Alans

The Alans (Latin: Alani) were an Iranian nomadic pastoral people of antiquity.[1][2][3][4][5]

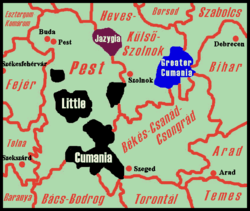

Alani | |

|---|---|

Map showing the migrations of the Alans | |

| Languages | |

| Scythian | |

| Related ethnic groups | |

| Ossetians |

| Part of a series on |

| Indo-European topics |

|---|

|

|

|

Philology

|

|

Origins |

|

Archaeology Pontic Steppe

Caucasus East Asia Eastern Europe Northern Europe Pontic Steppe Northern/Eastern Steppe Europe

South Asia Steppe Europe Caucasus India |

|

Peoples and societies Indo-Aryans Iranians

East Asia Europe East Asia Europe

Indo-Aryan Iranian

|

|

Religion and mythology

Indo-Aryan Iranian Others Europe

|

|

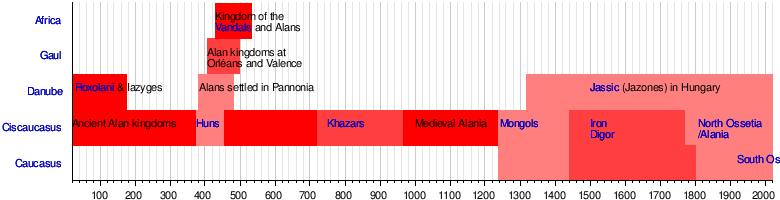

The name Alan is an Iranian dialectal form of Aryan.[1][2] Possibly related to the Massagetae, the Alans have been connected by modern historians with the Central Asian Yancai and Aorsi of Chinese and Roman sources, respectively.[6] Having migrated westwards and become dominant among the Sarmatians on the Pontic Steppe, they are mentioned by Roman sources in the 1st century AD.[1][2] At the time, they had settled the region north of the Black Sea and frequently raided the Parthian Empire and the Caucasian provinces of the Roman Empire.[7] From 215–250 AD, their power on the Pontic Steppe was broken by the Goths.[4]

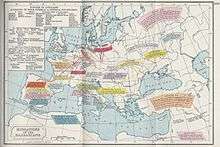

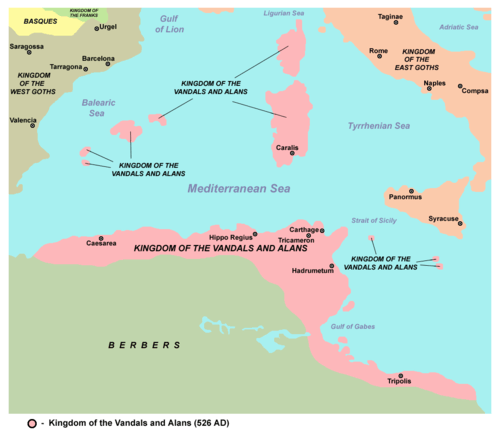

Upon the Hunnic defeat of the Goths on the Pontic Steppe around 375 AD, many of the Alans migrated westwards along with various Germanic tribes. They crossed the Rhine in 406 AD along with the Vandals and Suebi, settling in Orléans and Valence. Around 409 AD, they joined the Vandals and Suebi in the crossing of the Pyrenees into the Iberian Peninsula, settling in Lusitania and Carthaginensis.[8] The Iberian Alans were soundly defeated by the Visigoths in 418 AD and subsequently surrendered their authority to the Hasdingi Vandals.[9] In 428 AD, the Vandals and Alans crossed the Strait of Gibraltar into North Africa, where they founded a powerful kingdom which lasted until its conquest by the Byzantine Emperor Justinian I in the 6th century AD.[9]

The Alans who remained under Hunnic rule founded a powerful kingdom in the North Caucasus in the Middle Ages, which ended with the Mongol invasions in the 13th century AD. These Alans are said to be the ancestors of the modern Ossetians.[7]

The Alans spoke an Eastern Iranian language which derived from Scytho-Sarmatian and which in turn evolved into modern Ossetian.[2][10][11]

Name

The various forms of Alan – Greek: Ἀλανοί Alanoi; Chinese: 阿蘭聊 Alanliao (Pinyin) in the 2nd century,[12] 阿蘭 Alan in the 3rd century[13] and later Alanguo (阿蘭國)[14] – are derived from Iranian dialectal forms of Aryan.[1][2][15] This word was preserved in the modern Ossetian language in the form of Allon.[16][17] These and other variants of Aryan (such as Iran) were common self-designations of the Indo-Iranians, the common ancestors of the Indo-Aryans and Iranian peoples to whom the Alans belonged.

