Baker Street and Waterloo Railway

The Baker Street and Waterloo Railway (BS&WR), also known as the Bakerloo tube, was a railway company established in 1893 that built a deep-level underground "tube" railway in London.[lower-alpha 1] The company struggled to fund the work, and construction did not begin until 1898. In 1900, work was hit by the financial collapse of its parent company, the London & Globe Finance Corporation, through the fraud of Whitaker Wright, its main shareholder. In 1902, the BS&WR became a subsidiary of the Underground Electric Railways Company of London (UERL) controlled by American financier Charles Yerkes. The UERL quickly raised the funds, mainly from foreign investors.

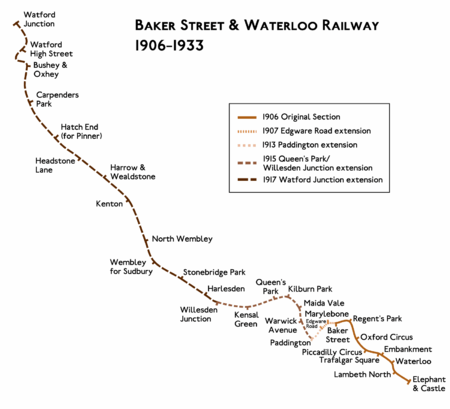

When opened in 1906, the BS&WR's line served nine stations and ran completely underground in a pair of tunnels for 5.81 kilometres (3.61 mi) between its northern terminus at Baker Street and its southern terminus at Elephant and Castle with a depot on a short spur nearby at London Road.[1] Extensions between 1907 and 1913 took the northern end of the line to the terminus of the Great Western Railway (GWR) at Paddington. Between 1915 and 1917, it was further extended to Queen's Park, where it came to the surface and connected with the London and North Western Railway (LNWR), and to Watford; a total distance of 33.34 kilometres (20.72 mi).[1]

Within the first year of opening it became apparent to the management and investors that the estimated passenger numbers for the BS&WR and the other UERL lines were over-optimistic. Despite improved integration and cooperation with the other tube railways and the later extensions, the BS&WR struggled financially. In 1933, the BS&WR was taken into public ownership along with the UERL. Today, the BS&WR's tunnels and stations operate as the London Underground's Bakerloo line.

Establishment

Origin, 1891–93

The idea of building an underground railway along the approximate route of the BS&WR had been put forward well before it came to fruition at the turn of the century. As early as 1865, a proposal was put forward for a Waterloo & Whitehall Railway, powered by pneumatic propulsion. Carriages would have been sucked or blown a distance of three-quarters of a mile (about 1 km) from Great Scotland Yard to Waterloo Station, travelling through wrought-iron tubes laid in a trench at the bottom of the Thames.[2] The scheme was abandoned three years later after a financial panic caused its collapse.[3] Sir William Siemens of Siemens Brothers served as electrical engineer for a later abortive scheme, the Charing Cross & Waterloo Electric Railway. It was incorporated by an Act of Parliament in 1882 and got as far as constructing a 60 feet (18 m) stretch of tunnel under the Victoria Embankment before running out of money.[4]

According to a pamphlet published by the BS&WR in 1906, the idea of constructing the line "originally arose from the desire of a few business men in Westminster to get to and from Lord's Cricket Ground as quickly as possible," to enable them to see the last hour's play without having to leave their offices too early. They realised that an underground railway line connecting the north and south of central London would provide "a long-felt want of transport facilities" and "would therefore prove a great financial success." They were inspired by the recent success of the City and South London Railway (C&SLR), the world's first deep-tube railway, which proved the feasibility of such an endeavour.[5] This opened in November 1890 and carried large numbers of passengers in its first year of operation.[lower-alpha 2]

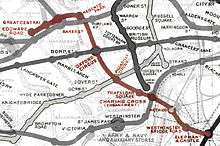

In November 1891, notice was given of a private bill that would be presented to Parliament for the construction of the BS&WR.[7] The railway was planned to run entirely underground from the junction of New Street (now Melcombe Street) and Dorset Square west of Baker Street to James Street (now Spur Road) on the south side of Waterloo station. From Baker Street, the route was to run eastwards beneath Marylebone Road, then curve to the south under Park Crescent and follow Portland Place, Langham Place and Regent Street to Piccadilly Circus. It was then to run under Haymarket, Trafalgar Square and Northumberland Avenue before passing under the River Thames to Waterloo station. A decision had not been made between the use of cable haulage or electric traction as the means of pulling the trains.[7]

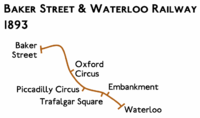

Bills for three similarly inspired new underground railways were also submitted to Parliament for the 1892 parliamentary session, and, to ensure a consistent approach, a Joint Select Committee was established to review the proposals. The committee took evidence on various matters regarding the construction and operation of deep-tube railways, and made recommendations on the diameter of tube tunnels, method of traction, and the granting of wayleaves. After rejecting the construction of stations on land owned by the Crown Estate and the Duke of Portland between Oxford Circus and Baker Street, the Committee allowed the BS&WR bill to proceed for normal parliamentary consideration.[8] The route was approved and the bill received royal assent on 28 March 1893 as the Baker Street and Waterloo Railway Act, 1893.[9] Stations were permitted at Baker Street, Oxford Circus, Piccadilly Circus, Trafalgar Square, Embankment and Waterloo.[8] The depot would have been at the south end of the line at James Street and Lower Marsh.[10]

Search for finance, 1893–1903

Although the company had permission to construct the railway, it still had to raise the capital for the construction works. The BS&WR was not alone; four other new tube railway companies were looking for investors – the Waterloo and City Railway (W&CR), the Charing Cross, Euston and Hampstead Railway (CCE&HR) and the Great Northern and City Railway (GN&CR) (the three other companies that were put forward in bills in 1892) and the Central London Railway (CLR, which received royal assent in 1891).[lower-alpha 3] The original tube railway, the C&SLR, was also raising funds to construct extensions to its existing line.[12] Only the W&CR, which was the shortest line and was backed by the London and South Western Railway with a guaranteed dividend, was able to raise its funds without difficulty. For the BS&WR and the rest, and others that came later, much of the remainder of the decade saw a struggle to find finance in an uninterested market.[13]

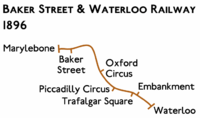

Like most legislation of its kind, the act of 1893 imposed a time limit for the compulsory purchase of land and the raising of capital.[lower-alpha 4] To keep the powers alive, the BS&WR announced a new bill in November 1895,[14] which included an application for an extension of time. The additional time and permission to raise an extra £100,000 of capital was granted when the Baker Street and Waterloo Railway Act, 1896 received royal assent on 7 August 1896.[4][15]

