Yellow-tailed black cockatoo

The yellow-tailed black cockatoo (Zanda funerea) is a large cockatoo native to the south-east of Australia measuring 55–65 cm (22–26 in) in length. It has a short crest on the top of its head. Its plumage is mostly brownish black and it has prominent yellow cheek patches and a yellow tail band. The body feathers are edged with yellow giving a scalloped appearance. The adult male has a black beak and pinkish-red eye-rings, and the female has a bone-coloured beak and grey eye-rings. In flight, yellow-tailed black cockatoos flap deeply and slowly, with a peculiar heavy fluid motion. Their loud, wailing calls carry for long distances.

| Yellow-tailed black cockatoo | |

|---|---|

_-Wamboin-8.jpg) | |

| A male in Wamboin, NSW, Australia | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Aves |

| Order: | Psittaciformes |

| Family: | Cacatuidae |

| Genus: | Zanda |

| Species: | Z. funerea |

| Binomial name | |

| Zanda funerea Shaw, 1794 | |

| Subspecies | |

|

Z. f. funerea | |

| |

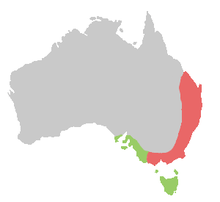

| Yellow-tailed black cockatoo range:[3] Z. f. funerea in red Z. f. xanthanota in green | |

The yellow-tailed black cockatoo is found in forested regions from south and central eastern Queensland to southeastern South Australia including a very small population persisting in the Eyre Peninsula. Two subspecies are recognised, although Tasmanian and southern mainland populations of the southern subspecies xanthanotus may be distinct enough from each other to bring the total to three. Birds of subspecies funereus (Queensland to eastern Victoria) have longer wings and tails and darker plumage overall, while those of xanthanotus (western Victoria, South Australia and Tasmania) have more prominent scalloping.

Unlike other cockatoos, a large proportion of the yellow-tailed black cockatoo's diet is made up of wood-boring grubs; they also eat seeds. They nest in hollows high in trees with fairly large diameters, generally Eucalyptus. Although they remain common throughout much of their range, fragmentation of habitat and loss of large trees suitable for nesting has caused population decline in Victoria and South Australia. In some places yellow-tailed black cockatoos appear to have partially adapted to recent human alteration of landscape and they can often be seen in parts of urban Canberra, Sydney, Adelaide and Melbourne. The species is not commonly seen in aviculture, especially outside Australia. Like most parrots, it is protected by CITES, an international agreement that makes trade, export, and import of listed wild-caught species illegal.

Taxonomy and naming

The yellow-tailed black cockatoo was first described in 1794 by the English naturalist George Shaw as Psittacus funereus, its specific name funereus relating to its dark and sombre plumage, as if dressed for a funeral.[4] The French zoologist Anselme Gaëtan Desmarest reclassified it in the new genus Calyptorhynchus in 1826.[5]

The ornithologist John Gould knew the bird as the funereal cockatoo.[6] "Yellow-tailed black cockatoo" has been designated the official name by the International Ornithologists' Union (IOC).[7] Other common names used include yellow-eared black cockatoo, and wylah.[4] Wy-la was an aboriginal term from the Hunter Region of New South Wales,[6] while the Dharawal name from the Illawarra region is Ngaoaraa.[8] Scientist and cockatoo authority Matt Cameron has proposed dropping the "black" and shortening the name to "yellow-tailed cockatoo", explaining that shorter names are more widely accepted.[9]

Within the genus, the yellow-tailed and the two Western Australian white-tailed species, the short-billed and long-billed black cockatoos, form the genus Zanda. The red-tailed and glossy black cockatoos form the other genus, Calyptorhynchus. The two groups are distinguished by their juvenile food begging calls and the degree of sexual dimorphism: males and females of the latter group have markedly different plumage, whereas those of the former have similar plumage.[10]

The three species of the genus Zanda have been variously considered as two, then as a single species for many years. In a 1979 paper, Australian ornithologist Denis Saunders highlighted the similarity between the short-billed and the southern race xanthanota of the yellow-tailed and treated them as a single species, with the long-billed as a distinct species. He proposed that Western Australia had been colonised on two separate occasions, once by a common ancestor of all three forms (which became the long-billed black cockatoo), and later by what has become the short-billed black cockatoo.[11] However, an analysis of protein allozymes published in 1984 revealed the two Western Australian forms to be more closely related to each other than to the yellow-tailed,[12] and the consensus since then has been to treat them as three separate species.[10]

