Once Upon a Time in America

Once Upon a Time in America (Italian: C'era una volta in America) is a 1984 epic crime drama film co-written and directed by Italian filmmaker Sergio Leone and starring Robert De Niro and James Woods. The film is an Italian–American[3] venture produced by The Ladd Company, Embassy International Pictures, PSO Enterprises, and Rafran Cinematografica, and distributed by Warner Bros. Based on Harry Grey's novel The Hoods, it chronicles the lives of best friends David "Noodles" Aaronson and Maximilian "Max" Bercovicz as they lead a group of Jewish ghetto youths who rise to prominence as Jewish gangsters in New York City's world of organized crime. The film explores themes of childhood friendships, love, lust, greed, betrayal, loss, broken relationships, together with the rise of mobsters in American society.

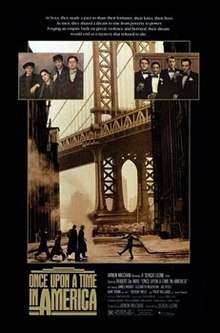

| Once Upon a Time in America | |

|---|---|

Theatrical release poster by Tom Jung | |

| Directed by | Sergio Leone |

| Produced by | Arnon Milchan |

| Screenplay by | |

| Based on | The Hoods by Harry Grey |

| Starring | |

| Music by | Ennio Morricone |

| Cinematography | Tonino Delli Colli |

| Edited by | Nino Baragli |

Production company |

|

| Distributed by |

|

Release date |

|

Running time | 250 minutes (Extended Cut) 229 minutes (Theatrical) 139 minutes (Re-edit) |

| Country | |

| Language | English |

| Budget | $30 million |

| Box office | $5.3 million[4] |

It was the final film directed by Leone before his death five years later, and the first feature film he had directed in 13 years. It is also the third film of Leone's Once Upon a Time Trilogy, which includes Once Upon a Time in the West (1968) and Duck, You Sucker! (1971).[5] The cinematography was by Tonino Delli Colli, and the film score by Ennio Morricone. Leone originally envisaged two three-hour films, then a single 269-minute (4 hours and 29 minutes) version, but was convinced by distributors to shorten it to 229 minutes (3 hours and 49 minutes). The American distributors, The Ladd Company, further shortened it to 139 minutes, and rearranged the scenes into chronological order, without Leone's involvement. The shortened version was a critical and commercial flop in the United States, and critics who had seen both versions harshly condemned the changes that were made. The original "European cut" has remained a critical favorite and frequently appears in lists of the greatest gangster films of all time.

Plot

Three thugs enter a Chinese wayang theater, looking for a marked man. The proprietors slip into a hidden opium den and warn a man named "Noodles", but he pays no attention. In a flashback, Noodles observes police removing three disfigured corpses from a street. Although he kills one of the thugs pursuing him, Noodles learns they have murdered Eve, his girlfriend, and that his money has been stolen, so he leaves the city.

David "Noodles" Aaronson struggles as a street kid in a neighborhood on Manhattan's Lower East Side in 1918. He and his friends Patrick "Patsy" Goldberg, Philip "Cockeye" Stein and Dominic commit petty crimes under the supervision of local boss, Bugsy. Planning to rob a drunk as a truck hides them from a police officer, they're foiled by Maximillian "Max" Bercovicz, who jumps off the truck to rob the man himself. Noodles confronts Max, but a crooked police officer steals the watch that they are fighting over. Later, Max blackmails the police officer, who is having sex with Peggy, a young girl and Noodles' neighbor. Max, Noodles, Patsy, Dominic and Cockeye start their own gang, independent of Bugsy, who had previously enjoyed the police officer's protection.

The boys stash half their money in a suitcase, which they hide in a locker at the railway station, giving the key to "Fat" Moe Gelly, a reliable friend who is not part of the operation. Noodles is in love with Fat Moe's sister, Deborah, an aspiring dancer and actress. After the gang has some success, Bugsy ambushes the boys and shoots Dominic, who dies in Noodles' arms. In a rage, Noodles stabs Bugsy and severely injures a police officer. He is arrested and sentenced to prison.