In November 1897, the BS&WR did a deal with the London & Globe Finance Corporation (L&GFC), a mining finance company operated by mining speculator Whitaker Wright and chaired by Lord Dufferin. The L&GFC was to fund and manage the construction, taking any profit from the process.[16] The cost of construction was estimated to be £1,615,000 (equivalent to approximately £183 million today).[17][18] The L&GFC replaced the BS&WR's directors with its own and let construction contracts. Wright made fortunes in America and Britain by promoting gold and silver mines and saw the BS&WR as a way of diversifying the L&GFC's holdings.[16]

In 1899, Wright fraudulently concealed large losses by one of the corporation's mines by manipulating the accounts of various L&GFC subsidiary companies.[16] Expenditure for the BS&WR was also high, with the L&GFC having paid out approximately £650,000 (£70.9 million today) by November 1900. In its prospectus of November 1900, the company forecast that it would realise £260,000 a year from passenger traffic, with working expenses of £100,000, leaving £138,240 for dividends after the deduction of interest payments. [18][19] Only a month later, however, Wright's fraud was discovered and the L&GFC and many of its subsidiaries collapsed.[16] Wright himself subsequently committed suicide by taking cyanide during his trial at the Royal Courts of Justice.[20]

The BS&WR struggled on for a time, funding the construction work by making calls on the unpaid portion of its shares,[16] but activity eventually came to a stop and the partly built tunnels were left derelict.[21] Before its collapse, the L&GFC attempted to sell its interests in the BS&WR for £500,000 to an American consortium headed by Albert L. Johnson, but was unsuccessful. However, it attracted the interest of another American consortium headed by financier Charles Yerkes.[4] After some months of negotiations with the L&GFC's liquidator, Yerkes purchased the company for £360,000 plus interest (£39.4 million today).[18][22] He was involved in the development of Chicago's tramway system in the 1880s and 1890s. He came to London in 1900 and purchased a number of the struggling underground railway companies,[lower-alpha 5] The BS&WR became a subsidiary of the Underground Electric Railways Company of London (UERL) which Yerkes formed to raise funds to build the tube railways and to electrify the District Railway. The UERL was capitalised at £5 million with the majority of shares sold to overseas investors.[lower-alpha 6] Further share issues followed, which raised a total of £18 million by 1903 (equivalent to approximately £1.95 billion today)[18] for use across all of the UERL's projects.[lower-alpha 7]

Planning the route, 1893–1904

BS&WR bill, 1896

While the BS&WR raised money, it continued to develop the plans for its route. The November 1895 bill sought powers to modify the planned route of the tunnels at the Baker Street end of the line and extend them approximately 200 metres (660 ft) beyond their previous end point at the south-eastern corner of Dorset Square to the south-eastern corner of Harewood Square.[14] This area was to be the site of Marylebone station, the new London terminus of the Manchester, Sheffield and Lincolnshire Railway's extension from the Midlands then under construction.[8]Approval for the extension and a new station at Marylebone were included in the Baker Street and Waterloo Railway Act, 1896.[8][15]

New Cross & Waterloo Railway bill, 1898

On 26 November 1897, details of a bill proposed for the 1898 parliamentary session were published by the New Cross and Waterloo Railway (NC&WR), an independent company promoted by James Heath MP, which planned two separate sections of tube line that would connect directly to the BS&WR, extending the line south-east from Waterloo and east from around Marylebone Road.[24][25]

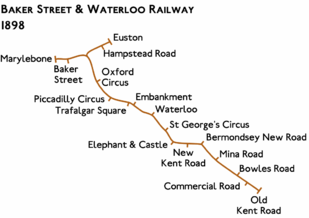

The southern of the NC&WR's two extensions was planned to connect with the BS&WR tunnels under Belvedere Road to the west of Waterloo station and head east under the mainline station to its own station under Sandell Street adjacent to Waterloo East station. The route was then planned to run under Waterloo Road, St George's Circus and London Road to Elephant and Castle. The route then followed New Kent Road and Old Kent Road as far as the London, Brighton and South Coast Railway's Old Kent Road station (closed in 1917). Intermediate stations were to be constructed at St George's Circus, Elephant and Castle (where the NC&WR station would interchange with the C&SLR's station below ground and link to the London, Chatham and Dover Railway's station above ground), in New Kent Road at Munton Road, at the junction of New Kent Road and Old Kent Road, and on Old Kent Road at the junctions with Mina Road, Bowles Road and Commercial Road (now Commercial Way). A power station was planned on the south side of Old Kent Road where it crossed the Grand Surrey Canal (now filled-in) at the junction with St James's Road. This would have provided a delivery route for fuel and a source of water. Tunnels were also planned to connect the BS&WR's proposed depot at Waterloo to the NC&WR's route enabling trains to enter and exit in two directions.[25]

The NC&WR's other planned extension was to branch from the BS&WR's curve under Park Crescent. It was then to curve eastwards under Regent's Park and then run under Longford Street and Drummond Street to end at a station on the west side of Seymour Street (now Eversholt Street) under Euston station. An intermediate station was planned for the junction of Drummond Street and Hampstead Road.[25]

The bill was deposited in Parliament, but no progress was made in the 1898 session and it disappeared afterwards, although the BS&WR presented a modified version of the Euston branch in a bill for the 1899 session.[25][26]

BS&WR bill, 1899

Construction work began in August 1898,[27] although the BS&WR was continuing to develop new route plans. The bill for 1899, published on 22 November 1898, requested more time for the construction works and proposed two extensions to the railway and a modification to part of the previously approved route.[28] The first extension, like the NC&WR's plan from the year before, was to branch from the already-approved route under Park Crescent, but then followed a more northerly route than the NC&WR, running under Regent's Park to cross the park's Outer Circle between Chester Road and Cumberland Gate where a station was to be constructed. The route then followed Cumberland Street West (now Nash Street), Cumberland Market, Cumberland Street East and Edward Street (both now Varndell Street), before ending at a station under Cardington Street on the west side of Euston station.[26]

