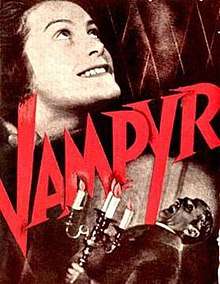

Vampyr

Vampyr (German: Vampyr – Der Traum des Allan Gray, lit. 'Vampyr: The Dream of Allan Gray') is a 1932 horror film directed by Danish director Carl Theodor Dreyer. The film was written by Dreyer and Christen Jul based on elements from J. Sheridan Le Fanu's 1872 collection of supernatural stories In a Glass Darkly. Vampyr was funded by Nicolas de Gunzburg who starred in the film under the name of Julian West among a mostly non-professional cast. Gunzburg plays the role of Allan Gray, a student of the occult who enters the village of Courtempierre, which is under the curse of a vampire.

| Vampyr | |

|---|---|

| |

| Directed by | Carl Theodor Dreyer |

| Produced by | Carl Theodor Dreyer Julian West |

| Screenplay by | Christen Jul Carl Theodor Dreyer |

| Based on | In a Glass Darkly 1872 story by Sheridan Le Fanu |

| Starring | Julian West[3] Maurice Schutz Rena Mandel Jan Hieronimko Sybille Schmitz Henriette Gerard |

| Music by | Wolfgang Zeller |

| Cinematography | Rudolph Maté |

| Edited by | Tonka Taldy Carl Theodor Dreyer[4] |

Production company |

|

| Distributed by | Germany: Vereinigte Star-Film GmbH[6] |

Release date | 6 May 1932 (Germany) September 1932 (Paris) |

Running time | 73 minutes |

| Country |

|

| Language | German intertitles |

Vampyr was challenging for Dreyer to make as it was his first sound film and was required to be recorded in three languages. To overcome this, very little dialogue was used in the film and much of the story is told with silent film-styled title cards. The film was shot entirely on location and to enhance the atmospheric content, Dreyer opted for a washed out, soft focus photographic technique. The soundtrack was created in Berlin where the character's voices, sound effects, and score were recorded.

Vampyr had a delayed release in Germany and opened to a generally negative reception from audiences and critics. Dreyer edited the film after its German premiere and it opened to more mixed opinions at its French debut. The film was long considered a low point in Dreyer's career, but modern critical reception to the film has become much more favorable with critics praising the film's disorienting visual effects and atmosphere.

Plot

On a late evening, Allan Gray arrives at an inn close to the village of Courtempierre and he rents a room to sleep. Gray is awakened suddenly by an old man, who enters the room and leaves a square packet on Gray's table; "To be opened upon my death" is written on the wrapping paper. Gray takes the package and walks outside. Shadows guide him to an old castle, where he sees the shadows dancing and wandering on their own. Gray also sees an elderly woman (later identified as Marguerite Chopin) and encounters another old man (later identified as the village doctor). Gray leaves the castle and walks to a manor. Looking through one of the windows, Gray sees the Lord of the manor, the same man who gave him the package earlier. The man is suddenly murdered by gunshot. Gray is let into the house by servants, who rush to the aid of the fallen man but it is too late to save him. The servants ask Gray to stay the night. Gisèle, the younger daughter of the now deceased Lord of the manor, takes Gray to the library and tells him that her sister, Léone, is gravely ill. Just then they see Léone walking outside. They follow her, and find her unconscious on the ground with fresh bite wounds. They have her carried inside. Gray remembers the parcel and opens it. Inside is a book about horrific demons called Vampyrs.

