Grigory Zinoviev

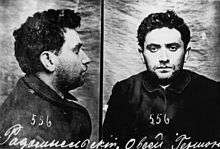

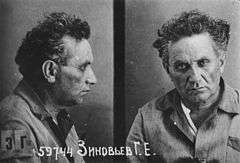

Grigory Yevseyevich Zinoviev[lower-alpha 1] (23 September [O.S. 11 September] 1883 – 25 August 1936), born Hirsch Apfelbaum, known also under the name Ovsei-Gershon Aronovich Radomyslsky, was a Bolshevik revolutionary and a Soviet Communist politician. Zinoviev was one of the seven members of the first Politburo, founded in 1917 in order to manage the Bolshevik Revolution: Lenin, Zinoviev, Kamenev, Trotsky, Stalin, Sokolnikov and Bubnov.[1] Zinoviev is best remembered as the longtime head of the Communist International and the architect of several failed attempts to transform Germany into a communist country during the early 1920s. He was in competition against Joseph Stalin, who eliminated him from the Soviet political leadership in 1925, followed by removal from the Petrograd Soviet in 1926. He joined a secret bloc with Leon Trotsky against Stalin in 1932, but probably quit it after again re-joining the party.

Grigory Zinoviev | |

|---|---|

Григо́рий Зино́вьев | |

.jpg) Zinoviev in 1920 | |

| Chairman of the Communist International | |

| In office 2 March 1919 – 22 November 1926 | |

| Preceded by | position created |

| Succeeded by | Nikolai Bukharin |

| Chairman of the Petrograd Soviet | |

| In office 13 December 1917 – 26 March 1926 | |

| Preceded by | Leon Trotsky |

| Succeeded by | Office abolished |

| Full member of the 6th, 10th, 11th, 12th, 13th, 14th Politburo | |

| In office 10 October – 29 November 1917 | |

| In office 16 March 1921 – 2 June 1924 | |

| Candidate member of the 8th, 9th Politburo | |

| In office 25 March 1919 – 16 March 1921 | |

| Personal details | |

| Born | Hirsch Apfelbaum 23 September 1883 Yelizavetgrad, Russian Empire |

| Died | 25 August 1936 (aged 52) Moscow, Russian SFSR, Soviet Union |

| Nationality | Russian (1883–1936) Soviet (1917–1936) |

| Political party | RSDLP (1901–1903) RSDLP (Bolsheviks) (1903–1912) Russian Communist Party (Bolsheviks) (1912–1927, 1928–1932, 1933–1934) |

He was a chief defendant in a 1936 show trial, the Trial of the Sixteen, that marked the start of the Great Purge in the USSR and resulted in his execution the day after his conviction in August 1936.

Zinoviev was also the alleged author of the Zinoviev letter to British communists, urging revolution, and published just before the 1924 general election. The message is widely dismissed as a forgery.[2]

Biography

Before the 1917 Revolution (1901–17)

Gregory Zinoviev was born in Yelizavetgrad, Russian Empire (now Kropyvnytskyi, Ukraine), to Jewish dairy farmers, who educated him at home. Between 1924 and 1934 the city was known as Zinovyevsk (Ukrainian: Зінов'євськ[zʲinɔvɛ́vsʲk]). Gregory Zinoviev was known in early life under Apfelbaum or Radomyslsky. He later adopted several designations, such as Shatski, Grigoriev, Grigori and Zinoviev, by the two last of which he is most frequently called.[3] He studied philosophy, literature and history. He became interested in politics and joined the Russian Social Democratic Labour Party (RSDLP) in 1901. He was a member of its Bolshevik faction from the time of its creation in 1903. Between 1903 and the fall of the Russian Empire in February 1917, he was a leading Bolshevik and one of Vladimir Lenin's closest associates, working both within Russia and abroad as circumstances permitted. He was elected to the RSDLP's Central Committee in 1907 and sided with Lenin in 1908 when the Bolshevik faction split into Lenin's supporters and Alexander Bogdanov's followers. Zinoviev remained Lenin's constant aide-de-camp and representative in various socialist organizations until 1917.

