Battle of Echoee

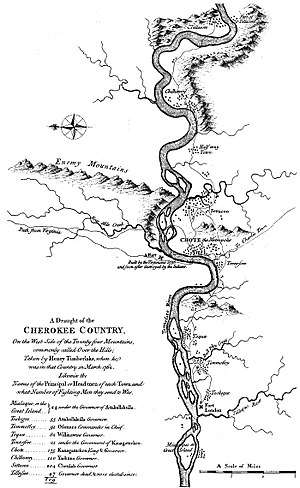

The Battle of Echoee, or Etchoe Pass, was a battle on June 27, 1760, between the British and colonial force under Archibald Montgomerie and a force of Cherokee warriors under Seroweh. The encounter took place near the present-day municipality of Otto, in Macon County, North Carolina.[3]

Background

With the outbreak of the French and Indian War in 1754, the Cherokee were sought out as allies by the British, eventually taking part in campaigns against Fort Duquesne (present day Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania) and the Shawnee of the Ohio Country. In exchange for the participation of the Cherokee warriors, the British agreed to build two forts to protect the Cherokee women, children and towns from the retaliation of the French and their Indian allies. The forts built by South Carolina were Fort Prince George, near Keowee on the Savannah River in the Lower Towns and Fort Loudoun, near Chota, where the Little Tennessee River and Tellico River converged, by the Overhill Towns. A third fort, built by Virginia, across the Little Tennessee near Chota was left unmanned.[4]

Ostenaco, a Cherokee leader, with 100 warriors joined Major Andrew Lewis with 200 Virginia Provincial troops in the depths of winter in February 1756. After six weeks, the expedition was out of supplies and had eaten their horses. The Cherokee, irritated by the performance of the Provincials decided to begin walking back towards Chota.

portrait by Francis Parsons, 1762,

at the Smithsonian Institution

The following year, the Cherokee joined a British army which was being put together in Pennsylvania under British General John Forbes. The expedition, which included British regular troops, Provincials from North Carolina, Virginia and Pennsylvania, along with Catawba, Tuscarora, and a few Creek and Chickasaw warriors, was aimed at forcing the French from their major fortification in western PA, Ft Duquesne.

The Forbes campaign was plagued with logistical problems. Having promised goods to the various Indian warriors for their assistance, and falling short, many warriors began leaving quite disgusted by June 1758. Provisions were promised to the warriors traveling home, many with their families. These goods were supposed to be obtained at forts which were located along their way back to their homelands.

On their way back, the Cherokee took some stray horses in Virginia to replace those they had lost. Virginia settlers got angry and banded together, pursuing the Cherokee, attacking them and killing, scalping and mutilating 20 of the Indians, later collecting the bounty offered for enemy scalps.[5] Although Dinwiddie, the lieutenant governor of Virginia, apologized some Virginians considered them horse thieves. Some Cherokees and Moytoy (Amo-adawehi) of Citico retaliated for the murders of Cherokee warriors at the hands of their colonial allies and the situation escalated.

The colonists' actions and Cherokee reactions began a domino effect that ended with the murders of Cherokee hostages at Fort Prince George near Keowee. These events ushered in a war which didn't end until 1761. The Cherokee were led by Standing Turkey, Aganstata (Oconostota) of Chota, Attakullakulla (Atagulgalu) of Tanasi, Ostenaco of Tomotley, Wauhatchie (Wayatsi) of the Lower Towns, and Round O of the Middle Towns. The Cherokee sought allies among the other Indian tribes and help from the French but received no practical aid and faced the British alone.

The new governor of South Carolina, William Henry Lyttelton, declared war on the Cherokee in 1759.[6] The governor embargoed all shipments of gunpowder to the Cherokee and raised an army of 1,100 provincial troops along with an artillery company under Christopher Gadsden which marched to confront the Lower Towns of the Cherokee. Desperate for ammunition for their fall and winter hunts, the Cherokee sent a peace delegation of moderate chiefs to negotiate. The thirty-two chiefs were taken prisoner, as hostages, and, escorted by the provincial army, were sent[7] to Fort Prince George and held in a tiny room only big enough for six people.[8] Three of the chiefs were released conditionally because Lyttelton thought this would ensure peace.

