Guadalcanal, p. 245

- Mark DiIonno (February 21, 2010). "HBO series illuminates N.J. Marine's book on World War II experience". NJ.com. Archived from the original on April 29, 2010. Retrieved March 16, 2010.

References

- Evans, David C. (1986). "The Struggle for Guadalcanal". The Japanese Navy in World War II: In the Words of Former Japanese Naval Officers (2nd ed.). Annapolis, Maryland: Naval Institute Press. ISBN 0-87021-316-4.

- Frank, Richard (1990). Guadalcanal: The Definitive Account of the Landmark Battle. New York: Random House. ISBN 0-394-58875-4.

- Gilbert, Oscar E. (2001). Marine Tank Battles in the Pacific. Da Capo. ISBN 1-58097-050-8.

- Griffith, Samuel B. (1963). The Battle for Guadalcanal. Champaign, Illinois, US: University of Illinois Press. ISBN 0-252-06891-2.

- Hammel, Eric (1999). Carrier Clash: The Invasion of Guadalcanal & The Battle of the Eastern Solomons August 1942. St. Paul, MN, USA: Zenith Press. ISBN 0-7603-2052-7.

- Jersey, Stanley Coleman (2008). Hell's Islands: The Untold Story of Guadalcanal. College Station, Texas: Texas A&M University Press. ISBN 978-1-58544-616-2.

- Leckie, Robert (2001). Helmet for My Pillow (reissue ed.). ibooks, Inc. ISBN 1-59687-092-3. First-person account of the battle by a member of the 1st Marine Regiment. The Pacific the HBO miniseries is based in part on Helmet for My Pillow

- Morison, Samuel Eliot (1958). The Struggle for Guadalcanal, August 1942 – February 1943, vol. 5 of History of United States Naval Operations in World War II. Boston: Little, Brown and Company. ISBN 0-316-58305-7.

- Rottman, Gordon L. (2005). Japanese Army in World War II: The South Pacific and New Guinea, 1942–43. Dr. Duncan Anderson (consultant editor). Oxford and New York: Osprey. ISBN 1-84176-870-7.

- Smith, Michael T. (2000). Bloody Ridge: The Battle That Saved Guadalcanal. New York: Pocket. ISBN 0-7434-6321-8.

Further reading

- Bartsch, William H. (2014). Victory Fever on Guadalcanal. Texas A&M University Press. ISBN 978-1623491840.

- Richter, Don (1992). Where the Sun Stood Still: The Untold Story of Sir Jacob Vouza and the Guadalcanal Campaign. Toucan. ISBN 0-9611696-3-X.

- Donahue, James (1942). www.guadalcanaljournal.net

- Tregaskis, Richard (1943). Guadalcanal Diary. Random House. ISBN 0-679-64023-1.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Battle of the Tenaru. |

- Anderson, Charles R. (1993). Guadalcanal. The U.S. Army Campaigns of World War II. United States Army Center of Military History. Retrieved July 9, 2006.

- Cagney, James (2005). "The Battle for Guadalcanal". HistoryAnimated.com. Archived from the original (javascript) on May 26, 2012. Retrieved May 17, 2006.- Interactive animation of the battle

- Chen, C. Peter (2004–2006). "Guadalcanal Campaign". World War II Database. Retrieved May 17, 2006.

- Flahavin, Peter (2004). "Guadalcanal Battle Sites, 1942–2004". Retrieved August 2, 2006.- Web site with many pictures of Guadalcanal battle sites from 1942 and how they look now.

- Hough, Frank O.; Ludwig, Verle E.; Shaw, Henry I., Jr. "Pearl Harbor to Guadalcanal". History of U.S. Marine Corps Operations in World War II. Archived from the original on June 27, 2006. Retrieved May 16, 2006.CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)

- Miller, John Jr. (1995) [1949]. Guadalcanal: The First Offensive. United States Army in World War II. United States Army Center of Military History. Retrieved July 4, 2006.

- Shaw, Henry I. (1992). "First Offensive: The Marine Campaign For Guadalcanal". Marines in World War II Commemorative Series. Archived from the original on June 14, 2006. Retrieved July 25, 2006.

- Zimmerman, John L. (1949). "The Guadalcanal Campaign". Marines in World War II Historical Monograph. Archived from the original on June 19, 2006. Retrieved July 4, 2006.