Terms for Syriac Christians

Syriac Christians are an ethnoreligious grouping of various ethnic communities of indigenous Semitic and often Neo-Aramaic-speaking Christian people of Iraq, Syria, Iran, Turkey, Lebanon, Jordan, Palestine, and Israel. Syriac Christians advocate different terms for ethnic self-designation. Syriac Christians from the Middle East are theologically and culturally closely related to, but should not be confused with, the Saint Thomas Christians from India, whose ties to Syriac Christians were the result of trade links and migration by Assyrian Christians from Mesopotamia and the Middle East mostly around the 9th century.

Historically, the three ethnic names used for those who would become Syriac Christians were extant before the advent of Christianity: Assyrian, referring to the land and people of Assyria in northern Mesopotamia, Aramean, referring to the people of Aram in The Levant, and Syrian/Syriac, originally being used specifically as an Indo-European corruption of Assyrian, but from the late 4th century BC, being applied by the Seleucid Greeks to the Arameans of The Levant.

Other purely doctrinal and theological terms[1][2][3] such as Syriac Christian, Chaldean, Jacobite, and Nestorian, appeared much later, usually as labels imposed by theologians from Europe. The problem became more acute in 1946, when with the creation and independence of Syria, the adjective Syrian came to refer to that Arab-majority independent state, where Syriac Christians formed a minority.

List overview

A simplified list presents (self-)identifications of Syriac Christians with regard to: 1) ethnicity (which may or may not be ethno-religious and/or national/nationalistic); and 2) religious denomination:

- 1. Ethnic/ethno-religious identity:

- Aramean (mostly endorsed by some in the Syriac Orthodox Church)

- Assyrian (endorsed mostly by members of East Syriac denominations, but also by a minority in the Syriac Orthodox Church)

- Assyrian nationalism promoted by claims of Assyrian continuity

- Chaldean (once the generally accepted ethnic term, now endorsed by a minority in the Chaldean Catholic Church)

- Phoenicianism (endorsed by some in the Maronite Church around Lebanon)

- Syriac (mostly endorsed as a national identity by many in the Syriac Orthodox Church)

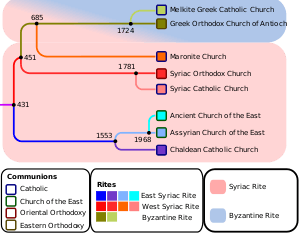

- 2. Christian denomination:

- Eastern Christian

- Syriac Christian

- West Syriac

- Maronite Church (410-/685-)

- Syriac Orthodox Church (518-)

- Syriac Catholic Church (1662-)

- East Syriac (legacy of the Church of the East, also called the "Nestorian Church", 5th century-1552)

- Chaldean Catholic Church (1552-)

- Assyrian Church of the East (1692-)

- Ancient Church of the East (1968-)

- Assyrian Evangelical Church (1870-)

- Assyrian Pentecostal Church (1940-)

- Saint Thomas Christians in India were originally associated with the Church of the East (1st century-), but some of them became part of the Syriac Orthodox Church (1665-), and today they are divided among various denominations and traditions

- West Syriac

- Syriac Christian

- Eastern Christian

A third identity concerns citizenship of and/or national identification with an existing sovereign state, such as being Syrian (Syrian Arab Republic), German (Germany), Swedish (Sweden), American (United States), etc. "Syrian" identity in particular may be confusing for an outsider, since someone may self-identify as both Syriac and Syrian: as a "Syrian Syriac Aramean" (a Syriac Christian from Syria who ethnically self-identifies as an Aramean) or a "Syrian-Swedish Assyrian Chaldean Catholic" (a Swede originating from Syria who ethnically identifies as an Assyrian - and may or may not promote Assyrian nationalism - and who belongs to the Chaldean Catholic Church), etc.

Historical background

Ancient history

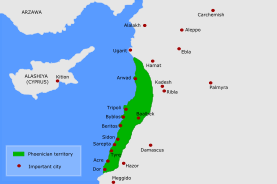

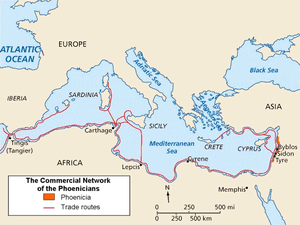

In the pre-Christian era, during the mid- and late Bronze Age and Iron Age, the northern part of Iraq and parts of south-east Turkey and north-east Syria were encompassed by Assyria from the 25th century BC, southern Iraq by Babylonia from the 19th century BC, the Mediterranean coast of Lebanon and Syria by Phoenicia from the 13th century BC, and the remainder of Syria together with parts of south-central Turkey, by Aramea, also from the 13th century BC.

Modern Israel, Jordan, the Palestinian Territories and the Sinai peninsula were encompassed by various Canaanite states from the 13th century BC, such as Israel, Judah, Samarra, Edom, Ammon, the Amalekites and Moab. The Arabs emerged in the Arabian Peninsula in the mid-9th century BC, and the long extinct Chaldeans migrated to south-east Iraq from The Levant at the same time.

This entire region (together with Arabia, Asia Minor, Persia, Egypt, the Caucasus, and parts of Ancient Iran/Persia and Ancient Greece) fell under the Neo-Assyrian Empire (935–605 BC), which introduced Imperial Aramaic as the lingua franca of its empire.

Little changed under the succeeding Achaemenid Empire (544–323 BC), which retained these lands as provinces under Achaemenid control, although some ethnicities and lands, such as Chaldea, Moab, Edom and Canaan disappeared before the Achaemenid period.

The terminological problem dates from the Seleucid Empire (323–150 BC), which applied the term Syria, the Greek and Indo-Anatolian form of the name Assyria, which had existed even during the Assyrian Empire, not only to the homeland of the Assyrians but also to lands to the west in the Levant, previously known as Aramea, Eber Nari and Phoenicia (modern Syria, Lebanon and northern Israel) that later became part of the empire. This caused not only the original Assyrians, but also the ethnically and geographically distinct Arameans and Phoenicians of the Levant to be collectively called Syrians and Syriacs in the Greco-Roman world.

Syriac Christianity was established from an early stage in Syriac or Aramaic-speaking areas both in the East (ruled in turn by the Parthians and the Persians) and in the Roman-ruled West. The Church of the East (the mother church of the modern Assyrian Church of the East, Chaldean Catholic Church and Ancient Church of the East) was founded as a distinct Church in 410, when, in the Council of Seleucia-Ctesiphon, Christianity within the Sasanid Empire was organized, after the model approved by the 325 First Council of Nicea, as six ecclesiastical provinces, and recognized the bishop of Seleucia-Ctesiphon, the imperial capital, as having ecclesiastical authority throughout the empire.[4][5][6] Aramea was also home to significant Christian communities in the Roman Empire, with Syrian Antioch being the center of some of the earliest Christian communities. The Syriac Orthodox Church and Maronite Church later emerged in this region as distinct from the Church recognized throughout that empire.

Until the 7th-century Arab Islamic conquests, Syriac Christianity was thus divided between two empires, Sassanid Persia in the east and Rome/Byzantium in the west. The western group in Syria (ancient Aramea), the eastern in Parthian, Persian and (for merely two years) Roman Assyria, east of the Tigris and so of Mesopotamia. Syriac Christianity was divided from the 5th century over questions of Christological dogma, viz. Nestorianism in the east and Monophysitism and Dyophysitism in the west.

