Samovar

A samovar (Russian: самовар,Persian: سماور,Turkish: semaver IPA: [səmɐˈvar] (![]()

Description

Samovars are typically crafted out of plain iron, copper, polished brass, bronze, silver, gold, tin, or nickel. A typical samovar consists of a body, base and chimney, cover and steam vent, handles, tap and key, crown and ring, chimney extension and cap, drip-bowl, and teapot. The body shape can be an urn, krater, barrel, cylinder, or sphere. Sizes and designs vary, from large, "40-pail" ones holding 4 litres (1.1 US gal) to those of a modest 1 litre (0.26 US gal) size.

A traditional samovar consists of a large metal container with a tap near the bottom and a metal pipe running vertically through the middle. The pipe is filled with solid fuel which is ignited to heat the water in the surrounding container. A small (6 to 8 inch) smoke-stack is put on the top to ensure draft. After the water boils and the fire is extinguished, the smoke-stack can be removed and a teapot placed on top to be heated by the rising hot air. The teapot is used to brew a strong concentrate of tea known as заварка (zavarka). The tea is served by diluting this concentrate with кипяток (kipyatok) (boiled water) from the main container, usually at a water-to-tea ratio of 10-to-1, although tastes vary.

Prehistory

The predecessor of the modern samovar is unknown; it could have originated from Russia or Central Asia.[2][3]

Samovar-like pottery was found in Shaki, Azerbaijan in 1989. It was estimated to be at least 3,600 years old. While it differed from modern samovars in many respects, it contained the distinguishing functional feature of an inner cylindrical tube that increased the area available for heating the water. Unlike modern samovars, the tube was not closed from below, and so the device relied on an external fire (i.e. by placing it above the flame) instead of carrying its fuel and fire internally.[4]

History

The invention and cultural development of samovar in Russia was probably influenced by Byzantine and Asian cultures.[5] Conversely, Russian culture also influenced Asian, Western Europe and Byzantine cultures. Cultural connections exist to a similar Greek water-heater of classical antiquity, the autepsa, a vase with a central tube for coal. The first historically recorded samovar-makers were the Russian Lisitsyn brothers, Ivan Fyodorovich and Nazar Fyodorovich. From their childhood they were engaged in metalworking at the brass factory of their father, Fyodor Ivanovich Lisitsyn. In 1778 they made a samovar, and the same year Nazar Lisitsyn registered the first samovar-making factory in Russia. They may not have been the inventors of the samovar, but they were the first documented samovar-makers, and their various and beautiful samovar designs became very influential throughout the later history of samovar-making.[6][7] These and other early producers lived in Tula, a city known for its metalworkers and arms-makers. Since the 18th century Tula has been also the main center of Russian samovar production, with tul'sky samovar being the brand mark of the city. A Russian saying equivalent to "carrying coal to Newcastle" is "to travel to Tula with one's own samovar". Although Central Russia and Ural region were among the first Samovar producers, over time several samovar producers emerged all over Russia, which gave the somovar its different local characteristics.[8] By the 19th century samovars were already a common feature of Russian tea culture. They were produced in large numbers and exported to Central Asia and other regions. The samovar was an important attribute of Russian households and taverns to tea-drinking. It was used by all classes, from the poorest peasants up to the most well-suited people.[9][10] The Russian expression "to have a sit by the samovar" means to have a leisurely talk while drinking tea from a samovar. In everyday use samovars were an economical permanent source of hot water in older times. Various slow-burning items could be used for fuel, such as charcoal or dry pinecones. When not in use, the fire in the samovar pipe faintly smouldered. As needed it could be quickly rekindled with the help of bellows. Although a Russian jackboot сапог (sapog) could be used for this purpose, bellows were manufactured specifically for use on samovars.[11] Today samovars are popular souvenirs among tourists in Russia.[12]

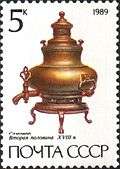

Baroque samovar, 18th century Samovars, from a 1989 series of USSR postage stamps

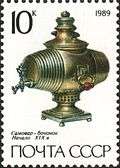

Baroque samovar, 18th century Samovars, from a 1989 series of USSR postage stamps Barrel type samovar, early 1800s, from a 1989 series of USSR postage stamps

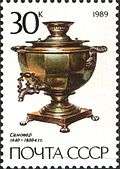

Barrel type samovar, early 1800s, from a 1989 series of USSR postage stamps "Squash" type samovar, c. 1830, from a 1989 series of USSR postage stamps

"Squash" type samovar, c. 1830, from a 1989 series of USSR postage stamps Samovar in the form of a classical vase, c. 1840, from a 1989 series of USSR postage stamps

Samovar in the form of a classical vase, c. 1840, from a 1989 series of USSR postage stamps Russian silver & enamel samovar with cup & tray, late 19th century