The second extension was to continue the line west from Marylebone, running under Great James Street and Bell Street (now both Bell Street) to Corlett Street, then turning south to reach the Grand Junction Canal's Paddington Basin to the east of the GWR's Paddington station. A station was to be located directly under the east-west arm of the basin before the line turned north-west, running between the mainline station and the basin, before the two tunnels merged into one. The single tunnel was then to turn north-east, passing under the Regent's Canal to the east of Little Venice, before coming to the surface where a depot was to be built on the north side of Blomfield Road. The BS&WR also planned a power station at Paddington. The final change to the route was a modification at Waterloo to move the last section of the line southwards to end under Addington Street.[26] The aim of these plans was, as the company put it in 1906, "to tap the large traffic of the South London Tramways, and to link up by a direct Line several of the most important Railway termini."[29]

The Metropolitan Railway (MR), London's first underground railway, which operated between Paddington and Euston over the northern section of the Inner Circle since 1863,[lower-alpha 8] saw the BS&WR's two northern extensions as competition for its own service and strongly objected. Parliament accepted the objections; when the Baker Street and Waterloo Railway Act, 1899 received royal assent on 1 August 1899, only the extension of time and the route change at Waterloo were approved[26][30]

BS&WR bill, 1900

In November 1899, the BS&WR announced a bill for the 1900 session.[31] Again, an extension was proposed from Marylebone to Paddington, this time terminating to the east of the mainline station at the junction of Bishop's Road (now Bishop's Bridge Road) and Gloucester Terrace. A station was planned under Bishop's Road, linked to the mainline station by a subway under Eastbourne Terrace. From Waterloo, an extension was planned to run under Westminster Bridge Road and St George's Road to terminate at Elephant and Castle. The BS&WR would connect there with the C&SLR's station as the NC&WR planned two years earlier. A spur was to be provided to a depot and power station that were to be constructed on the site of the School for the Indigent Blind south of St George's Circus.[32]

The Paddington extension was aligned to allow a westward extension to continue to Royal Oak or Willesden, areas already served by the MR, which again opposed the plans.[32] This time, the BS&WR was successful and royal assent for the extensions was granted in the Baker Street and Waterloo Railway Act, 1900 on 6 August 1900.[32][33]

Minor changes, 1902–04

To make up for the time lost following the collapse of the L&GFC and to restore the BS&WR's finances, the company published a bill in November 1901, which sought another extension of time and permission to change its funding arrangements.[34] The bill was approved as the Baker Street and Waterloo Railway Act, 1902 on 18 November 1902.[35]

For the 1903 parliamentary session, the UERL announced bills for the BS&WR and its other tube railways, seeking permission to merge the three companies by transferring the BS&WR's and CCE&HR's powers to the Great Northern, Piccadilly and Brompton Railway (GNP&BR). The BS&WR bill also included requests for a further extension of time and for powers to compulsorily purchase land for an electrical sub-station at Lambeth.[36] The merger was rejected by Parliament,[37] but the land purchase and extension of time were permitted separately in the Baker Street and Waterloo Railway Act, 1903 and the Baker Street and Waterloo Railway (Extension of Time) Act, 1903, both given royal assent on 11 August 1903.[38]

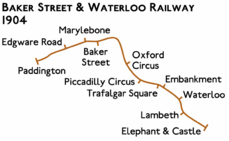

For the 1904 Parliamentary session, the BS&WR bill sought permission to add new stations at Lambeth, Regent's Park and Edgware Road.[39] The new stations were permitted by the Baker Street and Waterloo Railway Act, 1904 given royal assent on 22 July 1904.[40]

Construction, 1898–1906

Construction commenced in the summer of 1898 under the direction of Sir Benjamin Baker (who co-designed the Forth Bridge), W.R. Galbraith and R.F. Church. The works were carried out by Perry & Company of Tregedar Works, Bow.[4]

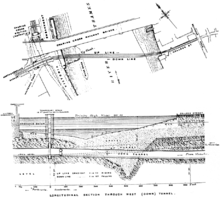

The main construction site was located at a substantial temporary staging pier erected in the River Thames a short distance south of the Hungerford Bridge.[41] It was described at the time as "a small village of workshops and offices and an electrical generating station to provide the power for driving the machinery and for lighting purposes during construction."[29] The 50 feet (15 m) wide stage was located 370 feet (110 m) from the Hungerford Bridge's first pier, 150 feet (46 m) from the north bank of the Thames. It was originally intended that the work should begin close to the south bank, with a bridge connecting the stage to College Street – a now-vanished road on the site of the present-day Jubilee Gardens. However, test borings showed that there was a deep depression in the gravel beneath the Thames, which it was speculated was the result of dredging carried out for the abortive Charing Cross & Waterloo Railway project. This led to the work site being relocated to the north side of the river.[42]

Two caissons were sunk into the river bed below the stage. From there, the tunnels were constructed in each direction using Barlow-Greathead tunnelling shields of a similar design to those used to construct the C&SLR.[29] The north tunnel was constructed first, commencing in February 1899, followed by the south tunnel from March 1900. This was technically the most difficult stage of the project, as it necessitated tunnelling under the river.[43] The tunnellers worked in an atmosphere of compressed air at up to 35 psi (240 kPa) to prevent water leaking into the excavations.[4] On several occasions, however, the tunnel was breached and escaping air caused "blowouts", producing water spouts up to 2.5 feet (0.76 m) high above the surface of the river. One such blowout disrupted Doggett's Coat and Badge race.[43] By using the river as the centre of tunnelling operations, the company was able to remove excavated soil onto barges and bring in required material the same way, thus avoiding having to transport large amounts of material through the streets.[29] Tunnelling also took place from station sites, notably at Piccadilly Circus. The tunnellers worked with a remarkable degree of accuracy given the technology of the time; the tunnel being driven north from the Thames eventually reached the one being dug south from Piccadilly Circus, meeting under Haymarket, with a deviation of only three-quarters of an inch (1.9 cm).[44]

The tunnel linings were formed from cast iron segments 7⁄8 inch (2.22 cm) thick, which locked together to form a ring with an internal diameter of 12 feet (3.66 m). Once a ring was completed, grout was injected through holes in the segments to fill any voids between the outside edge of the ring and the excavated ground beyond, reducing subsidence.[8] By November 1899 the northbound tunnel reached Trafalgar Square and work on some of the station sites was started, but the collapse of the L&GFC in 1900 led to works gradually coming to a halt. When the UERL was constituted in April 1902, 50 per cent of the tunnelling and 25 per cent of the station work was completed.[45] With funds in place, work restarted and proceeded at a rate of 73 feet (22.25 m) per week,[21] so that by February 1904 virtually all of the tunnels and underground parts of the stations between Elephant & Castle and Marylebone were complete and works on the station buildings were under way.[46] The additional stations were incorporated as work continued elsewhere and Oxford Circus station was altered below ground following a Board of Trade inspection; at the end of 1905, the first test trains began running.[47] Although the BS&WR had permission to continue to Paddington, no work was undertaken beyond Edgware Road.[48]