Modern history

The controversy is not restricted to exonyms like English "Assyrian" vs. "Aramean", but also applies to self-designation in Neo-Aramaic, the "Aramean" faction from Turkey and Syria endorses both Sūryāyē (ܣܘܪܝܝܐ) and Ārāmayē (ܐܪܡܝܐ), while the "Assyrian" faction from Iraq, Iran, north east Syria and southeast Turkey insists on Āṯūrāyē (ܐܬܘܪܝܐ) but also accepts Sūryāyē (ܣܘܪܝܝܐ).

Assyria-Syria naming controversy

The question of ethnic identity and self-designation is sometimes connected to the scholarly debate on the etymology of "Syria". The question has a long history of academic controversy.[7]

The 21st century AD discovery of the Cinekoy Inscription appears to conclusively prove that the term Syria derives from the Assyrian term 𒀸𒋗𒁺 𐎹 Aššūrāyu., and referred to Assyria and Assyrian. The Çineköy inscription is a Hieroglyphic Luwian-Phoenician bilingual, uncovered from Çineköy, Adana Province, Turkey (ancient Cilicia), dating to the 8th century BC. Originally published by Tekoglu and Lemaire (2000),[8] it was more recently the subject of a 2006 paper published in the Journal of Near Eastern Studies, in which the author, Robert Rollinger, lends strong support to the age-old debate of the name "Syria" being derived from "Assyria" (see Etymology of Syria). The examined section of the Luwian inscription reads:

§VI And then, the/an Assyrian king (su+ra/i-wa/i-ni-sa(URBS)) and the whole Assyrian "House" (su+ra/i-wa/i-za-ha(URBS)) were made a fa[ther and a mo]ther for me,

§VII and Hiyawa and Assyria (su+ra/i-wa/i-ia-sa-ha(URBS)) were made a single “House.”

The corresponding Phoenician inscription reads:

And the king [of Aššur and (?)]

the whole “House” of Aššur (’ŠR) were for me a father [and a]

mother, and the DNNYM and the Assyrians (’ŠRYM)

The object on which the inscription is found is a monument belonging to Urikki, vassal king of Hiyawa (i.e. Cilicia), dating to the 8th century BC. In this monumental inscription, Urikki made reference to the relationship between his kingdom and his Assyrian overlords. The Luwian inscription reads "Sura/i" whereas the Phoenician translation reads ’ŠR or "Ashur" which, according to Rollinger (2006), "settles the problem once and for all".[9]

Some scholars in the past rejected the theory of 'Syrian' being derived from 'Assyrian' as "naive" and based purely on onomastic similarity in Indo-European languages,[10] until the inscription identified the origins of this derivation.[11]

In Classical Greek usage, Syria and Assyria were used almost interchangeably. Herodotus's distinctions between the two in the 5th century BC were a notable early exception,[12] Randolph Helm emphasizes that Herodotus "never" applied the term Syria to Mesopotamia, which he always called "Assyria", and used "Syria" to refer to inhabitants of the coastal Levant.[13] While himself maintaining a distinction, Herodotus also claimed that "those called Syrians by the Hellenes (Greeks) are called Assyrians by the barbarians (non-Greeks).[14][15]

In the first century prior to the dawn of Christianity, the geographer Strabo (64 BC–21 AD) writes that whom historians (most likely Greek ones) call Syrian were actually Assyrian;

When those who have written histories about the Syrian empire say that the Medes were overthrown by the Persians and the Syrians by the Medes, they mean by the Syrians no other people than those who built the royal palaces in Ninus (Nineveh); and of these Syrians, Ninus was the man who founded Ninus, in Aturia (Assyria) and his wife, Semiramis, was the woman who succeeded her husband... Now, the city of Ninus was wiped out immediately after the overthrow of the Syrians. It was much greater than Babylon, and was situated in the plain of Aturia. Although the mention of Ninus as having founded Assyria is inaccurate, as is the claim that Semiramis was his wife, the salient point in Strabo's statement is the recognition that the Greek term Syria historically meant Assyria. It was the Assyrian Empire, not the "Syrian Empire", that was overthrown by the Medes and built palaces in Ninevah.[16] However, while this statement provides insight into how "Syrian" was used by the Greeks (supporting the "lost a" theory), claims that Syria and Assyria were considered synonymous to non-Greeks, including Syrians themselves, as alleged by Herodotus, are cast in doubt considering his remark in Geographika: “Poseidonius (a celebrated polymath and native of Apamea, Syria) conjectures that the names of these nations also are akin; for, says he, the people whom we call Syrians are by the Syrians themselves called Arameans... for the people in Syria are Aramaeans”.

Flavius Josephus, Roman Jewish historian writing in the 1st century AD describes the inhabitants of the state of Osroene as Assyrians.[17] Osroene was a Syriac-speaking state based around Edessa in Upper Mesopotamia,[18] a key center of early Syriac Christianity. However, in Antiquities of the Jews, he writes that "Aram had the Arameans, which the Greeks called Syrians."[19]

Justinus, the Roman historian wrote in 300 AD: The Assyrians, who are afterwards called Syrians, held their empire thirteen hundred years.[20]

"Syria" and "Assyria" were not fully distinguished by Greeks until they became better acquainted with the Near East. Under Macedonian rule after Syria's conquest by Alexander the Great, "Syria" was restricted to the land west of the Euphrates. Likewise, the Romans clearly distinguished the Assyria and Syria.[21]

Unlike the Indo-European languages, the native Semitic name for Syria has always been distinct from Assyria. During the Akkadian Empire (2335–2154 BC), Neo-Sumerian Empire (2119–2004 BC) and Old Assyrian Empire (1975–1750 BC) the region which is now Syria was called The Land of the Amurru and Mitanni, referring to the Amorites and the Hurrians. Beginning from the Middle Assyrian Empire (1365–1020 BC), and also in the Neo Assyrian Empire (935–605 BC) and the succeeding Neo-Babylonian Empire (605–539 BC) and Achaemenid Empire (539–323 BC), Syria was known as Aramea and later Eber Nari. The term Syria emerged only during the 9th century BC, and was only used by Indo-Anatolian and Greek speakers, and solely in reference to Assyria.

According to Tsereteli, the Georgian equivalent of "Assyrians" appears in ancient Georgian, Armenian and Russian documents,[22] making the argument that the nations and peoples to the east and north of Mesopotamia knew the group as Assyrians, while to the West, beginning with Luwian, Hurrian and later Greek influence, the Assyrians were known as Syrians.[9]

Historic names of the Syriac Christians

Historically, the Syriac Christians have been referred to as "Syrian", "Aramean", "Chaldean", and "Assyrian".[23]

Purely theological terms such as Nestorian, Jacobite and Chaldean Catholic referred only to specific groups. Nestorian emerged after the Nestorian Schism that followed the First Council of Ephesus in 431 AD, Jacobite after the Council of Chalcedon in 451 AD, and Chaldean Catholic only in the late 18th century AD, subsequent to groups in northern Iraq breaking from the Church of the East. These three terms are solely denominational, and not ethnic in any sense, and were applied to Syriac Christians by Europeans.

The historical English term for the group is "Syrians" (as in, e.g., Ephraim the Syrian). It is still in use, not only in India, where it is applied especially to the various groups of Saint Thomas Christians, but also generally,[24][25] although, after the 1936 declaration of the Syrian Arab Republic, the term "Syrian" has come also to designate citizens of that state regardless of ethnicity, with Syriac-Arameans and Assyrians only being indigenous ethnic minorities within that nation. The designation "Assyrians" has also become current in English besides the traditional "Syrians" since the late 19th century and particularly after the Assyrian genocide and the resulting Assyrian independence movement.[23]

Ethnic name dispute

The adjective "Syriac" properly refers to the Syriac language (founded in 5th century BC Assyria) exclusively and is not a demonym. The OED explicitly still recognizes this usage alone:

- "A. adj. Of or pertaining to Syria: only of or in reference to the language; written in Syriac; writing, or versed, in Syriac."