1917

Zinoviev spent the first three years of World War I in Switzerland. After the Russian monarchy was overthrown during the February Revolution, he returned to Russia in April 1917 in a sealed train with Lenin and other revolutionaries opposed to the war. He remained a part of the Bolshevik leadership throughout most of that year and spent time with Lenin after being forced into hiding in the period following the July Days. However, Zinoviev and Lenin soon had a falling out over Zinoviev's opposition to Lenin's call for an open rebellion against the Provisional Government. On 10 October 1917 (Julian calendar), he and Lev Kamenev were the only two Central Committee members to vote against an armed revolt. Their publication of an open letter opposed the use of force enraged Lenin, who demanded their expulsion from the party.[4] On 29 October 1917 (Julian calendar), immediately after the Bolshevik seizure of power during the October Revolution, the executive committee of the national railroad labor union, Vikzhel, threatened a national strike unless the Bolsheviks shared power with other socialist parties and dropped Lenin and Leon Trotsky from the government. Zinoviev, Kamenev, and their allies in the Bolshevik Central Committee argued that the Bolsheviks had no choice but to start negotiations since a railroad strike would cripple their government's ability to fight the forces that were still loyal to the overthrown Provisional Government. Although Zinoviev and Kamenev briefly had the support of a Central Committee majority and negotiations were started, a quick collapse of the anti-Bolshevik forces outside Petrograd allowed Lenin and Trotsky to convince the Central Committee to abandon the negotiating process. In response, Zinoviev, Kamenev, Alexei Rykov, Vladimir Milyutin, and Victor Nogin resigned from the Central Committee on November 4, 1917 (Julian calendar). The following day, Lenin wrote a proclamation calling Zinoviev and Kamenev "deserters".[5] He never forgot this conflict, eventually making an ambiguous reference to their "October episode" in his Testament.[6]

The Civil War (1918–20)

Zinoviev soon returned to the fold and was once again elected to the Central Committee at the VII Party Congress on March 8, 1918. He was put in charge of the Petrograd (Saint Petersburg before 1914, Leningrad 1924–91) city and regional government.

Sometime in 1918, while Ukraine was under German occupation, the rabbis of Odessa ceremonially anathematized (pronounced herem against) Trotsky, Zinoviev, and other Bolshevik leaders of Jewish descent in the synagogue.[7]

Shortly after the assassination of Petrograd Cheka leader Moisei Uritsky in August 1918 and the commencement of the five year Red Terror period of political repression and mass killings, Zinoviev said:

To overcome our enemies we must have our own socialist militarism. We must carry along with us 90 million out of the 100 million of Soviet Russia's population. As for the rest, we have nothing to say to them. They must be annihilated.[8]

He became a non-voting member of the ruling Politburo when it was created after the VIII Congress on 25 March 1919. He also became the Chairman of the Executive Committee of the Comintern when it was created in March 1919. It was in this capacity he presided over the Congress of the Peoples of the East in Baku in September 1920[9] and gave his famous four-hour speech in German at the Halle congress of the Independent Social Democratic Party of Germany in October 1920.[10]

Zinoviev was responsible for Petrograd's defence during two periods of intense clashes with White forces in 1919. Trotsky, who was in overall charge of the Red Army during the Russian Civil War, thought little of Zinoviev's leadership, which aggravated their strained relationship.

Rise to the top (1921–23)

In early 1921, when the Communist Party was split into several factions, and policy disagreements were threatening the unity of the Party. Zinoviev supported Lenin's faction. As a result, Zinoviev was made a full member of the Politburo after the Xth Party Congress on March 16, 1921, while members of other factions, such as Nikolai Krestinsky, were dropped from the Politburo and the Secretariat.

Zinoviev was one of the most influential figures in the Soviet leadership during Lenin's final illness in 1922–23 and immediately after his death in January 1924. He delivered the Central Committee's reports to the XIIth and XIIIth Party Congresses in 1923 and 1924, respectively, something that Lenin had previously done. He was also considered one of the Communist Party's leading theoreticians. As head of the Comintern, Zinoviev deserved most of the blame for the failures of several Communist attempts at seizing power in Germany during the early 1920s. Still, he managed to shift it to Karl Radek, the Comintern's representative in Germany at the time. One of the main functions of the Comintern was Bolshevization, whereby the proletarian revolution was postponed, and an emphasis was put on unconditional support for the Kremlin's foreign policy. The Comintern closely supervised the many national parties, and reorganized them along Soviet lines, with a healthy dose of Soviet political rhetoric as well.[11]

