Shame (1968 film)

Shame (Swedish: Skammen) is a 1968 Swedish drama film written and directed by Ingmar Bergman, and starring Liv Ullmann and Max von Sydow. Ullmann and von Sydow play Eva and Jan, a politically uninvolved couple and former violinists whose home comes under threat by civil war. They are accused by one side of sympathy for the enemy, and their relationship deteriorates while the couple flees. The story explores themes of shame, moral decline, self-loathing and violence.

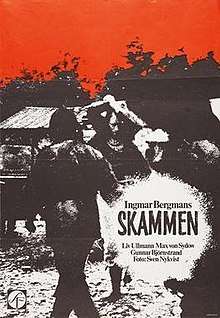

| Shame | |

|---|---|

Theatrical poster | |

| Directed by | Ingmar Bergman |

| Written by | Ingmar Bergman |

| Starring | Liv Ullmann Max von Sydow Sigge Fürst Gunnar Björnstrand Ulf Johansson |

| Cinematography | Sven Nykvist |

| Edited by | Ulla Ryghe |

Production company | Cinematograph AB |

| Distributed by | Svensk Filmindustri (Sweden) Lopert Pictures Corporation (USA) |

Release date |

|

Running time | 103 minutes |

| Country | Sweden |

| Language | Swedish |

| Box office | $250,000 (US)[1] |

The film was shot on Fårö, beginning in 1967, employing miniature models for the combat scenes. Shame was shot and released during the Vietnam War, although Bergman denied it was a commentary on the real-life conflict. He instead expressed interest in telling the story of a "little war".

Shame won a few honors, including for Ullmann's performance. It is sometimes considered the second in a series of thematically-related films, preceded by Bergman's 1968 Hour of the Wolf, and followed by the 1969 The Passion of Anna.

Plot

A husband and wife, Jan and Eva, are former violinists who are living on a farm on a rural island during a civil war. Their radio and telephone do not work, and Eva expresses frustration with Jan's apparent preference of escapism from the conflict, while they debate whether they can have children and if Jan is selfish. The couple visit the town, and hear a rumor that troops will soon come, and meet with an older man who has been called to duty.

When they return, their home area is bombed, and they see a parachutist descend on it. Jan and Eva are captured by the invading force and interviewed by a military journalist on camera, for a segment on the viewpoints of the "liberated" population. Eva initially seems indifferent to the conflict, but denies neutrality, and Jan declines to speak, and they are released. They are later captured again, and as soldiers interrogate them, the troops play a film of the interview, in which Eva's words have been dubbed over with incriminating speech. This is primarily a scare tactic.

Eventually, they are released by Col. Jacobi, who had formerly served as the mayor. After the couple returns home, their relationship is strained. Jacobi becomes a regular, if not uncomfortably constant, visitor who treats them with gifts but also has the power to send the couple to a work camp. This relationship is manipulative. Jacobi convinces Eva to provide him with sexual favors in exchange for his bank account savings. They go into the green house to have sex while Jan is resting. He wakes, calling Eva's name. Eventually, he goes upstairs and finds Jacobi's savings on the bed and begins to cry. Eva enters, while Jacobi stays outside and turns to leave. She then comments to a weeping Jan that he can continue sobbing if he feels it will help. Soldiers arrive, and Jacobi explains his freedom can be bought, as the side of the war who is here is in desperate need of money. Jacobi, the soldiers, and Eva ask Jan for the money. Jan states he does not know what money they are talking about. The soldiers raid the house to look for it, in vain. They hand Jan a gun to execute Jacobi, and he does. After the soldiers leave, Jan reveals he had the money in his pocket, to Eva's disgust. This has split their relationship irreparably and causes repeated breakdowns. The relationship grows silent and cold. When Jan and Eva meet a young soldier, Eva wants to feed him and allow him to sleep. Jan violently takes him away to shoot and rob him.