- "B. n. The ancient Semitic language of Mesopotamia and Syria; formerly in wide use (="Aramaic"; now, the form of Aramaic used by Syrian Christians, in which the Peshitta version of the Bible is written."[26]

Etymologically, it is generally accepted that the term Syrian (and thus derivatives such as Syriac) derive from Assyrian. The 21st-century discovery of the Çineköy Inscription appears to conclusively prove the already largely prevailing position that the term "Syria" derives from the Assyrian term Aššūrāyu. (see Etymology of Syria).

The noun "Syriac" (plural "Syriacs") has nevertheless come into common use as a demonym following the declaration of the Syrian Arab Republic to avoid the ambiguity of "Syrians". Limited de facto use of "Syriacs" in the sense of "authors writing in the Syriac language" in the context of patristics can be found even before World War I.[27] Many modern scholars similarly use "Aramaic" a linguistic term without prejudicing particular identities.

Since the 1980s, a dispute between, on the one hand, the East Aramaic speaking Assyrians (aka Chaldo-Assyrians, who are indigenous Christians from northern Iraq, northwestern Iran, southeastern Turkey, northeastern Syria and the Caucasus, and derive their national identity from the Bronze and Iron Age Assyria. On the other hand, the now largely Arabic-speaking, but previously West Aramaic speaking Arameans, who are mainly from central, south, west and northwestern Syria, south-central Turkey, and Israel, emphasizing their descent from the Levantine Arameans instead) has become ever more pronounced. In the light of this dispute, the traditional English designation "Assyrians" has come to appear taking an Assyrianist position, for which reason some official sources in the 2000s have come to use emphatically neutral terminology, such as "Assyrian/Chaldean/Syriac" in the US census, and "Assyrier/Syrianer" in the Swedish census.

Another distinction can be made: unlike the Assyrians, who emphasize their non-Arab ethnicity and have historically sought a state of their own, some urban Chaldean Catholics are more likely to assimilate into Arab identity.[28] Other Chaldeans, particularly in America, identify with the ancient Chaldeans of Chaldea rather than the Assyrians. In addition, while Assyrians self-define as a strictly Christian nation, Aramaic organizations generally accept that Islamic Arameans exist and that many Muslims in historic Aramea were converts (forced or voluntary) from Christianity to Islam.[29] An exception to the near-extinction of Western Aramaic are the Lebanese Maronite speakers of Western Neo-Aramaic, however, they largely identify with the Phoenicians (the ancient people of Lebanon) and not Arameans. Some Muslim Lebanese nationalists espouse Phoenician identity as well.

In the Aramaic language, both terms are used: Sūrāyē/Sūryāyē ("Syrian") or Āṯūrāyē ("Assyrian") (in the Western dialect the vowel ā is pronunced o).[30]

Names in diaspora

United States

During the 2000 United States census, Syriac Orthodox Archbishops Cyril Aphrem Karim and Clemis Eugene Kaplan issued a declaration that their preferred English designation is "Syriacs".[31] The official census avoids the question by listing the group as "Assyrian/Chaldean/Syriac".[32][33] Some Maronite Christians also joined this US census (as opposed to Lebanese American).[34]

Sweden

In Sweden, this name dispute has its beginning when immigrants from Turkey, belonging to the Syriac Orthodox Church emigrated to Sweden during the 1960s and were applied with the ethnic designation Assyrians by the Swedish authorities. This caused many from outside Iraq who preferred the indigenous designation Suryoyo (who today go by the name Syrianer) to protest, which led to the Swedish authorities began using the double term assyrier/syrianer.[35][36]

National identities

Assyrian identity

.jpg)

An Assyrian identity is today maintained by followers of the Assyrian Church of the East, the Ancient Church of the East, the Chaldean Catholic Church, Assyrian Pentecostal Church, Assyrian Evangelical Church, and Eastern Aramaic speaking communities of the Syriac Orthodox Church (particularly in northern Iraq, north eastern Syria and south eastern Turkey) and to a much lesser degree the Syriac Catholic Church.[38] Those identifying with Assyria, and with Mesopotamia in general, tend to be Mesopotamian Eastern Aramaic speaking Christians from northern Iraq, north eastern Syria, south eastern Turkey and north west Iran, together with communities that spread from these regions to neighbouring lands such as Armenia, Georgia, southern Russia, Azerbaijan and the Western World.

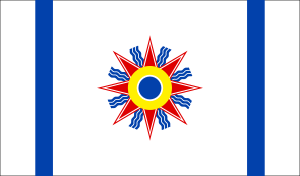

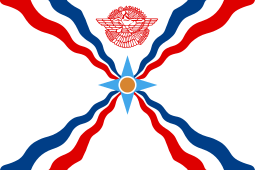

The Assyrianist movement originated in the 19th to early 20th centuries, in direct opposition to Pan-Arabism and in the context of Assyrian irredentism. It was exacerbated by the Assyrian Genocide and Assyrian War of Independence of World War I. The emphasis of Assyrian antiquity grew ever more pronounced in the decades following World War II, with an official Assyrian calendar introduced in the 1950s, taking as its era the year 4750 BC, the purported date of foundation of the city of Assur and the introduction of a new Assyrian flag in 1968. Assyrians tend to be from Iraq, Iran, southeast Turkey, northeast Syria, Armenia, Georgia, southern Russia and Azerbaijan, as well as in diaspora communities in the US, Canada, Australia, Great Britain, Sweden, Netherlands etc.

Assyrian continuity, the idea that the modern Christians of Mesopotamia are descended from the Ancient Assyrians, is supported by Assyriologists H.W.F. Saggs,[39] Robert D. Biggs,[40] and Simo Parpola,[41] Tom Holland and Iranologist Richard Nelson Frye.[7][42] It is denied by historian John Joseph, himself a modern Assyrian,[43][44] and Semitologist Aaron Michael Butts,[45]

Eastern Syriac Christians are on record, but only from the late nineteenth century, calling themselves Aturaye, Assyrians,[46] and the region now in Iraq, northeast Syria and southeast Turkey was still known as Assyria (Athura, Assuristan) until the 7th century AD.

Writing in 1844, the year following the first press reports of the magnificent Assyrian palace reliefs discovered by Paul-Émile Botta and Austen Henry Layard, the first inklings of which had been made known to the West by Claudius Rich in 1836, Horatio Southgate commented that in 1841 he had found that Armenians referred to those whom he called "the Syrians" (the West Syriacs of the Syriac Orthodox Church, as distinct from the East Syriacs of the Church of the East, whom he called "Nestorians" or "Chaldeans", as distinct from those he called "Papal Chaldeans")[47] as Assouri, a name that Southgate associated with the ancient Assyrians: "I began to make inquiries for the Syrians. The people informed me that there were about one hundred families of them in the town of Kharpout, and a village inhabited by them on the plain. I observed that the Armenians did not know them under the name which I used, Syriani; but called them Assouri, which struck me the more at the moment from its resemblance to our English name Assyrians, from whom they claim their origin, being sons, as they say, of Assour, (Asshur,) who 'out of the land of Shinar went forth, and builded Nineveh, and the city Rehoboth, and Calah, and Resin between Nineveh and Calah: the same is a great city'."[48] In reality, Assouri means simply Syrian, the Armenian word for "Assyrian" is Asorestants’i.[21] This shows that in the mid-nineteenth century Jacobite Syrian Christians, while not self-identifying as Assyrians, considered themselves of Assyrian descent, although systematic use of "Assyrians" to mean Syriac Christians appears for the first time in the context of an effort by the Archbishop of Canterbury's Mission to the Assyrian Christians to avoid using the term "Nestorian" for the members of the Church of the East not in communion with Rome.[49]