By reading the book, Gray learns that Léone is a victim of a Vampyr. Vampyrs can force humans into submission. The village doctor visits Léone at the manor, and Gray recognizes him as the old man he saw in the castle. The doctor tells Gray that a blood transfusion is needed and Gray offers his blood to save Léone. Exhausted from blood loss, Gray sleeps. He wakes sensing danger and rushes to Léone, where he surprises the doctor as he is attempting to poison the girl. The doctor flees the manor, and Gray finds that Gisèle is gone. Gray follows the doctor back to the castle, where Gray has a vision of himself being buried alive. After the vision subsides, he rescues Gisèle but the doctor escapes. The old servant of the manor finds Gray's Vampyr book and discovers that a Vampyr can be defeated by driving an iron bar through its heart. The servant meets Gray at Marguerite Chopin's grave behind the village Chapel. They open the grave and find the old woman perfectly preserved. They hammer a large metal bar through her heart, killing her. The village doctor is hiding in an old mill, but finds himself locked in a chamber where flour sacks are filled. The old servant arrives and activates the mill's machinery, filling the chamber with flour and suffocating the doctor. The curse of the Vampyr is lifted and Léone suddenly recovers. Gisèle and Gray cross a foggy river by boat and find themselves in a bright clearing.[8]

Cast

- Nicolas de Gunzburg (credited as Julian West[3]) as Allan Gray, a young wanderer whose studies of occult matters have made him a dreamer. Gray's view of the world in the film is described as a blur of the real and unreal.

- Rena Mandel as Giséle, Léone's younger sister and the daughter of the Lord of the Manor. Giséle is kidnapped by the Village Doctor late in the film.

- Sybille Schmitz as Léone, Giséle's older sister, who is in thrall to the vampire and finds her strength dwindling day by day.

- Jan Hieronimko as the Village Doctor, a pawn of the vampire, Marguerite Chopin, who seems to sleep in a coffin, hinting that he too may be a vampire. The village doctor kidnaps Giséle late in the film.

- Henriette Gérard as Marguerite Chopin, the vampire, an elderly woman whose hold extends beyond her immediate victims. Many villagers, including the village doctor, are her minions.

- Maurice Schutz as the Lord of the Manor, Giséle and Léone's father who offers Gray a book about vampirism to help Gray save his daughters. After his murder, he returns briefly as a spirit and takes revenge on the village doctor and a soldier who had helped Marguerite Chopin.

- Albert Bras as an Old Servant, a servant at the manor house. After the death of his master, he finds Gray's book on vampirism and, aided by Gray, ends the vampire's reign of terror.

- N. Babanini as Seine Frau (His Wife)

- Jane Mora as a Nurse

- Georges Boidin as the Limping Soldier

Production

Development

Director Carl Theodor Dreyer began planning Vampyr in late 1929, a year after the release of his previous film The Passion of Joan of Arc.[9][10] The production company behind Dreyer's previous film had plans for Dreyer to make another film, but the project was dropped which led to Dreyer deciding to go outside the studio system to make his next film.[9] Being Dreyer's first sound film, it was made under difficult circumstances as the arrival of sound put the European film industry in turmoil. In France, film studios lagged behind technologically with the first French sound films being shot on sound stages in England.[9] Dreyer went to England to study sound film, where he got together with Danish writer Christen Jul who was living in London at the time.[9] Dreyer decided to create a story based on the supernatural and read over thirty mystery stories and found a number of re-occurring elements including doors opening mysteriously and door handles moving with no one knowing why. Dreyer decided that "We can jolly well make this stuff too".[9] In London and New York, the stage version of Dracula had been a large hit in 1927.[9] Dreyer and Jul created a story based on vampires which Dreyer considered to be "fashionable things at the time".[9] Vampyr is based on elements from J. Sheridan Le Fanu's In a Glass Darkly, a collection of five stories first published in 1872.[1] Dreyer draws from two of the stories for Vampyr, one being Carmilla, a lesbian vampire story and the other being The Room in the Dragon Volant about a live burial.[11] Dreyer found it difficult to decide on a title for the film. It may have initially been titled Destiny and then Shadows of Hell.[1] When the film was presented in the film journal Close Up it was titled The Strange Adventure of David Gray.[1]

