Yuri (genre)

Yuri (百合, "lily"), also known by the wasei-eigo construction Girls' Love (ガールズラブ, gāruzu rabu),[3] is a Japanese jargon term for content and a genre involving lesbian relationships or female homoeroticism in light novels, manga, anime, video games and related Japanese media.[4][5] Yuri focuses on the sexual orientation or the romantic orientation aspects of the relationship, or both, the latter of which is sometimes called shōjo-ai by Western fandom,[6] despite its different and negative meaning in actual Japanese.

The themes yuri deals with have their roots in the Japanese lesbian fiction of the early twentieth century,[7][8] with pieces such as Yaneura no Nishojo by Nobuko Yoshiya.[9] Nevertheless, it is not until the 1970s that lesbian-themed works began to appear in manga, by the hand of artists such as Ryoko Yamagishi and Riyoko Ikeda.[1] The 1990s brought new trends in manga and anime, as well as in dōjinshi productions, along with more acceptance for this kind of content.[10] In 2003, Japanese publisher Sun Magazine launched the first manga magazine specifically dedicated to yuri, titled Yuri Shimai; this was followed by its revival, Comic Yuri Hime, which was launched after the former was discontinued in 2004.[11][12]

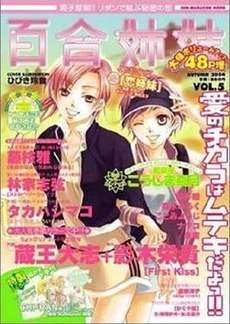

As a genre, yuri content does not inherently target a single gender demographic, unlike their counterparts yaoi and bara. Although yuri originated in female-targeted works, today it is also featured in male-targeted ones.[8] Yuri manga from male-targeted magazines include titles such as Kannazuki no Miko and Strawberry Panic!, as well as those from Comic Yuri Hime's male-targeted sister magazine, Comic Yuri Hime S, which was launched in 2007.[13]

Definition and semantic drift

Etymology

The word yuri (百合) literally means "lily", and is a relatively common Japanese feminine name.[4] In 1976, Bungaku Itō, editor of Barazoku (薔薇族, lit. "rose tribe"), a magazine geared primarily towards gay men, first used the term yurizoku (百合族, lit. "lily tribe") in reference to female readers in the title of a column of letters called Yurizoku no Heya (百合族の部屋, lit. "lily tribe's room").[14] It is unclear whether this was the first instance of this usage of the term. Not all women whose letters appeared in this short-lived column were necessarily lesbians, but some were and gradually an association developed. For example, the tanbi magazine Allan (アラン, Aran) began running a Yuri Tsūshin (百合通信, "Lily Communication") personal ad column in July 1983 for "lesbiennes" to communicate.[15] Along the way, many dōjinshi circles incorporated the name "Yuri" or "Yuriko" into lesbian-themed hentai (pornographic) dōjinshi, and the zoku or "tribe" portion of this word was subsequently dropped.[6] Since then, the meaning has drifted from its mostly pornographic connotation to describe the portrayal of intimate love, sex, or the intimate emotional connections between women.[16]

Japanese vs. Western usage

As of 2009, the term yuri is used in Japan to mean the depiction of attraction between women (whether sexual or romantic; explicit or implied) in manga, anime, and related entertainment media, as well as the genre of stories primarily dealing with this content.[5][16] The wasei-eigo construction "Girls Love" (ガールズラブ, gāruzu rabu), occasionally spelled "Girl's Love" or "Girls' Love", or abbreviated as "GL", is also used with this meaning.[3][16] Yuri is generally a form of fanspeak amongst fans, but its usage by authors and publishers has increased since 2005.[3][5] The term "Girls Love", on the other hand, is primarily used by the publishers.[16][17]