Rarer spellings include Alauni or Halani. The Alans were also known over the course of their history by another group of related names including the variations Asi, As, and Os (Romanian Iasi or Olani, Bulgarian Uzi, Hungarian Jász, Russian Jasy, Georgian Osi).[18] It is this name that is the root of the modern Ossetian.[19]

History

Timeline

Early Alans

The first mentions of names that historians link with the Alani appear at almost the same time in texts from the Mediterranean, Middle East and China.[10]

In the 1st century AD, the Alans migrated westwards from Central Asia, achieving a dominant position among the Sarmatians living between the Don River and the Caspian Sea.[4][5] The Alans are mentioned in the Vologeses inscription which reads that Vologeses I, the Parthian king between around 51 and 78 AD, in the 11th year of his reign, battled Kuluk, king of the Alani.[21] The 1st century AD Jewish historian Josephus supplements this inscription. Josephus reports in the Jewish Wars (book 7, ch. 7.4) how Alans (whom he calls a "Scythian" tribe) living near the Sea of Azov crossed the Iron Gates for plunder (72 AD) and defeated the armies of Pacorus, king of Media, and Tiridates, King of Armenia, two brothers of Vologeses I (for whom the above-mentioned inscription was made):

4. Now there was a nation of the Alans, which we have formerly mentioned somewhere as being Scythians, and living around Tanais and Lake Maeotis. This nation about this time laid a design of falling upon Media, and the parts beyond it, in order to plunder them; with which intention they treated with the king of Hyrcania; for he was master of that passage which king Alexander shut up with iron gates. This king gave them leave to come through them; so they came in great multitudes, and fell upon the Medes unexpectedly, and plundered their country, which they found full of people, and replenished with abundance of cattle, while nobody dared make any resistance against them; for Pacorus, the king of the country, had fled away for fear into places where they could not easily come at him, and had yielded up everything he had to them, and had only saved his wife and his concubines from them, and that with difficulty also, after they had been made captives, by giving a hundred talents for their ransom. These Alans therefore plundered the country without opposition, and with great ease, and proceeded as far as Armenia, laying waste all before them. Now, Tiridates was king of that country, who met them and fought them but was lucky not to have been taken alive in the battle; for a certain man threw a noose over him and would soon have drawn him in, had he not immediately cut the cord with his sword and escaped. So the Alans, being still more provoked by this sight, laid waste the country, and drove a great multitude of the men, and a great quantity of the other booty from both kingdoms, along with them, and then retreated back to their own country.

The fact that the Alans invaded Parthia through Hyrcania shows that at the time many Alans were still based north-east of the Caspian Sea.[4] By the early 2nd century AD the Alans were in firm control of the Lower Volga and Kuban.[4] These lands had earlier been occupied by the Aorsi and the Siraces, whom the Alans apparently absorbed, dispersed and/or destroyed, since they were no longer mentioned in contemporaneous accounts.[4] It is likely that the Alans' influence stretched further westwards, encompassing most of the Sarmatian world, which by then possessed a relatively homogenous culture.[4]

In 135 AD, the Alans made a huge raid into Asia Minor via the Caucasus, ravaging Media and Armenia.[4] They were eventually driven back by Arrian, the governor of Cappadocia, who wrote a detailed report (Ektaxis kata Alanoon or 'War Against the Alans') that is a major source for studying Roman military tactics.

From 215 to 250 AD, the Germanic Goths expanded south-eastwards and broke the Alan dominance on the Pontic Steppe.[4] The Alans however seem to have had a significant influence on Gothic culture, who became excellent horsemen and adopted the Alanic animal style art.[4] (The Roman Empire, during the chaos of the 3rd century civil wars, suffered damaging raids by the Gothic armies with their heavy cavalry before the Illyrian Emperors adapted to the Gothic tactics, reorganized and expanded the Roman heavy cavalry, and defeated the Goths under Gallienus, Claudius II and Aurelian).