The BS&WR used a Westinghouse automatic signalling system operated through electric track circuits. This controlled signals based on the presence or absence of a train on the track ahead. Signals incorporated an arm that was raised when the signal was red. If a train failed to stop at a red signal, the arm activated a "tripcock" on the train, applying the brakes automatically.[49]

Stations were provided with surface buildings designed by architect Leslie Green in the UERL house-style.[50] This consisted of two-storey steel-framed buildings faced with red glazed terracotta blocks, with wide semi-circular windows on the upper floor.[lower-alpha 9] They were designed with flat roofs to enable additional storeys to be constructed for commercial occupants, maximising the air rights of the property.[51] Except for Embankment, which had a sloping passageway down to the platforms, each station was provided with between two and four lifts and an emergency spiral staircase in a separate shaft.[lower-alpha 10] At platform level, the wall tiling featured the station name and an individual geometric pattern and colour scheme designed by Green.[55]

Oxford Circus station, an example of the Leslie Green design used for most of the BS&WR's stations

Oxford Circus station, an example of the Leslie Green design used for most of the BS&WR's stations An original 1907 ticket office window at Edgware Road tube station (Bakerloo line)

An original 1907 ticket office window at Edgware Road tube station (Bakerloo line) Wall tiling at Regent's Park tube station showing the station name and Green's geometric decoration

Wall tiling at Regent's Park tube station showing the station name and Green's geometric decoration

It was originally intended that the electrical supply to the line and stations would be provided by a dedicated generating station at St George's Road, Southwark. This idea was abandoned in 1902 and electricity was instead provided by Lots Road Power Station, operated by the UERL.[4] Six ventilation fans were installed along the line to draw 18,500 cubic feet per minute through the tunnels and out through exhausts placed on the roof of the stations. Fresh air was drawn back down from the surface via the lift and staircase shafts, thus replenishing the air in the tunnels.[56] To reduce the risk of fire, the station platforms were built of concrete and iron and the sleepers were made from the fireproof Australian wood Eucalyptus marginata or jarrah.[57]

The design of the permanent way was a departure from that of London's previous tube railways, which used track laid on timber baulks across the tunnel with the bottom of the tube left open. This approach caused what the BS&WR's management regarded as an unacceptable level of vibrations. They resolved this by mounting the sleepers on supports made of sand and cement grout, with the sleeper ends resting on comparatively soft broken stone ballast underneath the running rails. A drain ran parallel with the rails underneath the middle of the track. The rails themselves were unusually short – only 35 feet (11 m) long – as this was the maximum length that could be brought in through the shafts and then turned horizontally to be carried into the tunnels. Power was supplied through third (positive) and fourth (negative) rails laid in the middle and outside of the track, as used on the District Railway.[4]

Opening

Baker Street & Waterloo Railway | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Extent of Railway at transfer to LPTB, 1933 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Key | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

The official opening of the BS&WR by Sir Edwin Cornwall, chairman of the London County Council, took place on 10 March 1906.[58] Shortly after the line's opening, the London Evening News columnist "Quex"[4] coined the abbreviated name "Baker-loo", which quickly caught on and began to be used officially from July 1906,[59] appearing on contemporary maps of the tube lines.[60] The nickname was, however, deplored by The Railway Magazine, which complained: "Some latitude is allowable, perhaps, to halfpenny papers, in the use of nicknames, but for a railway itself to adopt its gutter title, is not what we expect from a railway company. English railway officers have more dignity than to act in this manner."[4]

The railway had stations at:[61]

The section to Edgware Road was completed and brought into service in two stages:[61]

|

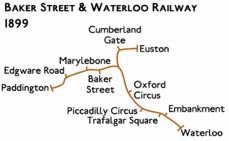

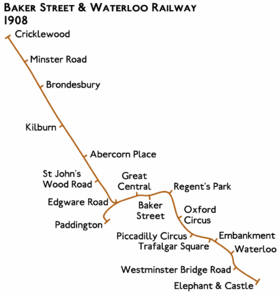

Contemporary map of the Baker Street and Waterloo Railway. The extension to Great Central and Edgware Road stations was opened in 1907. |

While construction was being finished, trains operated out of service beyond Baker Street, reversing at a crossover to the east of the station under construction at Marylebone.[49]

Rolling stock, fares and schedules

The service was provided by a fleet of 108 carriages manufactured for the UERL in the United States by the American Car and Foundry Company and assembled in Manchester.[63] They were transported to London by rail but because the BS&WR had no external railway connections, the carriages then had to be transported across the city on horse-drawn wagons to their destination at London Road depot.[64]

The carriages operated as electric multiple unit trains without separate locomotives.[63] Passengers boarded and left the trains through folding lattice gates at each end of cars; these gates were operated by gate-men who rode on an outside platform and announced station names as trains arrived.[65] The design was subsequently used for the GNP&BR and the CCE&HR, and became known on the Underground as the 1906 stock or Gate stock. Trains for the line were stabled at the London Road depot south of Kennington Road station.[lower-alpha 12]

The line operated from 5:30 am to 12:30 am on weekdays (including Saturdays), and 7:30 am to 12 noon on Sundays.[66] The standard one-way fare following the line's opening was 2d. ("workmen's tickets" at 2d. return were available up to 7:58 am) and a book of 25 tickets was available at 4s. However, the original flat fares were abandoned in July 1906 and replaced with graded fares of between 1d. and 3d.[4] In November 1906, season tickets were introduced along with through tickets with the District Railway (interchanging at Charing Cross). It was not until December 1907 that it was possible to buy a through ticket onto the Central London Railway (via Oxford Circus). The BS&WR abolished its season tickets in October 1908 and replaced them with strip tickets, sold in sets of six, that could be used on the Bakerloo, Piccadilly and Hampstead tubes.[67]

The service frequency as of mid-1906 was as follows:

- Weekdays

- From 5:30 am to 7:30 am: every 5 minutes

- From 7:30 am to 11:30 pm: every 3 minutes

- From 11:30 pm to 12:30 am: every 6 minutes

- Sundays

- From 7:30 am to 11 am: every 6 minutes

- From 11 am to 12 noon: every 3 minutes [66]