In North America, yuri had initially been used to denote only the most explicit end of the spectrum, deemed primarily as a variety of hentai.[6] Following the pattern of shōnen-ai, a term already in use in North America to describe content involving relationships between men which does not feature sexually explicit scenes, Western fans coined the term shōjo-ai to describe yuri without explicit sex.[6] In Japan, the term shōjo-ai (少女愛, lit. "girl love") is not used with this meaning,[6] and instead tends to denote pedophilia (actual or perceived), with a similar meaning to the term lolicon (Lolita complex).[18] The Western use of yuri has broadened in the 2000s, picking up connotations from the Japanese use.[16] American publishing companies such as ALC Publishing and Seven Seas Entertainment have also adopted the Japanese usage of the term to classify their yuri manga publications.[19][20]

Thematic history

Among the first Japanese authors to produce works about love between women was Nobuko Yoshiya,[9] a novelist active in the Taishō and Shōwa periods of Japan.[21] Yoshiya was a pioneer in Japanese lesbian literature, including the early twentieth century Class S genre.[22] These kinds of stories depict lesbian attachments as emotionally intense yet platonic relationships, destined to be curtailed by graduation from school, marriage, or death.[21] The root of this genre is in part the contemporary belief that same-sex love was a transitory and normal part of female development leading into heterosexuality and motherhood.[23] Class S stories in particular tell of strong emotional bonds between schoolgirls, a mutual crush between an upperclassman and an underclassman.[22]

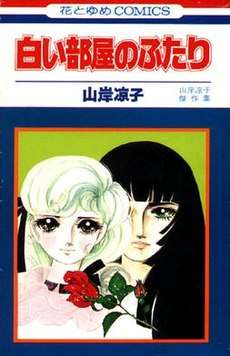

Around the 1970s, yuri began to appear in shōjo manga,[1] presenting some of the characteristics found in the lesbian literature of the early twentieth century.[7] This early yuri generally features an older looking, more sophisticated woman, and a younger, more awkward admirer. The two deal with some sort of unfortunate schism between their families, and when rumors of their lesbian relationship spread, they are received as a scandal. The outcome is a tragedy, with the more sophisticated girl somehow dying at the end.[7] In general, the yuri manga of this time could not avoid a tragic ending.[24][25] Ryoko Yamagishi's Shiroi Heya no Futari, the first manga involving a lesbian relationship,[1] is a prime example, as it was "prototypical" for many yuri stories of the 1970s and 1980s.[26] It is also in the 1970s that shōjo manga began to deal with transsexualism and transvestism,[27] sometimes depicting female characters as manly looking, which was inspired by the women playing male roles in the Takarazuka Revue.[28] These traits are most prominent in Riyoko Ikeda's works,[29] including The Rose of Versailles, Oniisama e..., and Claudine...![30] Some shōnen works of this period feature lesbian characters too, but these are mostly depicted as fanservice and comic relief.[31]

Some of these formulas began to weaken during the 1990s:[10] manga stories such as Jukkai me no Jukkai by Wakuni Akisato, published in 1992, began to move away from the tragic outcomes and stereotyped dynamics.[32] This stood side-by-side with dōjinshi works, which at the time were largely influenced by the immense popularity of Sailor Moon,[33] the first mainstream manga and anime series featuring a "positive" portrayal of an openly lesbian couple.[8][29] Furthermore, many of the people behind this show went on to make Revolutionary Girl Utena, a shōjo anime series where the main storyline focuses on a yuri relationship, which is widely regarded today as a masterpiece.[34] Male-targeted works such as the Devilman Lady anime series, based on a homonym seinen manga by Go Nagai, began to deal with lesbian themes in a more "mature manner" too.[35] The first magazines specifically targeted towards lesbians appeared around this period, containing sections featuring yuri manga.[36] These stories range from high school crush to lesbian life and love, featuring different degrees of sexual content.[36][37] It is at this point (the mid-1990s) that lesbian-themed works began to be acceptable.[29]