After the Gothic entry to the steppe, many of the Alans seem to have retreated eastwards towards the Don, where they seem to have established contacts with the Huns.[4] Ammianus writes that the Alans were "somewhat like the Huns, but in their manner of life and their habits they are less savage."[4] Jordanes contrasted them with the Huns, noting that the Alans "were their equals in battle, but unlike them in their civilisation, manners and appearance".[4] In the late 4th century, Vegetius conflates Alans and Huns in his military treatise – Hunnorum Alannorumque natio, the "nation of Huns and Alans" – and collocates Goths, Huns and Alans, exemplo Gothorum et Alannorum Hunnorumque.[22]

The 4th century Roman historian Ammianus Marcellinus noted that the Alans were "formerly called Massagetae,"[23] while Dio Cassius wrote that "they are Massagetae."[4] It is likely that the Alans were an amalgamation of various Iranian peoples, including Sarmatians, Massagetae and Sakas.[4] Scholars have connected the Alans to the nomadic state of Yancai mentioned in Chinese sources.[6] The Yancai are first mentioned in connection with late 2nd century BC diplomat Zhang Qian's travels in Chapter 123 of Shiji (whose author, Sima Qian, died c. 90 BC).[6][24] The Yancai of Chinese records has again been equated with the Aorsi, a powerful Sarmatian tribe living between the Don River and the Aral Sea, mentioned in Roman records, in particular Strabo.[6]

Link to Yancai/Alanliao

The Later Han dynasty Chinese chronicle, the Hou Hanshu, 88 (covering the period 25–220 and completed in the 5th century), mentioned a report that the steppe land Yancai had become a vassal state of the Kangju and was now known as Alanliao (阿蘭聊)[25]

Y. A. Zadneprovskiy suggests that the Kangju subjugation of Yancai occurred in the 1st century BC, and that this subjugation caused various Sarmatian tribes, including the Aorsi, to migrate westwards, which played a major role in starting the Migration Period.[6][26] The 3rd century Weilüe also notes that Yancai was then known to be Alans, although they were no longer vassals of the Kangju.[27]

Migration to Gaul

Around 370, according to Ammianus, the peaceful relations between the Alans and Huns were broken, after the Huns attacked the Don Alans, killing many of them and establishing an alliance with the survivors.[4][28] These Alans successfully invaded the Goths in 375 together with the Huns.[4] They subsequently accompanied the Huns in their westward expansion.[4]

Following the Hunnic invasion in 370, other Alans, along with other Sarmatians, migrated westward.[4] One of these Alan groups fought together with the Goths in the decisive Battle of Adrianople in 378 AD, in which emperor Valens was killed.[4] As the Roman Empire continued to decline, the Alans split into various groups; some fought for the Romans while other joined the Huns, Visigoths or Ostrogoths.[4] A portion of the western Alans joined the Vandals and the Suebi in their invasion of Roman Gaul. Gregory of Tours mentions in his Liber historiae Francorum ("Book of Frankish History") that the Alan king Respendial saved the day for the Vandals in an armed encounter with the Franks at the crossing of the Rhine on December 31, 406). According to Gregory, another group of Alans, led by Goar, crossed the Rhine at the same time, but immediately joined the Romans and settled in Gaul.

Under Beorgor (Beorgor rex Alanorum), they moved throughout Gaul, till the reign of Petronius Maximus, when they crossed the Alps in the winter of 464, into Liguria, but were there defeated, and Beorgor slain, by Ricimer, commander of the Emperor's forces.[29][30]

In 442, after it became clear to Aetius that he could no longer rely upon the Huns for support, he turned to Goar and convinced him to move some of his people to settlements in the Orleanais in order to control the bacaudae of Armorica and to keep the Visigoths from expanding their territories northward across the Loire. Goar settled a substantial number of his followers in the Orleanais and the area to the north and personally moved his own capital to the city of Orleans.[31]

Under Goar, they allied with the Burgundians led by Gundaharius, with whom they installed the Emperor Jovinus as usurper. Under Goar's successor Sangiban, the Alans of Orléans played a critical role in repelling the invasion of Attila the Hun at the Battle of Châlons. In 463 the Alans defeated the Goths at the battle of Orléans, and they later defeated the Franks led by Childeric in 466.[32] Around 502-503 Clovis attacked Armorica but he was defeated by the Alans, however the Alans, who, like Clovis, were Christians, desired cordial relations with him to counterbalance the hostile Arian Visigoths who coveted the land north of the Loire. Therefore, an accord was arranged by which Clovis came to rule the various peoples of Armorica and the military strength of the area was integrated into the Merovingian military.[33]

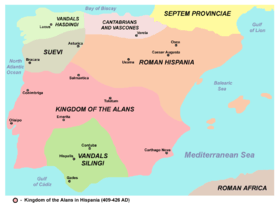

Hispania and Africa

Following the fortunes of the Vandals and Suebi into the Iberian peninsula (Hispania, comprising modern Portugal and Spain) in 409,[34] the Alans led by Respendial settled in the provinces of Lusitania and Carthaginensis.[35] The Kingdom of the Alans was among the first Barbarian kingdoms to be founded. The Siling Vandals settled in Baetica, the Suebi in coastal Gallaecia, and the Asding Vandals in the rest of Gallaecia. Although the newcomers controlled Hispania they were still a tiny minority among a larger Hispano-Roman population, approximately 200,000 out of 6,000,000.[8]