Southgate indicates elsewhere that, while he calls the West Syrian churches "Jacobite" and "Syrian Catholic" and uses the national term "Syrian" for both conjointly, the East Syrians are "Chaldeans" (their traditional national term) or "Nestorians". The Chaldeans, he says, consider that they themselves are descended from the Assyrians and that the Jacobites are descended "from the Syrians, whose chief city was Damascus".[50]

Syriac identity

The term Syriac was historically taken mainly as a linguistic (Syriac language) and liturgical (Syriac rite) term, referring to Neo-Aramaic-speaking Christians from the Near East in general. In an ethnic sense, Syriac Christians identified as Assyrian, Aramean, or Syrian, but in light of the use of the term Syrian as a demonym for residents of the Syrian Arab Republic, some Syriac Christians have also advocated the term Syriac as an ethnic identifier, particularly members of the Syriac Orthodox Church, the Syriac Catholic Church' and to a much lesser degree, the Maronite Church, in a way of preserving their historic endonym while distinguishing themselves from Arab Syrians. Those self-identifying as Syriacs tend to be from western, northwestern, southern, and central Syria, as well as south-central Turkey.

In 2000, the Holy Synod of the Syriac Orthodox Church ruled that in English this church should be called "Syriac" after its official liturgical Syriac language (i.e. Syriac Orthodox Church).[51]

Organisations such as the Syriac Union Party in Lebanon and Syriac Union Party in Syria, as well as the European Syriac Union, espouse a Syriac identity. Syriac identity has become closely merged with the Aramean identity in some quarters, whilst being accepted by Assyrians also, due to the etymological origin of the term.

Chaldean and Assyro-Chaldean identity

What is now referred to as Biblical Aramaic was until recently called Chaldaic or Chaldee,[52][53] and East Syrian Christians, whose liturgical language was and is a form of Aramaic, were called Chaldeans,[54] as an ethnic, not a religious term. Hormuzd Rassam applied the term "Chaldeans" to the "Nestorians", those not in communion with Rome, no less than to the Catholics.[55] He stated that "the present Chaldeans, with a few exceptions, speak the same dialect used in the Targum, and in some parts of Ezra and Daniel, which are called 'Chaldee'."[56][57]

Until at least the mid-nineteenth century, the name "Chaldean" was the ethnic name for all the area's Christians, whether in or out of communion with Rome. William Francis Ainsworth, whose visit was in 1840, spoke of the non-Catholics as "Chaldeans" and of the Catholics as "Roman-Catholic Chaldeans".[58] For those Chaldeans "who retained their ancient faith", Ainsworth said, the name "Nestorian" was invented in 1681 to distinguish them from those in communion with Rome.[59] A little later, Austen Henry Layard also used the term "Chaldean" even for those he also called Nestorians.[60] The same term had earlier been used by Richard Simon in the seventeenth century, writing: "Among the several Christian sects in the Middle East that are called Chaldeans or Syrians, the most sizeable is that of the Nestorians".[61] As indicated above, Horatio Southgate, who said that the members of the Syriac Orthodox Church (West Syrians) considered themselves descendants of Asshur, the second son of Shem, called the members of the divided Church of the East Chaldeans and Papal Chaldeans.

"Chaldean" was the term used, much earlier, to speak of the Christians from northern Mesopotamia who entered an ephemeral union with the Catholic Church in Cyprus in the 15th century, and those who in their ancestral towns entered into communion with the Catholic Church between the 16th and 18th centuries.[62][63][64][65]

Although it was only towards the end of the 19th century that the term "Assyrian" became accepted, largely through the influence of the Archbishop of Canterbury's Mission to the Assyrian Christians, at first as a replacement for the term "Nestorian", but later as an ethnic description,[49] today even members of the Chaldean Catholic Church, such as Raphael Bidawid, patriarch of the Chaldean Catholic Church from 1989 to 2003, accept "Assyrian" as an indication of nationality, while "Chaldean" has for them become instead an indication of religious confession. He stated: "When a portion of the Church of the East became Catholic in the 17th Century, the name given was ‘Chaldean’ based on the Magi kings who were believed by some to have come from what once had been the land of the Chaldean, to Bethlehem. The name ‘Chaldean’ does not represent an ethnicity, just a church... We have to separate what is ethnicity and what is religion... I myself, my sect is Chaldean, but ethnically, I am Assyrian."[66] Before becoming patriarch, he said in an interview with the Assyrian Star newspaper: "Before I became a priest I was an Assyrian, before I became a bishop I was an Assyrian, I am an Assyrian today, tomorrow, forever, and I am proud of it."[67]

That was a sea change from the earlier situation, when "Chaldean" was a self-description by prelates not in communion with Rome: "Nestorian patriarchs occasionally used 'Chaldean' in formal documents, claiming to be the 'real Patriarchs' of the whole 'Chaldean Church'."[68]

"Assyro-Chaldeans", a combination of the newer term "Assyrian" and the older "Chaldean", was used in the Treaty of Sèvres, which spoke of "full safeguards for the protection of the Assyro-Chaldeans and other racial or religious minorities".[69]

Hannibal Travis states that, in recent times, a small and mainly United States-based minority within the Chaldean Catholic Church have begun to espouse a separate Chaldean ethnic identity.[70]

In 1875 Henry John Van-Lennep wrote about Assyrians that belonged to the Chaldean Church, which was, according to him a generic name.[71] Van-Leppen stated that: "At the schism on account of Nestorius, the Assyrians, under the generic name of the Chaldean Church, mostly separated from the orthodox Greeks, and, being under the rule of the Persians, were protected against persecution."[71]

Aramean identity

Advocated by a number of Syriac Christians most notably members of the Syriac Orthodox Church and Syriac Catholic Church, modern Arameans claim to be the descendants of the ancient Arameans who emerged in the Levant during the Late Bronze Age, who following the Bronze Age collapse formed a number of small ancient Aramean kingdoms before they were conquered by the Neo-Assyrian Empire in the course of the 10th to late 7th centuries BC. They have maintained linguistic, Aramean and cultural independence despite centuries of Arabization, Islamization as well as Turkification, although Levantine Western Aramaic now has very few native speakers. They were among the first peoples to embrace Christianity during the 1st and 2nd centuries AD. During Horatio Southgate's travels through Mesopotamia, he encountered indigenous Christians and stated that the Jacobites in the region of Levant called themselves for Syrians "whose chief city was Damascus".[72]

Such an Aramean identity is mainly held by a number of Syriac Christians in southcentral Turkey, southeastern Turkey, western, central, northern and southern Syria and in the Aramean diaspora especially in Germany and Sweden.[73] In English, they self-identify as "Syriac", sometimes expanded to "Syriac-Aramean" or "Aramean-Syriac". In Swedish, they call themselves Syrianer, and in German, Aramäer is a common self-designation.

The Aramean Democratic Organization, based in Lebanon, is an advocate of the Aramean identity and an independent state in their ancient homeland of Aram.