The later 1990s brought Oyuki Konno's Maria-sama ga Miteru, which by 2004 was a bestseller among yuri novels.[38] This story revisits what was being written at the time of Nobuko Yoshiya:[39] strong emotional bonds between females, mostly revolving around the school upperclassman-underclassman dynamic, like those portrayed in Class S.[39] Another prominent author of this period is Kaho Nakayama, active since the early 1990s, with works involving love stories among lesbians.[38]

Around the early 2000s, the first magazines specifically dedicated to yuri manga were launched,[11][12] containing stories dealing with a wide range of themes: from intense emotional connections such as that depicted in Voiceful, to more explicit school-girl romances like those portrayed in First Love Sisters,[40] and realistic tales about love between adult women such as those seen in Rakuen no Jōken.[41] Some of these subjects are seen in male-targeted works of this period as well,[42][43] sometimes in combination with other themes, including mecha and science fiction.[44][45] Examples include series such as Kannazuki no Miko, Blue Drop, and Kashimashi: Girl Meets Girl. In addition, male-targeted stories tend to make extensive use of moe and bishōjo characterizations.[13]

In the 2010s, yuri stories by lesbian creators became more prominent, such as My Lesbian Experience With Loneliness.[46]

Publications

Japanese

In the mid-1990s and early 2000s some Japanese lesbian lifestyle magazines contain manga sections, including the now-defunct magazines Anise (1996–97, 2001–03) and Phryné (1995).[36] Carmilla, an erotic lesbian publication,[36] released an anthology of lesbian manga called Girl's Only.[47] Additionally, Mist (1996–99), a ladies' comic manga magazine, contained sexually explicit lesbian-themed manga as part of a section dedicated to lesbian-interest topics.[36]

The first publication marketed exclusively as yuri was Sun Magazine's manga anthology magazine Yuri Shimai, which was released between June 2003 and November 2004 in quarterly installments, ending with only five issues.[11] After the magazine's discontinuation, Comic Yuri Hime was launched by Ichijinsha in July 2005 as a revival of the magazine,[5] containing manga by many of the authors who had had work serialized in Yuri Shimai.[12] Like its predecessor, Comic Yuri Hime was also published quarterly but went on to release bimonthly on odd months from January 2011 to December 2016, after which it became monthly.[12][48][49] A sister magazine to Comic Yuri Hime named Comic Yuri Hime S was launched as a quarterly publication by Ichijinsha in June 2007.[50] Unlike either Yuri Shimai or Comic Yuri Hime, Comic Yuri Hime S was targeted towards a male audience.[13] However, in 2010 it was merged with Comic Yuri Hime.[51] Ichijinsha published light novel adaptations from Comic Yuri Hime works and original yuri novels under their shōjo light novel line Ichijinsha Bunko Iris starting in July 2008.[52]

Once Comic Yuri Hime helped establish the market, several other yuri anthologies were released, such as Yuri Koi Girls Love Story, Hirari, Mebae, Yuri Drill, Yuri + Kanojo and Eclair.[53][54][55][56][57] Houbunsha also published their own yuri magazine, Tsubomi, from February 2009 to December 2012 for a total of 21 issues.[58][59] After a successful crowdfunding campaign, the creator-owned yuri anthology magazine Galette was launched in 2017.[60][61]

English

The first company to release lesbian-themed manga in North America was Yuricon's publishing arm ALC Publishing.[62] Their works include Rica Takashima's Rica 'tte Kanji!?—which in 2006 was course material for Professor Kerridwen Luis' Anthropology 166B course at Brandeis University[63][64]—and their annual yuri manga anthology Yuri Monogatari; both were first released in 2003.[62] The latter collects stories by American, European, and Japanese creators, including Akiko Morishima, Althea Keaton, Kristina Kolhi, Tomomi Nakasora, and Eriko Tadeno.[65][66] These works range from fantasy stories to more realistic tales dealing with themes such as coming out and sexual orientation.[66]