In 418 (or 426 according to some authors[36]), the Alan king, Attaces, was killed in battle against the Visigoths, and this branch of the Alans subsequently appealed to the Asding Vandal king Gunderic to accept the Alan crown. The separate ethnic identity of Respendial's Alans dissolved.[37] Although some of these Alans are thought to have remained in Iberia, most went to North Africa with the Vandals in 429. Later the rulers of the Vandal Kingdom in North Africa styled themselves Rex Wandalorum et Alanorum ("King of the Vandals and Alans").

There are some vestiges of the Alans in Portugal,[38] namely in Alenquer (whose name may be Germanic for the Temple of the Alans, from "Alan Kerk",[39] and whose castle may have been established by them; the Alaunt is still represented in that city's coat of arms), in the construction of the castles of Torres Vedras and Almourol, and in the city walls of Lisbon, where vestiges of their presence may be found under the foundations of the Church of Santa Luzia.

In the Iberian peninsula the Alans settled in Lusitania (Alentejo) and the Cartaginense provinces. They became known in retrospect for their massive hunting and fighting dog of Molosser type, the Alaunt, which they apparently introduced to Europe. The breed is extinct, but its name is carried by a Spanish breed of dog still called Alano, traditionally used in boar hunting and cattle herding. The Alano name, however, has historically been used for a number of dog breeds in a few European countries thought to descend from the original dog of the Alans, such as the German mastiff (Great Dane) and the French Dogue de Bordeaux, among others.

Medieval Alania

The Alans who remained in their original area of settlement north of the Caucasus (and for a time east of the Caspian Sea as well), came into contact and conflict with the Bulgars, the Gökturks, and the Khazars, who drove most of them from the plains and into the mountains.[40]

The Alans converted to Byzantine Orthodoxy in the first quarter of the 10th century, during the patriarchate of Nicholas I Mystikos. Al-Mas‘udi reports that they apostasized in 932, but this seems to have been short-lived. The Alans are collectively mentioned as Byzantine-rite Christians in the 13th century.[40] The Caucasian Alans were the ancestors of the modern Ossetians, whose ethnonym derives from the name Ās (very probably the ancient Aorsi; al-Ma'sudi mentions al-Arsiyya as guards among the Khazars, and the Rus' called the Alans Yasi), a sister tribe of the Alans. The Armenian Geography uses the name Ashtigor for the most westerly located Alans, a name which survives as Digor and still refers to the western division of the Ossetians. Furthermore, in Ossetian, Asi refers to the region around Mount Elbrus, where they probably formerly lived.[40]

Some of the other Alans remained under the rule of the Huns. Those of the eastern division, though dispersed about the steppes until late medieval times, were forced by the Mongols into the Caucasus, where they remain as the Ossetians. Between the 9th and 12th centuries, they formed a network of tribal alliances that gradually evolved into the Christian kingdom of Alania. Most Alans submitted to the Mongol Empire in 1239–1277. They participated in Mongol invasions of Europe and the Song dynasty in Southern China, and the Battle of Kulikovo under Mamai of the Golden Horde.[41]

In 1253, the Franciscan monk William of Rubruck reported numerous Europeans in Central Asia. It is also known that 30,000 Alans formed the royal guard (Asud) of the Yuan court in Dadu (Beijing). Marco Polo later reported their role in the Yuan dynasty in his book Il Milione. It is said that those Alans contributed to a modern Mongol clan, Asud. John of Montecorvino, archbishop of Dadu (Khanbaliq), reportedly converted many Alans to Roman Catholic Christianity in addition to Armenians in China.[42][43] In Poland and Lithuania, Alans were also part of the powerful Clan of Ostoja.