Lyttelton returned to Charleston, but the Cherokee were now quite angry, and continued to attack frontier settlements into 1760. In February 1760, they attacked Fort Prince George in an attempt to rescue their hostages. The fort's commander was killed. His replacement killed all of the hostages and fended off the attack. The Cherokee also attacked Fort Ninety Six, but it withstood the siege. Fort Loudoun was also put under siege; and several lesser posts in the South Carolina back-country quickly fell to Cherokee raids.

Governor Lyttelton appealed for help to Jeffrey Amherst, the British commander in North America. Amherst sent Archibald Montgomerie with an army of 1,300 to 1,500 troops[9] including 400 in four companies of the Royal Scots[10] and a 700-man battalion of the Montgomerie's Highlanders to South Carolina. His second in command was Major James Grant. The regulars were joined by some 300 mounted Carolina rangers, in seven troops, and 100 militia as well a party of 40 to 50 Catawba warriors.[11] The goal of the expedition was to subdue the Cherokee by razing their towns and crops, while relieving those posts invested by the Cherokee, in particular, Fort Loudoun. In late May the British had reached Fort Ninety-Six, Montgomerie's campaign razed some of the Cherokee Lower Towns, including Keowee, Estatoe and Sugar Town, killing or capturing around 100 Indians. He then relieved Fort Prince George offering to parley with the Cherokee who, having retreated to the Middle Towns, were no longer willing to negotiate.

Montgomerie waited ten days then prepared to march on the Middle Towns, some sixty miles northeast over very difficult terrain, both mountainous and forested. He had to leave behind his wagon transport which could not move beyond the Lower Towns and use improvised panniers and packsaddles for the horses of the baggage train.

Battle

portrait by Joshua Reynolds.

At some five miles from Etchoe, the lowest town in the Cherokee's middle settlements, Montgomerie's advanced guard of a company of Rangers was ambushed in a deep valley. Captain Morrison and a number of his Rangers were killed. Many of the Cherokee were armed with rifles which had a longer and more accurate range than the muskets the British fought with.[12] While accounts tell of the Indians making aimed shots, the British blazed away with ineffective platoon fire. Indian accounts speak of the British standing in 'heaps' and being shot down like turkeys. The Rangers especially performed badly, with Lieutenant Grant reporting that some fifty deserted before the march and the rest ran off when Morrison was killed.[13]

The Grenadier and the Light infantry companies moved forward to support the Rangers while the Royal Scots came forward on rising ground to the right of the Cherokee. The Royal Scots were thrown back into open ground by heavy rifle fire and it took some time to reform and fight off the Cherokee counter-attack. Montgomerie now extended his line on the left with the Highlanders, who turned the Indian right. The Indians retired from this advance and came into contact with the Royal Scots in a brisk encounter from which they retreated to a position on a hill from which they could not be dislodged. Montgomerie ordered an advance through the pass and on to the town, but some of the Cherokee ran to warn the inhabitants to leave. Some of the warriors had got around his flanks and attacked his pack animals and supply train whose loss would cripple the army. This attack was eventually driven off.[14]

Montgomerie found himself with a large number of seriously wounded men which he could neither leave behind if he advanced or retreated. He also lost many of his pack animals so that it was impossible to proceed any farther.[15] He had to abandon the advance along with a large quantity of supplies in order to provide pack horses to transport the wounded to safety. The British force retreated back to Fort Prince George. Montgomerie turned over supplies to the fort and left his most badly wounded. He then continued his withdrawal to Charleston. While his expedition was partially successful in destroying the Cherokee Lower Towns and relieving Fort Prince George, he had been halted and forced to withdraw at the Middle Towns and failed to relieve Fort Loudoun. By August he and his men sailed back to New York.

Aftermath

by Sir Joshua Reynolds, 1762.

The failure to relieve Fort Loudon forced the garrison to surrender with Captain Demeré and the garrison allowed to retain their arms and enough ammunition to make the trip back to the colony provided they left the remaining arms and stores of ammunition to the Cherokee led by Ostenaco. Its garrison marched out of the fort on August 9 with a Cherokee escort. The Indians entered the fort and found 10 bags of powder and ball buried and the cannon and small arms thrown in the river to keep them from the Cherokee. The Indians, angered by the broken agreement, went after the garrison.[16] The next morning the escort had drifted off and the garrison was attacked in the woods by perhaps 700 Indians.[17] Some 22 soldiers, equal to the number of Cherokee chief hostages killed at Fort Prince George, and 3 civilians were killed and 120 taken prisoners. Panic and consternation reigned in Charleston at the news. A truce of six months was agreed to during which peace attempts failed.