Besides ALC Publishing, the Los Angeles-based Seven Seas Entertainment has also incurred in the genre, with the English version of well known titles such as the Kashimashi: Girl Meets Girl manga and the Strawberry Panic! light novels.[20] On October 24, 2006, Seven Seas announced the launch of their specialized yuri manga line, which includes works such as the Strawberry Panic! manga, The Last Uniform,[20] and Comic Yuri Hime's compilations such as Voiceful and First Love Sisters.[40] Between 2011 and 2013, the now-defunct JManga released several yuri titles to its digital subscription platform, before terminating service on March 13, 2013.[67] As of 2017, Viz Media and Yen Press began publishing yuri manga,[68][69] with Tokyopop following in 2018.[70] Kodansha Comics announced its debut into publishing both yuri and yaoi manga in 2019, as well as Digital Manga launching a new imprint specializing in yuri dōjin manga.[71][72]

By the mid 2010s, yuri video games also began to be officially translated into English. In 2015, MangaGamer announced they would be releasing A Kiss for the Petals, the first license of a yuri game to have an English translation. MangaGamer went on to publish Kindred Spirits on the Roof in 2016, which was one of the first adult visual novels to be released uncensored on the Steam store.[73]

Outside Japan

As yuri gained further recognition outside Japan, some artists began creating original English-language manga that were labeled as yuri or having yuri elements and subplots. Early examples of original English-language yuri comics include Steady Beat by Rivkah LaFille and 12 Days by June Kim, which were published between 2005 and 2006. Additionally, more English-developed visual novels and indie games have marketed themselves as yuri games.[74] This has been aided by the Yuri Game Jam, a game jam established in 2015 that takes place annually.[75]

Demographics

A common misconception about demographics within yuri readership and viewers is that it must mirror the demographics of bara, meaning that just as bara is primarily made by and for gay men, yuri must be made primarily by and for lesbian women. However, while yuri does have its origins in female-targeted (shōjo, josei) works, the genre has evolved over time to also target a male audience.[76] Various studies have been done in Japan to try and determine what the typical profile of a yuri fan is.

Publishers' studies

The first magazine to study the demographics of its readers was Yuri Shimai (2003–2004), who estimated the proportion of women at almost 70%, and that the majority of them were either teenagers or women in their thirties who were already interested in shōjo and yaoi manga.[77] In 2008, Ichijinsha made a demographic study for its two magazines Comic Yuri Hime and Comic Yuri Hime S, the first being targeted to women, the second to men. The study reveals that women accounted for 73% of Comic Yuri Hime readership, while in Comic Yuri Hime S, men accounted for 62%. The publisher noted, however, that readers of the latter magazine also tended to read the first, which led to their merger in 2010.[51] Regarding the age of women for Comic Yuri Hime, 27% of them were under 20 years old, 27% between 20 and 24 years old, 23% between 25 and 29 years old, and 23% over 30 years old.[77] As of 2017, the ratio between men and women is said to have shifted to about 6:4, thanks in part to the Comic Yuri Hime S merge and the mostly male readership YuruYuri brought with it.[78]

Academic studies

Verena Maser conducted her own study of Japanese yuri fandom demographics between September and October 2011.[77] This study mainly oriented towards the Yuri Komyu! community and the Mixi social network, receiving a total of 1,352 valid responses. The study found that 52.4% of respondents were women, 46.1% were men and 1.6% did not identify with either gender. The sexuality of the participants was also requested, separated into two categories: "heterosexual" and "non-heterosexual". The results were as follows: 30% were non-heterosexual women, 15.2% were heterosexual women, 4.7% were non-heterosexual men, 39.5% were heterosexual men and 1.2% identified as "other". Regarding age, 69% of respondents were between 16 and 25 years old. Maser's study reinforced the notion of the yuri fandom being split somewhat equally between men and women, as well as highlighting the differing sexualities within it.

See also

Notes and references

- Brown, Rebecca (2005). "An Introduction to Yuri Manga and Anime (page 1)". AfterEllen.com. Archived from the original on March 3, 2007. Retrieved 2008-01-18.