Noodles is released from jail in 1930 and is reunited with his old gang, who are now major bootleggers during Prohibition. Noodles also reunites with Deborah, seeking to rekindle their relationship. During a robbery, the gang meet Carol, who later on becomes Max's girlfriend. The gang prospers from bootlegging, while also providing muscle for union boss Jimmy Conway O'Donnell.

Noodles tries to impress Deborah on an extravagant date, but then rapes her after she declines his marriage proposal, as she intends to pursue a career in Hollywood. Noodles goes to the train station looking for Deborah, but when she spots him from her train seat, she simply closes the blind.

The gang's financial success ends with the 1933 repeal of Prohibition. Max suggests joining the Teamsters' union, as muscle, but Noodles refuses. Max acquiesces and they go to Florida, with Carol and Eve, for a vacation. While there, Max suggests robbing the New York Federal Reserve Bank, but Noodles regards it as a suicide mission.

Carol, who also fears for Max's life, convinces Noodles to inform the police about a lesser offense, so the four friends will safely serve a brief ("probably one year") jail sentence. Minutes after calling the police, Max knocks Noodles unconscious during an argument. Regaining consciousness, Noodles finds out that Max, Patsy, and Cockeye have been killed by the police, and is consumed with guilt over making the phone call. Noodles retrieves the suitcase in which the gang had stored their money, now finding it empty. With his friends killed, and himself hunted, a despondent Noodles then boards the first bus leaving New York, going to Buffalo, to live under a false identity, Robert Williams.

In 1968, Noodles receives a letter informing him that the cemetery where his friends are buried is being redeveloped, asking him to make arrangements for their reburial. Realizing that someone has deduced his identity, Noodles returns to Manhattan, and stays with Fat Moe above his restaurant. While visiting the cemetery, Noodles finds a key to the railway locker once kept by the gang. Opening the locker, he finds a suitcase full of money but with a note stating that the cash is a down-payment on his next job.

Noodles hears about a corruption scandal and assassination attempt on U.S. Secretary of Commerce Christopher Bailey, an embattled political figure, mentioned in a news report.

Noodles visits Carol, who lives at a retirement home run by the Bailey Foundation. She tells him that Max planted the idea of Carol and Noodles tipping him off to the police, because he wanted to die rather than go insane like his father, who died in an asylum; Max opened fire on the police to ensure his own death.

While at the retirement home, Noodles sees a photo of Deborah at the institution's dedication. Noodles tracks down Deborah, still an actress. He questions her about Secretary Bailey, telling her about his invitation to a party at Bailey's mansion. Deborah claims not to know who Bailey is and begs Noodles to leave via the back exit, as Bailey's son is waiting for her at the main door. Ignoring Deborah's advice, Noodles sees Bailey's son David, who is named after Noodles and bears a strong resemblance to Max as a young man. Thus, Noodles realizes that Max is alive and living as Bailey.

Noodles meets with Max in his private study during the party. Max explains that corrupt police officers helped him fake his own death, so that he could steal the gang's money and make Deborah his mistress in order to begin a new life as Bailey, a man with connections to the Teamsters' union, connections that have now gone sour.

Now faced with ruin and the specter of a Teamster assassination, Max asks Noodles to kill him, having tracked him down and sent the invitation. Noodles, obstinately referring to him by his Secretary Bailey identity, refuses because, in his eyes, Max died with the gang. As Noodles leaves Max's estate, he hears a garbage truck start up and looks back to see Max standing at his driveway's gated entrance. As he begins to walk towards Noodles, the truck passes between them. Noodles sees the truck's auger grinding down rubbish, but Max is nowhere to be seen.

The end returns to the opening scene in 1933, with Noodles entering the opium den after his friends' deaths, taking the drug and broadly grinning.

