Gangster film

A gangster film or gangster movie is a film belonging to a genre that focuses on gangs and organized crime. It is a subgenre of crime film, that may involve large criminal organizations, or small gangs formed to perform a certain illegal act. The genre is differentiated from Westerns and the gangs of that genre.

Overview

The American Film Institute defines the genre as "centered on organized crime or maverick criminals in a twentieth century setting".[1] The institute named it one of the 10 "classic genres" in its 10 Top 10 list, released in 2008. The list recognizes 3 films from 1931 & 1932 (Scarface, The Public Enemy & Little Caesar). Only 1 film made the list from 1933 to 1966, (White Heat (1949)). This was at least partly due to the limitations on the genre imposed by the Hays Code, which was finally abandoned in favor of the Motion Picture Association of America film rating system in 1968.[2]

The genre was revitalized in the New Hollywood movement that followed. New Hollywood directors would be honored with 5 of the top 6 films on the list—1967's Bonnie and Clyde by Arthur Penn, 1972's The Godfather and 1974's The Godfather Part II both by Francis Ford Coppola, 1983's Scarface, a remake of the 1932 original, by Brian De Palma, and 1990's Goodfellas by Martin Scorsese.

In the 1970s, as genre theory came to the focus of academic study and the creation of a more specific taxonomy of genres was defined, gangster film started being distinguished from other subgenres, especially that of western. The genre has been predominantly defined by its historical, ideological, and sociocultural context.[3] Three main categories of gangster films can be distinguished, according to Martha Nochimson: films that follow the escapades of outlaw rebels, such as Bonnie and Clyde, melodramas of villain gangsters against whom the in-story victims and the audience identify, such as Key Largo and, most predominantly in the genre, films following an outsider, immigrant gangster protagonist, with whom the audience identifies.[4]

The first Japanese films about the Yakuza evolved from the Tendency films of the 1930s. They featured historical tales of outlaws and the abuses suffered by the common people often at the hands of the corrupt powers that be.[5] The so-called "Chivalry movies" of the 1960s gave way to the violent realism of Kinji Fukasaku, whose 1973 Battles Without Honor and Humanity would inspire future filmmakers across the globe.

Gangster films in the United States

Early Hollywood

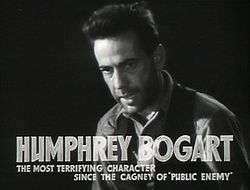

1931 and 1932 produced three of the most enduring gangster films ever. Scarface, Little Caesar and The Public Enemy remain as three of the greatest examples of the genre. However, starting in the mid-1930s, the Hays Code and its requirements for all criminal action to be punished and all authority figures to be treated with respect made gangster films scarce for the next three decades.

Politics combined with the social and economic climate of the time to influence how crime films were made and how the characters were portrayed. Many of the films imply that criminals are the creation of society, rather than its rebel,[6] and considering the troublesome and bleak time of the 1930s, that argument carries significant weight. Often the best of the gangster films are those that have been closely tied to the reality of crime, reflecting public interest in a particular aspect of criminal activity; thus, the gangster film is in a sense a history of crime in the United States.[7]

The institution of Prohibition in 1920 led to an explosion in crime, and the depiction of bootlegging is a frequent occurrence in many mob films. However, as the 1930s progressed, Hollywood also experimented with the stories of the rural criminals and bank robbers, such as John Dillinger, Baby Face Nelson, and Pretty Boy Floyd. The success of these characters in film can be attributed to their value as news subjects, as their exploits often thrilled the people of a nation who had become weary with inefficient government and apathy in business.[8] However, as the FBI increased in power there was also a shift to favour the stories of the FBI agents hunting the criminals instead of focusing on the criminal characters. In fact, in 1935 at the height of the hunt for Dillinger, the Production Code office issued an order that no film should be made about Dillinger for fear of further glamorizing his character.