- Friedman, Erica (2006-06-27). "Yuri Manga: Maya's Funeral Procession / Maya no Souretsu". Okazu. Yuricon. Archived from the original on 2015-07-03. Retrieved 2015-05-06.

- Morishima, Akiko (January 2008). "YurixYuri Kenbunroku". Comic Yuri Hime (in Japanese) (11). ASIN B00120LP56.

- Charlton, Sabdha. "Yuri Fandom on the Internet". Yuricon. Retrieved 2008-01-13.

- "Joseidōshi no LOVE wo egaita, danshi kinsei no "Yuri būmu" gayattekuru!?" (in Japanese). Cyzo. Archived from the original on 2012-07-03. Retrieved 2008-03-21.

- Friedman, Erica. "What are Yuri and Shoujoai, anyway?". Yuricon. Archived from the original on 6 April 2005. Retrieved 20 May 2005.

- Fujimoto, Yukari (1998). Watashi no Ibasho wa Doko ni Aruno? (Where do I belong?) (in Japanese). Tokyo: Gakuyo Shobo. ISBN 4-313-87011-3.

- "Interview: Erica Friedman". Manga. About.com. Archived from the original on 2016-03-04. Retrieved 2008-03-06.

- Tsuchiya, Hiromi (March 9–12, 2000). "Yoshiya Nobuko's Yaneura no nishojo (Two Virgins in the Attic): Female-Female Desire and Feminism". Homosexual/Homosocial Subtexts in Early 20th-Century Japanese Culture. San Diego, CA: Abstracts of the 2000 AAS Annual Meeting. Archived from the original on 2001-02-21. Retrieved 2008-02-24.

- "Maria-sama ga Miteru to Yuri Sakuhin no Rekishi" (in Japanese). Archived from the original on March 25, 2008. Retrieved 2008-02-16. Sources: Watashi no Ibasho wa Doko ni Aruno? by Yukari Fujimoto (ISBN 4313870113), Otoko Rashisa to Iu Byōki? Pop-Culture no Shin Danseigaku by Kazuo Kumada (ISBN 4833110679), and Yorinuki Dokusho Sōdanshitsu (ISBN 978-4860110345).

- "Yuri Shimai". ComiPedia. Archived from the original on 2011-07-22. Retrieved 2008-01-19.

- "Comic Yuri Hime". ComiPedia. Archived from the original on 2008-01-23. Retrieved 2015-04-04.

- "Ichijinsha's info about Comic Yuri Hime S" (in Japanese). Ichijinsha. Archived from the original on 2012-04-07. Retrieved 2008-01-03.

- "Yurizoku no Heya". Barazoku (in Japanese): 66–70. November 1976. After this first column, Yurizoku no Heya appeared sporadically through the mid-1980s.

- Welker, James (2008). "Lilies of the Margin: Beautiful Boys and Queer Female Identities in Japan". In Fran Martin; Peter Jackson; Audrey Yue (eds.). AsiaPacifQueer: Rethinking Genders and Sexualities. University of Illinois Press. pp. 46–66. ISBN 978-0-252-07507-0.

- "Interview: Erica Friedman (page 1)". Manga. About.com. Archived from the original on 2008-03-11. Retrieved 2008-05-17.

- "Comic Yuri Hime official website" (in Japanese). Ichijinsha. Archived from the original on 2008-01-21. Retrieved 2008-01-19. Ichijinsha classifies their yuri manga publication Comic Yuri Hime as a "Girls Love" comic magazine.

- Miyajima, Kagami (April 4, 2005). Shōjo-ai (in Japanese). Sakuhinsha. ISBN 4-86182-031-6.

- "ALC Publishing". Yuricon. Retrieved 2011-12-05.

- "Yuri on the Seven Seas!". Seven Seas Entertainment. Archived from the original on 2016-03-03. Retrieved 2007-11-20.