Against the Alans and the Cumans (Kipchaks), the Mongols used divide-and-conquer tactics by first telling the Cumans to stop allying with the Alans and, after the Cumans followed their suggestion, the Mongols then attacked the Cumans[44] after defeating the Alans.[45] Alans were recruited into the Mongol forces with one unit called "Right Alan Guard" which was combined with "recently surrendered" soldiers, Mongols, and Chinese soldiers stationed in the area of the former Kingdom of Qocho and in Besh Balikh the Mongols established a Chinese military colony led by Chinese general Qi Kongzhi (Ch'i Kung-chih).[46] Alan and Kipchak guards were used by Kublai Khan.[47] In 1368 at the end of the Yuan dynasty in China Toghan Temür was accompanied by his faithful Alan guards.[48] Mangu enlisted in his bodyguard half the troops of the Alan prince, Arslan, whose younger son Nicholas took a part in the expedition of the Mongols against Karajang (Yunnan). This Alan imperial guard was still in existence in 1272, 1286 and 1309, and it was divided into two corps with headquarters in the Ling pei province (Karakorúm).[49] In 1254 Rubruquis found a Russian deacon amongst the other Christians at Karakorum. The reason why the earlier Persian word tersa was gradually abandoned by the Mongols in favour of the Syro-Greek word arkon, when speaking of Christians, manifestly is that no specifically Greek Church was ever heard of in China until the Russians had been conquered; besides, there were large bodies of Russian and Alan guards at Peking throughout the last half of the thirteenth and first half of the fourteenth century, and the Catholics there would not be likely to encourage the use of a Persian word which was most probably applicable in the first instance to the Nestorians they found so degenerated.[50] The Alan guards converted to Catholicism as reported by Odorico.[51] They were a "Russian guard".[52]

It is believed that some Alans resettled to the North (Barsils), merging with Volga Bulgars and Burtas, eventually transforming to Volga Tatars.[53] It is supposed that the Iasi, a group of Alans founded a town in the northeast of Romania (about 1200–1300), near the Prut river, called Iași. The latter became the capital of ancient Moldavia in the Middle Ages.[54]

Alan mercenaries were involved in the affair with the Catalan Company.[55][56]

Later history

Descendants of the Alans, who live in the autonomous republics of Russia and Georgia, speak the Ossetian language which belongs to the Northeastern Iranian language group and is the only remnant of the Scytho-Sarmatian dialect continuum, which once stretched over much of the Pontic steppe and Central Asia. Modern Ossetian has two major dialects: Digor, spoken in the western part of North Ossetia; and Iron, spoken in the rest of Ossetia. A third branch of Ossetian, Jassic (Jász), was formerly spoken in Hungary. The literary language, based on the Iron dialect, was fixed by the national poet, Kosta Khetagurov (1859–1906).

Physical appearance

The fourth-century Roman historian Ammianus Marcellinus wrote that the Alans were tall, and blond:

Nearly all the Alani are men of great stature and beauty; their hair is somewhat yellow, their eyes are terribly fierce.[57]

Genetics

In a study conducted in 2014 by V. V. Ilyinskyon on bone fragments from 10 Alanic burials on the Don River, DNA could be abstracted from a total of seven. Four of them turned out to belong to yDNA Haplogroup G2 and six of them had mtDNA I. The fact that many of the samples share the same y- and mtDNA raises the possibility that the tested individuals belonged to the same tribe or even were close relatives. Nevertheless, this is a strong argument for direct Alan ancestry of Ossetians and against the hypothesis that Ossetians are alanized Caucasic speakers, since the major Haplogroup among Ossetians is G2 also.[58]

In 2015 the Institute of Archaeology in Moscow conducted research on various Sarmato-Alan and Saltovo-Mayaki culture Kurgan burials. In this analysis, the two Alan samples from the 4th to 6th century AD had yDNAs G2a-P15 and R1a-z94, while from the three Sarmatian samples from 2nd to 3rd century AD two had yDNA J1-M267 and one possessed R1a.[59] Also, the three Saltovo-Mayaki samples from 8th to 9th century AD turned out to have yDNAs G, J2a-M410 and R1a-z94 respectively.[60]

A genetic study published in Nature in May 2018 examined the remains of six Alans buried in the Caucasus from ca. 100 AD to 1400 AD. The sample of Y-DNA extracted belonged to haplogroup R1 and haplogroup Q-M242. One of the Q-M242 samples found in Beslan, North Ossetia from 200 AD found 4 relatives among Chechens from the Shoanoy Teip.[61] The samples of mtDNA extracted belonged to HV2a1, U4d3, X2f, H13a2c, H5, and W1.[62]

Archaeology

Archaeological finds support the written sources. P. D. Rau (1927) first identified late Sarmatian sites with the historical Alans. Based on the archaeological material, they were one of the Iranian-speaking nomadic tribes that began to enter the Sarmatian area between the middle of the 1st and the 2nd centuries.

