Russian icons

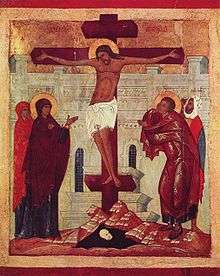

The use and making of icons entered Kievan Rus' following its conversion to Orthodox Christianity in AD 988. As a general rule, these icons strictly followed models and formulas hallowed by Byzantine art, led from the capital in Constantinople. As time passed, the Russians widened the vocabulary of types and styles far beyond anything found elsewhere in the Orthodox world.

The personal, innovative and creative traditions of Western European religious art were largely lacking in Russia before the 17th century, when Russian icon painting became strongly influenced by religious paintings and engravings from both Protestant and Catholic Europe. In the mid-17th-century changes in liturgy and practice instituted by Patriarch Nikon resulted in a split in the Russian Orthodox Church. The traditionalists, the persecuted "Old Ritualists" or "Old Believers", continued the traditional stylization of icons, while the State Church modified its practice. From that time icons began to be painted not only in the traditional stylized and non-realistic mode, but also in a mixture of Russian stylization and Western European realism, and in a Western European manner very much like that of Catholic religious art of the time. These types of icons, while found in Russian Orthodox churches, are also sometimes found in various sui juris rites of the Catholic Church.

Russian icons are typically paintings on wood, often small, though some in churches and monasteries may be much larger. Some Russian icons were made of copper.[1] Many religious homes in Russia have icons hanging on the wall in the krasny ugol, the "red" or "beautiful" corner.

There is a rich history and elaborate religious symbolism associated with icons. In Russian churches, the nave is typically separated from the sanctuary by an iconostasis (Russian ikonostas, иконостас), or icon-screen, a wall of icons with double doors in the centre.

Russians sometimes speak of an icon as having been "written", because in the Russian language (like Greek, but unlike English) the same word (pisat', писать in Russian) means both to paint and to write. Icons are considered to be the Gospel in paint, and therefore careful attention is paid to ensure that the Gospel is faithfully and accurately conveyed.

Icons considered miraculous were said to "appear." The "appearance" (Russian: yavlenie, явление) of an icon is its supposedly miraculous discovery. "A true icon is one that has 'appeared', a gift from above, one opening the way to the Prototype and able to perform miracles".[2]

History

Some of the most venerated but whole icons considered to be products of miraculous thaumaturge are those known by the name of the town associated with them, such as the Vladimir, the Smolensk, the Kazan and the Częstochowa images, all of the Virgin Mary, usually referred to by Orthodox Christians as the Theotokos, the Birth-Giver of God.

The preeminent Russian icon painter was Andrei Rublev (1360 – early 15th century), who was "glorified" (officially recognized as a saint) by the Moscow Patriarchate in 1988. His most famous work is The Old Testament Trinity.

Russians often commissioned icons for private use, adding figures of specific saints for whom they or members of their family were named gathered around the icon's central figure. Icons were frequently clad in metal covers (the oklad оклад, or more traditionally, riza риза, meaning "robe") of gilt or silvered metal of ornate workmanship, which were sometimes enameled, filigreed, or set with artificial, semiprecious or even precious stones and pearls. Pairs of icons of Jesus and Mary were given as wedding presents to newly married couples.

There are far more varieties of icons of the Virgin Mary in Russian icon painting and religious use than of any other figure; Marian icons are commonly copies of images considered to be miraculous, of which there are hundreds: "The icons of Mary were always deemed miraculous, those of her son rarely so".[3] Icons of Mary most often depict her with the child Jesus in her arms; some, such as the "Kaluga", "Fiery-Faced" "Gerondissa", "Bogoliubovo", "Vilna", "Melter of Hard Hearts", "Seven Swords", etc., along with icons that depict events in Mary's life before she gave birth to Jesus such as the Annunciation or Mary's own birth, omit the child.

Because icons in Orthodoxy must follow traditional standards and are essentially copies, Orthodoxy never developed the reputation of the individual artist as Western Christianity did, and the names of even the finest icon painters are seldom recognized except by some Eastern Orthodox or art historians. Icon painting was and is a conservative art, in many cases considered a craft, in which the painter is essentially merely a tool for replication. The painter did not seek individual glory but considered himself a humble servant of God. That is why in the 19th and early 20th centuries, icon painting in Russia went into a great decline with the arrival of machine lithography on paper and tin, which could produce icons in great quantity and much more cheaply than the workshops of painters. Even today large numbers of paper icons are purchased by Orthodox rather than more expensive painted panels.

As the painter did not intend to glorify himself, it was not deemed necessary to sign an icon. Later icons were often the work of many hands, not of a single artisan. Nonetheless some later icons are signed with name of the painter, as well as the date and place. A peculiarity of dates written on icons is that many are dated from the "Creation of the World", which in Eastern Orthodoxy was believed to have taken place on September 1 in the year 5,509 before the birth of Jesus.

During the Soviet era in Russia, former village icon painters in Palekh, Mstyora, and Kholuy transferred their techniques to laquerware, which they decorated with ornate depictions of Russian fairy tales and other non-religious scenes. This transition from religious to secular subjects gave rise, in the mid-1920, to Russian lacquer art on papier-mâché. Most distinguished within this relatively new art form are the intricate Palekh miniature paintings on a black lacquer background.

Many Russian icons were destroyed, or sold abroad, by agents of the Soviet government; some were hidden to avoid destruction, or were smuggled out of the country. Since the fall of communism, numbers of icon painting studios have again opened and are painting in a variety of styles for the local and international market. Many older, hidden icons have also been retrieved from hiding, or brought back from overseas.