- Suzuki, Michiko (August 2006). "Writing Same-Sex Love: Sexology and Literary Representation in Yoshiya Nobuko's Early Fiction". The Journal of Asian Studies. 65 (3): 575. doi:10.1017/S0021911806001148.

- Robertson, Jennifer (August 1992). "The Politics of Androgyny in Japan: Sexuality and Subversion in the Theater and Beyond" (PDF). American Ethnologist (3 ed.). 19 (3): 427. doi:10.1525/ae.1992.19.3.02a00010. JSTOR 645194.

- Dollase, Hiromi (2003). "Early Twentieth Century Japanese Girls' Magazine Stories: Examining Shōjo Voice in Hanamonogatari (Flower Tales)". The Journal of Popular Culture. 36 (4): 724–755. doi:10.1111/1540-5931.00043. ISSN 0022-3840. OCLC 1754751.

- Natsume, Fusanosuke (1999). Manga no Yomikata (How to read manga). Tokyo: Takarajimasha.

- Schodt, Frederik (1996). Dreamland Japan: Writings on Modern Manga. Berkeley, CA: Stone Bridge Press. ISBN 978-1-880656-23-5.

- Welker, James (2006). "Drawing Out Lesbians: Blurred Representations of Lesbian Desire in Shōjo Manga". In Chandra, Subhash (ed.). Lesbian Voices: Canada and the World: Theory, Literature, Cinema. New Delhi: Allied Publishers Pvt. ISBN 81-8424-075-9.

- Thorn, Rachel Matt. "Unlikely Explorers: Alternative Narratives of Love, Sex, Gender, and Friendship in Japanese "Girls'" Comics". Archived from the original on 2008-02-12. Retrieved 2008-10-25.

- Welker, James (2006). "Beautiful, Borrowed, and Bent: "Boys' Love" as Girls' Love in Shōjo Manga". Signs: Journal of Women in Culture and Society. 31 (3): 841. doi:10.1086/498987.

- Subramian, Erin. "Women-loving Women in Modern Japan". Yuricon. Retrieved 2008-01-23.

- Corson, Suzanne (2007). "Yuricon Celebrates Lesbian Anime and Manga". AfterEllen.com. Archived from the original on March 23, 2008. Retrieved 2007-05-01.

- Ebiharai, Akiko (2002). "Japan's Feminist Fabulation: Reading Marginal with Unisex Reproduction as a Key Concept". Genders Journal (36). Archived from the original on 2015-10-04. Retrieved 2015-04-04.

- "Shōjo Yuri Manga Guide". Yuricon. Archived from the original on July 21, 2011. Retrieved June 2, 2011.

- Hayama, Torakichi. "What is Doujin?". Akiba Angels. Archived from the original on 2008-03-07. Retrieved 2008-03-07.

- Friedman, Erica (2007). "Erica Friedman's Guide to Yuri". AfterEllen.com. Archived from the original on March 29, 2008. Retrieved 2007-11-20.

- Huxley, John. "The Devil Lady Review". Anime Boredom. Archived from the original on 2008-07-05. Retrieved 2015-04-04.

- Welker, James; Suganuma, Katsuhiko (January 2006). "Celebrating Lesbian Sexuality: An Interview with Inoue Meimy, Editor of Japanese Lesbian Erotic Lifestyle Magazine Carmilla". Intersections: Gender, History and Culture in the Asian Context (12). Archived from the original on 2008-04-24. Retrieved 2008-01-30.

- "ALC Publishing announces yuri manga Works by Eriko Tadeno". Active Anime. Archived from the original on 2008-06-11. Retrieved 2008-02-24.Works by Eriko Tadeno is an anthology of four stories and three short gag comics that were originally published in Phryné, Anise and Mist magazines.

- Azuma, Erika (June 2004). Yorinuki Dokusho Sōdanshitsu (in Japanese). Hon no Zasshisha. ISBN 978-4-86011-034-5.

- "Esu toiu kankei". Bishōjo gaippai! Wakamono ga hamaru Marimite world no himitsu (in Japanese). Excite. Archived from the original on February 21, 2008. Retrieved 2008-03-05.