Language

The ancient language of the Alans was an Eastern Iranian dialect either identical, or at least closely related, to ancient Eastern Iranian languages.[63] This is confirmed by comparison of the word for horse in various Indo-Iranian languages and the reconstructed Alanic word for horse:[64]

| Language | Affiliation | Horse |

|---|---|---|

| Alanic | *aspa | |

| Khotanese | Northeastern Iranian | aśśa |

| Ossetian | Northeastern Iranian | efs |

| Wakhi | Northeastern Iranian | yaš |

| Yaghnobi | Northeastern Iranian | asp |

| Avestan | Southeastern Iranian | aspa |

| Balochi | Northwestern Iranian | asp |

| Kurdi | Western Iranian | asp |

| Median | Northwestern Iranian | aspa |

| Old Persian | Southwestern Iranian | asa |

| Middle Persian | Southwestern Iranian | asp |

| Persian | Southwestern Iranian | asb |

| Sanskrit | Indo-Aryan | áśva |

Religion

Prior to their Christianisation, the Alans were Indo-Iranian polytheists, subscribing either to the poorly understood Scythian pantheon or to a polytheistic form of Zoroastrianism. Some traditions were directly inherited from the Scythians, like embodying their dominant god in elaborate rituals.[65]

In the 4th–5th centuries the Alans were at least partially Christianized by Byzantine missionaries of the Arian church. In the 13th century, invading Mongol hordes pushed the eastern Alans further south into the Caucasus, where they mixed with native Caucasian groups and successively formed three territorial entities each with different developments. Around 1395 Timur's army invaded the Northern Caucasus and massacred much of the Alanian population.

As time went by, Digor in the west came under Kabard and Islamic influence. It was through the Kabardians (an East Circassian tribe) that Islam was introduced into the region in the 17th century. After 1767, all of Alania came under Russian rule, which strengthened Orthodox Christianity in that region considerably. A substantial minority of today's Ossetians are followers of the traditional Ossetian religion.

See also

- Roxolani, possibly a sub-set of the Alans

- List of ancient Iranian peoples

References

Citations

- Golden 2009.

- Abaev & Bailey 1985, pp. 801–803.

- Waldman & Mason 2006, pp. 12–14

- Brzezinski & Mielczarek 2002, pp. 10–11

- Zadneprovskiy 1994, pp. 467–468

- Zadneprovskiy 1994, pp. 465–467

- "Alani". Encyclopædia Britannica Online. 2015. Retrieved 1 January 2015.

- "Spain: Visigothic Spain to c. 500". Encyclopædia Britannica Online. Encyclopædia Britannica, Inc. 2015. Retrieved 1 January 2015.

- "Vandal". Encyclopædia Britannica Online. Encyclopædia Britannica, Inc. 2015. Retrieved 1 January 2015.

- Alemany 2000, p. ?.

- For ethnogenesis, see Walter Pohl, "Conceptions of Ethnicity in Early Medieval Studies" Debating the Middle Ages: Issues and Readings, ed. Lester K. Little and Barbara H. Rosenwein, (Blackwell), 1998, pp 13–24) (On-line text).

- The Hou Hanshu

- The Weilüe

- Kozin, S.A., Sokrovennoe skazanie, M.-L., 1941. p.83-4

- Alemany 2000, p. 3.

- Abayev V. I. Ossetian language and folklore. М.—Л., 1949. p. 156.

- Abaev V. I. Historical-Etymological Dictionary of Ossetian Language. V. 1. М.—Л., 1958. p. 47-48.

- Sergiu Bacalov, Medieval Alans in Moldova / Consideraţii privind olanii (alanii) sau iaşii din Moldova medievală. Cu accent asupra acelor din regiunea Nistrului de Jos https://bacalovsergiu.files.wordpress.com/2016/05/download-sergiu-bacalov-considerac5a3ii-privind-olanii-alanii-sau-iac59fii-din-moldova-medievalc483.pdf)

- Alemany 2000, pp. 5–7.

- "Scythian - ancient people". britannica.com. Retrieved 8 May 2018.

- Vologeses inscription.

- Vegetius 3.26, noted in passing by T.D. Barnes, "The Date of Vegetius" Phoenix 33.3 (Autumn 1979, pp. 254–257) p. 256. "The collocation of these three barbarian races does not recur a generation later", Barnes notes, in presenting a case for a late 4th-century origin for Vegetius' treatise.

- Ammianus Marcellinus. Roman History. Book XXXI. II. 12

- Watson, Burton trans. 1993. Records of the Grand Historian by Sima Qian. Han Dynasty II. (Revised Edition), p. 234. Columbia University Press. New York. ISBN 0-231-08166-9; ISBN 0-231-08167-7 (pbk.)

- Hill, John E. 2003. "Annotated Translation of the Chapter on the Western Regions according to the Hou Hanshu." Revised Edition – to be published soon.