Eva follows Jan towards the sea, and he uses the money from Jacobi in order to buy them seats on a fishing boat. While at sea, the boat's motor fails. The man steering the boat kills himself by lowering himself overboard. The boat later finds itself stuck in the middle of floating dead bodies, unable to move forward and continue. As the boat takes away the refugees, Eva tells Jan of her dream: she walks down a beautiful city street with a shaded park, until planes come and set fire to the city and its rose vines. She and Jan have had a daughter, whom she is holding in her arms. They watch the roses burn, which she states "wasn't awful because it was so beautiful". She feels she had to remember something, but couldn't.

Cast

- Liv Ullmann – Eva Rosenberg

- Max von Sydow – Jan Rosenberg

- Sigge Fürst – Filip

- Gunnar Björnstrand – Col. Jacobi

- Birgitta Valberg – Mrs. Jacobi

- Hans Alfredson – Lobelius

- Ingvar Kjellson – Oswald

- Frank Sundström – Chief interrogator

- Ulf Johansson – The doctor

- Vilgot Sjöman – The interviewer

- Bengt Eklund – Guard

- Gösta Prüzelius – The vicar

- Willy Peters – Elder officer

- Barbro Hiort af Ornäs – Woman in the boat

- Agda Helin – Merchant's wife

Themes

Author Jerry Vermilye wrote that in exploring "the thread of violence intruding on ordinary lives", Hour of the Wolf (1968), Shame and The Passion of Anna represent a trilogy.[2] Author Amir Cohen-Shalev concurred the films form a trilogy.[3] In particular, Shame depicts the "disintegration of humanity in war".[4] The violence, which author Tarja Laine believed represented a civil war in Sweden, is depicted as "apparently meaningless".[5] Marc Gervais writes Shame, as a war film, does not address what either of the two sides of the war stand for, and does not venture into propaganda or a statement against totalitarianism, instead focusing on "human disintegration, this time extending it to a broader social dimension in the life of one small community".[6] The film delves into the concept of shame, associating it with the "moral failure with the self" bringing about a "traumatic configuration" in character, with Von Sydow's character developing from coward to murderer.[5]

Journalist Camilla Lundberg observed a pattern in Bergman's films that the protagonists are often musicians, though in an interview Bergman claimed he was not aware of such a trend.[7] Author Per F. Broman believed Shame fits this trend in that the characters are violinists, but remarked that music did not seem very relevant to the plot.[7] Laine suggested memories of playing the violin represent an "if-only" theme, in which the characters imagine a better life they could have had.[8] Cohen-Shalev wrote that, like Persona and The Passion of Anna, Shame follows an "artist as fugitive" theme touching on issues of guilt and self-hatred.[3]

Critic Renata Adler believed that "The 'Shame' of the title is God's".[9] However, other authors believe the film differs from Bergman's earlier works, inasmuch as it is less concerned with God.[10][11][12]

Production

Development

Ingmar Bergman wrote the screenplay for Shame, completing it in spring 1967.[13] He explained the origin of the story:

For a long time before making this film I had carried around the notion of trying to focus on the 'little war', the war that exist on the periphery where there is total confusion, and nobody knows what is actually going on. If I had been more patient when writing the script, I would have depicted this 'little war' in a better way. I did not have that patience.[14]

The controversial Vietnam War was being fought at the time, and while Bergman denied the film was a statement on the conflict, he remarked that "Privately, my view of the war in Vietnam is clear. The war should have been over a long time ago and the Americans gone".[15] He also stated "As an artist, I am horror-stricken by what is happening in the world".[10] He envisioned Jan and Eva as Social Democrats since that party subsidized culture.[15]

Filming

Shooting began in September 1967.[13] The film was shot on the island of Fårö, where the filmmakers had a house built to portray the Rosenberg residence.[16] The war scenes required trompe-l'œil effects, with Bergman and cinematographer Sven Nykvist burning miniature churches and making small streams look like violent rivers.[17] Nykvist also employed a substantial number of shots with hand-held cameras and zoom lenses.[15] Another location was Visby in Gotland; filming wrapped on 23 November.[18]

After shooting completed, Fårö's environmental regulations required the Rosenberg house be burned, but Bergman had developed an attachment to its appearance and saved it by claiming there were plans to use it in another film.[16] He began writing The Passion of Anna, and with Von Sydow and Ullmann still contracted to work with him, envisioned The Passion of Anna as "virtually a sequel".[16]