- "Newtype USA Reviews Voiceful and First Love Sisters Vol. 1". Seven Seas Entertainment. Archived from the original on 2008-01-28. Retrieved 2008-01-27.

- "Rakuen no Jōken" (in Japanese). Ichijinsha. Archived from the original on 2008-06-24. Retrieved 2015-04-04.

"Rakuen no Jouken / 楽園の条件". Okazu. Archived from the original on 2015-04-09. Retrieved 2015-04-04. - Rasmussen, David. "Kashimashi Review". Anime Boredom. Archived from the original on 2008-08-21. Retrieved 2015-04-04.

- Santos, Carlo (2008-02-05). "Right Turn Only!!". Anime News Network. Archived from the original on 2008-02-23. Retrieved 2008-02-28.

- "Kannazuki No Miko Reviews". Mania.com. Archived from the original on 2015-04-09. Retrieved 2015-04-04.

Friedman, Erica. "Kannazuki no Miko – New Yuri Anime Season Autumn 2004". Okazu. Archived from the original on 2015-04-09. Retrieved 2015-04-04. - "Yuri anime & gemu daitokushū". Comic Yuri Hime S (in Japanese) (2). September 2007. ASIN B000VWRJGU.

- "Rethinking Yuri: How Lesbian Mangaka Return the Genre to Its Roots". The Mary Sue. Archived from the original on September 18, 2018. Retrieved September 18, 2018.

- Girl's Only listing at Amazon.co.jp (in Japanese). ASIN 4780801079.

- "中村成太郎@百合姫+gateau". Ichijinsha (in Japanese). Twitter. Archived from the original on August 20, 2015. Retrieved July 29, 2015.

- "コミック百合姫2017年2月号" (in Japanese). Amazon. Retrieved November 21, 2016.

- "Comic Yuri Hime S". ComiPedia. Archived from the original on 2008-03-27. Retrieved 2015-04-04.

- "Comic Bunch, Comic Yuri Hime S Mags to End Publication". Anime News Network. June 18, 2010. Archived from the original on October 31, 2010. Retrieved November 8, 2010.

- "Ichijinsha Bunko Iris" (in Japanese). Ichijinsha. Archived from the original on 2008-06-23. Retrieved 2008-02-26.

- "Hirari, 2014 SPRING Vol. 13" (in Japanese). Shinshokan. Archived from the original on 2018-11-29. Retrieved 2019-03-03.

- Friedman, Erica. "Yuri Manga: Mebae, Volume 1". Okazu. Archived from the original on 2019-03-02. Retrieved 2019-03-03.

- Friedman, Erica. "Yuri Manga: Yuri Drill Anthology". Okazu. Archived from the original on 2019-03-06. Retrieved 2019-03-03.

- Friedman, Erica. "Yuri Anthology: Yuri + Kanojo". Okazu. Archived from the original on 2019-03-06. Retrieved 2019-03-03.

- Friedman, Erica. "Yuri Manga: Éclair Bleue: Anata ni Hibiku Yuri Anthology". Okazu. Archived from the original on 2019-03-06. Retrieved 2019-03-03.

- "Tsubomi Yuri Manga Magazine Ends Publication". Anime News Network. December 14, 2012. Archived from the original on September 24, 2015. Retrieved April 11, 2015.

- "Houbunsha to Launch Tsubomi Yuri Manga Anthology". Anime News Network. January 5, 2009. Archived from the original on September 24, 2015. Retrieved April 11, 2015.

- "Official website" (in Japanese). Galette Works. Archived from the original on 2019-03-05. Retrieved 2019-03-03.

- "ガレット創刊号" (in Japanese). Amazon.co.jp. Retrieved 2019-02-28.

- Font, Dillon. "Pro Amateur Comics – Yuri Doujinshi Rica 'tte Kanji!?". Animefringe. Archived from the original on 2016-03-03. Retrieved 2008-01-24.