Pre-production

Dreyer returned to France to begin casting and location scouting. At the time in France, there was a small movement of artistic independently financed films, including Luis Buñuel's L'Âge d'Or and Jean Cocteau's The Blood of a Poet which were both released in 1930.[11] Through Valentine Hugo, Dreyer met Nicolas de Gunzburg, an aristocrat who agreed to finance Dreyer's next film in return for playing the lead role in it.[9] Gunzberg had arguments with his family about becoming an actor, so he created the pseudonym Julian West, a name that would be the same in all three languages that the film was going to be shot in.[12]

Most of the cast in Vampyr were not professional actors. Jan Hieronimko, who plays the village doctor, was found on a late night metro train in Paris. When approached to act in the film, Hieronimko stared blankly and did not reply. Hieronimko later contacted Dreyer's crew and agreed to join the film.[11] Many of the other non-professional actors in the film were found in similar fashion in shops and cafés.[12] The only professional actors in the film were Maurice Schutz, who plays the Lord of the Manor, and Sybille Schmitz, who plays his daughter Léone.[12] Many crew members of Vampyr had worked with Dreyer on his previous film The Passion of Joan of Arc. Returning crew members included cinematographer Rudolph Maté and art director Hermann Warm.[4]

The entire film was shot on location with many scenes shot in Courtempierre, France.[11][13] Dreyer and his cinematographer Rudolph Maté contributed to the location scouting for Vampyr. Dreyer left most of his scouting to an assistant, who Dreyer instructed to find "a factory in ruins, a chopped up phantom, worthy of the imagination of Edgar Allan Poe. Somewhere in Paris. We can't travel far."[13] In the original script, the village doctor was intended to flee the village and get trapped in a swamp. On looking for a suitable mire, the crew found a mill where they saw white shadows around the windows and doors.[13] After seeing this place, they changed the film's ending to take place at this mill where the doctor dies by suffocating under the milled flour.[13]

Filming

Vampyr was filmed between 1930 and 1931.[11] Everything being shot on location, as Dreyer believed it would be beneficial by lending the dream-like ghost world of the film as well as allowing them to save money by not having to rent studio space.[13] Dreyer originally wanted Vampyr to be a silent film, as it uses many elements of the silent era such as title cards to explain the story.[11][14] Dialogue in the film was kept to a minimum.[11] For the scenes with dialogue, the actors mouthed their lines in French, German and English so their lip movements would correspond to the voices that were going to be recorded in post-production.[14] There is no record of the English version being completed.[14] The scenes in the chateau were shot in April and May 1930. The chateau also acted as housing for the cast and crew during the filming. Life in the chateau was unpleasant for them as it was cold and infested with rats.[1][13] The church yard scenes were shot in August 1930. The church was not an actual church, but a barn with a number of tombstones placed around it. This set was designed by the art director Hermann Warm.[13]

Critic and writer Kim Newman described Vampyr's style as closer to the experimental features such as Un Chien Andalou (1929) than a "quickie horror film" made after the release of Dracula (1931).[15] Dreyer originally was going to film Vampyr in what he described as a "heavy style" but changed direction after cinematographer Maté showed him one shot that came out fuzzy and blurred.[1][16] This washed out look was an effect Dreyer desired, and he had Maté shoot the film through a piece of gauze held three feet (.9 m) away from the camera to re-create this look.[16] For other visuals in the film, Dreyer found inspiration from the fine arts.[1] Actress Rena Mandel, who plays Gisèle, said that Dreyer showed her reproductions of paintings of Francisco Goya during filming.[1] In Denmark, a journalist and friend of Dreyer, Henry Hellsen wrote in detail about the film and the artworks it appeared to draw on.[1] When being asked about the intention of the film at the Berlin premiere, Dreyer replied that he "had not any particular intention. I just wanted to make a film different from all other films. I wanted, if you will, to break new ground for the cinema. That is all. And do you think this intention has succeeded? Yes, I have broken new ground".[9] The filming of Vampyr was completed the middle of 1931.[11]

Post-production

Dreyer shot and edited the film in France and then brought it to Berlin where it was post-synchronized in both German and French.[19] Dreyer did the audio work at Universum Film AG, as they had the best sound equipment available to him at the time.[12] Most of the actors did not dub their own voices. The only voices of the actors that are their own in the film are of Schmitz and Gunzburg.[12] The sounds of dogs, parrots, and other animals in the film were fake and were created by professional imitators.[12] Wolfgang Zeller composed the film's score and worked with Dreyer to develop the music.[12]