Co-operation and consolidation, 1906–10

Despite the UERL's success in financing and constructing the railway, its opening did not bring the financial success that had been expected. In the Bakerloo Tube's first twelve months of operation it carried 20.5 million passengers, less than sixty per cent of the 35 million that had been predicted during the planning of the line.[68] The UERL's pre-opening predictions of passenger numbers for its other new lines proved to be similarly over-optimistic, as did the projected figures for the newly electrified DR – in each case, numbers achieved only around fifty per cent of their targets.[lower-alpha 13] 37,000 people used the line on the first day,[69] but in the months following the line's opening only about 20,000–30,000 passengers a day used the service. The number of carriages used by the BS&WR was cut back to three per train at peak times and only two during off-peak hours.[4] The Daily Mail reported in April 1906 that the rush-hour trains were carrying fewer than 100 people at a time.[69] To add to the line's misfortunes, it suffered its first fatality only two weeks after opening when conductor John Creagh was crushed between a train and a tunnel wall at Kennington Road station on 26 March.[70]

The lower than expected passenger numbers were partly due to competition between the tube and sub-surface railway companies, but the introduction of electric trams and motor buses, replacing slower, horse-drawn road transport, took a large number of passengers away from the trains.[71] The Daily Mirror noted at the end of April 1906 that the BS&WR offered poor value for money compared to the equivalent motor bus service, which cost only 1d. per journey, and that passengers disliked the distances that they had to walk between the trains and the lifts.[72] Such problems were not limited to the UERL; all of London's seven tube lines and the sub-surface DR and Metropolitan Railway were affected to some degree. The reduced revenue generated from the lower passenger numbers made it difficult for the UERL and the other railways to pay back the capital borrowed, or to pay dividends to shareholders.[71]

From 1907, in an effort to improve their finances, the UERL, the C&SLR, the CLR and the GN&CR began to introduce fare agreements. From 1908, they began to present themselves through common branding as the Underground.[71] The W&CR was the only tube railway that did not participate in the arrangement, as it was owned by the mainline L&SWR.[73]

The UERL's three tube railway companies were still legally separate entities, with their own management, shareholder and dividend structures. There was duplicated administration between the three companies and, to streamline the management and reduce expenditure, the UERL announced a bill in November 1909 that would merge the Bakerloo, the Hampstead and the Piccadilly Tubes into a single entity, the London Electric Railway (LER), although the lines retained their own individual branding.[74][lower-alpha 14] The bill received Royal Assent on 26 July 1910 as the London Electric Railway Amalgamation Act, 1910.[75]

Extensions

Paddington, 1906–13

Having planned a westward extension in 1900 to Willesden Junction, the company had been unable to decide on a route beyond Paddington and had postponed further construction while it considered options. In November 1905, the BS&WR announced a bill for 1906 that replaced the route from Edgware Road to Paddington approved in 1900 with a new alignment.[76] This had the tunnels crossing under the Paddington basin with the station under London Street. The tunnels were to continue south-east beyond the station as sidings, to end under the junction of Grand Junction Road and Devonport Street (now Sussex Gardens and Sussex Place).[77] In a pamphlet published in 1906 to publicise the Paddington extension, the company proclaimed:

[I]t will thus be seen that the advantages which this line will afford for getting quickly and cheaply from one point of London to another are without parallel. It will link up many of the most important Railway termini, give a connection with twelve other Railway systems, and connect the vast tramway system of the South of London, thus bringing the Theatres and other places of amusement, as well as the chief shopping centres, within easy reach of outer London and the suburbs.[78]

The changes were permitted by the Baker Street and Waterloo Railway Act, 1906 on 4 August 1906,[79] but the south-east alignment did not represent a suitable direction to continue the railway and no effort was made to construct the extension.[77]

In 1908, the Bakerloo Tube attempted to make the hoped-for extension into north-west London using the existing powers of the North West London Railway (NWLR), an unbuilt tube railway with permission to build a line from Cricklewood to Victoria station.[80] The NWLR announced a bill in November 1908 seeking to construct a 757-metre (2,484 ft) connection between its unbuilt route beneath the Edgware Road and the Bakerloo Tube's Edgware Road station.[81] The NWLR route to Victoria was to be abandoned south of the connection and the Bakerloo Tube's planned route to Paddington was to be built as a shuttle line from Edgware Road, which was to be provided with two additional platforms for shuttle use. The Bakerloo Tube was to construct the extension and operate the service over the combined route, which was to have stations at St John's Wood Road, Abercorn Place, Belsize Road (close to the LNWR station), Brondesbury (to interchange with the North London Railway's station and close to the MR's Kilburn station), Minster Road and Cricklewood.[80][82] The Bakerloo Tube announced its own bill to make the necessary changes to its existing plans.[83]

The GWR objected to the reduction of the Bakerloo Tube's Paddington connection to a shuttle and the MR objected to the connection of the two lines, which would be in competition with its line through Kilburn. Parliament rejected the proposed connection and the changes to the NWLR's route and the company's permissions eventually expired without any construction work being carried out. The Bakerloo Tube bill was withdrawn.[80]

In November 1910, the LER (of which the Bakerloo Tube was now part) revived plans for the Paddington extension when it published a bill for the 1911 Parliamentary session.[84] The new route ran 890 metres (2,920 ft) in a tight curve from Edgware Road station, initially heading south before turning to the north-west, which provided a more practical direction for a future extension. The bill was supported by the GWR with funding of £18,000.[85] The London Electric Railway Act, 1911 received royal assent on 2 June 1911.[86] Construction started in August 1911,[87] and was completed in a little over two years. The extension opened on 1 December 1913, with the single new station at Paddington.[61] Following their successful introduction at Earl's Court in 1911, the station was the first on the line to be designed to use escalators instead of lifts.[88]

Queen's Park and Watford, 1911–17

In 1907, the LNWR obtained parliamentary permission to improve its mainline services into London by the construction of a pair of new electrified tracks alongside its existing line between Watford Junction in Hertfordshire and Queen's Park, Kilburn and a new tube section beneath its lines from there to its terminus at Euston. At Euston, the tube tunnel was to end with an underground station on a 1,450-metre (4,760 ft) long loop beneath the mainline station.[89]

The LNWR began construction work on the surface section of the new tracks in 1909.[90] By 1911, it had modified the plans to omit the underground section and to split its proposed electrified services into three. The first section was to follow the existing surface route into Euston on newly electrified tracks, the second section was to connect with the North London Railway at Chalk Farm and continue on electrified tracks from there to Broad Street station in the City of London. The third section involved the extension of the Bakerloo Tube from Paddington to Queen's Park.[89]