- "Yuri Manga in Anthropology Course". Anime News Network. Archived from the original on 2008-03-05. Retrieved 2008-02-23.

- Luis, Kerridwen (December 20, 2005). "Syllabus Draft" (PDF). Unbounded Desires: A Cross-Cultural Look at Non-Heteronormative Sexualities Anth 166B. Brandeis University. Archived from the original (PDF) on June 9, 2008. Retrieved 2008-04-05.

- "ALC Publishing Presents Yuri Manga Anthology Yuri Monogatari 4". ComiPress. Archived from the original on 2011-07-23. Retrieved 2008-02-21.

- Thompson, Jason. "Falling for Manga! Part 1: A Quick-hit Guide to Autumn 2007's Hottest Manga". OtakuUSA. Archived from the original on 2008-06-22. Retrieved 2015-04-04.

- "JManga.com Retail/Viewing Service Termination and Refund Notice". March 13, 2013. Archived from the original on March 18, 2013. Retrieved March 13, 2013.

- "Viz Media Announces the Launch of New Yuri Manga Series Sweet Blue Flowers". Viz Media. Archived from the original on 2019-03-02. Retrieved 2019-02-21.

- "Yen Press Licenses Spirits & Cat Ears, A Kiss and White Lily for Her Manga". Anime News Network. Archived from the original on 2019-03-02. Retrieved 2019-02-21.

- "Tokyopop Restarts Manga Licensing With Konohana Kitan, Hanger, Futaribeya". Anime News Network. Archived from the original on 2019-03-01. Retrieved 2019-02-21.

- "New year, new yuri & BL! Featuring Yuri is My Job! Plus interview with Comic Yuri Hime's Editor-in-Chief!". Kodansha Comics. Archived from the original on 2019-03-02. Retrieved 2019-02-21.

- "Digital Manga Launches New Yuri Dōjin Label on May 1 (Updated)". Anime News Network. Archived from the original on 2019-04-27. Retrieved 2019-04-27.

- "Yuri Visual Novel Kindred Spirits on the Roof Out Now". Hardcore Gamer. February 12, 2016. Archived from the original on April 7, 2016. Retrieved March 26, 2016.

- "Top Games tagged Yuri". itch.io. Archived from the original on March 2, 2019. Retrieved February 28, 2019.

- "Yuri Game Jam". itch.io. Archived from the original on March 1, 2019. Retrieved February 28, 2019.

- Bauman, Nicki (February 12, 2020). "Yuri is for Everyone: An analysis of yuri demographics and readership". Anime Feminist. Retrieved May 9, 2020.

In reality, yuri has no homologous audience, and is not made primarily by or for men, women, straight people, queer people, or any other demographic. Throughout its 100-year history, the genre has uniquely evolved in and moved about multiple markets, often existing in many simultaneously. It is by and for a variety of people: men, women, heterosexuals, queer people, everyone!

- Maser, Verena (August 31, 2015). Beautiful and Innocent: Female Same-Sex Intimacy in the Japanese Yuri Genre (PhD). University of Trier. Archived from the original on November 2, 2018. Retrieved March 4, 2019.

- "きっかけは『ゆるゆり』! ブレイクする「百合」の魅力を専門誌編集長に聞いてみた。" (in Japanese). Kadokawa Corporation. December 6, 2017. Archived from the original on March 6, 2019. Retrieved March 4, 2019.

Further reading

- Nagaike, Kazumi (September 30, 2010). "The Sexual and Textual Politics of Japanese Lesbian Comics: Reading Romantic and Erotic Yuri Narratives". Electronic Journal of Contemporary Japanese Studies. Oita University Center for International Education and Research. Archived from the original on March 7, 2012. Retrieved July 18, 2013.

- Hemmann, Kathryn (2013). The Female Gaze in Contemporary Japanese Literature (Doctorate Thesis). University of Pennsylvania. Retrieved July 25, 2020.