Within the species, two subspecies are recognised:

- Z. f. funerea, the nominate form, is known as the eastern yellow-tailed black cockatoo. It is found from the Berserker Range in Central Queensland, south through New South Wales, and into eastern Victoria. It is distinguished by its overall larger size, longer tail and wings, and larger bill and claws.[4][11]

- Z. f. xanthanota, known as the southern yellow-tailed black cockatoo, is found in western Victoria, southeastern South Australia, the islands of Bass Strait, and Tasmania. Gould described it in 1838 and later changed his spelling to "xanthonotus". However, the first name was recognised as taking precedence under ICZN naming rules and its spelling preserved.[13] Saunders reported in 1979 that male birds from Tasmania had wider bills than their mainland relatives, and that Tasmanian female birds were larger than males.[11] However, this observation has yet to be replicated and most authorities only recognise two subspecies. If a third subspecies is recognised, the southern mainland subspecies would be named whiteae, having been named so by Gregory Mathews in 1912, and the name xanthanotus, originally applied to a Tasmanian specimen, would be restricted to the Tasmanian population.[14]

Description

The yellow-tailed black cockatoo is 55–65 cm (22–26 in) in length and 750–900 grams in weight.[3] It has a short mobile crest on the top of its head, and the plumage is mostly brownish-black with paler feather-margins in the neck, nape, and wings, and pale yellow bands in the tail feathers.[3] The tails of birds of subspecies funereus measure around 33 cm (13 in), with an average tail length 5 cm (2.0 in) longer than xanthanotus. Male funereus birds weigh on average around 731 g (1.612 lb) and females weigh about 800 g (1.8 lb).[14] Birds of the xanthanotus race on the mainland average heavier than the Tasmanian birds; the males on the mainland weigh on average around 630 g and females 637 g (1.404 lb), while those on Tasmania average 583 and 585 g (1.290 lb) respectively.[14] Both mainland and Tasmanian birds of the xanthanotus race average about 28 cm (11 in) in tail length.[14] The plumage is a more solid brown-black in the eastern subspecies,[14] while the southern race has more pronounced yellow scalloping on the underparts.[4][11]

The male yellow-tailed black cockatoo has a black bill, a dull yellow patch behind each eye, and pinkish or reddish eye-rings. The female has grey eye-rings, a horn-coloured bill, and brighter and more clearly defined yellow cheek-patches.[3] Immature birds have duller plumage overall, a horn-coloured bill, and grey eye-rings;[3][15] The upper beak of the immature male darkens to black by two years of age, commencing at the base of the bill and spreading over ten weeks. The lower beak blackens later by four years of age.[16] The elongated bill has a pointed maxilla (upper beak), suited to digging out grubs from tree branches and trunks.[17] Records of the timing of the eye ring changing from grey to pink in male birds are sparse, but have been recorded anywhere from one to four years of age.[16] Australian farmer and amateur ornithologist John Courtney proposed that the similarity between juvenile and female eye rings prevented adult males becoming aggressive to younger birds. He also observed the eye rings to flush brighter in aggressive males.[18] Moulting appears to take place in stages over the course of a year, and is poorly understood.[16]

The yellow-tailed black cockatoo is distinguished from other dark-plumaged birds by its yellow tail and ear markings, and its contact call.[4] Parts of its range overlap with the ranges of two cockatoo species that have red tail banding, the red-tailed cockatoo and the glossy black cockatoo.[19] Crow species may appear similar when seen flying at a distance; however, crows have shorter tails, a quicker wing beat, and different calls.[20]

An all-yellow bird lacking black pigment was recorded in Wauchope, New South Wales, in December 1996, and it remained part of the local group of cockatoos for four years. Birds with part-yellow plumage have been recorded from different areas in Victoria.[21]

Distribution and habitat

The yellow-tailed black cockatoo is found up to 2,000 m (6,600 ft) above sea level over southeastern Australia including the island of Tasmania and the islands of the Bass Strait (King, Flinders, Cape Barren islands), and also on Kangaroo Island.[20] On Tasmania and the islands of the Bass Strait it is the only native black-coloured cockatoo.[20] On the mainland, it is found from the vicinity of Gin Gin and Gympie in south and central eastern Queensland, south through New South Wales, where it occurs along the Great Dividing Range and to the coast, and into and across most of Victoria bar the northern and northwestern corner, to the Coorong and Mount Lofty Ranges in southeastern South Australia.[15] A tiny population numbering 30 to 40 birds inhabits the Eyre Peninsula. There they are found in sugar gum (Eucalyptus cladocalyx) woodland in the lower peninsula and migrate to the mallee areas in the northern peninsula after breeding.[22] There is evidence that birds on the New South Wales south coast move from elevated areas to lower lying areas towards the coast in winter. They are generally common or locally very common in a wide range of habits, although they tend to be locally rare at the limits of their range.[20] Their breeding range is restricted to areas with large old trees.[20]

