Siege of Bihać (1592)

The Siege of Bihać (Croatian: Opsada Bihaća) was the besieging and capture of the city of Bihać, Kingdom of Croatia within Habsburg Monarchy, by the Ottoman Empire in June 1592. With the arrival of Telli Hasan Pasha as the Beylerbey of the Bosnia Eyalet in 1591, a period of peace established between Emperor Rudolf II and Sultan Murad III ended and the provincial Ottoman armies launched an offensive on Croatia. Bihać, a nearly isolated city on the Una River that repelled an Ottoman attack in 1585, was one of the first targets. Thomas Erdődy, the Ban of Croatia, used available resources and soldiers to protect the border towns, but the Ottomans managed to take several smaller forts in 1591. As the offensive gained pace, the Croatian Parliament passed a law on a general uprising in the country on 5 January 1592.

| Siege of Bihać | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the Ottoman wars in Europe Ottoman–Croatian Wars | |||||||||

Bihać around 1590 | |||||||||

| |||||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||||

|

|

| ||||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||||

| Telli Hasan Pasha |

Joseph Lamberg | ||||||||

| Strength | |||||||||

| 5,000[1] soldiers | 400[2]-500[3] soldiers | ||||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||||

|

2,000 civilians killed 800 civilians taken captive[3] | |||||||||

In early June 1592 Hasan Pasha led his troops towards Bihać, which was defended by around 500 soldiers and commanded by Captain Joseph von Lamberg. The siege lasted from 10 June to 19 June, when Lamberg surrendered the city due to a lack of reinforcements and an insufficient number of defending troops. Lamberg was for this act later tried for treason. Although under the terms of the surrender its citizens were to be allowed to leave or remain in the city without harm, more than 2,000 civilians were killed and 800 were taken captive after Hasan Pasha's troops entered Bihać. The offensive lasted until June 1593 when Hasan Pasha was killed in the Battle of Sisak, which was the cause for the Long Turkish War (1593-1606).

Background

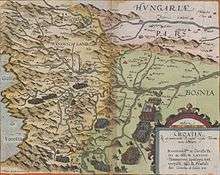

From the 1520s the Ottoman advance into Croatia gained pace. The Croatian nobles elected Ferdinand I of Habsburg at the Parliament on Cetin in 1527 as the new monarch, but continuous Ottoman incursions resulted in a significant loss of territory. In 1537 the fall of Klis meant the loss of the last Croatian stronghold in the south of the country. In the 1540s the Ottomans advanced into Slavonia and in the next three decades through western Bosnia in the direction of Zagreb.[4] By the late 16th century Croatia lost two thirds of its pre-war area and more than half of the population. It was reduced to 16,800 km² of free territory and had around 400,000 inhabitants. The remaining land was referred to as the "remnants of remnants of the once great and renowned Kingdom of Croatia" (Latin: reliquiae reliquiarum olim magni et inclyti regni Croatiae).[5][6]

Numerous ceasefires were signed or renewed between the Ottoman Empire and the Habsburg Monarchy, but they were not respected by local Sanjak-beys. Depending on the weather conditions and available military forces they conducted raids without taking into account a truce.[7] Uskoks, irregular soldiers in Croatia, responded with their own raids into Ottoman held territory.[8] Ottoman authorities settled Vlachs, mainly of Orthodox faith, on the conquered territory and used them as auxiliary units in their wars.[5]

In 1578 Archduke Charles II decided to respond to Ottoman attacks with an offensive to push the frontier back to the Una River.[9] The offensive began in August and the joint Austrian-Croatian troops took back Cazin, Zrin, and Ostrovica, but they were stopped at Bužim and pushed back to the north, losing all gains. Bihać remained basically isolated on the Una River.[10] To strengthen the southern defences the construction of Karlovac as a city-fortress began in 1579.[11] The string of garrisoned forts at the border became known as the Croatian Military Frontier.[4]

The role of Bihać

Following the fall of Knin in 1522 Bihać took the leading role in the Kingdom of Croatia south of the Sava River.[12] It became an important stronghold that protected the area from the Croatian Littoral to the lands around the Una River. From the times of King Matthias Corvinus a garrison was stationed in the city.[13] In 1528[14] Bihać became a center of a captaincy due to its position near the border with the Ottoman Empire and a relatively large number of residents. There were 25 forts under the command of the Bihać Captain in 1576. However, the number of forts was reduced to only three by 1579: Ripač, Sokol and Izačić. The rest were either conquered by the Ottomans or were included into the Slunj captaincy.[15] By the 1580s the city was in a dire state. It was almost surrounded by Ottoman territory, villages in its vicinity were abandoned and there were frequent reports of food shortages. Many of its citizens fled the city and there was a large influx of refugees into Bihać from nearby places that were conquered by the Ottomans.[16]