With Stalin and Kamenev against Trotsky (1923–24)

During Lenin's final illness, Zinoviev, his close associate Kamenev and Joseph Stalin formed a ruling 'triumvirate' (or 'troika') in the Communist Party, playing a key role in the marginalization of Leon Trotsky. The triumvirate carefully managed the intra-party debate and delegate-selection process in autumn 1923, during the run-up to the XIIIth Party Conference, and secured the vast majority of the seats. The Conference, held in January 1924 just before Lenin's death, denounced Trotsky and Trotskyism. Some of Trotsky's supporters suffered demotion or reassignment in the wake of his defeat, and Zinoviev's power and influence seemed at its zenith. However, as subsequent events showed, his real power base was limited to the Petrograd/Leningrad Party organization, while the rest of the Communist Party apparatus came increasingly under Stalin's control.

After Trotsky's defeat at the XIIIth Conference, tensions between Zinoviev and Kamenev, on the one hand, and Stalin on the other became more pronounced and threatened to end their alliance. Nevertheless, Zinoviev and Kamenev helped Stalin retain his position as General Secretary of the Central Committee at the XIIIth Party Congress in May–June 1924 during the first Lenin's Testament controversy.

After a brief lull in the summer of 1924, Trotsky published Lessons of October, an extensive summary of the events of 1917. In the article, Trotsky described Zinoviev's and Kamenev's opposition to the Bolshevik seizure of power in 1917, something that the two would have preferred left unmentioned. This started a new round of intra-party struggle, with Zinoviev and Kamenev once again allied with Stalin against Trotsky. They and their supporters accused Trotsky of various mistakes and worse during the Russian Civil War. They damaged his military reputation so much that he was forced to resign as People's Commissar of Army and Fleet Affairs and Chairman of the Revolutionary Military Council in January 1925. Zinoviev demanded Trotsky's expulsion from the Communist Party, but Stalin refused to go along at that time and skillfully played the role of a moderate.

Break with Stalin (1925)

With Trotsky finally on the sidelines, the Zinoviev-Kamenev-Stalin triumvirate began to crumble early in 1925. The two sides spent most of the year lining up support behind the scenes. Stalin struck an alliance with Communist Party theoretician and Pravda editor Nikolai Bukharin and Soviet prime minister Alexei Rykov. Zinoviev and Kamenev allied with Lenin's widow, Nadezhda Krupskaya, and Grigory Sokolnikov, the Soviet Commissar of Finance and a non-voting Politburo member. The struggle became open at the September 1925 meeting of the Central Committee and came to a head at the XIVth Party Congress in December 1925. With only the Leningrad delegation behind them, Zinoviev and Kamenev found themselves in a tiny minority and were soundly defeated. Zinoviev was re-elected to the Politburo, but his ally Kamenev was demoted from a full member to a non-voting member and Sokolnikov was dropped altogether, while Stalin had more of his allies elected to the Politburo. Within weeks of the Congress, Stalin wrested control of the Leningrad party organization and government from Zinoviev and had him dismissed from all regional posts, leaving only the Comintern as a possible power base for Zinoviev.

With Trotsky and Kamenev against Stalin (1926–27)

During a lull in the intra-party fighting in the spring of 1926, Zinoviev, Kamenev and their supporters gravitated closer to Trotsky's supporters and the two groups soon formed an alliance, which also incorporated some smaller opposition groups within the Communist Party. The alliance became known as the United Opposition. In May 1926, Stalin, weighing his options in a letter to Vyacheslav Molotov, directed his supporters to concentrate their attacks on Zinoviev since the latter was intimately familiar with Stalin's methods from their time together in the triumvirate. Following Stalin's orders, his supporters accused Zinoviev of using the Comintern apparatus in support of factional activities (the Lashevich Affair) and Zinoviev was dismissed from the Politburo after a tumultuous Central Committee meeting in July 1926. Soon thereafter the office of the Comintern Chairman was abolished and Zinoviev lost his last important post.

