Battle of Fort Stevens

The Battle of Fort Stevens was an American Civil War battle fought July 11–12, 1864, in what is now Northwest Washington, D.C., as part of the Valley Campaigns of 1864 between forces under Confederate Lieutenant General Jubal Early and Union Major General Alexander McDowell McCook. Although Early caused consternation in the Union government, reinforcements under Maj. Gen. Horatio G. Wright and the strong defenses of Fort Stevens minimized the military threat and Early withdrew after two days of skirmishing without attempting any serious assaults. The battle is noted for stories that President Abraham Lincoln observed the fighting.

| Battle of Fort Stevens | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the American Civil War | |||||||

.jpg) Officers and men of Company F, 3rd Massachusetts Heavy Artillery, in Fort Stevens | |||||||

| |||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

|

|

| ||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

|

Alexander M. McCook Horatio G. Wright Abraham Lincoln (observer) | Jubal Early | ||||||

| Strength | |||||||

| 9,600[1] | 10,000[2] | ||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||

| 373[3] | 400–500[3][4] | ||||||

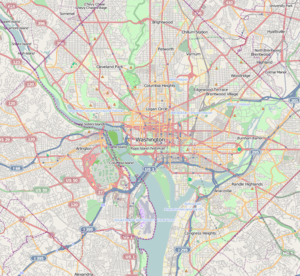

Battle of Fort Stevens location  Battle of Fort Stevens (Maryland)  Battle of Fort Stevens (the United States) | |||||||

Background

In June 1864, Lt. Gen. Jubal Early was dispatched by Gen. Robert E. Lee with the Second Corps of the Army of Northern Virginia from the Confederate lines around Richmond with orders to clear the Shenandoah Valley of Federals and then if practical, invade Maryland, disrupt the Baltimore and Ohio Railroad and if possible threaten Washington, D.C. The hope was that a movement into Maryland would force Union Lt. Gen. Ulysses S. Grant to send troops to defend Washington against the threat, thus reducing his strength to take the Confederate capital of Richmond, Virginia.[5]

After driving off the Army of West Virginia under Maj. Gen. David Hunter after the Battle of Lynchburg on June 18, the Second Corps marched northward through the valley, entering Maryland on July 5 near Sharpsburg. They then turned east towards Frederick where they arrived on July 7. Two days later, as the Second Corps prepared to march on Washington, Maj. Gen. Lew Wallace, leading a small Union force composed mostly of garrison troops, bolstered by the eleventh-hour addition of two brigades of the VI Corps sent from Richmond under Maj. Gen. James B. Ricketts, attempted to resist the Confederate advance at the Battle of Monocacy.[6]

The battle lasted from about 6 a.m. until around 4 p.m, but ultimately Early's corps drove off the small Union force, which was the only substantial Union army between it and the capital. Despite the Union loss, the battle cost General Early precious time better spent advancing the forty miles toward Washington.[7] After the battle Early resumed his march on Washington, arriving at its northeast border near Silver Spring at around noontime on July 11. Because of the battle and then the long march through stifling summer heat, and unsure of the strength of the Federal position in front of him, Early decided not to send his army against the fortifications around Washington until the next day.[8]

Early's invasion of Maryland had the desired effect on Grant, who dispatched the rest of the VI Corps and XIX Corps under Maj. Gen. Horatio G. Wright to Washington on July 9. Lee later wrote to Secretary of War James Seddon on July 19 that,

It was believed that the Valley could then be effectually freed from the presence of the enemy and it was hoped that by threatening Washington and Baltimore, Gen. Grant would be compelled to weaken himself so much for their protection as to afford an opportunity to attack him, or that he might be induced to attack us.[9]

The steamers carrying the Union force started to arrive in southeast Washington around noon on July 11, at about the same time that Early himself had reached the outskirts of Fort Stevens with the lead elements of his troops.[10]

Defense of Washington

The city of Washington, D.C. prepared for the Confederate assault in the midst of one of the worst hot spells in its history, lasting 47 days without rain with temperatures exceeding 90 °F (32.2 °C). The Congress and prominent residents left town to escape the heat as much as the impending Confederate advance.[11] However, President Lincoln remained near the city, staying with his family at the Soldier's Home in present-day Northwest Washington, but a steamer waited on the Potomac to evacuate them if the situation became dire.[12] Meanwhile, refugees from surrounding counties began to enter the relative safety of the city.

Overall command for defense of the District was given to Major General Christopher C. Augur as commander of the XXII Corps. Major Generals Quincy Gillmore and Alexander McCook commanded the Northeast sector and the reserve post at Blagden Farm, respectively. Augur commanded 31,000 troops and 1,000 artillery pieces in 160 fortifications, batteries, and trenches.[13] Eighty-seven fortifications were located north of the Potomac (facing Early's approach) with 484 heavy guns and 13,986 men. Land was cleared surrounding the city to create open fields of fire. Six companies of the 8th Illinois Cavalry were stationed in front of the northern defenses.[13]

Despite this impressive array, Washington was in truth lacking in its defensive capabilities. General John G. Barnard, Grant's engineering officer, noted that many of the troops were not actually fit for duty as many were new recruits, untried reserves, men recovering from wounds, or worn-out veterans. Bernard estimated that instead of 31,000, the actual number of usable troops was around 9,600.[14] The capital was more vulnerable to Confederate attack than it seemed: with around 10,000 troops, the Confederate army matched the effective Union troop strength.