Cast

- Robert De Niro as Noodles

- Scott Tiler as Young Noodles

- James Woods as Max

- Rusty Jacobs as Young Max and David Bailey

- Elizabeth McGovern as Deborah

- Jennifer Connelly as Young Deborah

- Joe Pesci as Frankie Monaldi

- Burt Young as Joe

- Tuesday Weld as Carol

- Treat Williams as Jimmy O'Donnell

- Danny Aiello as Police Chief Aiello

- Richard Bright as Chicken Joe

- James Hayden as Patsy

- Brian Bloom as Young Patsy

- William Forsythe as Cockeye

- Adrian Curran as Young Cockeye

- Darlanne Fluegel as Eve

- Larry Rapp as Fat Moe

- Mike Monetti as Young Fat Moe

- Richard Foronji as Whitey

- Robert Harper as Sharkey

- Dutch Miller as Van Linden

- Gerard Murphy as Crowning

- Amy Ryder as Peggy

- Julie Cohen as Young Peggy

The cast also includes Noah Moazezi as Dominic, James Russo as Bugsy, producer Arnon Milchan as Noodles' chauffeur, Marcia Jean Kurtz as Max's mother, Estelle Harris as Peggy's mother, Joey Faye as an "Adorable Old Man", and Olga Karlatos as a wayang patron. Frank Gio, Ray Dittrich and Mario Brega (a regular supporting actor in Leone's Dollars Trilogy) respectively appear as Beefy, Trigger and Mandy, a trio of gangsters who search for Noodles. Frequent De Niro collaborator Chuck Low and Leone's daughter Francesca respectively make uncredited appearances as Fat Moe and Deborah's father, and David Bailey's girlfriend.[2] In the 2012 restoration, Louise Fletcher appears as the Cemetery Directress of Riverdale, where Noodles visits his friends' tomb in 1968.[6]

Production

Development

During the mid-1960s, Sergio Leone read the novel The Hoods by Harry Grey, a pseudonym for the former gangster-turned-informant whose real name was Harry Goldberg.[7] In 1968, after shooting Once Upon a Time in the West, Leone made many efforts to talk to Grey. Having enjoyed Leone's Dollars Trilogy, Grey finally responded and agreed to meet with Leone at a Manhattan bar.[8] Following that initial meeting, Leone met with Grey several times throughout the remainder of the 1960s and 1970s to understand America through Grey's point of view. Intent on making another trilogy about America consisting of Once Upon a Time in the West, Duck, You Sucker! and Once Upon a Time in America,[7] Leone turned down an offer from Paramount Pictures to direct The Godfather in order to pursue his pet project.[9][10]

Casting

Leone considered many actors for the film during the long development process. Originally, in 1975, Gérard Depardieu, who was determined to learn English with a Brooklyn accent for the role, was cast as Max, with Jean Gabin playing the older Max. Richard Dreyfuss was cast as Noodles, with James Cagney playing the older Noodles. In 1980, Leone spoke of casting Tom Berenger as Noodles, with Paul Newman playing the older Noodles. Among actors considered for the role of Max were Dustin Hoffman, Jon Voight, Harvey Keitel, John Malkovich, and John Belushi.

Early in 1981, Brooke Shields was offered the role of Deborah Gelly after Leone had seen The Blue Lagoon, saying that "she had the potential to play a mature character". A writers' strike delayed the project, and Shields withdrew before auditions began. Elizabeth McGovern was cast as Deborah and Jennifer Connelly as her younger self.

Joe Pesci was among many to audition for Max. He got the smaller role of Frankie, partly as a favor to his friend De Niro. Danny Aiello auditioned for several roles and was ultimately cast as the police chief who (coincidentally) shares his surname. Claudia Cardinale (who appeared in Once Upon a Time in the West) wanted to play Carol, but Leone was afraid she would not be convincing as a New Yorker and turned her down.

Filming

The film was shot between 14 June 1982, and 22 April 1983. Leone tried, as he had with Duck, You Sucker!, to produce the film with a young director under him. In the early days of the project he courted John Milius, a fan of his who was enthusiastic about the idea; but Milius was working on The Wind and the Lion and the script for Apocalypse Now and could not commit to the project. For the film's visual style, Leone used as references the paintings of such artists as Reginald Marsh, Edward Hopper, and Norman Rockwell, as well as (for the 1918 sequences) the photographs of Jacob Riis. F. Scott Fitzgerald's novel The Great Gatsby influenced Noodles' relationship with Deborah.