Zinoviev remained in opposition to Stalin throughout 1926 and 1927, resulting in his expulsion from the Central Committee in October 1927. When the United Opposition tried to organize independent demonstrations commemorating the 10th anniversary of the Bolshevik seizure of power in November 1927, the demonstrators were dispersed by force and Zinoviev and Trotsky were expelled from the Communist Party on 12 November. Their leading supporters, from Kamenev down, were expelled in December 1927 by the XVth Party Congress, which paved the way for mass expulsions of rank and file oppositionists as well as internal exile of opposition leaders in early 1928.

Submission to Stalin (1928–34)

While Trotsky remained firm in his opposition to Stalin after his expulsion from the Party and subsequent exile, Zinoviev and Kamenev capitulated almost immediately and called on their supporters to follow suit. They wrote open letters acknowledging their mistakes and were readmitted to the Communist Party after a six-month cooling off period. They never regained their Central Committee seats, but they were given mid-level positions within the Soviet bureaucracy. Bukharin, then at the beginning of his short and ill-fated struggle with Stalin, courted Kamenev and, indirectly, Zinoviev during the summer of 1928. This was soon reported to Stalin and used against Bukharin as proof of his factionalism.

Zinoviev and Kamenev remained politically inactive until October 1932, when they were expelled from the Communist Party for failure to inform on oppositionist party members during the Ryutin Affair. Then they joined a conspiratorial bloc with Trotsky against Stalin,[12][13] together with some trotskyists who had "capitulated" to Stalin and rightists. Trotsky defined the bloc as a tool to fight stalinist repression. Pierre Broué theorized the unnamed rightists were most likely the Ryutin group itself, it was difficulty to determine, since some of Trotsky's letters were missing and were probably destroyed. The bloc most likely dissolved after 1933, when Zinoviev and Kamenev joined Stalin yet another time.[13] After again admitting their supposed mistakes, they were readmitted to the Party in December 1933. They were forced to make self-flagellating speeches at the XVIIth Party Congress in January 1934, with Stalin parading his erstwhile political opponents, now defeated and outwardly contrite.

Show trials (1935–36)

After the murder of Sergei Kirov on 1 December 1934 (which served as one of the triggers for the Great Purge of the Soviet Communist Party), Zinoviev, Kamenev and their closest associates were once again expelled from the party and arrested in December 1934. They were tried in January 1935 and were forced to admit "moral complicity" in Kirov's assassination. Zinoviev was sentenced to 10 years in prison and his supporters to various prison terms.

In August 1936, after months of careful preparations and rehearsals in secret police prisons, Zinoviev, Kamenev and 14 others, mostly Old Bolsheviks, were put on trial again. This time, the charges included forming a terrorist organization that supposedly killed Kirov and tried to kill Stalin and other leaders of the Soviet government. This Trial of the Sixteen (or the trial of the "Trotskyite-Zinovievite Terrorist Center") was the first Moscow Show Trial and set the stage for subsequent show trials where Old Bolsheviks confessed to increasingly elaborate and egregious crimes, including espionage, poisoning, and sabotage. Zinoviev and the other defendants were found guilty on 24 August 1936.

Before the trial, Zinoviev and Kamenev had agreed to plead guilty to the false charges on the condition that they not be executed, a condition that Stalin accepted, stating: "that goes without saying". Nonetheless, a few hours after their conviction, Stalin ordered their execution that night.[14] Shortly after midnight, on the morning of 25 August, Zinoviev and Kamenev were executed by shooting.

Accounts of Zinoviev's execution vary, with some having him beg and plead for his life, prompting the stoic Kamenev to tell Zinoviev to "quiet down and die with dignity." Regardless, Zinoviev put up such resistance to the guards that, instead of taking him to the appointed execution room, the guards took him into a nearby cell and shot him there.[15]

The execution of Zinoviev, Kamenev and their associates was a sensational news event in the USSR and around the world, paving the way for the mass arrests and executions of the terror of 1937–1938. In 1988, during perestroika, the Soviet government formally absolved Zinoviev and his co-defendants of the spurious charges which led to their deaths.