With the extension to Paddington still under construction, the LER published a bill in November 1911 for the continuation to Queen's Park.[91] The extension was to continue north from Paddington, running past Little Venice to Maida Vale before curving north-west to Kilburn and then west to parallel the LNWR main line, before coming to the surface a short distance to the east of Queen's Park station. Three intermediate stations were to be provided: on Warwick Avenue at the junction with Warrington Avenue, Clifton Villas and Clifton Gardens; at the junction of Elgin and Randolph Avenues (named Maida Vale); and on Cambridge Avenue (named Kilburn Park). The LNWR gave a £1 million loan to the LER at 4% interest in perpetuity to help finance the extension.[89] The bill received royal assent on 7 August 1912 as the London Electric Railway Act, 1912.[92]

Progress on the section from Paddington to Queen's Park was slowed by the start of World War I, so the line was not finished until early 1915.[88] As at Paddington, the three below-ground stations were built to use escalators. Maida Vale and Kilburn Park were provided with buildings in the style of the earlier Leslie Green stations but without the upper storey, which was no longer required for housing lift gear. Warwick Avenue was accessed from a subway under the street.[93] The LNWR rebuilt Queen's Park station with additional platforms for the Bakerloo Tube's and its own electric services and constructed two train sheds for rolling stock, one each side of the station.[94]

Although the tracks were completed to Queen's Park, delays to the completion of the stations caused the extension to open in stages:[61]

- Warwick Avenue, on 31 January 1915

- Maida Vale, on 6 June 1915

- Kilburn Park, on 31 January 1915

- Queen's Park, on 11 February 1915

North of Queen's Park, the LNWR had opened its new lines between Willesden Junction and Watford during 1912 and 1913, together with new stations at Harlesden, Stonebridge Park, North Wembley, Kenton and Headstone Lane.[95] The new tracks between Queen's Park and Willesden Junction opened on 10 May 1915, when Bakerloo Tube services were extended there. On 16 April 1917, the tube service was extended to Watford Junction. North of Queen's Park, the Bakerloo Tube served the following stations:[61]

- Kensal Green

- Willesden Junction

- Harlesden

- Stonebridge Park

- Wembley for Sudbury (now Wembley Central)

- North Wembley

- Kenton

- Harrow & Wealdstone

- Headstone Lane

- Pinner & Hatch End (later Hatch End for Pinner, now Hatch End)

- Carpenders Park, opened 5 May 1919

- Bushey & Oxhey (now Bushey)

- Watford High Street

- Watford Junction

For the extension to Queen's Park, the LER supplemented the existing rolling stock with 14 new carriages ordered from Brush Traction and Leeds Forge Company plus spare Gate stock carriages from the GNP&BR. These carriages, the 1914 stock, were the first to have doors in the sides of the carriages as well as the ends.[94] For the longer extension to Watford, the LER and the LNWR ordered 72 new carriages from the Metropolitan Railway Carriage and Wagon Company. Manufacture of this rolling stock was delayed by the war, and, while it was waiting for delivery, the Bakerloo Tube used spare 1915 stock carriages ordered for an unfinished extension of the CLR to Ealing Broadway and more spare Gate stock carriages from the GNP&BR.[95] Delivery of the carriages for the Watford service, known as the Watford Joint stock because ownership was shared with the LNWR, began in 1920; they were painted in the LNWR's livery to distinguish them from trains operating only on the Bakerloo Tube's tracks.[96]

Camberwell and south-east London

The southern termination of the line at Elephant & Castle presented the opportunity for the line to be extended further, to serve Camberwell and other destinations in south-east London. In 1913, the Lord Mayor of London announced a proposal for the Bakerloo Tube to be extended to the Crystal Palace via Camberwell Green, Dulwich and Sydenham Hill, but nothing was done to implement the plan.[97] In 1921, the LER costed an extension to Camberwell, Dulwich and Sydenham and in 1922 plans for an extension to Orpington via Loughborough Junction and Catford were considered. In 1928, a route to Rushey Green via Dulwich was suggested. Again, no action was taken, although the London and Home Counties Traffic Advisory Committee approved an extension to Camberwell in 1926.[98]

In 1931, an extension to Camberwell was approved as part of the London Electric Metropolitan District and Central London Railway Companies (Works) Act, 1931.[99][100] The route was to follow Walworth Road and Camberwell Road south from Elephant and Castle, with stations at Albany Road and under Denmark Hill road at Camberwell. Elephant & Castle station was to be reconstructed with a third platform, a new ticket hall and escalators. However, financial constraints prevented any work from being started.[98]

Improvements, 1914–28

Overcrowding was a major problem at many stations where interchanges were made with other Underground lines and efforts were made in a number of places to improve passenger movements. In 1914, work was carried out to provide larger ticket halls and install escalators at Oxford Circus, Embankment and Baker Street. In 1923, further work at Oxford Circus provided a combined Bakerloo and CLR ticket hall and added more escalators serving the CLR platforms. In 1926, Trafalgar Square and Waterloo received escalators, the latter in conjunction with expansion of the station as part of the CCE&HR's extension to Kennington. Between 1925 and 1928, Piccadilly Circus station saw the greatest reconstruction. A large circular ticket hall was excavated below the road junction with multiple subway connections from points around the Circus and two flights of escalators down to the Bakerloo and Piccadilly platforms were installed.[101]

Move to public ownership, 1923–33

Despite closer co-operation and improvements made to the Bakerloo stations and to other parts of the network,[lower-alpha 15] the Underground railways continued to struggle financially. The UERL's ownership of the highly profitable London General Omnibus Company (LGOC) since 1912 had enabled the UERL group, through the pooling of revenue, to use profits from the bus company to subsidise the less profitable railways.[lower-alpha 16] However, competition from numerous small bus companies during the early 1920s eroded the profitability of the LGOC and had a negative impact on the profitability of the whole UERL group.[103]

To protect the UERL group's income, its chairman Lord Ashfield lobbied the government for regulation of transport services in the London area. Starting in 1923, a series of legislative initiatives were made in this direction, with Ashfield and Labour London County Councillor (later MP and Minister of Transport) Herbert Morrison at the forefront of debates as to the level of regulation and public control under which transport services should be brought. Ashfield aimed for regulation that would give the UERL group protection from competition and allow it to take substantive control of the LCC's tram system; Morrison preferred full public ownership.[104] After seven years of false starts, a bill was announced at the end of 1930 for the formation of the London Passenger Transport Board (LPTB), a public corporation that would take control of the UERL, the Metropolitan Railway and all bus and tram operators within an area designated as the London Passenger Transport Area.[105] The Board was a compromise – public ownership but not full nationalisation – and came into existence on 1 July 1933. On this date, the LER and the other Underground companies were liquidated.[106]