Many of the 1930s crime films also dealt with class and ethnic conflict, notably the earliest films, reflecting doubts about how well the American system was working. As stated, many films pushed the message that criminals were the result of a poor moral and economic society, and many are portrayed as having foreign backgrounds or coming from the lower class. Thus, the film criminal is often able to evoke sympathy and admiration out of the viewer, who often place the blame on not the criminal's shoulders but a cruel society in which success is difficult.[9] When the decade came to a close, crime films became more figurative, representing metaphors, as opposed to the more straight forward films produced earlier in the decade, showing an increasing interest in offering a thought provoking message about criminal character.[10]

New Hollywood

.jpg)

With the abolition of the Hays Code in the late 1960s, studios and filmmakers found themselves free to produce films dealing with subject matter that had previously been off-limits.[2] Early examples include Arthur Penn's depression-era tale of Bonnie and Clyde; Mean Streets, Scorsese's cinema vérité story of a young aspiring mobster and his problem-gambler friend, played by Robert De Niro and Sam Peckinpah's Bring Me the Head of Alfredo Garcia, about the Mexican mob, family honor, and the opportunistic Bennie (Warren Oates), friend of the eponymous Alfredo Garcia, looking to make a big score when the chance drops in his lap. Bonnie and Clyde was one of 1967's biggest box office hit and garnered 2 Academy Awards and 8 other nominations including best picture. It, along with the others, however, were overshadowed by Francis Ford Coppola Godfather saga.

The Godfather pioneering Italian-American Mafia films

In 1972, Francis Ford Coppola's The Godfather was released. The epic story of the Corleone family, its generational transition from post-prohibition to post-war, its fratricidal intrigues, and its tapestry of mid-century America's criminal underworld became a huge critical and commercial success. It accounted for nearly 10% of gross proceeds for all films for the entire year.[11] It won the Oscar for Best Picture, as well as the award for Best Actor for Marlon Brando[12] and is widely considered one of the greatest American films of all time. Two years later, The Godfather Part II became the fifth-highest-grossing film of the year and garnered 11 Academy Award nominations. It again won Best Picture. Coppola won Best Director and Robert De Niro won best supporting actor for his portrayal of a young Vito Corleone.

The lesson of the films' successes was not wasted on Hollywood. Throughout the 1970s and 1980s, the studios issued a steady flow of films about Italian American gangsters and the Mafia. Some of these were critically acclaimed. Scorsese's Goodfellas about Henry Hill's life and relationship with the Lucchese and Gambino crime families, was nominated for 6 Academy Awards, including Best Picture and Best Director and won the award for Best Supporting Actor for Joe Pesci's performance. Others, however, strayed into stereotypes and the gratuitous use of Italian ethnicity in minor characters who happened to be criminals. This created a backlash in the Italian American community.[13]

Scorsese and the 1990s–2010s

The films of the 1990s produced several critically acclaimed mob films, many of which were loosely based on real crimes and their perpetrators. Many of these films featured long-time actors well known for their roles as mobsters such as Al Pacino, Robert De Niro, Joe Pesci and Chazz Palminteri.

Goodfellas, directed by Martin Scorsese, starred Ray Liotta as real-life associate of the Lucchese crime family Henry Hill. It was one of the most notable gangster films of the decade. Robert De Niro and Joe Pesci also starred in the film with Pesci earning an Academy Award for Best Actor in a Supporting Role. The film was nominated for six Academy Awards in all, including Best Picture and Best Director, making Goodfellas one of the most critically acclaimed crime films of all time.

Following their collaboration in Goodfellas, Scorsese, De Niro and Pesci would team up again in 1995's Casino, based on Frank Rosenthal, an associate of the Chicago Outfit, that ran multiple casinos in Las Vegas during the 1970s and 1980s. The film was De Niro's third mob film of the decade, following Goodfellas (1990) and A Bronx Tale (1993).

Al Pacino also returned to the genre during the 1990s. He reprised his role as the iconic Michael Corleone in The Godfather Part III (1990). The film served as the final installment in The Godfather trilogy, following Michael Corleone as he tries to legitimize the Corleone family in the twilight of his career.

In 1993, Pacino starred in Carlito's Way as a former gangster released from prison that vows to go straight. In 1996, Armand Assante starred in television film Gotti as infamous New York mobster, John Gotti. In 1997's Donnie Brasco, Pacino starred alongside Johnny Depp in the true story of undercover FBI agent Joseph Pistone and his infiltration of the Bonanno crime family of New York City during the 1970s. It was nominated for an Academy Award for Best Adapted Screenplay.

In 2006, Scorsese released The Departed, his adaptation of Infernal affairs, the Hong Kong film. The Departed was also loosely based on the Whitey Bulger story, and Boston's Winter Hill Gang, which Bulger led. It earned Scorsese an Academy Award for Best Director and the film won the Academy Award for Best Picture.