Most exteriors were shot in New York City (such as in Williamsburg along South 6th Street, where Fat Moe's restaurant was based, and South 8th Street), but several key scenes were shot elsewhere. Most interiors were shot in Cinecittà in Rome. The beach scene, where Max unveils his plan to rob the Federal Reserve, was shot at The Don CeSar in St. Pete Beach, Florida.[11] The New York's railway "Grand Central Station" scene in the thirties flashbacks was filmed in the Gare du Nord in Paris.[12] The interiors of the lavish restaurant where Noodles takes Deborah on their date were shot in the Hotel Excelsior in Venice, Italy.[12] The gang's hit on Joe was filmed in Quebec. The view of the Manhattan Bridge shown in the film's poster can be seen from Washington Street in Dumbo, Brooklyn.[13]

The shooting script, completed in October 1981 after many delays and a writers' strike between April and July of that year, was 317 pages in length.

Editing

By the end of filming, Leone had eight to ten hours worth of footage. With his editor, Nino Baragli, Leone trimmed this to almost six hours, and he originally wanted to release the film in two parts, each three hours.[14] The producers refused, partly because of the commercial and critical failure of Bernardo Bertolucci's two-part 1900, and Leone was forced to further shorten it.[14] The film was originally 269 minutes (4 hours and 29 minutes), but when the film premiered out of competition at the 1984 Cannes Film Festival,[15] Leone had cut it to 229 minutes (3 hours and 49 minutes) to appease the distributors, which was the version shown in European cinemas. However, the American wide release was edited further to 139 minutes (2 hours and 19 minutes) by the studio, against the director's wishes.

Music

The musical score was composed by Leone's longtime collaborator Ennio Morricone. The film's long production resulted in Morricone's finishing the composition of most of the soundtrack before many scenes had been filmed. Some of Morricone's pieces were played on set as filming took place, a technique that Leone had used for Once Upon a Time in the West. "Deborah's Theme" was written for another film in the 1970s but was rejected; Morricone presented the piece to Leone, who was initially reluctant to include it, considering it too similar to Morricone's main title music for Once Upon a Time in the West. The score is also notable for Morricone's incorporation of the music of Gheorghe Zamfir, who plays a pan flute. At times this music is used to convey remembrance, at other times terror. Zamfir's flute music was used to similarly haunting effect in Peter Weir's Picnic at Hanging Rock (1975).[16] Morricone also collaborated with vocalist Edda Dell'Orso on the score.

| Once Upon a Time in America | |

|---|---|

| Soundtrack album by | |

| Released | 1 June 1984 17 October 1995 (Special Edition) |

| Recorded | December 1983 |

| Studio | Forum Studios, Rome |

| Genre | Contemporary classical |

| Label | Mercury Records |

| Producer | Ennio Morricone |

| Special Edition cover | |

A soundtrack album was released in 1984 by Mercury Records.[17] This was followed by a special-edition release in 1995, featuring four additional tracks.[18]

| No. | Title | Length |

|---|---|---|

| 1. | "Once Upon a Time in America" | 2:11 |

| 2. | "Poverty" | 3:37 |

| 3. | "Deborah's Theme" | 4:24 |

| 4. | "Childhood Memories" | 3:22 |

| 5. | "Amapola" | 5:21 |

| 6. | "Friends" | 1:34 |

| 7. | "Prohibition Dirge" | 4:20 |

| No. | Title | Length |

|---|---|---|

| 8. | "Cockeye's Song" | 4:20 |

| 9. | "Amapola, Part II" | 3:07 |

| 10. | "Childhood Poverty" | 1:41 |

| 11. | "Photographic Memories" | 1:00 |

| 12. | "Friends" | 1:23 |

| 13. | "Friendship & Love" | 4:14 |

| 14. | "Speakeasy" | 2:21 |

| 15. | "Deborah's Theme – Amapola" | 6:13 |

| No. | Title | Length |

|---|---|---|

| 16. | "Suite from Once Upon a Time in America (Includes Amapola)" | 13:32 |

| 17. | "Poverty (Temp. Version)" | 3:26 |

| 18. | "Unused Theme" | 4:46 |

| 19. | "Unused Theme (Version 2)" | 3:38 |

Besides the original music, the film used source music, including:

- "God Bless America" (written by Irving Berlin, performed by Kate Smith – 1943) – Plays over the opening credits from a radio in Eve's bedroom and briefly at the film's ending.

- "Yesterday" (written by Lennon–McCartney – 1965) – A Muzak version of this piece plays when Noodles first returns to New York in 1968, examining himself in a train station mirror. An instrumental version of the song also plays briefly during the dialogue scene between Noodles and "Bailey" towards the end of the film.