1585 siege and aftermath

In 1584 the Ottomans suffered a heavy defeat in the Battle of Slunj against the forces of Ban Erdődy. This defeat calmed the situation on the border as Ottoman commanders put a halt on their raids. Erdődy used that time to strengthen the border fortifications and called a session of the Croatian Parliament on 11 March 1585. A decision was made to complete the work on Fort Brest near Sisak and the construction of a new tower in Šišinec on the Kupa River.[17][18]

As the country was affected by a drought in summer, the rivers were drained which made it easier for Ottoman forces to cross into Croatian territory.[17] Ferhad Pasha Sokolović, Beylerbey of the Bosnia Eyalet, prepared an army for an attack on Bihać and its surrounding forts. On 14 September 1585 Ferhad Pasha besieged Bihać, but did not have enough infantryman at his disposal. The defenders of the town, commanded by Captain Franz Horner, used their artillery and inflicted heavy losses to the Ottomans, forcing Ferhad Pasha to lift the siege on the following day. The Ottomans burned several nearby villages during their departure.[19][20]

Local sanjakbeys then turned north and started attacking forts in Slavonia. Ali-beg, Sanjakbey of the Sanjak of Pakrac, was killed in the Battle of Ivanić in 1586. Following an Ottoman defeat near Nagykanizsa in 1587, a relatively lengthy period of peace began on the border. There were no clashes in 1588 and 1589, besides an unsuccessful Ottoman attack on Senj. On 29 November 1590 a truce was renewed between Emperor Rudolf II and Sultan Murad III.[21]

Reneval of hostilities

Contrary to an agreement to extend the truce, with the arrival of belligerent Telli Hasan Pasha (Hasan Pasha Predojević) as the beylerbey of the Eyalet of Bosnia in early 1591, tensions once again increased along the border between Croatia and the Ottoman Empire. Hasan Pasha immediately began to gather an army around Banja Luka and prepared for an offensive on Croatia. Croatian Ban Thomas Erdődy expected attacks on Bihać and Sisak. Discussing about the situation at a session of the Croatian Parliament on 26 July 1591, the nobles concluded that in the case of a large scale invasion, a general uprising was to be called, and that all the nobles and citizens, as well as their subordinates, should answer the call.[22] On 1 August 1591 Hasan Pasha attacked Sisak. The city's position was crucial as it defended the left bank of the Kupa River, but also the approach to Zagreb. Upon hearing of the siege of Sisak, Ban Thomas Erdődy sent help to the city and Hasan Pasha was forced to retreat on 11 August. Erdődy then led a counterattack and took back the town of Moslavina on 12 August.[23][24] This angered Hasan Pasha and he requested the High Porte to cancel the truce and declare a war on the Habsburg Monarchy. He ordered the imprisonment of commanders that surrendered Moslavina and sent them to Istanbul.[25] In November the Ottomans captured Ripač on the Una River, south of Bihać.[26]

On 5 January 1592 the Croatian Parliament passed a law on a general uprising for the defence of the homeland.[24] Nobility, small landowners, military nobility (armalists) and citizens were obliged to report to the ban's camp or risk losing all lands and property. The nobility had to equip and arm two infantryman and one cavalryman for every ten households, while richer merchants had to equip one cavalryman. All royal and free cities had to ensure wagons and carts to transport weapons and ammunition. The law also regulated mandatory provision of food from serfs for the army, which was stored in Zagreb.[27]

Prelude

After an unsuccessful siege of Sisak, the Ottomans were preparing to capture a stronghold near Sisak and make it a base for their further incursions into Croatia.[28] On 14 April Hasan Pasha started building the fort of Petrinja south of Brest.[29] Material for its construction was prepared in advance and the fort was finished on 2 May.[30] As he expected an attack on Bihać, Captain Krištof Obričan ordered the strengthening of city's defences in spring, but he was soon captured by the Ottomans while he supervised the work outside the city walls. Captain Josip Dornberg was appointed in his place, but as he was absent the command was temporarily given to Captain Joseph von Lamberg. At Lamberg's request, reinforcements numbering a hundred Uskoks arrived from Karlovac with food and ammunition. These were the last reinforcements Bihać received.[1]

Siege

In early June, Hasan Pasha raised an army and headed to Bihać with 5,000 soldiers and a large number of cannons.[1] The first part of the Ottoman troops arrived near Bihać on 10 June and encamped at the Pokoj hill north of it. Three days later the main army arrived led by Hasan Pasha and started encircling Bihać. Hasan Pasha detached a part of them to capture Izačić, the last remaining Christian-held settlement between Bihać and the Korana River. Izačić was defended by Gašpar Babonozić who had 16 soldiers at his disposal. They held out the first attack, but left the town on 14 June and fled to Slunj.[2]