Release

The film had its debut in the International Cinema Incontri in Sorrento, Italy, which Bergman could not attend due to an ear infection.[10] It opened in Stockholm on 29 September 1968.[18]

In North America, Skammen was released under the title Shame.[19] It opened in New York City on 12 December 1968.[18] MGM released Shame on DVD both in the U.S. and the U.K. as part of a box set including Hour of the Wolf, The Passion of Anna, The Serpent's Egg and Persona, though the U.K. box set omits Persona.[20] The Criterion Collection announced a Blu-ray release in Region A for 20 November 2018, along with 38 other Bergman films, in the set Ingmar Bergman's Cinema.[21]

Reception

Critical reception

In Sweden, Mauritz Edström wrote in Dagens Nyheter that the film signified Bergman dealing less with his own inner conflict to something more contemporary and more important than one person.[14] Torsten Bergmark, also in Dagens Nyheter, wrote Bergman had found a new message, one of how a person without religion, Jan in this case, is left with self-loathing, while Eva is Bergman's "new solidarity".[22]

In the United States, Pauline Kael reviewed the film in The New Yorker in December 1968. She was an admirer of the film, writing "Shame is a masterpiece, ... a vision of the effect of war on two people". She praised Liv Ullmann as "superb in the demanding central role" and Gunnar Björnstrand as "beautifully restrained as an aging man clinging to the wreckage of his life".[23] Renata Adler, writing for The New York Times, called it "Dry, beautifully photographed, almost arid in its inspiration".[9] Judith Crist of New York called it "Bergman's definitive apocalyptic vision, painful and powerful". However, Crist added the kind of people who could learn from it did not usually watch Bergman films.[24]

In 2008, Roger Ebert gave Shame four stars, noting its timing during the Vietnam War and calling it "angry and bleak film that was against all war" and "a portrait of a couple torn from their secure lives and forced into a horrifying new world of despair". However, he remarked the film was less remembered than other Bergman films at the time of his writing.[25] In 2015, Drew Hunt of the Chicago Reader placed it in Bergman's top five films, judging it "A war film that's not actually about war".[26] The film has a 65% approval rating on Rotten Tomatoes, based on 17 reviews with an average rating of 6.9/10.[27]

Accolades

The film was selected as the Swedish entry for the Best Foreign Language Film at the 41st Academy Awards, but was not accepted as a nominee.[28] Liv Ullmann won the award for Best Actress at the 6th Guldbagge Awards.[29]

| Award | Date of ceremony | Category | Recipient(s) | Result | Ref(s) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Golden Globes | 24 February 1969 | Best Foreign Language Film | Shame | Nominated | [30] |

| Guldbagge Awards | 13 October 1969 | Best Actress | Liv Ullmann | Won | [29] |

| National Board of Review | 10 January 1969 | Best Actress | Won | [31] | |

| 1 January 1970 | Best Foreign Language Film | Shame | Won | [32] | |

| Top Foreign Films | Won | ||||

| National Society of Film Critics | January 1969 | Best Film | Won | [33] | |

| Best Director | Ingmar Bergman | Won | |||

| Best Screenplay | Runner-up | ||||

| Best Actress | Liv Ullmann | Won | |||

| Best Cinematography | Sven Nykvist | Runner-up | |||

See also

- List of submissions to the 41st Academy Awards for Best Foreign Language Film

- List of Swedish submissions for the Academy Award for Best Foreign Language Film

References

- Balio 1987, p. 231.

- Vermilye 2002, p. 133.

- Cohen-Shalev 2002, p. 138.

- Laine 2008, p. 60.

- Laine 2008, p. 61.

- Gervais 1999, p. 108.

- Broman 2008, p. 17.

- Laine 2008, p. 63.

- Adler, Renata (24 December 1968). "Shame". The New York Times. The New York Times Company. Retrieved 12 November 2016.

- Vermilye 2002, p. 128.

- Bergom-Larsson 1978, p. 101.

- Winter et al. 2007, p. 42.

- Marker & Marker 1992, p. 300.