A 2018 biographical mafia film, Gotti, directed by Kevin Connolly, stars John Travolta as John Gotti, released in June. On review aggregator Rotten Tomatoes, the film holds an approval rating of 0% based on 38 reviews, and an average rating of 2.3/10. The website's critical consensus reads, "Fuhgeddaboudit."[14] In 2019, Martin Scorsese released a biographical mafia film through Netflix, The Irishman, starring all three heavyweights in the genre, Robert De Niro as Frank "The Irishman" Sheeran, Al Pacino as Jimmy Hoffa and Joe Pesci as Russell Bufalino.

2020s

The Many Saints of Newark is an upcoming American crime drama film directed by Alan Taylor and produced by David Chase and Lawrence Konner, as a prequel to Chase's HBO crime drama series The Sopranos, which is widely regarded as one of the greatest television series of all time. The film will also center around the fictional New Jersey-based Dimeo crime family.

African Americans

Apart from telling their own Tales of African American gangsters in syndicates, films like Black Caesar feature the Italian mafia prominently. Often the blaxploitation stories of the seventies tell the tale of African American gangsters rising up and defeating the established white criminal order. [15]African Americans were under-looked in the cinema world in the 20th century due to racism. African Americans didn't have a chance to tell their stories about their communities in Hollywood. It took African American Movie producers/Directors to actually tell stories about their communities. Movie directors and Producers like John Singleton, Spike Lee, Hughes Brothers made movies in the 90s explaining lifestyle in Urban Communities. Drugs, gang culture, gang violence, racism and poverty in African American communities were told by these producers/directors. [16]Boyz N The Hood, Menace II Society, Do The Right Thing were all examples of movies made by these names telling stories about urban African American life. One of the most famous African American gangster films is John Singleton’s Boyz N The Hood. [17]This movie takes place in South Central Los Angeles. Boyz In The Hood tells a story of Trey Styles who was living with his mother in South Central, Los Angeles, Tre’s mother moved her son to live with his father in Crenshaw where Tre can learn how to be a man, Crenshaw is a community in South Central, Los Angeles where its full of drugs, police brutality, gang culture, gang violence, and the famous war between two African American Gangs, Bloods and Crips. Before Gangster films were telling stories about life in the urban communities but telling stories about mafia, the mob and organized crime that would happen during those times. African Americans didn't have their part of the spotlight during those times. [16]African Americans would have a chance later in the 20th century to tell story about crime and social issues in their Communities.

- Blaxsploitation

- 1990s

Cocaine and the cartels

Brian De Palma's 1983 remake of Scarface stars Al Pacino as Tony Montana, a Cuban exile and ambitious newcomer to Miami who sees an opportunity to build his own drug empire. Abel Ferrara's 1990 King of New York tells the story of Frank White, (Christopher Walken) and his return to New York City from prison. He navigates both the traditional Italian mafia authorities as well as the new cartels, as they are producing, smuggling and distributing cocaine in an uneasy business Alliance.

- Blow

- Traffic

Latino gang films

- Boulevard Nights (1979)

- Walk Proud (1979)

- Zoot Suit (film) (1981)

- American Me (1992)

- Blood In Blood Out (1993)

- Carlito's Way (1993)

- Mi Vida Loca (1994)

- My Family (film) (1995)

Japan and the Yakuza

Early films about the Yakuza revolved around pre-war notions of honor and loyalty. These ninkyo eiga (chivalry films) were replaced in the late 1960s and early 1970s by a new style, pioneered by Kinji Fukasaku and inspired by the French New Wave and American Film noir called Jitsuroku eiga (true record films).[18] The new style is considered to have begun with Fukasaku's Battles Without Honor and Humanity (1972), a violent, realistic portrayal of post-war gangs in the ruins of Hiroshima. In addition to Fukasaku's "shaky camera style", this new brand of film often adapted true stories.

Prior to Battles, the films of Seijun Suzuki had departed from the ninkyo eiga formula, but had met with limited commercial success. Although, Suzuki's Branded to Kill would later inspire other directors in the gangster film genre, including John Woo, Chan-wook Park and Quentin Tarantino.[19]