In the late 19th and early 20th centuries, the market for icons expanded beyond Orthodox believers to include those collecting them as examples of Russian traditional art and culture. The same period witnessed much forgery of icons painted in the Pre-Nikonian manner. Such fakes, often beautifully done, were artificially aged through skillful techniques and sold as authentic to Old Believers and collectors. Some still turn up on the market today, along with numbers of newly painted intentional forgeries, as well as icons sold legitimately as new but painted in earlier styles. Many icons sold today retain some characteristics of earlier painting but are nonetheless obviously contemporary.

Painting techniques and collecting

Most Russian icons are painted using egg tempera on specially prepared wooden panels, or on cloth glued onto wooden panels. Gold leaf is frequently used for halos and background areas; however, in some icons, silver leaf, sometimes tinted with shellac to look like gold,[4] is used instead, and some icons have no gilding at all. Russian icons may also incorporate elaborate tin, bronze or silver exterior facades that are usually highly embellished and often multi-dimensional. These facades are called rizas or oklads.

A regular aspect of icon painting is to varnish over the image with drying oil, either immediately after the paint is dry, or later on. The majority of hand-painted Russian icons exhibit some degree of surface varnish, although many do not.

Panels that utilize what are known as "back slats" — cross members that are dovetailed into the back of the boards that make up the panel to prevent warping during the drying process and to ensure structural integrity over time — are usually older than 1880/1890. Subsequent to 1880/1890, advances in materials negated the need for these cross members, thus, are seen either on icons painted after this time period when the intent of the artist was to deceive by creating an "older looking" icon, or on icons which are rendered according to traditional means as a way of honoring the old processes. Back slats are sometimes necessary on newer icons of large size for the same reasons (warping and stability) as existed pre-1900.

Age, authenticity, and forgeries

Since the 1990s, numerous late 19th- and early 20th-century icons have been artificially aged, then purported to unwitting buyers and collectors as being older than they really are. Often these "semi-forgeries" are perpetrated by master-level Russian icon painters, highly skilled in their ability to not only paint extraordinary works of art, but to "create age" on the finished icon. While the resulting icon may very well be a fine work of art that many would be glad to own, it is still considered to be a work of deception, thus lacking value as an icon beyond its decorative qualities.

Another problem area in the field of icon collecting is the "recomposing" of legitimately old icons with newly painted then falsely aged images that exhibit a higher degree of artistry. For example, a primitive or "folk art" icon from the 17th or 18th century might be repainted by a modern master painter, then the image falsely aged to match the panel in order to create an icon that could pass as a 17th- or 18th-century masterwork. In reality, it is nothing more than a 20th- or 21st-century masterwork on a 17th- or 18th-century panel. With the rise in the values and prices of authentic icons in recent decades, this is now also done with lower quality 19th-century folk icons that are repainted by contemporary masters and then artificially aged to appear to match the age of the panel.

Legalities

Pursuant to Russian law, it is presently illegal to export any Russian icon that is over one hundred years in age. Any and all icons being exported from Russia must be accompanied by a certificate from the Ministry of Culture of the Russian Federation, attesting to the age of the icon. While Russian law regarding the exportation of icons is quite clear, examples of Russian icons over 100 years of age are regularly introduced into the open market by way of smuggling into the neighboring Baltic countries, or as a result of corrupt Ministry of Culture officials who are willing to certify an otherwise unexportable icon as being "100 years old" in order to facilitate its transfer.

Since the collapse of the Soviet Union, many Russian icons have been repatriated via direct purchase by Russian museums, private Russian collectors, or as was the case of Pope John Paul II giving an 18th-century copy of the famous Our Lady of Kazan icon to the Russian Orthodox Church, returned to Russia in good faith.[5]

The founder of the company Ikonen Mautner, Mr. Erich Mautner, received export approvals for antique icons in the early 1960s from the Russian government. During the following years, based in Vienna, Austria, Mr. Mautner developed an extensive icon trade in worldwide. Collectors and traders from all over the world came flocking, to acquire some copies of these rarity treasures. Every piece of these splendid icons was examined by the icon expert of the Vienna Dorotheum and was provided with a certificate.

Notes

- Ahlborn, Richard E. and Vera Beaver-Bricken Espinola, eds. Russian Copper Icons and Crosses From the Kunz Collection: Castings of Faith. Washington, DC: Smithsonian Institution Press. 1991. 85 pages with illustrations, some colored. Includes bibliographical references pages 84-85. Smithsonian Studies in History and Technology: No. 51.

- Father Vladimir Ivanov (1988). Russian Icons. Rizzoli Publications.

- Hubbs, Joanna (1993). Mother Russia: the Feminine Myth in Russian Culture. Indiana University Press. ISBN 0-253-33860-3.

- Espinola, Vera Beaver-Bracken (1992). "Russian Icons: Spiritual And Material Aspects". Journal of the American Institute for Conservation. The American Institute for Conservation of Historic &. 31 (1): 17–22. doi:10.2307/3179608. JSTOR 3179608.

- "The handover of the icon of Kazan is an historic event". AsiaNews.it. August 26, 2004. Archived from the original on June 19, 2006.

Books

- Behold the Beauty of the Lord: Praying with Icons by Henri J. M. Nouwen, from Ave Maria Press

- Hidden and Triumphant: The Underground Struggle to Save Russian Iconography, by Irina Yazykova, Paraclete Press, 2010.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to icons of Russia. |

- Ikonen Mautner - One of the most extensive collections of Russian Icons from the 17th, 18th and 19th century outside of Russia.

- Old Russian Icons - The Russian Art Gallery.

- Museum of Russian Icons - Museum of Russian Icons Clinton, MA.

.jpg)