Self-identification of some Syriac Christians with Arameans is well documented in Syriac literature. Mentions by notable individuals include that of the poet-theologian Jacob of Serugh, (c. 451 – 29 November 521) who describes Venerated Father St. Ephrem the Syrian (c. 306 – 373) as "He who became a crown for the people of the Aramaeans [armāyūthā], (and) by him we have been brought close to spiritual beauty".[74] Ephrem himself made references to Aramean origins,[75] calling his country Aram-Nahrin and his language Aramaic, and describing Bar-Daisan (d. 222) of Edessa as "The Philosopher of the Arameans", who "made himself a laughing-stock among Arameans and Greeks.” Michael the Elder (d. 1199) writes of his race as that of "the Aramaeans, namely the descendants of Aram, who were called Syrians.”[76] Bar Hebraeus (d. 1286) writes in his Book of Rays of the "Aramean-Syrian nation".

However, references such as these to an Aramean identity are scarce after the early Middle Ages, until the development of Aramean nationalism in the late 20th century.

In 2014, Israel has decided to recognize the Aramean community within its borders as a national minority, allowing most of the Syriac Christians in Israel (around 10,000) to be registered as "Aramean" instead of "Arab".[77] This decision on part of the Israeli Interior Ministry highlights the growing awareness regarding the distinctness of the Aramean identity as well as their plight due to the historical Arabization of the region.

Phoenician identity

Most of the Maronites identify with a Phoenician origin, as do much of the Lebanese population, and do not see themselves as Assyrian, Syriac or Aramean. This comes from the fact that present day Lebanon, the Mediterranean coast of Syria, and northern Israel is the area that roughly corresponds to ancient Phoenicia and as a result like the majority of the Lebanese people identify with the ancient Phoenician population of that region.[78] Moreover, the cultural and linguistic heritage of the Lebanese people is a blend of both indigenous Phoenician elements and the foreign cultures that have come to rule the land and its people over the course of thousands of years. In a 2013 interview the lead investigator, Pierre Zalloua, pointed out that genetic variation preceded religious variation and divisions:"Lebanon already had well-differentiated communities with their own genetic peculiarities, but not significant differences, and religions came as layers of paint on top. There is no distinct pattern that shows that one community carries significantly more Phoenician than another."[79]

However, a small minority of Lebanese Maronites like the Lebanese author Walid Phares tend to see themselves to be ethnic Assyrians and not ethnic Phoenicians. Walid Phares, speaking at the 70th Assyrian Convention, on the topic of Assyrians in post-Saddam Iraq, began his talk by asking why he as a Lebanese Maronite ought to be speaking on the political future of Assyrians in Iraq, answering his own question with "because we are one people. We believe we are the Western Assyrians and you are the Eastern Assyrians."[80]

Another small minority of Lebanese Maronites like the Maronites in Israel tend to see themselves to be ethnic Arameans and not ethnic Phoenicians.[77]

However, other Maronite factions in Lebanon, such as Guardians of the Cedars, in their opposition to Arab nationalism, advocate the idea of a pure Phoenician racial heritage (see Phoenicianism). They point out that all Lebanese people are of pre-Arab and pre-Islamic origin, and as such are at least, in part, of the Phoenician-Canaanite stock.[78]

Saint Thomas Christians of Kerala, India

The Saint Thomas Christians of India, where they are known as Syrian Christians, though ethnically unrelated to the peoples known as Assyrian, Aramean or Syrian/Syriac, had strong cultural and religious links with Mesopotamia as a result of trade links and missionary activity by the Church of the East at the height of its influence. Following the 1653 Coonan Cross Oath, many Saint Thomas Christians passed to the Syriac Orthodox Church and later split into several distinct churches. The majority, remaining faithful to the East Syriac Rite, form the Syro-Malabar Catholic Church, from which a small group, known as the Chaldean Syrian Church, seceded and in the early 20th century linked with what is now called the Assyrian Church of the East.

Syrian identity

"Syrian" is a national identity for a citizen of the Syrian Arab Republic, whether Christian or not.

In India, "Syrian Christians", also known as Saint Thomas Christians, "are a distinct, endomagous ethnic group, in many ways similar to a caste. They have a history of close to two thousand years, and in language, religion, and ethnicity, they are related to Persian as well as West Syrian Christian traditions".[81]

Outside of India, Syrian Christians are all those Christians whose liturgies are in the Syriac language, even if they have been Arabized[82] or live in other continents. A distinction is made between East and West Syrians in accordance with their use of the East Syriac Rite or the West Syriac Rite.[83][84][85]

Although inclusive of both Western and Eastern Syrian Christians, the term "Syrian Christians" is sometimes used in contexts where it refers more specifically to the Church of the East.[86][87]

Other names

Members of the Church of the East have been called Nestorians, since their church does not use "Mother of God" as a description of Mary, mother of Jesus, choosing instead to call her "Mother of Christ",[88] and has therefore been accused of the Christological doctrine known as Nestorianism, which emphasizes the distinction between Christ's humanity and divinity to such an extent that its critics say it makes of him two distinct individuals. The justice of imputing this heresy to Nestorius, Patriarch of Constantinople from 428 to 431, whom the Assyrian Church of the East venerates as a saint, is disputed.[89][90] David Wilmshurst states that for centuries "the word 'Nestorian' was used both as a term of abuse by those who disapproved of the traditional East Syrian theology, as a term of pride by many of its defenders [...] and as a neutral and convenient descriptive term by others. Nowadays it is generally felt that the term carries a stigma".[91] Sebastian P. Brock says: "The association between the Church of the East and Nestorius is of a very tenuous nature, and to continue to call that Church 'Nestorian' is, from a historical point of view, totally misleading and incorrect – quite apart from being highly offensive and a breach of ecumenical good manners."[92]

Apart from its religious meaning, the word "Nestorian" has also been used in an ethnic sense, as shown by the phrase "Catholic Nestorians".[93][94][95]

Members of the Syriac Orthodox Church are sometimes called Jacobites, after Jacob Baradaeus, an appellation that leaders of that church have both deplored[96] and accepted.[97] They are sometimes also called Monophysites, a term they have always disputed, preferring to be referred to as Miaphysites.[98]

In Western media, Syriac Christians are often spoken of simply as Christians of their country or geographical region of residence: "Iraqi Christians", "Iranian Christians", "Syrian Christians", and "Turkish Christians". The Assyrian International News Agency interpreted this as "Arabist policy of denying Assyrian identity and claiming that Assyrians, including Chaldeans and Syriacs, are Arab Christian minorities".[99] John Joseph states that, in Anglican writing, "'Assyrian Christians', which originally had only meant 'The Christians of geographical Assyria', soon became 'Christian Assyrians'",[100] and cites J. F. Coakley, who remarked that, in the same context, "the link created between the modern 'Assyrians' and the ancient Assyrians of Nineveh known to readers of the Old Testament [...] has proved irresistible to the imagination".[101]

They are also spoken of as Arab Christians. This too the Assyrian International News Agency interpreted as "Arabist policy" and mentioned in particular the dedication by the American-Arab Anti-Discrimination Committee of a webpage to the Maronite Kahlil Gibran, who is "viewed in Arabic literature as an innovator, not dissimilar to someone like W. B. Yeats in the West".[102] The vast majority of the Christians living in Israel self-identify as Arabs, but the Aramean community have wished to be recognized as a separate minority, neither Arab nor Palestinian but Aramean, while many others wish to be called Palestinian citizens of Israel rather than Arabs.[103] The wish of the Aramean community in Israel was granted in September 2014, opening for some 200 families the possibility, if they can speak Aramaic, to register as Arameans.[104] Other Christians in Israel criticized this move, seeing it as intended to divide the Christians and also to limit to Muslims the definition of "Arab".[105]

See also

- Assyrians

- Assyrian continuity

- Assyria

- Aram Nahrin

- Arameans

- Assyrian homeland

- Assyrianism

- Beth Nahrin

- Çineköy inscription

- Syria (etymology)

- Chaldea

- Babylonia

- Phoenicianism

- Aramea

- Arameanism

- Mesopotamia

- Neo-Aramaic

- The Hidden Pearl

References

Footnotes

- Travis, Hannibal. Genocide in the Middle East: The Ottoman Empire, Iraq, and Sudan. Durham, NC: Carolina Academic Press, 2010, 2007, pp. 237-77, 293–294

- http://conference.osu.eu/globalization/publ/08-bohac.pdf

- Nisan, M. 2002. Minorities in the Middle East: A History of Struggle for Self Expression. Jefferson: McFarland & Company.