Italian-made gangster films

- The Bankers of God: The Calvi Affair

- Belluscone: A Sicilian Story

- The Big Family

- Biùtiful cauntri

- Black City

- Black Turin

- Blood Ties

- Il Boss

- Caliber 9

- Camorra

- Il camorrista

- Canne mozze

- Il Capo dei Capi

- A Children's Story

- The City Stands Trial

- Confessions of a Police Captain

- The Consequences of Love

- Contraband

- Corleone

- The Day of the Owl

- Il Divo

- Excellent Cadavers

- Fort Apache Napoli

- From Corleone to Brooklyn

- Gang War

- Gang War in Naples

- Giovanni Falcone

- Gomorrah

- I guappi

- How to Kill a Judge

- Illustrious Corpses

- In the Name of the Law

- The Italian Connection

- Johnny Stecchino

- The Legendary Giulia and Other Miracles

- Mafia and Red Tomatoes

- Mafia Connection

- The Mafia Kills Only in Summer

- Mafioso

- The Man of Glass

- The Mattei Affair

- Napoli violenta

- The New Godfathers

- One Hundred Days in Palermo

- One Hundred Steps

- The Palermo Connection

- The Payoff

- La piovra

- Red Moon

- The Repenter

- Romanzo Criminale

- Salvatore Giuliano

- Sacred Silence

- Secret File

- Tatanka

- The Sicilian Girl

- The Sicilian

- La sfida

- Sgarro alla camorra

- Suburra

- Turri il bandito

- Vento del sud

- We Still Kill the Old Way

- Weapons of Death

- Where's Picone?

British gangster films

The 1947 adaptation of the Graham Greene novel by the same name, Brighton Rock, is a stark portrayal of a young gang leader and the racketeers in Brighton. It has been recognized as one of the greatest UK films ever by the British Film Institute.

- Kray Twins#In popular culture (active in the 1950s and 1960s)

- The Krays (film) (1990)

- The Rise of the Krays (2015)

- Legend (2015 film)

- The Fall of the Krays (2016)

- Get Carter (1971)

- The Long Good Friday (1980)

- Mona Lisa (1986 film) (1986)

- Stormy Monday (film) (1988)

- Face (1997 film)

- Lock, Stock and Two Smoking Barrels (1998)

- Essex Boys (2000)

- Gangster No. 1 (2000)

- Love, Honour and Obey (2000)

- Sexy Beast (2000)

- Snatch (film) (2000)

- I'll Sleep When I'm Dead (film) (2003)

- Layer Cake (film) (2004)

- The Business (film) (2005)

- A Very British Gangster (2006) - documentary

- Eastern Promises (2007) - Russian Mafia in the UK

- RocknRolla (2008)

- Dead Man Running (2009)

- Down Terrace (2009)

- London Boulevard (2010)

- The Wee Man (2013) - Scottish gangster film

- We Still Kill the Old Way (2014 film)

French gangster films

An early example of the Gallic gangster film is Maurice Tourneur’s 1935 film Justin de Marseille set in Marseille. Tourneur's gangster-hero differentiates from his American equivalent by valuing honour, artisanship, community and solidarity.[20] Four years before of the rise of film noir, in 1937, Julien Duvivier creates Pépé le Moko, a French gangster film in the style of poetic realism that takes place in the Casbah. Its distribution in America was blocked by the US-makers of its 1938 remake Algiers.[21] French gangster films will appear again in the mid-1950s, most notably Jacques Becker's Touchez pas au grisbi, American blacklisted filmmaker Jules Dassin's Rififi and Jean-Pierre Melville's Bob le flambeur.

1969 and 1970 saw the release of three successful French gangster films featuring the day's biggest French movie stars. All three films featured Alain Delon. Jean Gabin, Delon, and Lino Ventura starred in 1969's Le clan des siciliens, about a jewel thief and the Mafia. Borsalino, a tale of the Italian Mafia in 1930 Marseilles, also featured Delon, along with Jean-Paul Belmondo. In Le Cercle Rouge, Delon, Gian Maria Volonté, and Yves Montand team up to rob an impenetrable jewelry store.

All three of the films were domestic successes and Borsalino was popular elsewhere in Europe. None of them, however, broke through in the United States.

Indian cinema

Indian cinema, including Bollywood, has several genres of gangster films.

- Dacoit films, a genre about dacoit gangs in rural India. The genre often draws inspiration from real dacoits. Examples:

- Aurat (1940)

- Mother India (1957)

- Gunga Jumna (1961)

- Sholay (1975)

- Bandit Queen (1994)

- Mumbai underworld films, a genre about the Mumbai underworld (formerly the Bombay underworld), gangs hailing from the urban slums of Mumbai (formerly Bombay). The genre often draws inspiration from real Mumbai underworld gangsters, such as Haji Mastan, Dawood Ibrahim and D-Company. Examples:

- Zanjeer (1973)

- Deewaar (1975)

- Don franchise (1978–2012)

- Nayakan (1986)

- Salaam Bombay! (1988)

- Aryan (1988)

- Parinda (1989)

- Abhimanyu (1991)

- Baashha (1995)

- Satya (1998)

- Company (2002)

- Black Friday (2004)

- Slumdog Millionaire (2008), a film inspired by Mumbai underworld films from Indian cinema.