- Zadneprovskiy 1994, pp. 463–464

- For an earlier version of this translation

- Giovanni de Marignolli, "John De' Marignolli and His Recollections of Eastern Travel", in Cathay and the Way Thither: Being a Collection of Medieval Notices of China, Volume 2, ed. Henry Yule (London: The Hakluyt Society, 1866), 316–317.

- Isaac Newton, Observations on Daniel and The Apocalypse of St. John (1733).

- Paul the Deacon, Historia Romana, XV, 1.

- Bachrach, Bernard S. (1973). A History of the Alans in the West. U of Minnesota Press. p. 63. ISBN 9780816656998.

- Bachrach, Bernard S. (1973). A History of the Alans in the West. U of Minnesota Press. p. 77. ISBN 9780816656998.

- Bachrach, Bernard S. (1972). Merovingian Military Organization, 481-751. U of Minnesota Press. p. 10. ISBN 9780816657001.

- Historical Atlas of the Classical World, 500 BC–AD 600. Barnes & Noble Books. 2000. p. 2.16. ISBN 978-0-7607-1973-2.

- "Alani Lusitaniam et Carthaginiensem provincias, et Wandali cognomine Silingi Baeticam sortiuntur" (Hydatius)

- Castritius, 2007

- For another rapid disintegration of an ethne in the Early Middle Ages, see Avars. (Pohl 1998:17f).

- Milhazes, José. Os antepassados caucasianos dos portugueses Archived 2016-01-01 at the Wayback Machine – Rádio e Televisão de Portugal in Portuguese.

- Ivo Xavier Fernándes. Topónimos e gentílicos, Volume 1, 1941, p. 144.

- Barthold, W.; Minorsky, V. (1986). "Alān". The Encyclopedia of Islam, New Edition, Volume I: A–B. Leiden and New York: BRILL. p. 354. ISBN 978-90-04-08114-7.

- Handbuch Der Orientalistik By Agustí Alemany, Denis Sinor, Bertold Spuler, Hartwig Altenmüller, pp. 400–410

- Roux, p. 465

- Christian Europe and Mongol Asia: First Medieval Intercultural Contact Between East and West

- Sinor, Denis. 1999. "The Mongols in the West". Journal of Asian History 33 (1). Harrassowitz Verlag: 1–44. https://www.jstor.org/stable/41933117.

- Halperin, Charles J.. 2000. "The Kipchak Connection: The Ilkhans, the Mamluks and Ayn Jalut". Bulletin of the School of Oriental and African Studies, University of London 63 (2). Cambridge University Press: 235. https://www.jstor.org/stable/1559539.

- Morris Rossabi (1983). China Among Equals: The Middle Kingdom and Its Neighbors, 10th–14th Centuries. University of California Press. pp. 255–. ISBN 978-0-520-04562-0.

- David Nicolle (January 2004). The Mongol Warlords: Genghis Khan, Kublai Khan, Hulegu, Tamerlane. Brockhampton Press. p. 85. ISBN 978-1-86019-407-8.

- Arthur Thomas Hatto (1991). Archivum Eurasiae Medii Aevi. Peter de Ridder Press. p. 36.

- Sir Henry Yule (1915). Cathay and the Way Thither, Being a Collection of Medieval Notices of China. Asian Educational Services. pp. 187–. ISBN 978-81-206-1966-1.

- Edward Harper Parker (1905). China and religion. E. P. Dutton. pp. 232–.

- Lauren Arnold (1999). Princely Gifts and Papal Treasures: The Franciscan Mission to China and Its Influence on the Art of the West, 1250–1350. Desiderata Press. pp. 79–. ISBN 978-0-9670628-0-8.

- John Makeham (2008). China: The World's Oldest Living Civilization Revealed. Thames & Hudson. p. 269. ISBN 978-0-500-25142-3.

- (in Russian) Тайная история татар Archived 2007-09-27 at the Wayback Machine

- A. Boldur, Istoria Basarabiei, p. 20

- Jessee, Scott, and Anatoly Isaenko. 2013. "The Military Effectiveness of Alan Mercenaries in Byzantium, 1301–1306". In Journal of Medieval Military History: Volume XI, edited by Clifford J. Rogers, Kelly DeVries, and John France, 11:107–32. Boydell & Brewer. https://www.jstor.org/stable/10.7722/j.ctt31njvf.9.

- Rogers, Clifford J., Kelly DeVries, and John France, eds.. 2013. Journal of Medieval Military History: Volume XI. Edited by Clifford J. Rogers, Kelly DeVries, and John France. Vol. 11. Boydell & Brewer. https://www.jstor.org/stable/10.7722/j.ctt31njvf.