"Zinoviev Letter"

Zinoviev was the alleged author of the "Zinoviev Letter" which caused a sensation in the United Kingdom when published on 25 October 1924, four days before a general election. The letter called on British Communists to prepare for revolution. This document is now generally accepted to have been a fabrication, validating the declaration that Zinoviev made in a letter dated 27 October 1924:

"The letter of 15th September, 1924, which has been attributed to me, is from the first to the last word, a forgery. Let us take the heading. The organisation of which I am the president never describes itself officially as the Executive Committee of the Third Communist International; the official name is Executive Committee of the Communist International. Equally incorrect is the signature, The Chairman of the Presidium. The forger has shown himself to be very stupid in his choice of the date. On the 15th of September, 1924, I was taking a holiday in Kislovodsk, and, therefore, could not have signed any official letter....

It is not difficult to understand why some of the leaders of the Liberal-Conservative bloc had recourse to such methods as the forging of documents. Apparently they seriously thought they would be able, at the last minute before the elections, to create confusion in the ranks of those electors who sincerely sympathise with the Treaty between England and the Soviet Union. It is much more difficult to understand why the English Foreign Office, which is still under the control of the Prime Minister, MacDonald, did not refrain from making use of such a white-guardist forgery."[16]

Notes

- Russian: Григо́рий Евсе́евич Зино́вьев, IPA: [ɡrʲɪˈɡorʲɪj (j)ɪfˈsʲe(j)ɪvʲɪdʑ zʲɪˈnovʲjɪf]. Transliterated Grigorii Evseevich Zinov'ev according to the Library of Congress system.

References

- Dmitri Volkogonov, Lenin. A New Biography, translated and edited by Harold Shukman (New York: The Free Press, 1994), p. 185.

- Bennett, Gill (2006). Churchill's Man of Mystery: Desmond Morton and the World of Intelligence (Government Official History Series). UK: Routledge. pp. 118/432. ISBN 0415481686.

-

- "Letter to Bolshevik Party Members".

- "From the C.C. to Party Members & the Working Classes".

- Lenin, Vladimir. "Letter to the Congress".

- Zinoviev cynically referred to this in his eulogy of Moisei Uritsky (the chief of the Petrograd Cheka, assassinated on 30 August 1918): "When we read that in Odessa, under Skoropadsky, the rabbis assembled in special council, and there these representatives of the rich Jews, officially, before the entire world, excommunicated from the Jewish community such Jews as Trotsky and me, your obedient servant, and others – no single hair of any of us has turned gray because of grief"; Zinoviev, Sochineniia, 16:224, quoted in Bezbozhnik [The godless], no. 20 (12 September 1938).

- Leggett (1986), p. 114.

- "Baku Congress of the Peoples of the East".

- Lewis/Lih, Zinoviev and Martov: Head to Head in Halle, (2011) November Publications, London, pg117-158

- Silvio Pons and Robert Service, eds., A Dictionary of 20th-Century Communism (2010) pp 63-64, 890-892.

- Thurston, Robert W. (1996). Life and Terror in Stalin's Russia, 1934-1941. Yale University Press. ISBN 978-0-300-06401-8.

- "Pierre Broué: The "Bloc" of the Oppositions against Stalin (January 1980)". www.marxists.org. Retrieved 2020-08-06.

- Stalin: Court of the Red Tsar; Simon Sebag Montefiore, pp. 197

- Stalin: Court of the Red Tsar; Simon Sebag Montefiore, pp. 188, 193-98

- Grigorii Zinoviev, "Declaration of Zinoviev on the Alleged 'Red Plot,'" The Communist Review, vol. 5, no. 8 (Dec. 1924), pp. 365-366.

Works

- Boi za Peterburg: Dve Rechi (The Fight for St. Petersburg: Two Speeches). With Leon Trotsky. St. Petersburg: Gosudarstvennoe Izdatel'stvo, 1920.

- Leninizm: Vvedenie i izuchenie Leninizma (Leninism: Introduction to the Study of Leninism). Leningrad: Gosudarstvennoe Izdatel'stvo, 1925.

Further reading

- Corney, Frederick C. (ed.), Trotsky's Challenge: The "Literary Discussion" of 1924 and the Fight for the Bolshevik Revolution. [2016] Chicago: Haymarket Books, 2017.

- McDermott, Kevin, and Jeremy Agnew. The Comintern: a history of international communism from Lenin to Stalin (Macmillan International Higher Education, 1996).

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Grigory Zinoviev. |