- "Summertime" (written by George Gershwin – 1935) An instrumental version of the aria from the opera Porgy and Bess is playing softly in the background as Noodles, just before leaving, explains to "Secretary Bailey" why he could never kill his friend.

- "Amapola" (written by Joseph Lacalle, American lyrics by Albert Gamse – 1923) – Originally an opera piece, several instrumental versions of this song were played during the film; a jazzy version, which was played on the gramophone danced to by young Deborah in 1918; a similar version played by Fat Moe's jazz band in the speakeasy in 1930; and a string version, during Noodles' date with Deborah. It has been suggested that Leone used this piece after hearing a version of it in the film Carnal Knowledge, though this has not been confirmed. Both versions are available on the soundtrack.

- "La gazza ladra" overture (Gioachino Rossini – 1817) – Used during the famous baby-switching scene in the hospital.

- "Night and Day" (written and sung by Cole Porter – 1932) – Played by a jazz band during the beach scene before the beachgoers receive word of Prohibition's repeal, and during the party at the house of "Secretary Bailey" in 1968.

- "St. James Infirmary Blues" is used during the Prohibition "funeral" at the gang's speakeasy.

Release

Once Upon a Time in America premiered at the 1984 Cannes Film Festival on 23 May.[14][15] It received a raucous, record-breaking ovation of nearly 20 minutes after the screening (reportedly heard by diners at restaurants across the street from the Palais), at a time in Cannes's history before marathon applause became a regular occurrence.[19] In the United States, the film received a wide release in 894 theaters on 1 June 1984, and grossed $2.4 million during its opening weekend.[20] It ended its box office run with a gross of just over $5.3 million on a $30 million budget,[21] and became a box office flop.[22] The financial and critical disaster of the American release almost bankrupted The Ladd Company. Eventually, the film premiered in Leone's native Italy out of competition at the 41st Venice International Film Festival in September 1984.[23] That same month, the film was released wide in Italy on 28 September 1984, in its 229-minute version.

Versions

Several different versions of Once Upon a Time in America have been shown. The original European release version (1984, 229 minutes) was shown internationally.

US excisions

The film was shown in limited release and for film critics in North America, where it was slightly trimmed to secure an "R" rating. Cuts were made to two rape scenes and some of the more graphic violence at the beginning. Noodles' meeting with Bailey in 1968 was also excised. The film gained a mediocre reception at several sneak premieres in North America. Because of this early audience reaction, the fear of its length, its graphic violence, and the inability of theaters to have multiple showings in one day, the decision was made by The Ladd Company to make many edits and cut entire scenes without the supervision of Sergio Leone.[14] This American wide release (1984, 139 minutes) was drastically different from the European release, as the non-chronological story was rearranged into chronological order. Other major cuts involved many of the childhood sequences, making the adult 1933 sections more prominent. Noodles' 1968 meeting with Deborah was excised, and the scene with Bailey ends with him shooting himself (with the sound of a gunshot off screen) rather than the garbage truck conclusion of the 229-minute version.

USSR

In the Soviet Union, the film was shown theatrically in the late 1980s, with other Hollywood blockbusters such as the two King Kong films. The story was rearranged in chronological order and the film was split in two, with the two parts shown as separate movies,[24] one containing the childhood scenes and the other comprising the adulthood scenes. Despite the rearranging, no major scene deletions were made. It was rated "16+" by the Goskino.

TV compilation

A network television version was shown in the early to mid-1990s with a running time of almost three hours (excluding commercials). While it retained the film's original non-chronological order, many key scenes involving violence and graphic content were left out. This version was a one-off showing, and no copies are known to exist.

Restored original

In March 2011, it was announced that Leone's original 269-minute version was to be re-created by a film lab in Italy under the supervision of Leone's children, who had acquired the Italian distribution rights, and the film's original sound editor, Fausto Ancillai, for a premiere in 2012 at either the Cannes Film Festival or Venice Film Festival.[25][26]

The restored film premiered at the 2012 Cannes Film Festival, but because of unforeseen rights issues for the deleted scenes, the restoration had a runtime of only 251 minutes.[27][28][29] However, Martin Scorsese (whose Film Foundation helped with the restoration) stated that he is helping Leone's children gain the rights to the final 24 minutes of deleted scenes to create a complete restoration of Leone's envisaged 269-minute version. On 3 August 2012, it was reported that after the premiere at Cannes, the restored film was pulled from circulation, pending further restoration work.[30]