- Once Upon a Time in Mumbaai (2010) and Once Upon ay Time in Mumbai Dobaara! (2013)

- Gangs of Wasseypur series (2012), based on the Mafia Raj.

- Aaaranya kaandam (2010),Tamil neo noir gangster film which was based on north madras crimes.

- Subramaniapuram (2008), Film Based on real life events in Madurai.

- Pudhupettai (2006), Tamil neo noir gangster film written and directed by Selvaraghavan.

- Kammatipaadam (2016), Malayalam gangster film by Rajeev Ravi about the land mafia in Ernakulam

- Vikram Vedha (2017), Tamil language neo noir thriller directed by Pushkar-Gayatri based on vikramadityan vedhalam folk tale.

- Vada Chennai (2018), Tamil gangster film by Vetrimaran about the north madras people and their lifestyle

- om (1995),Kannada movie written and directed by upendra explores Bangalore underworld and mafia.[22]

- Ugramm is a Kannada

film which explores the gangster genre with World-building themes and revenge

Hong Kong

The Hong Kong gangster film genre began with 1986's A Better Tomorrow, directed by John Woo and starring Chow Yun Fat.[23] Woo's tale of counterfeiters portrays a gangster who balances "Kung Fu honor" and the materialistic goals of the Triads.[23] It was the all-time biggest grossing Hong Kong film at the box office and was critically acclaimed. Woo would follow with a string of successes, including The Killer, Bullet in the Head, and Hard Boiled.

- Gun fu

- Heroic bloodshed

- A Better Tomorrow (1986)

- City on Fire (1987)

- The Killer (1989)

- To Be Number One (film) (1991)

- Infernal Affairs (2002)

Russian cinema

Soviet propaganda has always said that organized crime exists only in the West. However, with the dissolution of the Soviet Union, people of Russia had to face the fact of what they used to previously read only in newspapers. Gang wars accompanied the formation of capitalism in Russia. This decade in Russia received the name of "Dashing 90s" (Russian: Лихие 90-е, translit. Lihie devyanostye).[24]

In 1997 director Aleksei Balabanov released Brother which acquired cult status and started to return interest of local people to Russian cinema, which had been in crisis since the early 1990s. Later came the sequel Brother 2 (2000), which was even more successful. Actor Sergei Bodrov Jr., who played a major role in both of those films, in 2001 released Sisters, which was his directorial debut. Other notable films of those years were Antikiller (2002) by Yegor Konchalovsky and Tycoon (2002) by Pavel Lungin.[24][25]

Pyotr Buslov, a young 26-year-old director, in 2003 released Bimmer, which instantly became a hit. This movie about four friends was made in the road movie style. A few years later, Buslov released the sequel Bimmer 2 (2006). In 2005 Aleksei Balabanov returned to the theme of gangster cinema and filmed a black comedy Dead Man's Bluff. Later Balabanov returned to the theme of bandits again in The Stoker (2010). In 2010 was also released The Alien Girl by Anton Bormatov.[24]

Russian television shows a lot of series about bandits, however, they are mostly of poor quality. A great success was the mini-series Brigada (2002), which received cult status.[24]

Comedy and parodies

See also

References

- "American Film Institute Brings The Best Of Hollywood Together To Celebrate "Afi'S 10 Top 10" On The Cbs Television Network, June 17, 2008" (PDF) (Press release). Los Angeles: American Film Institute. American Film Institute (AFI). 29 May 2008. Archived from the original (PDF) on 28 March 2014. Retrieved 2017-06-27.

- Cortés, Carlos E. (1987). "Italian-Americans in Film: From Immigrants to Icons". MELUS. 14 (3/4): 117. doi:10.2307/467405. JSTOR 467405.

- Mason, Fran (2012). "Gangster Films". Oxford Bibliographies. doi:10.1093/obo/9780199791286-0102. Retrieved 29 June 2017.

- Lam, Anita (2016-11-22). "Gangsters and Genre". Oxford Research Encyclopedias: Criminology and Criminal Justice. doi:10.1093/acrefore/9780190264079.013.149. ISBN 9780190264079. Retrieved 27 June 2017.

- Thornton, S.A. (30 October 2007). "5. The Yakuza Film". The Japanese Period Film: A Critical Analysis. McFarland. pp. 94–95. ISBN 978-0-7864-3136-6. Retrieved 28 June 2017.