- Wilhel Baum and Dietmar W. Winkler, The Church of the East: A Concise History (Routledge 2003), pp. 15-16

- Jean-Baptiste Chabot, Synodicon orientale ou Recueil de synodes nestoriens (Paris 1902), pp. 271-273

- T.J. Lamy, "Le concile tenu à Séleucie-Ctésiphon en 410" in Compte rendu du troisième Congrès scientifique international des catholiques tenu à Bruxelles du 5 au huit septembre 1894. Deuxième section : Sciences religeuses (Brussels 1895), pp. 250-276

- Frye, R. N. (October 1992). "Assyria and Syria: Synonyms" (PDF). Journal of Near Eastern Studies. 51 (4): 281–285. doi:10.1086/373570. Archived from the original (PDF) on 31 July 2004.

- Tekoglu, R. & Lemaire, A. (2000). La bilingue royale louvito-phénicienne de Çineköy. Comptes rendus de l’Académie des inscriptions, et belleslettres, année 2000, 960–1006.

- Rollinger, Robert (2006). "The terms "Assyria" and "Syria" again" (PDF). Assyriology. Journal of Near Eastern Studies. 65 (4): 284–287. doi:10.1086/511103.

- Festschrift Philologica Constantino Tsereteli Dicta, ed. Silvio Zaorani (Turin, 1993), pp. 106–107

- Rollinger, Robert (2006). "The terms "Assyria" and "Syria" again" (PDF). Journal of Near Eastern Studies 65 (4): 284–287. doi:10.1086/511103.

- The legacy of Mesopotamia, Stephanie Dalley, p94

- John Joseph (2000). The Modern Assyrians of the Middle East: A History of Their Encounter with Western Christian Missions, Archaeologists, and Colonial Powers. p. 21. ISBN 978-9004116412.

- (Pipes 1992), s:History of Herodotus/Book 7

Herodotus. "Herodotus VII.63".VII.63: The Assyrians went to war with helmets upon their heads made of brass, and plaited in a strange fashion which is not easy to describe. They carried shields, lances, and daggers very like the Egyptian; but in addition they had wooden clubs knotted with iron, and linen corselets. This people, whom the Hellenes call Syrians, are called Assyrians by the barbarians. The Chaldeans served in their ranks, and they had for commander Otaspes, the son of Artachaeus.

Herodotus. "Herodotus VII.72".VII.72: In the same fashion were equipped the Ligyans, the Matienians, the Mariandynians, and the Syrians (or Cappadocians, as they are called by the Persians).

Missing or empty|url=(help) - http://www.aina.org/articles/frye.pdf

- P. 195 (16. I. 2-3) of Strabo, translated by Horace Jones (1917), The Geography of Strabo London : W. Heinemann ; New York : G.P. Putnam's Sons

- https://books.google.com/books?id=Ta08AAAAIAAJ&printsec=frontcover&source=gbs_ge_summary_r&cad=0#v=onepage&q&f=false%5B%5D

- The Ancient Name of Edessa," Amir Harrak, Journal of Near Eastern Studies, Vol. 51, No. 3 (July 1992): 209-214 [3]

- Antiquities of the Jews, translated by William Whiston

- The Origins of Syrian Nationhood: Histories, Pioneers and Identity Adel Beshara

- Joseph, Assyria and Syria: Synonyms?, p. 38

- Tsereteli, Sovremennyj assirijskij jazyk, Moscow: Nauka, 1964.

- >John Joseph, The Modern Assyrians of the Middle East (BRILL 2000), pp. 1−32

- Mark A. Lamport (editor), Encyclopedia of Christianity in the Global South (Rowman & Littlefield 2018), volume 2, p. 906

- John Anthony McGuckin (editor), The Encyclopedia of Eastern Orthodox Christianity (John Wiley & Sons 2010)

- OED, online edition s.v. "Syriac". Retrieved November 2008

- e.g. "the later Syriacs agree with the majority of the Greeks" American Journal of Philology, Johns Hopkins University Press (1912), p. 32.

- "Chaldeans". Minority Rights Group.

- "ARAMAIC HISTORY". aramaic-dem.org.

- Nicholas Awde; Nineb Lamassu; Nicholas Al-Jeloo (2007). Aramaic (Assyrian/Syriac) Dictionary & Phrasebook: Swadaya-English, Turoyo-English, English-Swadaya-Turoyo. Hippocrene Books. p. 4. ISBN 978-0-7818-1087-6.

- Assyrian Heritage of the Christians of Mesopotamia Archived 26 November 2011 at the Wayback Machine

- Census 2000 Archived 5 July 2008 at the Wayback Machine

- "Syriac Orthodox Church Census 2000 Explanation in English". www.bethsuryoyo.com.

- "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 11 May 2003. Retrieved 11 May 2003.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- Assyriska Hammorabi Föreningen, Namnkonflikten Archived 20 February 2008 at the Wayback Machine

- Berntsson, p. 51

- Assyria Archived 12 October 2008 at the Wayback Machine

- From a lecture by J. A. Brinkman: "There is no reason to believe that there would be no racial or cultural continuity in Assyria, since there is no evidence that the population of Assyria was removed." Quoted in Efram Yildiz's "The Assyrians" Journal of Assyrian Academic Studies, 13.1, pp. 22, ref 24

- Saggs, The Might That Was Assyria, p. 290, “The destruction of the Assyrian empire did not wipe out its population. They were predominantly peasant farmers, and since Assyria contains some of the best wheat land in the Near East, descendants of the Assyrian peasants would, as opportunity permitted, build new villages over the old cities and carry on with agricultural life, remembering traditions of the former cities. After seven or eight centuries and various vicissitudes, these people became Christians.”

- Biggs, Robert (2005). "My Career in Assyriology and Near Eastern Archaeology" (PDF). Journal of Assyrian Academic Studies. 19 (1): 10. Archived from the original (PDF) on 27 February 2008.

Especially in view of the very early establishment of Christianity in Assyria and its continuity to the present and the continuity of the population, I think there is every likelihood that ancient Assyrians are among the ancestors of modern Assyrians of the area.

- Parpola, National and Ethnic Identity in the Neo-Assyrian Empire and Assyrian Identity in Post-Empire Times, p. 22

- Frye, Richard N. (1992). "Assyria and Syria: Synonyms". PhD., Harvard University. Journal of Near Eastern Studies.

The ancient Greek historian, Herodotus, wrote that the Greeks called the Assyrians, by the name Syrian, dropping the A. And that's the first instance we know of, of the distinction in the name, of the same people. Then the Romans, when they conquered the western part of the former Assyrian Empire, they gave the name Syria, to the province, they created, which is today Damascus and Aleppo. So, that is the distinction between Syria, and Assyria. They are the same people, of course. And the ancient Assyrian empire, was the first real, empire in history. What do I mean, it had many different peoples included in the empire, all speaking Aramaic, and becoming what may be called, "Assyrian citizens." That was the first time in history, that we have this. For example, Elamite musicians, were brought to Nineveh, and they were 'made Assyrians' which means, that Assyria, was more than a small country, it was the empire, the whole Fertile Crescent.