- "Shame". Ingmar Bergman Foundation. Retrieved 13 November 2016.

- Ford, Hamish (March 2014). "Shame". Senses of Cinema (70). Retrieved 13 November 2016.

- Gado 1986, p. 377.

- Macnab 2009, p. 1.

- Steene 2005, p. 283.

- Vermilye 2002, p. 130.

- "Hour of the Wolf (1968)". AllMovie. RhythmOne. Retrieved 20 August 2015.

- Chitwood, Adam (12 July 2018). "Criterion Announces Massive 39-Film Ingmar Bergman Blu-ray Collection". Collider.com. Retrieved 15 July 2018.

- Steene 2005, p. 285.

- Kael 2011.

- Crist, Judith (13 January 1969). "Bergman's Basic Truth". New York. Vol. 2 no. 2. New York Media. p. 54. Retrieved 11 July 2018.

- Ebert, Roger (4 August 2008). "Shame". RogerEbert.com. Ebert Digital LLC. Retrieved 12 November 2016.

- Hunt, Drew (19 July 2015). "Ingmar Bergman's five best films". Chicago Reader. Retrieved 13 November 2016.

- "Skammen (Shame) (1968)". Rotten Tomatoes. Fandango Media. Retrieved 11 July 2018.

- Margaret Herrick Library, Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences

- "Shame (1968)". Swedish Film Database. Swedish Film Institute. Retrieved 2 March 2014.

- "Skammen". Golden Globe Awards. Hollywood Foreign Press Association. Retrieved 12 November 2016.

- "1968 Award Winners". National Board of Review. Retrieved 12 November 2016.

- "1969 Award Winners". National Board of Review. Retrieved 12 November 2016.

- "Past Awards". National Society of Film Critics. Retrieved 12 November 2016.

Bibliography

- Balio, Tino (1987). United Artists: The Company That Changed the Film Industry. Madison: University of Wisconsin Press. ISBN 9780299114404.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Bergom-Larsson, Maria (1978). Ingmar Bergman and Society. London: Tantivy Press.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Broman, Per F. (2008). "Music, Sound, and Silence in the Films of Ingmar Bergman". Mind the Screen: Media Concepts According to Thomas Elsaesser. Amsterdam: Amsterdam University Press. ISBN 9789089640253.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Cohen-Shalev, Amir (2002). Both Worlds at Once: Art in Old Age. Lanham: University Press of America. ISBN 9780761821878.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Gado, Frank (1986). The Passion of Ingmar Bergman. Durham: Duke University Press. ISBN 9780822305866.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Gervais, Marc (1999). Ingmar Bergman: Magician and Prophet. Montreal and Kingston: McGill-Queen's University Press. ISBN 9780773520042.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Kael, Pauline (2011). "A Sign of Life". The Age of Movies: Selected Writings of Pauline Kael. New York: Library of America. ISBN 9781598531718.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Laine, Tarja (2008). "Failed Tragedy and Traumatic Love in Ingmar Bergman's Shame". Mind the Screen: Media Concepts According to Thomas Elsaesser. Amsterdam: Amsterdam University Press. ISBN 9789089640253.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Macnab, Geoffrey (2009). Ingmar Bergman: The Life and Films of the Last Great European Director. London and New York: I.B. Tauris & Co. ISBN 9780857713575.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Marker, Lise-Lone; Marker, Frederick J. (1992). Ingmar Bergman: A Life in the Theater. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 9780521421218.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Steene, Birgitta (2005). Ingmar Bergman: A Reference Guide. Amsterdam: Amsterdam University Press. ISBN 9789053564066.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Vermilye, Jerry (2002). Ingmar Bergman: His Life and Films. Jefferson: McFarland & Company Publishers. ISBN 9780786411603.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Winter, Jessica; Hughes, Lloyd; Armstrong, Richard; Charity, Tom (2007). The Rough Guide to Film. Penguin Group. ISBN 9781405384988.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

External links

- Shame on IMDb

- Shame at the Swedish Film Institute Database

- Shame: Twilight of the Humans an essay by Michael Sragow at the Criterion Collection