There are differences between the German and French releases of the film. The character Allan Grey is named David Gray for the German release, which Dreyer attributed to a mistake.[14] The German censors ordered cuts to the film that still exist today in some prints.[14] The scenes which had to be toned down include the doctor's death under the milled flour and the vampire's death from the stake.[14] There are other scenes that were included in the script and shot that do not exist in any current prints of Vampyr. These scenes reveal the vampire in the factory recoiling against a shadow of a Christian cross as well as a ferryman guiding Gray and Gisèle by getting young children to build a fire and sing a hymn to guide them back to the shore.[14]

Dreyer had prepared a Danish version of the film which was based on the German version with Danish subtitles and title cards.[20] The distributor could not afford to have the title cards completed in the manner they appear in the German version, which were instead finished with a more simple style.[20] The distributor also wanted to make the pages in the book shown in the film as plain title cards which Dreyer did not allow, saying that "the old book is not an text in the ordinary sense, but an actor. Just as much as the others."[20]

Release

The premiere of Vampyr in Germany was delayed by UFA, as the studio wanted the American films Dracula and Frankenstein to be released first.[11] The Berlin premiere was on 6 May 1932.[19][20] At this premiere, the audience booed the film which led to Dreyer cutting several scenes out of the film after the first showing.[14] The film was distributed in France by Société Générale de Cinema who also distributed Dreyer's previous film The Passion of Joan of Arc.[11] The Paris premiere was in September 1932 where Vampyr was the opening attraction of a new cinema on the Boulevard Raspail.[20][21] At a showing of the film in Vienna, audiences demanded their money back. When this was denied, a riot broke out that led to police having to restore order with night sticks.[14] When the film premiered in Copenhagen, Denmark in March 1933, Dreyer did not attend. In the USA, the film premiered with English subtitles under the title Not Against The Flesh; an English-dubbed version, edited severely as to both the film continuity and the music track, appeared a few years later on the roadshow circuit as Castle of Doom. Dreyer soon had a nervous breakdown and went to a mental hospital in France.[20] The film was a financial failure.[22]

Critical reception

Press in Europe ranged from mixed to negative. The press in Germany did not like the film.[12] At the Berlin premiere, a film critic from The New York Times wrote: "Whatever you think of the director Charles [sic] Theodor Dreyer, there is no denying that he is 'different'. He does things that make people talk about him. You may find his films ridiculous—but you won't forget them...Although in many ways [Vampyr] was one of the worst films I have ever attended, there were some scenes in it that gripped with brutal directness".[23] Press reaction to the film in Paris was mixed.[12] Reporter Herbert Matthews of The New York Times wrote that Vampyr was "a hallucinating film", that "either held the spectators spellbound as in a long nightmare or else moved them to hysterical laughter".[21] For many years after Vampyr's initial release, the film was viewed by critics as one of Dreyer's weaker works.[24]

More modern reception for Vampyr has been more positive. The review aggregator website Rotten Tomatoes reports an approval rating of 100% based upon a sample of 30 reviews, with an average rating of 8.83/10. The site's critical consensus reads, "Full of disorienting visual effects, Carl Theodor Dreyer's Vampyr is as theoretically unsettling as it is conceptually disturbing."[25] Todd Kristel of the online film database AllMovie gave the film four and a half stars out of five, stating that "Vampyr isn't the easiest classic film to enjoy, even if you are a fan of 1930s horror movies...If you're patient with the slow pacing and ambiguous story line of Vampyr, you'll find that this film offers many striking images" and that although the film is "not exciting in terms of pacing, it's a good choice if you want to see a film that establishes a compelling mood".[17] Jonathan Rosenbaum of the Chicago Reader wrote, "The greatness of Carl Dreyer's [Vampyr] derives partly from its handling of the vampire theme in terms of sexuality and eroticism and partly from its highly distinctive, dreamy look, but it also has something to do with Dreyer's radical recasting of narrative form".[18] J. Hoberman of the Village Voice wrote that "Vampyr is Dreyer's most radical film—maybe one of my dozen favorite movies by any director".[23] Anton Bitel of Channel 4 awarded the film four and a half stars out of five, comparing it to the silent vampire film Nosferatu, stating that it is "lesser known (but in many ways superior)" and that the film is "a triumph of the irrational, Dreyer's eerie memento mori never allows either protagonist or viewer fully to wake up from its surreal nightmare".[26]