- John Joseph, "Assyria and Syria: Synonyms?"

- John Joseph, The Modern Assyrians of the Middle East, pp. 18−19

- Aaron Michael Butts, "Assyrian Christians" in Eckart Frahm (editor), A Companion to Assyria (John Wiley & Sons 2017), pp. 599−612

- John Joseph, The Modern Assyrians of the Middle East: A History of Their Encounter with Western Christian Missions, Archaeologists, and Colonial Powers, pp. 18 and 38

- Horatio Southgate, Narrative of a Visit to the Syrian [Jacobite] Church of Mesopotamia (Appleton 1844), p. 141

- Horatio Southgate, Narrative of a Visit to the Syrian [Jacobite] Church of Mesopotamia (Appleton 1844), p. 80. The quotation is 10:11-12's description of Asshur, the second son of Shem.

- Eckart Frahm, A Companion to Assyria (John Wiley & Sons 2017), p. 602

- Horatio Southgate, Narrative of a Tour Through Armenia, Kurdistan, Persia and Mesopotamia (Tilt and Roger 1840), pp. 179−180

- "SOCNews - The Holy Synod approves the name "Syriac Orthodox Church"". sor.cua.edu.

- William Gesenius, German original. "Gesenius Hebrew Chaldee Lexicon Old Testament Scriptures.Tregelles.1857. 24 files" – via Internet Archive.

- Gesenius, Wilhelm (16 January 2019). "Lexicon manuale hebraicum et chaldaicum in Veteris Testamenti libros: Post editionem germanicam tertiam latine elaboravit multisque modis retractavit et auxit Guil. Gesenius". Sumtibus Fr. Chr. Guil. Vogelii – via Google Books.

- Kristian Girling, The Chaldean Catholic Church: Modern History, Ecclesiology and Church-State Relations (Routledge 2017)

- "Even at the present time the Nestorians are considered a very warlike people, and the Armenians just the opposite, as they were in the time of Xenophon. Why then should the Armenians be called Armenians, but the Chaldeans merely Nestorians?" (Hormuzd Rassam, "Biblical Nationalities Past and Present" in Transactions of the Society of Biblical Archaeology, vol. VIII, part 1, p. 377)

- Hormuzd Rassam, "Biblical Nationalities Past and Present" in Transactions of the Society of Biblical Archaeology, vol. VIII, part 1, p. 378

- Ur of the Chaldees, from which Abraham originated, is placed by some scholars in northern Mesopotamia (Victor P. Hamilton, The Book of Genesis, Chapters 1-17 (Eerdmans 1990); Cyrus H. Gordon, "Where Is Abraham's Ur?" in Biblical Archaeology Review 3:2 (June 1977), pp. 20ff; Horatio Balch Hackett, A Commentary on the Original Text of the Acts of the Apostles (Boston 1852), p. 100).

- William Ainsworth, "An Account of a Visit to the Chaldeans ..." in The Journal of the Royal Geographical Society of London, Vol. 11 (1841), e.g., p. 36

- William F. Ainsworth, Travels and Researches in Asia Minor, Mesopotamia, Chaldea and Armenia (London 1842), vol. II, p. 272, cited in John Joseph, The Modern Assyrians of the Middle East (BRILL 2000), pp. 2 and 4

- Austen Henry Layard, Nineveh and its Remains (Murray 1850), p. 260

- Richard Simon, Histoire critique de la creance et des coûtumes des nations du Levant (Francfort 1684), p. 83

- Council of Florence, Bull of union with the Chaldeans and the Maronites of Cyprus Session 14, 7 August 1445 [1]

- Rabban, "Chaldean Catholic Church (Eastern Catholic)" in New Catholic Encyclopedia (2003); cf. McCarron, "Chaldean Rite" in New Catholic Encyclopedia (2003)

- Georges Roux, Ancient Iraq, 3rd ed., Penguin Books, London, 1991, p.381-382

- Joan Oates, Babylon, revised ed., Thames & Hudson, 1986

- Parpola, Simo (2004). "National and Ethnic Identity in the Neo-Assyrian Empire and Assyrian Identity in Post-Empire Times" (PDF). Journal of Assyrian Academic Studies. JAAS. 18 (2): 22. Archived from the original (PDF) on 17 July 2011.

- Mar Raphael J Bidawid in The Assyrian Star. September–October, 1974:5.

- John Joseph, The Modern Assyrians of the Middle East (BRILL 2000), p. 8

- "Section I, Articles 1 - 260 - World War I Document Archive". wwi.lib.byu.edu.

- Travis, Hannibal. Genocide in the Middle East: The Ottoman Empire, Iraq, and Sudan. Durham, NC: Carolina Academic Press, 2010, 2007, pp. 237-77, 293–294 ISBN 9781594604362

- Van-Lennep, Henry John, 1815-1889. (2000). Bible lands : their modern customs and manners illustrative of Scripture. Making of America. OCLC 612111329.CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)

- Southgate, Horatio (1840). Southgate, Horatio. Narrative of a tour through Armenia, Kurdistan, Persia and Mesopotamia. Tilt & Bogue.

Jacobites from the Syrians, whose chief city was damascus.

- Assyrian people

- .P. Brock, “St. Ephrem in the Eyes of Later Syriac Liturgical Tradition,” in Hugoye: Journal of Syriac Studies 2:1 (January, 1999), §12

- S.H. Griffith, “Christianity in Edessa and the Syriac-Speaking World: Mani, Bar Daysan, and Ephraem; the Struggle for Allegiance on the Aramean Frontier,” in Journal of the Canadian Society for Syriac Studies 2 (2002), p. 20 n. 76.

- 'Translation by L. van Rompay, “Jacob of Edessa and the early history of Edessa,” in G.J. Reinink & A.C. Klugkist (eds.), After Bardaisan: Studies on Continuity and Change in Syriac Christianity in Honour of Professor Han J. W. Drijvers (Groningen, 1999), p. 277.

- "Ministry of Interior to Admit Arameans to National Population Registry". Israel National News.

- Kamal S. Salibi, "The Lebanese Identity" Journal of Contemporary History 6.1, Nationalism and Separatism (1971:76-86).

- Maroon, Habib (31 March 2013). "A geneticist with a unifying message". Nature. Retrieved 3 October 2013.

- "70th Assyrian Convention Addresses Assyrian Autonomy in Iraq". www.aina.org.

- Charles E. Farhadian (editor), Christian Worship Worldwide (Eerdmans 2007), p. 77

- Robert M. Haddad, Syrian Christians in a Muslim Society: An Interpretation (Princeton University Press 2015), p. 4

- Paul Bradshaw, The Eucharistic Liturgies: Their evolution and interpretation (SPCK 2012), chapter 5

- Scott Fitzgerald Johnson (editor), The Oxford Handbook of Late Antiquity (Oxford University Press 2015), pp. 1007−1036

- Bryan D. Spinks, "Eastern Christian Liturgical Traditions" in Ken Parry (editor), The Blackwell Companion to Eastern Christianity (John Wiley & Sons 2008), pp. 339−340

- Augustine Casiday, The Orthodox Christian World (Routledge 2012), p. xv

- Jean Charbonnier, Christians in China: A.D. 600 to 2000 (Ignatius Press 2007), p. 111

- The 1994 Common Christological Declaration Between the Catholic Church and the Assyrian Church of the East declares that both the latter church's description ("Mother of Christ our God and Saviour") and the former's ("Mother of God" and "Mother of Christ") are legitimate and correct expressions of the same faith (Text of the Common Declaration).