- John Baxter, The Gangster Film (London: C. Tinling and Co. Ltd, 1970), p. 7.

- Baxter, p. 7.

- Baxter, p. 9.

- Terry Christensen, Projecting Politics: Political Messages in American Films (New York: M.E. Sharp, Inc., 2006), p. 77

- Christensen, p. 79.

- Schatz, Thomas (2004). "The New Hollywood". Hollywood: Critical Concepts in Media and Cultural Studies. Motion Picture Industry. I. Taylor & Francis. pp. 292–293. ISBN 978-0-415-28132-4.

- Brando declined the Oscar in protest of Hollywood's treatment of Native Americans. "43 years later, Native American activist Sacheen Littlefeather reflects on rejecting Marlon Brando's Oscar". 27 February 2016. Retrieved 3 July 2017.

- Cortés, Carlos E. (1987). "Italian-Americans in Film: From Immigrants to Icons". MELUS. 14 (3/4): 118–119. doi:10.2307/467405. JSTOR 467405.

- "Gotti (2018)". Rotten Tomatoes. Fandango Media. Retrieved June 28, 2018.

- Masswood, Paula. Black City Cinema.

- Masswod, Paula. Black City Cinema.

- Singleton, John, 1968-2019, screenwriter. film director. Nicolaides, Steve, film producer. Fishburne, Laurence, III, 1961- actor. Ice Cube (Musician), actor. Gooding, Cuba, Jr., 1968- actor. Long, Nia. actor. Chestnut, Morris. actor. Ferrell, Tyra. actor. Bassett, Angela. actor. King, Meta. actor. Mayo, Whitman, 1930-2001, actor. Clarke, Stanley. composer (expression), Boyz n the hood, OCLC 773206256CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)

- Sharp, Jasper (13 October 2011). "Fukasaku Shinji". Historical Dictionary of Japanese Cinema. United Kingdom: Scarecrow Press. pp. 64–65. ISBN 978-0-8108-7541-8. Retrieved 27 June 2017.

- Kermode, Mark (July 2006). "Well, I told you she was different ..." The Guardian. Guardian Unlimited. Archived from the original on 2007-12-01. Retrieved 2007-04-13.

- David Pettersen (2017). "Maurice Tourneur's Justin de Marseille (1935): transatlantic influences on the French gangster". Studies in French Cinema. 17: 1–20. doi:10.1080/14715880.2016.1213586.

- Matthew Thrift. "Ten great French gangster films". bfi.org.uk. Retrieved 27 June 2017.

- "25 years of 'Om': Top five reasons why you should watch Shivarajkumar and Prema's classic film". The Times of India. 2020-05-19. Retrieved 2020-08-09.

- Martha Nochimson (21 May 2007). Dying to Belong: Gangster Movies in Hollywood and Hong Kong. United Kingdom: Blackwell Publishing. p. 75. ISBN 978-1-4051-6370-5. Retrieved 3 July 2017.

- ""Кино бандитское". Несправедливо короткая история одного нерожденного жанра". TheSpot.ru. February 18, 2011. Retrieved May 18, 2019.

- Khazaradze, Salome (October 5, 2014). "14 Essential Films For An Introduction To Post-Soviet Russian Cinema". Taste of Cinema. Retrieved May 18, 2019.

Bibliography

- Film Study: An Analytical Bibliography, Volume 1

- Gangster, Detective, Crime, and Mystery Films: A Bibliography of Materials in the UC Berkeley Library

- Cortés, Carlos E. “Italian-Americans in Film: From Immigrants to Icons.” MELUS, vol. 14, no. 3/4, 1987, pp. 107–126. JSTOR, www.jstor.org/stable/467405.

- Schatz, Thomas (2004). "The New Hollywood". Hollywood: Critical Concepts in Media and Cultural Studies. Motion Picture Industry. I. Taylor & Francis. pp. 292–293. ISBN 978-0-415-28132-4.

Further reading

- Gangster Films at oxfordbibliographies.com

- Exploring the South African gangster film genre prior and post liberation: a study of Mapantsula, Hijack Stories and Jerusalema

- Researcher studies a century's worth of gangsters in film, TV - K.U. School of the Arts

- Paris, city of shadows: French crime cinema before the New Wave

- Gangster film: Glasgow's Traditional Identities (available pages: 155-158)

- The Gangster Film: Fatal Success in American Cinema

- Melodramas Of Ethnicity And Masculinity: Generic Transformations Of Late Twentieth Century American Film Gangsters by Larissa Ennis

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Gangster films. |