After a difficult winter for the Cherokee due to the loss of the Lower Towns' harvest and shortage of ammunition for hunting, as well as disease, Cherokee morale still remained high. However, Amherst had determined to launch a greater invasion of the Cherokee lands "to chastise the Cherokees [and] reduce them to the absolute necessity of suing for pardon,". James Grant was now in command with more regulars: the 1st, 17th and 22nd Regiments, a war-party of Mohawks and Stockbridge Indian scouts, Catawba and Chickasaw warriors; a large number of provincials under Colonel Middleton that included several who would gain fame during the American Revolution: William Moultrie, Charles Cotesworth Pinckney and Francis Marion and rangers. His force was more than 2,800 strong[18] and they were prepared for an extended campaign in the mountain and forest terrain with a supply train a mile long made up of 600 packhorses carrying a month's provisions and a large herd of cattle managed by a few score slaves.

Grant would be met by 1,000 Cherokee warriors on June 10, 1761, near the site of the previous battle of Echoee. The Indians again ambushed the column and this time concentrated on killing the pack animals. After six hours of long range skirmishing the Cherokee exhausted their limited ammunition and withdrew. Grant's force then proceeded to burn the fifteen Middle Towns and all the crops. Grant expressly ordered the troops to summarily execute any Indian man, woman or child they captured. Although, by July, Grant had marched his men to exhaustion with 300 too sick to walk, he had wrecked the Cherokee economy and made 4,000 inhabitants of the Middle Towns homeless and starving. In August 1761 the Cherokee sued for peace.[19] As a result of the war, Cherokee warrior strength estimated at 2,590 before the war in 1755[20] was now reduced by battle, Smallpox and starvation to 2,300.[21]

References

- South Carolina Gazette, 5–12 July 1760.

- Drake, p. 377.

- Anderson, William, "Etchoe, Battle of", Encyclopedia of North Carolina, William S. Powell, ed., (UNC Press 2006).

- Conley, Robert J..The Cherokee Nation: A History, University of New Mexico Press, 2005, ISBN 978-0-8263-3236-3, p. 46.

- Mooney, p. 41.

- Mooney, p. 42, Conley, p. 47.

- Anderson, p. 460.

- Conley, p. 47.

- Oliphant, p. 113. Hatley gives 1,200, p. 131.

- Woodward, p. 74, Drake, p. 376, Fortescue, p. 400.

- Anderson, p. 462, Keenan. p. 40.

- Woodward, p. 75, Hatley, p. 131.

- Hatley, p. 131.

- Oliphant, pp. 130–131.

- Anderson, p. 463.

- Conley, p. 52.

- Anderson, p. 464.

- Anderson, p. 466.

- Anderson, pp. 466–467.

- Mooney, p. 39, 2,590 in 1755; 5,000 in 1739 before the great smallpox epidemic.

- Mooney, p. 45.

Bibliography

- Anderson, Fred. Crucible of War: The Seven Years' War and the Fate of Empire in British North America, 1754–1766. New York: Knopf, 2000. ISBN 0-375-40642-5.

- Conley, Robert J..The Cherokee Nation: A History. Albuquerque: University of New Mexico Press, 2005, ISBN 978-0-8263-3236-3.

- Drake, Samuel Gardner. Biography and history of the Indians of North America, Boston, MDCCCLI.

- Fortescue J. W.. A History of the British Army. London: Macmillan, 1899, Vol. II.

- Hatley, Thomas. The Dividing Paths: Cherokees and South Carolinians through the Era of Revolution. New York: Oxford University Press, 1993.

- Mooney, James. Myths of the Cherokee and Sacred Formulas of the Cherokee. Nashville, Tenn.: Charles and Randy Elder-Booksellers, 1982.

- Oliphant, John. Peace and War on the Anglo-Cherokee Frontier, 1756–63. Baton Rouge, LA: Louisiana State University Press, 2001.

- Stewart, David, Major General. Sketches of the character, manners, and present state of the Highlanders, Vols 1 & 2. Edinburgh, 1825.

- Tortora, Daniel J. Carolina in Crisis: Cherokees, Colonists, and Slaves in the American Southeast, 1756–1763. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2015. ISBN 1-469-62122-3.

- Woodward, Grace Steele.The Cherokees. Norman: University of Oklahoma Press, 1963. ISBN 0-8061-1815-6.