Home media

In North America, a two-tape VHS was released by Warner Home Video with a runtime of 226 minutes in February 1985 and 1991. The U.S. theatrical cut was also released at the same time in February 1985.[31] A two-disc special edition was released on 10 June 2003, featuring the 229-minute version of the film.[32] This special edition was rereleased on 11 January 2011, on both DVD and Blu-ray.[33] On 30 September 2014, Warner Bros. released a two-disc Blu-ray and DVD set of the 251-minute restoration shown at the 2012 Cannes Film Festival, dubbed the Extended Director's Cut.[34] This version was previously released in Italy, on 4 September 2012.[35]

Critical reception

The initial critical response to Once Upon a Time in America was mixed, because of the different versions released worldwide. While internationally the film was well received in its original form, American critics were much more dissatisfied with the 139-minute version released in North America. This condensed version was a critical and financial disaster, and many American critics who knew of Leone's original cut attacked the short version. Some critics compared shortening the film to shortening Richard Wagner's operas, saying that works of art that are meant to be long should be given the respect they deserve. Roger Ebert wrote in his 1984 review that the uncut version was "an epic poem of violence and greed" but described the American theatrical version as a "travesty".[36] Ebert gave the uncut version a full four stars while giving the American theatrical version one star.[37] Ebert's television film critic partner Gene Siskel considered the uncut version to be the best film of 1984 and the shortened, linear studio version to be the worst film of 1984.[38]

It was only after Leone's death and the subsequent restoration of the original version that critics began to give it the kind of praise displayed at its original Cannes showing. The uncut original film is considered to be far superior to the edited version released in the US in 1984.[39] Ebert, in his review of Brian De Palma's The Untouchables, called the original uncut version of Once Upon a Time in America the best film depicting the Prohibition era.[40] James Woods, who considers it to be Leone's finest film, mentioned in the DVD documentary that one critic dubbed the film the worst of 1984, only to see the original cut years later and call it the best of the 1980s.[24] The review aggregator website Rotten Tomatoes reports an 86% approval rating with an average rating of 8.62/10 based on 50 reviews. The website's consensus reads, "Sergio Leone's epic crime drama is visually stunning, stylistically bold, and emotionally haunting, and filled with great performances from the likes of Robert De Niro and James Woods."[41]

The film has since been ranked as one of the best films of the gangster genre. When Sight & Sound asked several UK critics in 2002 what their favorite films of the last 25 years were, Once Upon a Time in America placed at number 10.[42] In 2015, the film was ranked at number nine on Time Out's list of the 50 best gangster films of all time.[43]

Interpretations

As the film begins and ends in 1933, with Noodles hiding in an opium den from syndicate hitmen, and the last shot of the film is of Noodles in a smiling, opium-soaked high, the film can be interpreted as having been a drug-induced dream, with Noodles remembering his past and envisioning the future. In an interview by Noël Simsolo published in 1987, Leone confirms the validity of this interpretation, saying that the scenes set in the 1960s could be seen as an opium dream of Noodles'.[44] In the DVD commentary for the film, film historian and critic Richard Schickel states that opium users often report vivid dreams, and that these visions have a tendency to explore the user's past and future.[45]

Many people (including Schickel) assume that the 1968 Frisbee scene, which has an immediate cut and gives no further resolution, was part of a longer sequence.[46] Ebert stated that the purpose of the flying disc scene was to establish the 1960s time frame and nothing more.[36]

Accolades

Despite its modern critical success, the initial American release did not fare well with critics and received no Academy Award nominations.[47] The film's music was disqualified from Oscar consideration for a technicality,[48] as the studio accidentally omitted the composer's name from the opening credits when trimming its running time for the American release.[24]

| Award | Category | Nominee | Result |

|---|---|---|---|

| 38th British Academy Film Awards[49] | Best Costume Design | Gabriella Pescucci | Won |

| Best Film Music | Ennio Morricone | Won | |

| Best Direction | Sergio Leone | Nominated | |

| Best Actress in a Supporting Role | Tuesday Weld | Nominated | |

| Best Cinematography | Tonino Delli Colli | Nominated | |

| 42nd Golden Globe Awards[50] | Best Director | Sergio Leone | Nominated |

| Best Original Score | Ennio Morricone | Nominated | |

| 8th Japan Academy Prize[51] | Outstanding Foreign Language Film | Won | |

| 10th Los Angeles Film Critics Association Awards[52] | Best Film | Nominated | |

| Best Director | Sergio Leone | Nominated | |

| Best Music Score | Ennio Morricone | Won |

References

- "Once Upon a Time in America". Trove. Archived from the original on 12 October 2016. Retrieved 11 October 2016.