The Bihać garrison was commanded by Captain Joseph Lamberg. The garrison numbered between 400 and 500 soldiers, mostly regular Croatian soldiers, Uskoks and German mercenaries, as well as several hundred militiamen.[2][30] Around 5,000 civilians were located in the city. Lamberg sent a letter to Colonel Andreas von Auersperg on 12 June asking for military aid.[2] He sent another letter to Auersperg on 13 June and rejected Hasan Pasha's demand for the surrender of the city. Auersperg's deputy, Captain Juraj Paradeiser, feared for the safety of Karlovac and therefore did not send help. He forwarded the request to the Carniolian nobles, however they did not believe that the threat to Bihać was serious.[31] To keep the morale of his troops and Bihać's citizens, Lamberg organized a public oath on 13 June where they pledged to defend the city to the last man.[32]

By the end of 13 June Bihać was completely surrounded and Lamberg could not send couriers past the Ottoman lines. Hasan Pasha organized his artillery into three groups and deployed it around Bihać, so they were able to shell it from all directions.[31][32] The bombardment of the city began on 14 June, which could be heard in Slunj 25 miles (40 km) away.[31] The first phase of it did not cause significant damage to the walls,[32] but the sheer number of cannons and the lack of reinforcements caused fear in the city and the loss of hope in the possibility of its defence.[30] On 19 June Hasan Pasha ordered an infantry assault on the fortress. As the first siege ladders reached the walls, Bihać's judges and councilors asked Lamberg to start negotiations with Hasan Pasha, saying that the defenders were too weak to withstand the assault and there were no reinforcements. Lamberg was compelled to negotiate an honourable surrender and together with three judges went to Hasan Pasha's tent. Ottoman conditions were an immediate surrender of Bihać, but they assured that its citizens would be allowed to leave with their property or remain and acknowledge Ottoman rule. Lamberg agreed to it and on the same day Ottoman forces entered Bihać.[32][31]

Sack of the city

_-_Muhamed_Ibrahim_Bo%C5%A1ko_(Bosch)_Ramon.jpg)

Lamberg, his soldiers and their families were escorted by several hundred cavalrymen towards Slunj. When the column moved away from the city, the Ottomans started looting them and killed most of the refugees. Only Lamberg and several men managed to flee and reach Brest. Lamberg and the surviving defenders were later tried by court-martial for surrendering Bihać. A majority of the population was reluctant to leave their homes and decided to stay in Bihać. However, Hasan Pasha did not hold up his end of the deal and the city was sacked. In the first days following the capture more than 2,000 citizens were killed, while 800 children were taken captive and sent to Istanbul.[33][34] A contemporary news article (Zeitung) from Vienna about the battle reported that 5,000 Christians were killed.[35][36]

Aftermath and legacy

.jpg)

Together with captives from the Battle of Brest, the prisoners from Bihać were taken to Istanbul, where a triumphant celebration was held in honour of the victory. Wagons were carrying 172 captives and 22 flags captured in Brest and Bihać to the High Porte. Hasan Pasha also sent paintings of Bihać and Slunj to the Sultan, though he did not manage to seize Slunj. The Habsburg imperial envoy in Istanbul protested for the cruelty of Hasan Pasha's forces and in the name of the Emperor asked for the return of Bihać. The Ottomans responded that "every reasonable person can figure out that Bihać can not be returned", as a mosque was already built in it and prayers for the Padishah were held.[37]

The fall of Bihać caused fear in Croatia as it stood on the border for decades.[34] It was the last Croatian stronghold in the south and with its fall the defensive line moved north and extended from Ogulin, through Karlovac and along the Kupa River to Sisak.[28] During its spring-summer offensive of 1592, the Ottoman Empire seized Bihać and Ripač on the Una River, and Dreznik, Floriana and Cetingrad on the Korana River. Thus the Ottomans rounded the area around Bihać and made it the starting point of their further offensives.[38] The town of Karlovac assumed the role of Bihać as the most important fort on the border.[39] Pope Clement VIII, who was elected Pope in February of the same year, was distressed after hearing news of the fall of Bihać. He proposed a league against the Ottoman Empire, but it was rejected by the Signoria of Venice. From July to October 1592 the raids of Hasan Pasha into Bohemia, Croatia and Hungary resulted in the capture of 35,000 people.[35]

A month after the fall of Bihać, on 19 July the Ottomans defeated the forces of Ban Erdődy in the Battle of Brest.[40] In 1593 Hasan Pasha directed his forces towards Sisak, where he suffered a heavy defeat on 22 June and was killed in action. The Battle of Sisak triggered the Long War that lasted until the Peace of Zsitvatorok on 11 November 1606.[41][42]

The Church of Saint Anthony of Padua was converted to a mosque and renamed to Fethija, meaning conquered. It is notable for containing the epitaphs and graves of the Croatian noblemen who died protecting the city.[43] The Ottoman-held area from Velika Kladuša in the west to Vrbas River in the east became known as Turkish Croatia.[44][45]

Footnotes

- Lopašić 1890, p. 87.