Legacy

The plan for the extension to Camberwell was kept alive throughout the 1930s and, in 1940, the permission was used to construct sidings beyond Elephant & Castle. After the Second World War, the plans were revised again, with stations located under Walworth Road and Camberwell Green, and the extension appeared on tube maps in 1949.[107] Rising construction costs caused by difficult ground conditions and restricted funds in the post-war austerity period led the scheme to be cancelled again in 1950.[108] Various proposals have been evaluated since, including an extension to Peckham considered in the early 1970s, but the costs have always out-weighed the benefits.[109]

One of the LPTB's first acts in charge of the Bakerloo line was the opening of a new station at South Kenton on 3 July 1933.[61] As part of the LPTB's New Works Programme announced in 1935, new tube tunnels were constructed from Baker Street to the former MR station at Finchley Road and the Bakerloo line took over the stopping service to Wembley Park and the MR's Stanmore branch.[110] The service opened in November 1939 and remained part of the Bakerloo line until 1979 when it transferred to the Jubilee line.[61]

The Bakerloo line's Watford service frequency was gradually reduced and from 1965 ran only during rush hours. In 1982, the service beyond Stonebridge Park was ended as part of the fall-out of the cancellation of the Greater London Council's Fares Fair subsidies policy.[111] A peak hours service was restored to Harrow & Wealdstone in 1984 and a full service was restored in 1989.[112]

Notes and references

Notes

- A "tube" railway is an underground railway constructed in a cylindrical tunnel by the use of a tunnelling shield, usually deep below ground level, as opposed to "cut-and-cover". See Tunnel#Construction.

- In its first year of operation the C&SLR carried 5.1 million passengers.[6]

- The Central London Railway received Royal Assent on 5 August 1891, the Great Northern & City Railway Act received Royal Assent on 28 June 1892, the Waterloo and City Railway Act received Royal Assent on 8 March 1893 and the Charing Cross, Euston & Hampstead Railway Act received Royal Assent on 24 August 1893.[11]

- Time limits were included in such legislation to encourage the railway company to complete the construction of its line as quickly as possible. They also prevented unused permissions acting as an indefinite block to other proposals.

- Yerkes' consortium first purchased the CCE&HR in September 1900. In March 1901, it purchased a majority of the shares of the District Railway and, in September 1901, took over the Brompton and Piccadilly Circus Railway and the Great Northern and Strand Railway.[22]

- Yerkes was Chairman of the UERL with the other main investors being investment banks Speyer Brothers (London), Speyer & Co. (New York) and Old Colony Trust Company (Boston).[22]

- Like many of Yerkes' schemes in the United States, the structure of the UERL's finances was highly complex and involved the use of novel financial instruments linked to future earnings. Over-optimistic expectations of passenger usage meant that many investors failed to receive the returns expected.[23]

- The Metropolitan Railway opened on 10 January 1863, running in a mainly cut and cover tunnel dug under the road between Paddington and Farringdon. By 1899, it was extended far out into Middlesex, Hertfordshire and Buckinghamshire.

- Trafalgar Square and Regent's Park stations were built with subway access from the street instead of surface buildings. Waterloo station was provided with a simple archway entrance in the UERL style without the normal station building.

- The lifts, supplied by American manufacturer Otis,[52] were installed in pairs within 23 ft diameter shafts.[53] The number of lifts depended on the expected passenger demand at the stations: for example, Hampstead has four lifts but Chalk Farm and Mornington Crescent have two each.[54]

- During the planning phase, the station at Marylebone was named to correspond with the main line station it served. It was opened as Great Central at the request of Sam Fay, the Great Central Railway's chairman.[62]

- Trains entered service by running north into Kennington Road station.

- The UERL had predicted 60 million passengers for the GNP&BR and 50 million for the CCE&HR in their first year of operation, but achieved 26 and 25 million respectively. For the DR it had predicted an increase to 100 million passengers after electrification, but achieved 55 million.[68]

- The merger was carried out by transferring the assets of the BS&WR and the CCE&HR to the GNP&BR and renaming the GNP&BR the London Electric Railway.

- The CLR extension to Ealing Broadway opened in 1920, the CCE&HR extension to Edgware opened in 1923/24 and the C&SLR extension to Morden opened in 1926.[61]

- By having a virtual monopoly of bus services, the LGOC was able to make large profits and pay dividends far higher than the underground railways ever had. In 1911, the year before its take over by the UERL, the dividend had been 18 per cent.[102]

References

- Length of line calculated from distances given at "Clive's Underground Line Guides, Bakerloo line, Layout". Clive D. W. Feathers. Archived from the original on 24 November 2009. Retrieved 7 November 2009.

- Lee 1966, p. 7.

- Lee 1966, p. 8.

- Lee, Charles E. (March 1956). "Jubilee of the Bakerloo Railway – 1". The Railway Magazine: 149–156.

- Short History 1906, p. 1.

- Wolmar 2005, p. 321.

- "No. 26225". The London Gazette. 20 November 1891. pp. 6145–6147.

- Badsey-Ellis 2005, p. 56.

- "No. 26387". The London Gazette. 31 March 1893. p. 1987.

- Badsey-Ellis 2005, p. 78.

- Badsey-Ellis 2005, pp. 47, 57, 59, 60.

- Badsey-Ellis 2005, p. 61.

- Badsey-Ellis 2005, pp. 57, 112.

- "No. 26682". The London Gazette. 21 November 1895. pp. 6410–6411.

- "No. 26767". The London Gazette. 11 August 1896. pp. 4572–4573.

- Badsey-Ellis 2005, pp. 113–114.

- "The Baker Street and Waterloo Railway". The Times (35808): 7–8. 20 April 1899. Retrieved 7 November 2009.

- UK Retail Price Index inflation figures are based on data from Clark, Gregory (2017). "The Annual RPI and Average Earnings for Britain, 1209 to Present (New Series)". MeasuringWorth. Retrieved 2 February 2020.

- Expenditure is recorded as £654,705 10s 7d in a prospectus issued by the BS&WR in November 1900 – "The Baker Street and Waterloo Railway – Prospectus". The Times. 13 November 1900. Retrieved 7 November 2009.

- Horne 2001, p. 9.

- Day & Reed 2008, p. 69.

- Badsey-Ellis 2005, p. 118.

- Wolmar 2005, pp. 170–172.

- "No. 26914". The London Gazette. 26 November 1897. pp. 7057–7059.

- Badsey-Ellis 2005, pp. 77–78.

- Badsey-Ellis 2005, p. 84.

- Wolmar 2005, p. 168.