Union command structure

The arrival of the VI Corps, approximately 10,000 men, brought desperately needed veteran reinforcements. It also added another high-ranking officer into a jumbled Federal command. The Washington defenses played host to a number of generals ejected from major theaters of the war or incapacitated for field command due to wounds or disease. Maj. Gen. Alexander M. McCook was one of the former, having not held a command since being relieved of command after the Battle of Chickamauga. McCook was, however, placed in command of the Defenses of the Potomac River & Washington, superseding Christopher Columbus Augur, who commanded the Department of Washington. Augur also commanded the XXII Corps, whose troops manned the capital's defensive works. Maj. Gen. Henry W. Halleck called upon Maj. Gen. Quincy A. Gillmore in New York City to take command of a detachment from the XIX Corps. The U.S. Army's Quartermaster General, Brig. Gen. Montgomery C. Meigs, took command of an "Emergency Division", composed of federal employees who were armed during the raid, directly under the command of McCook. Even President Abraham Lincoln personally arrived at the battlefield. McCook tried to sort out the problem of too many high-ranking generals in the face of Early's advance. He was unable to rid himself of the generals, and their attempts to gain leverage over one another, but a somewhat workable command structure was established. With McCook in overall command, Gillmore commanded the northeast line of fortresses (Fort Lincoln to Fort Totten), Meigs commanded the northern line of forts (Fort Totten to Fort DeRussy—including Fort Stevens) and Augur's First Division commander, Martin D. Hardin, commanded the northwest line of forts (Fort DeRussy to Fort Sumner). Wright and the VI Corps were initially to be held in reserve but McCook immediately decided against this, stating that he felt veteran troops needed to take the front lines against Early's troops. As it was, Hardin's troops engaged in some light skirmishing, but as McCook intended, it was to be Wright's veterans who bore the brunt of the fighting.[15]

Opposing forces

Union

Confederate

Battle

At about the time Wright's command was arriving in Washington, Early's corps began to arrive at the breastworks of Fort Stevens, yet Early delayed the attack because he was still unsure of the federal strength defending the fort, much of his army was still in transit to the front, and the troops he had were exhausted due to the excessive heat and the fact that they had been on the march since June 13. Additionally, many of the Confederate troops had looted the home of Montgomery Blair, the son of the founder of Silver Spring, Maryland. They found barrels of whiskey in the basement of the mansion, called Blair Mansion, and many troops were too drunk to get a good start in the morning. This allowed for further fortification by Union troops.[16]

Around 3 p.m., with the bulk of their force present, the Confederates commenced skirmishing, probing the defense maintained by Brig. Gen. Martin D. Hardin's division of the XXII Corps with a line of skirmishers backed by artillery. Near the start of the Confederate attack the lead elements of the VI and XIX Corps arrived at the fort, reinforcing it with battle-hardened troops. The battle picked up around 5 p.m. when Confederate cavalry pushed through the advance Union picket line. A Union counterattack drove back the Confederate cavalry and the two opposing lines confronted each other throughout the evening with periods of intense skirmishing. The Union front was aided by artillery from the fort, which shelled Confederate positions, destroying many houses that Confederate sharpshooters used for protection.[17]

President Lincoln, his wife Mary, and some officers rode out to observe the attack, either on July 11 or July 12, and were briefly under enemy fire that wounded a Union surgeon standing next to Lincoln on the Fort Stevens parapet. Lincoln was brusquely ordered to take cover by an officer, possibly Horatio Wright, although other probably apocryphal stories claim that it was Oliver Wendell Holmes, Jr., Private John A. Bedient of the 150th Ohio Infantry, the fort commander, other privates of the Ohio National Guard, and Elizabeth Thomas.[18][19][20][21]

Additional Union reinforcements from the VI and XIX Corps arrived overnight and were placed in reserve behind the line. The skirmishing continued into July 12, when Early finally decided that Washington could not be taken without heavy losses which would be too severe to warrant the attempt. Union artillery from Fort Stevens attempted to clear out Confederate sharpshooters hidden in the buildings and fields in front of the fort; when the artillery fire failed to drive them off, the VI Corps brigade of Daniel Bidwell, supported by Oliver Edwards' brigade and two Veteran Reserve Corps regiments, attacked at about 5 p.m. The attack was successful, but at the cost of over 300 men.[22]

Aftermath

Early's force withdrew that evening, headed back into Montgomery County, Maryland, and crossed the Potomac River on July 13 at White's Ferry into Leesburg, Virginia. The Confederates successfully brought the supplies they seized during the previous weeks with them into Virginia. Early remarked to one of his officers after the battle, "Major, we didn't take Washington but we scared Abe Lincoln like hell."[23] Wright organized a pursuit force and set out after them during the afternoon of the 13th.[24]