- Klaić 1973, p. 478.

- Horvat 1924, chapter 75.

- Tanner 2001, p. 37.

- Mažuran 1998, p. 4.

- Goldstein 1994, p. 30.

- Mažuran 1998, p. 127.

- Mažuran 1998, p. 99.

- Mažuran 1998, p. 131.

- Guldescu 1970, p. 90.

- Guldescu 1970, p. 91.

- Mažuran 1998, p. 48.

- Lopašić 1890, p. 60.

- Lopašić 1890, p. 63.

- Budak 1989, p. 166.

- Budak 1989, pp. 167-168.

- Mažuran 1998, p. 138.

- Klaić 1973, p. 449.

- Mažuran 1998, p. 139.

- Klaić 1973, p. 450.

- Mažuran 1998, pp. 139-141.

- Mažuran 1998, p. 141.

- Mažuran 1998, pp. 141-142.

- Šišić 2004, p. 305.

- Lopašić 1890, p. 86.

- Lopašić 1890, p. 268.

- Mažuran 1998, p. 142.

- Šišić 2004, p. 306.

- Klaić 1973, p. 474.

- Mažuran 1998, p. 143.

- Klaić 1973, p. 479.

- Lopašić 1890, p. 88.

- Lopašić 1890, p. 91.

- Klaić 1973, p. 480.

- Setton 1991, p. 6.

- Ó hAnnracháin 2015, p. 143.

- Lopašić 1890, pp. 91-92.

- Kozličić 2003, p. 135.

- Kozličić 2003, p. 119.

- Mažuran 1998, p. 144.

- Guldescu 1970, p. 96.

- Setton 1991, p. 8.

- Fethija džamija sa haremom, devet grobnih ploča i natpisima, graditeljska cjelina – Članak. Komisija za očuvanje nacionalnih spomenika. (10. novembar 2013.)

- Kozličić 2003, p. 71.

- Tanner 2001, p. 42.

References

- Budak, Neven (1989). "Uloga bihaćke komune u obrani granice" [The role of the community of Bihac in the defence of the border] (PDF). Historijski zbornik. Zagreb: Savez povijesnih društava Hrvatske / Štamparski zavod "Ognjen Prica". 42: 163–170.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Goldstein, Ivo (1994). Sisačka bitka 1593 [Battle of Sisak 1593] (in Croatian). Zagreb: Zavod za hrvatsku povijest Filozofskoga fakulteta Sveučilišta u Zagrebu.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Guldescu, Stanko (1970). The Croatian-Slavonian Kingdom: 1526–1792. The Hague: Walter de Gruyter GmbH & Co KG. ISBN 9783110881622.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Horvat, Rudolf (1924). Povijest Hrvatske: od najstarijeg doba do g. 1657 [History of Croatia: from the earliest times to 1657] (in Croatian). 1. Zagreb: Tiskara Merkur.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Klaić, Vjekoslav (1973). Povijest Hrvata od najstarijih vremena do svršetka XIX. stoljeća [History of Croats from the earliest times to end of 19th century] (in Croatian). 5. Zagreb: Nakladni zavod Matice hrvatske.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Kozličić, Mithad (2003). Unsko-sansko područje na starim geografskim kartama [The Region of Una-Sana on the Old Geographic Charts] (in Croatian). Sarajevo ; Bihać: Nacionalna i univerzitetska biblioteka Bosne i Hercegovine ; Arhiv Unsko-sanskog kantona. ISBN 9958-500-22-1.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Lopašić, Radoslav (1890). Bihać i Bihaćka krajina: mjestopisne i poviestne crtice sa jednom zemljopisnom kartom i sa četrnaest slika (in Croatian). Zagreb: Marjan tisak.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Mažuran, Ive (1998). Povijest Hrvatske od 15. stoljeća do 18. stoljeća [History of Croatia from the 15th to the 18th century] (in Croatian). Zagreb: Golden marketing.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Ó hAnnracháin, Tadhg (2015). Catholic Europe, 1592-1648: Centre and Peripheries. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-927272-3.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Setton, Kenneth Meyer (1991). Venice, Austria, and the Turks in the Seventeenth Century. Philadelphia, Mass.: The American Philosophical Society. ISBN 0-87169-192-2. ISSN 0065-9738.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Šišić, Ferdo (2004). Povijest Hrvata: pregled povijesti hrvatskoga naroda [History of Croats: Overview of the History of the Croatian People] (in Croatian). Zagreb: Marjan tisak. ISBN 9789532141962.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Tanner, Marcus (2001). Croatia: A Nation Forged in War. New Haven: Yale University Press. ISBN 978-0-300-09125-0.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)