- Ammianus Marcellinus. Roman History. Book XXXI. II. 21.

- Reshetova, Irina; Afanasiev, Gennady. "Афанасьев Г.Е., Добровольская М.В., Коробов Д.С., Решетова И.К. О культурной, антропологической и генетической специфике донских алан // Е.И. Крупнов и развитие археологии Северного Кавказа. М. 2014. С. 312-315". Cite journal requires

|journal=(help) - "ДДНК Сарматы, Аланы".

- Reshetova, Irina; Afanasiev, Gennady. "Афанасьев Г.Е., Вень Ш., Тун С., Ван Л., Вэй Л., Добровольская М.В., Коробов Д.С., Решетова И.К., Ли Х.. Хазарские конфедераты в бассейне Дона // Естественнонаучные методы исследования и парадигма современной археологии. М. 2015. С.146-153". Cite journal requires

|journal=(help) - https://www.yfull.com/tree/Q-YP4000/

- Damgaard et al. 2018.

- Mallory, J. P.; Adams, Douglas Q. (1997). Encyclopedia of Indo-European Culture. Taylor & Francis. ISBN 9781884964985.

- Abaev, Vasiliĭ Ivanovich; l'Oriente, Istituto italiano per l'Africa e (1998). Studia iranica et alanica (in Russian). Istituto italiano per l'Africa e l'Oriente.

- Sulimirski, T. (1985). "The Scyths" in: Fisher, W. B. (Ed.) The Cambridge History of Iran, Vol. 2: The Median and Achaemenian Periods. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-20091-1. pp. 158–159.

Sources

- Abaev, V.I.; Bailey, H.W. (1985). "ALANS". Encyclopaedia Iranica, Vol. I, Fasc. 8. pp. 801–803.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Alemany, Agustí (2000). Sources on the Alans: A Critical Compilation. BRILL. ISBN 978-90-04-11442-5.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Bernard S. Bachrach, A History of the Alans in the West, from their first appearance in the sources of classical antiquity through the early Middle Ages, University of Minnesota Press, 1973 ISBN 0-8166-0678-1

- Bachrach, Bernard S. "The Origin of Armorican Chivalry." Technology and Culture, Vol. 10, No. 2. (Apr., 1969), pp. 166–171.

- Brzezinski, Richard; Mielczarek, Mariusz (2002). The Sarmatians, 600 BC-AD 450. Osprey Publishing. ISBN 978-1841764856. Retrieved 7 June 2015.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Castritius, H. 2007. Die Vandalen. Kohlhammer Verlag.

- Damgaard, P. B.; et al. (May 9, 2018). "137 ancient human genomes from across the Eurasian steppes". Nature. Nature Research. 557 (7705): 369–373. doi:10.1038/s41586-018-0094-2. PMID 29743675. Retrieved April 11, 2020.

- Golb, Norman and Omeljan Pritsak, Khazarian Hebrew Documents of the Tenth Century. Ithaca: Cornell Univ. Press, 1982.

- Golden, Peter B. (2009). "Alāns". In Fleet, Kate; Krämer, Gudrun; Matringe, Denis; Nawas, John; Rowson, Everett (eds.). Encyclopaedia of Islam, THREE. Brill Online. doi:10.1163/1573-3912_ei3_COM_22193. ISSN 1873-9830.

- Hill, John E. 2003. "Annotated Translation of the Chapter on the Western Regions according to the Hou Hanshu." 2nd Draft Edition.

- Hill, John E. 2004. The Peoples of the West from the Weilüe 魏略 by Yu Huan 魚豢: A Third Century Chinese Account Composed between 239 and 265 AD. Draft annotated English translation.

- Yu, Taishan. 2004. A History of the Relationships between the Western and Eastern Han, Wei, Jin, Northern and Southern Dynasties and the Western Regions. Sino-Platonic Papers No. 131 March 2004. Dept. of East Asian Languages and Civilizations, University of Pennsylvania.

- Waldman, Carl; Mason, Catherine (2006). Encyclopedia of European Peoples. Infobase Publishing. ISBN 978-1438129181. Retrieved January 16, 2015.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Zadneprovskiy, Y. A. (1 January 1994). "The Nomads of Northern Central Asia After The Invasion of Alexander". In Harmatta, János (ed.). History of Civilizations of Central Asia: The Development of Sedentary and Nomadic Civilizations, 700 B. C. to A. D. 250. UNESCO. pp. 457–472. ISBN 978-9231028465. Retrieved 29 May 2015.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)