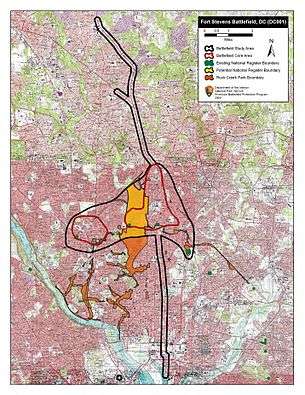

Battlefield

Fort Stevens is now maintained by the National Park Service under the administration of the Civil War Defenses of Washington. The fort is located near 13th Street NW between Rittenhouse and Quackenbos Streets NW and is the only part of the battlefield currently preserved; the remainder was developed following 1925. The Battleground National Cemetery was established two weeks after the battle and is located nearby, at 6625 Georgia Avenue NW, containing the graves of forty Union soldiers killed in the battle; seventeen Confederate soldiers are buried on the grounds of Grace Episcopal Church, slightly north of current downtown Silver Spring, Maryland at the intersection of Georgia Avenue and Grace Church Road.[25]

See also

References

- Cooling 1989, pp. 278-279.

- Bernstein 2011, p. 70.

- Kennedy 1998, p. 309.

- Cooling 1989, p. 151.

- Cooling 1989, pp. 8-11.

- Cooling 1989, pp. 11-14, 40, 57, 57-61.

- Judge 1994, p. 201.

- Bernstein 2011, pp. 45-55.

- Alvord 1897, p. 32.

- Cooling 1989, pp. 38, 86, 104.

- Judge 1994, p. 216.

- Judge 1994, p. 217.

- Judge 1994, p. 218.

- Judge 1994, p. 219.

- Cooling 1989, pp. 97-102, 127.

- Cooling 1989, pp. 117, 123.

- Bernstein 2011, pp. 68-69.

- Bernstein 2011, pp. 73-74.

- Cooling 1989, pp. 142-143.

- Cramer 1948, pp. 91-93.

- Some local newspaper articles do not mention the incident. An article about the battle published in the Washington Evening Star on July 12, 1864, made no mention of President Lincoln at the battlefield. ("The Invasion: The Condition of Things Last Night - The Fighting out the Seventh Street Road - Rebel Sharpshooters Dislodged - The Enemy Attempt to Plant a Battery, but are Shelled Away - Policemen and Other Citizens Take a Hand in the Fighting". The Washington Evening Star. July 12, 1864.) The article in the July 13, 1864, edition mentioned that "President Lincoln and Mrs. Lincoln passed along the line of the city defences in a carriage last night, and were warmly greeted by the soldiers wherever they made their appearance amongst them." but the article made no mention of President Lincoln actually coming under fire. ("The Invasion: Late and Important: The Rebels Have Disappeared From Our Front! They Leave Their Dead and Wounded Behind Them!". The Washington Evening Star. July 13, 1864. p. 2.).

- Cooling 1989, pp. 127, 136-138, 145-150.

- Vandiver 1988, p. 171.

- Cooling 1989, pp. 184-187.

- Cooling 1989, pp. 237-238, 245.

Bibliography

- National National Park Service battle description

- Alvord, Henry E. (1897). Early's Attack upon Washington, July 1864. Washington, D.C.: Military Order of the United States, Commander of the District of Columbia.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Bernstein, Steven (2011). The Confederacy's Last Northern Offensive: Jubal Early, the Army of the Valley and the Raid on Washington. Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland & Company, Inc. ISBN 978-0-7864-5861-5.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Cooling, Benjamin F. (1989). Jubal Early's Raid on Washington 1864. Baltimore, Maryland: Rockbridge Publishing Company. ISBN 0-933852-86-X.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Cramer, John Henry (1948). Under Enemy Fire: The Complete Account of His Experiences During Early's Attack on Washington. Baton Rouge, Louisiana: Louisiana State University Press. ISBN 978-0-5983-6703-7.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Judge, Joseph (1994). Season of Fire: The Confederate Strike on Washington. Berryville, Virginia: Rockbridge Publishing Company. ISBN 1-883522-00-5.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Kennedy, Francis H. (1998). The Civil War Battlefield Guide. Boston, Massachusetts: Houghton Mifflin Co. ISBN 0-395-74012-6.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Leepson, Marc. Desperate Engagement: How a Little-Known Civil War Battle Saved Washington D.C., and Changed American History. New York: Thomas Dunne Books (St. Martin's Press), 2005. ISBN 978-0-312-38223-0.

- Vandiver, Frank E. (1988). Jubal's Raid: General Early's Famous Attack on Washington in 1864. Lincoln, Nebraska: University of Nebraska Press. ISBN 978-0-8032-9610-7.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

External links

- The Battle of Fort Stevens: Maps, histories, photos, facts, and preservation news (Civil War Trust)

- Battleground National Cemetery

- National Park Service website for Fort Stevens