- J. F. Bethune-Baker, Nestorius and His Teaching (Cambridge University Press 2014), chapter VI

- Walbert Bühlmann, Dreaming about the Church (Rowman & Littlefield 1987), pp. 111 and 164

- David Wilmshurst, The Ecclesiastical Organisation of the Church of the East, 1318-1913 (Peeters 2000), p. 4

- Sebastian P. Brock, Fire from Heaven: Studies in Syriac Theology and Liturgy (Ashgate 2006), p. 14

- Joost Jongerden, Jelle Verheij, Social Relations in Ottoman Diyarbekir, 1870-1915 (BRILL 2012), p. 21

- Gertrude Lowthian Bell, Amurath to Amurath (Heinemann 1911), p. 281

- Gabriel Oussani, "The Modern Chaldeans and Nestorians, and the Study of Syriac among them" in Journal of the American Oriental Society, vol. 22 (1901), p. 81; cf. Albrecht Classen (editor), East Meets West in the Middle Ages and Early Modern Times (Walter de Gruyter 2013), p. 704

- Horatio Southgate, Narrative of a Visit to the Syrian [Jacobite] Church of Mesopotamia (D. Appleton 1844), p. v

- The Indian branch of the Syriac Orthodox Church calls itself the Jacobite Syrian Christian Church

- "Monophysite - Christianity". Encyclopedia Britannica.

- "Arabization Policy Follows Assyrians Into the West". www.aina.org.

- John Joseph, The Modern Assyrians of the Middle East (BRILL 2000), p. 18

- J. F. Coakley, The Church of the East and the Church of England: A History of the Archbishop of Canterbury's Assyrian Mission (Clarendon Press 1992), p. 366

- Amirani, Shoku; Hegarty, Stephanie (12 May 2012). "Why is The Prophet so loved?" – via www.bbc.com.

- Judy Maltz, "Israeli Christian Community, Neither Arab nor Palestinian, Are Fighting to Save Identity" in Haaretz. 3 September 2014

- Jonathan Lis, "Israel Recognizes Aramean Minority in Israel as Separate Nationality" in Haaretz, 17 September 2014

- Ariel Cohen, "Israeli Greek Orthodox Church denounces Aramaic Christian nationality" in Jerusalem Post, 28 September 2014

- Frye, Richard Nelson (October 1992). "Assyria and Syria: Synonyms" (PDF). Journal of Near Eastern Studies. reprinted in Journal of the Assyrian Academic Studies 1997, Vol. 11, No. 2, pp.30–36. 51 (4): 281–285. doi:10.1086/373570. Archived from the original (PDF) on 31 July 2004.

- Joseph, John (1997). "Assyria and Syria: Synonyms?" (PDF). Journal of Assyrian Academic Studies. 11 (2): 37–43.

- Frye, Richard Nelson. "Reply to John Joseph" (PDF). Journal of Assyrian Academic Studies. 13 (1).

- Yildiz, Efrem. "The Assyrians A Historical and Current Reality: The Assyrians and the Babylonians: two peoples but one history?" (PDF). Journal of Assyrian Academic Studies. 13 (1).

- Joseph, John (1998). "The Bible and the Assyrians: It Kept their Memory Alive" (PDF). Journal of Assyrian Academic Studies. XII. (1): 70–76.

- Yana, George. "Myth vs Reality" (PDF). Journal of Assyrian Academic Studies. 14 (1): 78–82.

- Gewargis, Odisho (2002). "We Are Assyrians" (PDF). Journal of Assyrian Academic Studies. XVI (1). Archived from the original (PDF) on 21 April 2003.

- Parpola, Simo (2004). "National and Ethnic Identity in the Neo-Assyrian Empire and Assyrian Identity in Post-Empire Times" (PDF). Journal of Assyrian Academic Studies. 18 (2). Archived from the original (PDF) on 17 July 2011.

- Biggs, Robert (2005). "My Career in Assyriology and Near Eastern Archaeology" (PDF). Journal of Assyrian Academic Studies. Oriental Institute, University of Chicago†. 19 (1). Archived from the original (PDF) on 27 February 2008.

- Rollinger, Robert (2006). "The terms "Assyria" and "Syria" again" (PDF). Journal of Near Eastern Studies. University of Chicago Press, Chicago, IL, ETATS-UNIS (1942) (Revue). 65 (4): 283–287. doi:10.1086/511103.

- Berntsson, Martin (2003). "Assyrier eller syrianer? Om fotboll, identitet och kyrkohistoria" (PDF) (in Swedish). Gränser (Humanistdag-boken nr 16). pp. 47–52.

- Nordgren, Kenneth. "Vems är historien? Historia som medvetande, kultur och handling i det mångkulturella Sverige Doktorsavhandlingar inom den Nationella Forskarskolan i Pedagogiskt Arbete" (PDF) (in Swedish) (3). Archived from the original (PDF) on 6 November 2006. Cite journal requires

|journal=(help) - Sargon R. Michael, review of J. Joseph The Modern Assyrians of the Middle East, Zinda magazine (2002)

Bibliography

- Andersson, Stefan (1983). Assyrierna – En bok om präster och lekmän, om politik och diplomati kring den assyriska invandringen till Sverige (in Swedish). Falköping: Gummessons Tryckeri AB. ISBN 978-91-550-2913-5. OCLC 11532612.

- Göran Gunner; Sven Halvardson (2005). Jag behöver rötter och vingar: om assyrisk/syriansk identitet i Sverige (in Swedish). Skelleftea: Artos & Norma. ISBN 978-91-7217-080-3. OCLC 185176817.

- Joseph, John (2000). The Modern Assyrians of the Middle East – Encounters with Western Christian Missions, Archeologists & Colonial Powers. BRILL. ISBN 978-90-04-11641-2. OCLC 43615273.

- Kamal S. Salibi (2003). A House of Many Mansions: The History of Lebanon Reconsidered. London: I.B. Tauris. ISBN 978-1-86064-912-7. OCLC 51994034.

- Mirza Dawid Gewargis Malik (2006). The Throne of Saliq: The Condition of Assyrianism in the Era of the Incarnation of Our Lord, and Notes on the History of Assyria (in Syriac). Gorgias Press LLC. ISBN 978-1-59333-406-2. OCLC 76941895.

- Saggs, H.W.F. (1984). The Might That Was Assyria. Sidgwick & Jackson. ISBN 978-0-283-98961-2. OCLC 10569174.

External links

- Kelley L. Ross, Note on the Modern Assyrians, The Proceedings of the Friesian School

- Los Angeles Times (Orange County Edition), Assyrians Hope for U.S. Protection, 17 February 2003, p. B8.

- Sarhad Jammo, Contemporary Chaldeans and Assyrians: One Primordial Nation, One Original Church, Kaldu.org

- Edward Odisho, PhD, Assyrians, Chaldeans & Suryanis: We all have to hang together before we are hanged separately (2003)

- Aprim, Fred, The Assyrian Cause and the Modern Aramean Thorn (2004)

- Wilfred Alkhas, Neo-Assyrianism & the End of the Confounded Identity (2006)

- Nicholas Aljeloo, Who Are The Assyrians?, (2000)

- William Warda, Aphrim Barsoum's Role in distancing the Syrian Orthodox Church from its Assyrian Heritage, (2005)