Russian silver & enamel samovar with cup & tray, late 19th century Samovar by Georg Stephan Dorffer, German museum

Samovar by Georg Stephan Dorffer, German museum

Samovar of old production

Samovar of old production Samovar in Tomsk museum

Samovar in Tomsk museum Samovar on table. Art by Russian painter Sergei Smirnov, made in 1981

Samovar on table. Art by Russian painter Sergei Smirnov, made in 1981

Cultural extension outside of Russia

Iran

Samovar culture has an analog in Iran and is maintained by expatriates around the world. In Iran, samovars have been used for at least two centuries (roughly since the era of close political and ethnic contact between Russia and Iran started), and electrical, oil-burning or natural gas-consuming samovars are still common. Samovar is pronounced samăvar in Persian. Iranian craftsmen used Persian art motifs in their samovar production. The Iranian city of Borujerd has been the main centre of samovar production and a few workshops still produce hand-made samovars. Borujerd's samovars are often made with German silver, in keeping with the famous Varsho-Sazi artistic style. The art samovars of Borujerd are often displayed in Iranian and Western museums as illustrations of Iranian art and handicraft.[13]

Kashmir, India

A samovar (Kashmiri: samavar) is a traditional Kashmiri kettle used to brew, boil and serve Kashmiri salted tea (Noon Chai) and kahwa. Kashmiri samovars are made of copper with engraved or embossed calligraphic motifs. In fact in Kashmir, there were two variants of samovar. The copper samovar was used by Muslims and that of brass was used by local Hindus called Kashmiri Pandit. The brass samovars were nickel-plated inside.[14] Inside a samovar there is a fire-container in which charcoal and live coals are placed. Around the fire-container there is a space for water to boil. Green tea leaves, salt, cardamom, and cinnamon are put into the water.[15]

Turkey

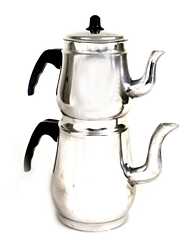

Although Turkish samovars are popular souvenirs among tourists, and charcoal burning samovars are still popular in the fields, it has in the modern homes of cities been replaced with Çaydanlık, a metal teapot with a smaller teapot on top taking the place of the cap of the lower one.

See also

References

- ЭЛЕКТРОСАМОВАР ЭСТ 3,0/1,0 - 220, Руководство по эксплуатации, Государственное унитарное предприятие "Машиностроительный завод "Штамп" им. Б.Л. ВанниковаЭ, 300004, г. Тула

- "Samovar – Russiapedia Of Russian origin". russiapedia.rt.com. Retrieved 31 August 2018.

- 1963-, Mack, Glenn Randall (2005). Food culture in Russia and Central Asia. Surina, Asele. Westport, Conn.: Greenwood Press. ISBN 978-0313327735. OCLC 57731170.CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link)

- "Birth of the Samovar?", Azerbaijan International, Autumn 2000 (8.3) Pages 42-44 (retrieved June 7, 2017)

- 1963-, Mack, Glenn Randall (2005). Food culture in Russia and Central Asia. Surina, Asele. Westport, Conn.: Greenwood Press. p. 126. ISBN 0313327734. OCLC 57731170.CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link)

- "Самовары Лисицыных (Lisitsyns Samovars)", Sloboda (in Russian), Tula, Russia

- Smith, R. E. F.; Christian, David (1984). Bread and Salt: A Social and Economic History of Food and Drink in Russia. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. p. 240. ISBN 978-0-521-25812-8.

- "History of the Tula Samovars - the Samovar and Tula are inseparable | Russian Samovar Manufacturing samovars - Coal samovars, Electric samovars, Exclusive samovars, Antique samovars". www.shopsamovar.com (in Russian). Retrieved 11 October 2018.

- "Information about Russian Samovars". www.russianamericancompany.com. Retrieved 7 September 2018.

- Barry, Mary J. "The Samovar History and Use" (PDF). fortross.org.

- Kelley, Katie (5 June 2014). "Episode 19 Russian Samovar". A History of Central Florida Podcast. Retrieved 24 January 2016.

- "Which souvenirs to buy in Russia? From Matrioskas to Cheburashka". Russiable. 28 January 2017. Retrieved 4 November 2018.

- Bandehy, Lily (2016). Tasteful memories of Persia. EBN SelfPublishing. p. 170. ISBN 978-82-92527-26-9. Retrieved 16 June 2016.

- "Original Kashmiri Samovar". Kashmir.net. 8 June 2012.

- "Kashmiri Samovar". kousa.org. 8 June 2012.

Further reading

- Israfil, Nabi (1990), Samovars: The Art of the Russian Metal Workers, Fil Caravan, ISBN 978-0-9629138-0-8.

External links

- Russian Samovar at A History of Central Florida Podcast

- Making tea with a Samavar at RussianTeaCake.com