- "Once upon a Time in America (1983)". British Film Institute. Retrieved 1 February 2020.

- "Once Upon a Time in America (EN) [Original title]". European Audiovisual Observatory. Archived from the original on 24 June 2018. Retrieved 17 February 2016.

- "Once Upon a Time in America (1984) - Box Office Mojo". www.boxofficemojo.com. Archived from the original on 29 September 2019. Retrieved 22 October 2019.

- "The film with three names – in praise of Sergio Leone's neglected spaghetti western". British Film Institute. 24 April 2018. Archived from the original on 2 June 2019. Retrieved 2 June 2019.

- Macnab, Geoffrey (15 May 2012). "Martin Scorsese breathes new life into gangster classic Once Upon a Time in America". The Independent. Archived from the original on 2 April 2015. Retrieved 26 March 2015.

- Hughes Crime Wave: The Filmgoers' guide to the great crime movies pp. 156–157.

- Frayling, Christopher (1 July 2000). Sergio Leone: Something to Do with Death (PDF). London: Faber and Faber. pp. 388–392. Archived from the original (PDF) on 5 March 2016. Retrieved 27 March 2015.

- Roger Fristoe. "Sergio Leone Profile". Turner Classic Movies. Archived from the original on 16 July 2014. Retrieved 25 March 2015.

- Lucia Bozzola. "Sergio Leone". The New York Times. Archived from the original on 16 July 2014. Retrieved 25 March 2015.

- "History of Loews Don CeSar Hotel". Loews Hotels. Archived from the original on 21 November 2015. Retrieved 29 March 2015.

- "The Worldwide Guide to Movie Locations". Archived from the original on 11 December 2010. Retrieved 14 January 2011.

- "Google Maps". Google Maps. Retrieved 22 October 2019.

- Hughes Crimewave: The Filmgoers' guide to the great crime movies p. 163.

- "Festival de Cannes: Once Upon a Time in America". festival-cannes.com. Retrieved 25 June 2009.

- Other reviews by Messrob Torikian (25 August 2003). "Once Upon a Time in America (1984)". Soundtrack. Archived from the original on 7 October 2012. Retrieved 19 May 2012.

- "Once Upon a Time in America (1984) Soundtrack". Soundtrack.Net. Archived from the original on 2 April 2015. Retrieved 24 March 2015.

- "Once Upon a Time in America [Special Edition] – Ennio Morricone". AllMusic. All Media Network. Archived from the original on 22 November 2015. Retrieved 24 March 2015.

- https://mauiwatch.com/2019/05/a-rons-film-rewind-presents-once-upon-a-time-in-america-the-35th-anniversary/

- "Once Upon a Time in America". Box Office Mojo. IMDb. Archived from the original on 2 April 2015. Retrieved 26 March 2015.

- "Once Upon a Time in America". The Numbers. Archived from the original on 2 April 2015. Retrieved 26 March 2015.

- McCarty, John (24 May 2005). Bullets Over Hollywood: The American Gangster Picture from the Silents to "The Sopranos". Boston, Massachusetts: Da Capo Press. p. 235. Archived from the original on 10 April 2016. Retrieved 26 March 2015.

- "History of the Venice Film Festival: The 1980's". Carnival of Venice. Archived from the original on 23 September 2015. Retrieved 27 March 2015.

- Once Upon a Time: Sergio Leone (Documentary) (in English and Italian). CreaTVty, Westbrook. 8 January 2001.