The birds may be found in a variety of habitats including grassy woodland, riparian forest, heathland, subalpine areas, pine plantations, and occasionally in urban areas, as long as there is a plentiful food supply.[23] They have also spread to parts of suburban Sydney, particularly on or near golf courses, pine plantations and parks,[24] such as Centennial Park in the eastern suburbs.[25] It is unclear whether this is adaptive or because of loss of habitat elsewhere.[24] In urban Melbourne, they have been recorded at Yarra Bend Park.[26] The "Black Saturday bushfires" of 2009 appear to have caused sufficient loss of their natural habitat for them to have been sighted in other parts of the urban areas of Melbourne as well.

Ecology and behaviour

Yellow-tailed black cockatoos are diurnal, raucous and noisy, and are often heard before being seen.[20] They make long journeys by flying at a considerable height while calling to each other, and they are often seen flying high overhead in pairs, or trios comprising a pair and their young, or small groups.[20][27] Outside of the breeding season in autumn or winter they may coalesce into flocks of a hundred birds or more, while family interactions between pairs or trios are maintained.[20] They are generally wary birds, although they can be less shy in urban and suburban areas.[20] They generally keep to trees, only coming to ground level to inspect fallen pine or Banksia cones or to drink. Flight is fluid and has been described as "lazy", with deep, slow wingbeats.[27]

Tall eucalypts that are emergent over other trees in wooded areas are selected for roosting sites. It is here that the cockatoos rest for the night,[28] and also rest to shelter from the heat of the day.[20] They often socialise before dusk, engaging in preening, feeding young, and flying acrobatically. Flocks will return to roost earlier in bad weather.[28]

The usual call is a high-pitched wailing contact call, kee-ow … kee-ow … kee-ow, made while flying or roosting,[29] and can be heard from afar.[20][25] Birds may also make a harsh screeching alarm call.[20] They also make a soft, chuckling call when searching for cossid moth larvae.[29] Adults are normally quiet when feeding, while juveniles make frequent noisy begging calls.[4] The superb lyrebird can mimic the adult yellow-tailed black cockatoo's contact call with some success.[30]

Breeding

The breeding season varies according to latitude, taking place from April to July in Queensland, January to May in northern New South Wales, December to February in southern New South Wales, and October to February in Victoria, South Australia and Tasmania.[31] The male yellow-tailed black cockatoo courts by puffing up his crest and spreading his tail feathers to display his yellow plumage. Softly growling, he approaches the female and bows to her three or four times.[29] His eye ring may also flush a deeper pink.[18] Nesting takes place in large vertical tree hollows of tall trees, generally eucalypts, which may be living or dead.[31] Isolated trees are generally chosen, so birds can fly to and from them relatively unhindered. The same tree may be used for many years.[32] A 1994 study of nesting sites in Eucalyptus regnans forest in the Strzelecki Ranges in eastern Victoria found the average age of trees used for hollows by the yellow-tailed black cockatoo to be 228 years. The authors noted that the proposed 80–150 year rotation time for managed forests would impact on the numbers of suitable trees.[33]

Hollows can be 1 to 2 metres (3.3 to 6.6 ft) deep and 0.25–0.5 metres (9.8–19.7 in) wide, with a base of woodchips.[32] A chance felling of a eucalypt known to have been used as a nesting tree near Scottsdale in northeastern Tasmania allowed accurate measurements to be made, yielding a hollow measuring 56 cm (22 in) high by 30 cm (12 in) wide at the mouth, and at least 65 cm (26 in) deep, in a tree which measured 72 cm (28 in) in diameter below the hollow.[34] Both the male and female prepare the hollow for breeding,[28] which involves peeling or scraping off wood shavings from the inside the hollow to prepare bedding for the eggs. Gum leaves are occasionally added as well.[31] The clutch consists of one or two white lustreless rounded oval eggs which may have the occasional lime nodule. The first egg averages around 47 or 48 mm long and 37 mm in diameter (2 × 1.4 in). The second egg is around 2 mm smaller all over and is laid two to seven days later. The female incubates the eggs alone and begins after the completion of laying. She enters the hollow feet first, and is visited by the male who brings food two to four times a day.[31] Later both parents help to raise the chicks.[3] The second chick is neglected and usually perishes in infancy.[35] Information on the breeding of birds in the wild is lacking; however, the incubation period in captivity is 28–31 days.[36] Newly hatched chicks are covered with yellow down and have pink beaks that fade to a greyish white by the time of fledging.[16][37] Chicks fledge from the nest three months after hatching,[36] and remain in the company of their parents until the next breeding season.[28]