- "No. 27025". The London Gazette. 22 November 1898. pp. 7070–7073.

- Short History 1906, p. 3.

- "No. 27105". The London Gazette. 4 August 1899. pp. 4833–4834.

- "No. 27137". The London Gazette. 21 November 1899. pp. 7181–7183.

- Badsey-Ellis 2005, pp. 84–85.

- "No. 27218". The London Gazette. 7 August 1900. pp. 4857–4858.

- "No. 27380". The London Gazette. 26 November 1901. p. 8129.

- "No. 27497". The London Gazette. 21 November 1902. p. 7533.

- "No. 27498". The London Gazette. 25 November 1902. pp. 7992–7994.

- Badsey-Ellis 2005, p. 203.

- "No. 27588". The London Gazette. 14 August 1903. pp. 5143–5144.

- "No. 27618". The London Gazette. 20 November 1903. pp. 7203–7204.

- "No. 27699". The London Gazette. 26 July 1904. pp. 4827–4828.

- Horne 2001, p. 7.

- Pennick 1983, p. 19.

- Pennick 1983, p. 21.

- Pennick 1983, p. 22.

- "The Underground Electric Railways Company Of London (Limited)". The Times (36738): 12. 10 April 1902. Retrieved 7 November 2009.

- "Railway And Other Companies – Baker Street and Waterloo Railway". The Times (37319): 14. 17 February 1904. Retrieved 7 November 2009.

- Wolmar 2005, p. 173.

- Horne 2001, p. 20.

- Horne 2001, p. 19.

- Wolmar 2005, p. 175.

- Lee 1966, p. 15.

- Wolmar 2005, p. 188.

- Connor 2006, plans of stations.

- "Clive's Underground Line Guides, Lifts and Escalators". Clive D. W. Feathers. Archived from the original on 14 November 2009. Retrieved 7 November 2009.

- Horne 2001, p. 18.

- Short History 1906, p. 14.

- Short History 1906, p. 13.

- Horne 2001, p. 17.

- Wolmar 2005, pp. 174–175.

- "1908 tube map". A History of the London Tube Maps. Archived from the original on 23 February 2009. Retrieved 7 November 2009.

- Rose 1999.

- Day & Reed 2008, p. 71.

- Horne 2001, pp. 12–13.

- Horne 2001, p. 13.

- Day & Reed 2008, p. 70.

- Short History 1906, p. 15.

- Lee, Charles E. (March 1956). "Jubilee of the Bakerloo Railway – 1". The Railway Magazine: 255–259.

- Wolmar 2005, p. 191.

- Lee 1966, p. 13.

- "First Bakerloo Tragedy". Daily Mirror. 31 March 1906. p. 5.

- Badsey-Ellis 2005, pp. 282–283.

- "Expensive 'Bakerloo' Fares". Daily Mirror. 30 April 1906. p. 4.

- Horne 2001, p. 23.

- "No. 28311". The London Gazette. 23 November 1909. pp. 8816–8818.

- "No. 28402". The London Gazette. 29 July 1910. pp. 5497–5498.

- "No. 27856". The London Gazette. 21 November 1905. pp. 8124–8126.

- Badsey-Ellis 2005, pp. 267–268.

- Short History 1906, p. 7.

- "No. 27938". The London Gazette. 7 August 1906. pp. 5453–5454.

- Badsey-Ellis 2005, pp. 264–267.

- "No. 28199". The London Gazette. 24 November 1908. pp. 8824–8827.

- Badsey-Ellis 2005, pp. 80–81.

- "No. 28199". The London Gazette. 24 November 1908. pp. 8951–8952.

- "No. 28439". The London Gazette. 22 November 1910. pp. 8408–8411.

- Horne 2001, pp. 28–29.

- "No. 28500". The London Gazette. 2 June 1911. p. 4175.

- "Paddington Linked Up With The "Bakerloo" Line". The Times (40383): 70. 1 December 1913. Retrieved 7 November 2009.

- Horne 2001, p. 29.

- Badsey-Ellis 2005, pp. 268–270.

- Horne 2001, p. 27.

- "No. 28552". The London Gazette. 21 November 1911. pp. 8615–8620.

- "No. 28634". The London Gazette. 9 August 1912. pp. 5915–5916.

- Horne 2001, p. 30.

- Horne 2001, p. 31.

- Horne 2001, p. 33.

- Horne 2001, p. 37.

- Badsey-Ellis 2005, p. 268.

- Horne 2001, pp. 40–41.

- "No. 33699". The London Gazette. 17 March 1931. pp. 1809–1811.

- "No. 33761". The London Gazette. 9 October 1931. p. 6462.

- Horne 2001, pp. 38–39.

- Wolmar 2005, p. 204.

- Wolmar 2005, p. 259.

- Wolmar 2005, pp. 259–262.

- "No. 33668". The London Gazette. 9 December 1930. pp. 7905–7907.

- Wolmar 2005, p. 266.

- "History of the London Tube Map, 1949 tube map". London Transport. June 1949. Archived from the original on 25 January 2008. Retrieved 7 November 2009.

- Horne 2001, p. 57.

- Horne 2001, pp. 63–66.

- Horne 2001, pp. 46–48.

- Horne 2001, pp. 72–73.

- Horne 2001, p. 78.

Bibliography

- Short History and Description of the Baker Street and Waterloo Railway. Baker Street and Waterloo Railway Company. 1906.

- Badsey-Ellis, Antony (2005). London's Lost Tube Schemes. Harrow: Capital Transport. ISBN 978-1-85414-293-1.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Connor, J.E. (2006) [2001]. London's Disused Underground Stations. Harrow: Capital Transport. ISBN 978-1-85414-250-4.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Day, John R; Reed, John (2008) [1963]. The Story of London's Underground. Harrow: Capital Transport. ISBN 978-1-85414-316-7.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Horne, Mike (2001). The Bakerloo Line: An Illustrated History. Harrow: Capital Transport. ISBN 978-1-85414-248-1.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Lee, Charles E. (1966). Sixty years of the Bakerloo. London: London Transport.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Pennick, Nigel (1983). Early Tube Railways of London. Cambridge: Electric Traction Publications.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Rose, Douglas (1999) [1980]. The London Underground, A Diagrammatic History. Harrow: Douglas Rose/Capital Transport. ISBN 978-1-85414-219-1.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Wolmar, Christian (2005) [2004]. The Subterranean Railway: How the London Underground Was Built and How It Changed the City Forever. London: Atlantic Books. ISBN 978-1-84354-023-6.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Baker Street and Waterloo Railway. |