- Variety (10 March 2011): "'Once Upon a Time' to be restored" Retrieved 21 April 2011

- The Film Forum (13 Mar 2011): "Once Upon a Time in America – 269 minute version in 2012" Archived 10 June 2011 at the Wayback Machine Retrieved 21 April 2011

- Barraclough, Leo (16 May 2012). "Another chance for 'Once' – Entertainment News, Film Festivals, Media". Variety. Archived from the original on 10 November 2012. Retrieved 19 May 2012.

- Gallman, Brett (21 April 2012). "'Once Upon a Time in America,' Other Director's Cuts Worth Watching". Movies.yahoo.com. Archived from the original on 9 July 2012. Retrieved 19 May 2012.

- Cannes Classics 2012 – Festival de Cannes 2014 (International Film Festival) Archived 15 February 2017 at the Wayback Machine. Festival-cannes.fr. Retrieved on 5 June 2014.

- Paley, Tony (3 August 2012). "Sergio Leone's Once Upon a Time in America is withdrawn from circulation". The Guardian. London. Archived from the original on 14 February 2017. Retrieved 12 December 2016.

- "Two Homevid Versions Of 'America'". Daily Variety. 18 December 1984. p. 21.

- Erickson, Glenn (June 2003). "DVD Savant Review: Once Upon a Time in America". DVD Talk. Archived from the original on 17 November 2014. Retrieved 26 March 2015.

- "Once Upon a Time in America Preview". IGN. Ziff Davis. 11 January 2011. Archived from the original on 3 April 2015. Retrieved 26 March 2015.

- "Once Upon a Time in America: Extended Director's Cut Blu-ray". Blu-ray.com. 5 June 2014. Archived from the original on 7 June 2014. Retrieved 5 June 2014.

- "Once Upon a Time in America (Comparison)". Movie-Censorship.com. 11 December 2012. Archived from the original on 2 April 2015. Retrieved 26 March 2015.

- Ebert, Roger (1 January 1984). "Once Upon A Time in America". Chicago Sun-Times. Archived from the original on 2 May 2013. Retrieved 8 June 2008.

- Ebert, Roger. ""Siskel and Ebert" You Blew It, 1990". Retrieved 8 August 2020.

- Siskel, Gene. ""Siskel and Ebert" Top Ten Films (1980–1998)". Estate of Gene Siskel. Archived from the original on 23 February 2010. Retrieved 27 March 2015.

- Turan, Kenneth (10 July 1999). "A Cinematic Rarity: Showing of Leone's Uncut 'America'". The Los Angeles Times. Archived from the original on 3 February 2016. Retrieved 3 February 2016.

- Ebert, Roger (3 June 1987). "The Untouchables (1987)". Chicago Sun-Times. Archived from the original on 4 February 2017. Retrieved 27 March 2015.

- "Once Upon a Time in America". Rotten Tomatoes. Fandango Media. Archived from the original on 23 May 2019. Retrieved 10 July 2019.

- "Modern Times". Sight & Sound. British Film Institute. December 2002. Archived from the original on 7 March 2012. Retrieved 27 March 2015.

- "The 50 best gangster movies of all time". Time Out. Time Out Limited. 12 March 2015. p. 5. Archived from the original on 15 March 2015. Retrieved 27 March 2015.

- Simsolo, Noël (1987). Conversations avec Sergio Leone. Paris: Stock. ISBN 2-234-02049-2.

- Once Upon a Time in America commentary with film historian Richard Schickel

- Once Upon a Time in America DVD audio commentary

- "Snubbed by Oscar: Mistakes & Omissions". AMC Networks. American Movie Classics Company. Archived from the original on 17 March 2015. Retrieved 27 March 2015.

- Ibid

- "Film in 1985". British Academy of Film and Television Arts. Archived from the original on 2 May 2013. Retrieved 25 March 2015.

- Thomas, Bob (8 January 1985). "Amadeus," The Killing Fields," Top Nominees". Associated Press Archive. Associated Press. Archived from the original on 27 March 2015. Retrieved 27 March 2015.

- "8th Japan Academy Prize". Japan Academy Prize Association (in Japanese). Archived from the original on 15 March 2015. Retrieved 27 March 2015.

- "10th Annual Los Angeles Film Critics Association Awards". Los Angeles Film Critics Association. 2007. Archived from the original on 18 January 2015. Retrieved 27 March 2015.

Bibliography

- Hughes, Howard (2002). Crime Wave: The Filmgoers' guide to the great crime movies.