In the early 2010s, the London edition of Time Out conducted a poll with several authors, directors, actors and critics who have worked within the horror genre to vote for their top horror films.[27] Vampyr placed at number 50 on their top 100 list.[28]

Home media

Vampyr has been released with imperfect image and sound as the original German and French sound and film negatives are lost.[19] Prints of the French and German versions of the film exist but most of them are either incomplete or damaged.[19] Vampyr was released in the United States under the titles of The Vampire, and Castle of Doom and in the United Kingdom under the title of The Strange Adventures of David Gray.[29] Many of these prints are severely cut, such as the re-dubbed 60-minute English-language Castle of Doom print.[24]

Vampyr was originally released on DVD on 13 May 1998 by Image Entertainment which ran at an abridged 72-minute running time.[30][31] Image's release of Vampyr is a straight port of the Laserdisc that film restorer David Shepard produced in 1991. The subtitles are large and ingrained due to the source print having Danish subtitles which have been blacked out and covered.[32] This DVD also included the short film The Mascot as a bonus feature.[31] The Criterion Collection released a two-disc edition of Vampyr on 22 July 2008.[33] This edition of the DVD includes the original German version of the film, along with a book featuring Dreyer and Christen Jul's original screenplay and Sheridan Le Fanu's 1872 story "Carmilla".[33] A Region 2 DVD of the film was released by Eureka Films on 25 August 2008.[34] The Eureka release contains the same bonus material as the Criterion Collection discs, but also includes a commentary from director Guillermo del Toro.[35]

In October 2017, Criterion released the film on Blu-ray. This version was made from a new HD digital transfer of the 1998 restoration.[36]

See also

- List of French films of 1932

- List of German films 1919–1933

- List of horror films of the 1930s

- Vampire film

References

- Tybjerg, Casper (2008). Visual Essay: Spiritual influences (DVD). New York City, United States: The Criterion Collection.

- "Vampyr booklet". Masters of Cinema. Retrieved 14 July 2009.

- "Vampyr: No 9 best horror film of all time". Guardian. Guardian Online. Retrieved 2 June 2020.

- Bazin, . p. 103

- "Credits". British Film Institute. Archived from the original on 16 January 2009. Retrieved 11 March 2015.

- Rudkin, 2005. p. 79

- "Vampyr Der Traum des Allan Grey". BFI Film & Television Database. British Film Institute. Archived from the original on 16 January 2009. Retrieved 23 April 2014.

- Dreyer, Carl Theodor. Four Screenplays. Bloomington & London: Indiana University Press. 1970. ISBN 0-253-12740-8. pp. 79–129.

- Tybjerg, Casper (2008). Visual Essay: The rise of the vampire (DVD). New York City, United States: The Criterion Collection.

- "The Passion of Joan of Arc > Overview". Allmovie. Macrovision. Retrieved 14 July 2009.

- Rayns, Tony (2008). DVD Commentary (DVD). New York City, United States: The Criterion Collection.

- Vampyr (Booklet interview with Nicolas de Gunzberg). Carl Theodor Dreyer. New York, United States: The Criterion Collection. 2008 [1932]. 437.CS1 maint: others (link)

- Tybjerg, Casper (2008). Visual Essay: Real and unreal (DVD). New York City: The Criterion Collection.

- Tybjerg, Casper (2008). Visual Essay: Vanished scenes (DVD). New York City, United States: The Criterion Collection.

- Vampyr (Booklet essay "Vampyr and the Vampire"). Carl Theodor Dreyer. New York, United States: The Criterion Collection. 2008 [1932]. 437.CS1 maint: others (link)

- Clarens, 1997. p. 107

- Kristel, Todd. "Vampyr > Review > AllMovie". AllMovie. Retrieved 14 July 2009.

- Rosenbaum, Jonathan. "Vampyr: Capsule by Jonathan Rosenbaum". Chicago Reader. Retrieved 14 July 2009.

- Vampyr (Booklet notes on the restoration of Dreyer's Vampyr). Carl Theodor Dreyer. New York, United States: The Criterion Collection. 2008 [1932]. 437.CS1 maint: others (link)

- Tybjerg, Casper (2008). Visual Essay: The ghostly presence (DVD). New York City, United States: The Criterion Collection.

- Kehr, Dave (22 July 2008). "New DVDs: 'Vampyr' and 'The Mummy'". The New York Times. Retrieved 14 July 2009.

- Truffaut 1994, p. 48.

- Hoberman, Jim (26 August 2008). "A Dreyer Duo – Day of Wrath at the IFC and Vampyr on DVD". The Village Voice. p. 2. Retrieved 14 July 2009.

- Steffen, James. "Vampyr". Turner Classic Movies. Retrieved 14 July 2009.

- "Vampyr". Rotten Tomatoes. Fandango. Retrieved 30 June 2019.

- Bitel, Anton. "Vampyr Movie review (1932) from Channel 4 Film". Channel 4. Retrieved 28 January 2010.

- "The 100 best horror films". Time Out. Retrieved 13 April 2014.

- CC. "The 100 best horror films: the list". Time Out. Retrieved 13 April 2014.

- McNally, 1994. p. 259

- Seibert, Perry. "Vampyr > Overview". AllMovie. Archived from the original on 19 April 2009. Retrieved 14 July 2009.

- "Image Entertainment / Foreign / Vampyr". Image Entertainment. Archived from the original on 23 October 2007. Retrieved 7 February 2011.

- "Masters of Cinema – Carl Dreyer DVDs". Masters of Cinema. Archived from the original on 1 July 2009. Retrieved 14 July 2009.

- "Vampyr [2 Disc] [Special Edition] [Criterion Collection] – allmovie". Allmovie. Archived from the original on 16 January 2013. Retrieved 14 July 2009.

- "The Strange Adventure of Allan Gray". Allmovie. Archived from the original on 16 January 2013. Retrieved 14 July 2009.

- "Vampyr / The Masters of Cinema Series". Eureka Video. Retrieved 14 July 2009.

- "Criterion Announces October Titles". Blu-ray.com. Retrieved 18 July 2017.

Bibliography

- Rudkin, David (2005). BFI Film Classics: Vampyr. BFI Publishing. ISBN 1-84457-073-8.

- Clarens, Carlos (1997). An Illustrated History of Horror and Science-fiction Films. Da Capo Press. ISBN 0-306-80800-5.

- McNally, Raymond T.; Radu Florescu (1994). In Search of Dracula: The History of Dracula and Vampires. Houghton Mifflin Harcourt. ISBN 0-395-65783-0.

- Truffaut, François; Leonard Mayhew (1994). The Films in my Life. Da Capo Press. ISBN 0-306-80599-5.

- Bazin, André; Jacques Doniel-Valcroze; Michel Delhaye (1999). Buñuel, Dreyer, Welles (in Spanish) (3rd ed.). Editorial Fundamentos. ISBN 84-245-0521-2. Retrieved 14 July 2009.

External links

- Vampyr on IMDb

- Vampyr at AllMovie

- Vampyr at the TCM Movie Database

- Vampyr is available for free download at the Internet Archive

- Vampyr is available for free download at the Internet Archive

- Vampyr at Rotten Tomatoes

- Vampyr: From Carmilla to Carl Dreyer at Teleport City

- Vampyr’s Ghosts and Demons an essay by Mark Le Fanu at the Criterion Collection