Like other cockatoos, this species is long-lived. A pair of yellow-tailed black cockatoos at Rotterdam Zoo stopped breeding when they were 41 and 37 years of age, but still showed signs of close bonding.[38] Birds appear to reach sexual maturity between four and six years of age; this is the age range of breeding recorded in captivity.[28]

Feeding

The diet of the yellow-tailed black cockatoo is varied and available from a range of habitats within its distribution, which reduces their vulnerability to degradation or change in habitat.[39] Much of the diet comprises seeds of native trees, particularly she-oaks (Allocasuarina and Casuarina, including A. torulosa and A. verticillata), but also Eucalyptus (including E. maculata flowers and E. nitida seeds), Acacia (including gum exudate and galls), Banksia (including the green seed pods and seeds of B. serrata, B. integrifolia, and B. marginata), and Hakea species (including H. gibbosa, H. rugosa, H. nodosa, H. sericea, H. cycloptera, and H. dactyloides). They are also partial to pine cones in plantations of the introduced Pinus radiata and to other introduced trees, including Cupressus torulosa, Betula pendula and the buds of elm Ulmus species.[40][41] In the Eyre Peninsula, the yellow-tailed black cockatoo has become dependent on the introduced Aleppo pine (Pinus halepensis), alongside native species.[42]

The yellow-tailed black cockatoo is very fond of the larvae of tree-boring beetles, such as the longhorn beetle Tryphocaria acanthocera, and cossid moth Xyleutes boisduvali.[40][41] Birds seek them all year but especially in June and July, when the moth caterpillars are largest, and they are accompanied by their just fledged young. They search out holes and make exploratory bites looking for larvae. If successful, they peel and tear down a strip of bark to make a perch for themselves before continuing to gouge and excavate the larvae, which have deeply tunneled into the heartwood.[43]

A yellow-tailed black cockatoo was observed stripping 4 cm × 2 cm (1.57 in × 0.79 in) pieces of bark off the trunk of a dead Leptospermum tree in Acacia melanoxylon swamp near Togari in northwestern Tasmania. It then scraped a layer of white material about 0.5 mm thick from the inner surface with its beak. This white layer turned out to be hyphomycete fungi and slime mould that grew in the cambium of the bark.[44]

Yellow-tailed black cockatoos have been reported flocking to Banksia cones ten days after bushfire as the follicles open. With pine trees, they prefer green cones, nipping them off at the stem and holding in one foot, then systematically lifting each segment and extracting the seed. A cockatoo spends about twenty minutes on each pine cone.[45]

They drink at various places, from stock troughs to puddles, and do so in the early morning or late in the afternoon. Insect larvae and Fabaceae seeds are among food reported to have been fed to young.[40]

Parasites

In 2004, a captive yellow-tailed black cockatoo and two free-living tawny frogmouths (Podargus strigoides) suffering neurological symptoms were shown to be hosting the rat nematode Angiostrongylus cantonensis. They were the first non-mammalian hosts discovered for the organism.[46] A species of feather mite, Psittophagus calyptorhynchi, has also been isolated from the yellow-tailed black cockatoo, its only host to date.[47]

Relationship with humans

Yellow-tailed black cockatoos can cause damage in pine and Eucalyptus plantations by weakening stems through gouging out pieces of wood to extract moth larvae. In places with these gum plantations, the population of the larva of the cossid moth Xyleutes boisduvali grows, which then leads to increased predation (and hence tree damage) by cockatoos. Furthermore, plantations generally lack undergrowth which might have prevented cockatoos from damaging younger trees.[43] Yellow-tailed black cockatoos were shot as pests in some districts of New South Wales until the 1940s for this reason.[24] The yellow-tailed black cockatoo is promoted by the Shoalhaven City Council local government on the NSW south coast as the region's bird. Within the Jervis Bay area the birds can be seen feasting on the many Casuarina trees native to the area.

Although it is classified as least concern on the IUCN Red List of Threatened Species,[1] and not listed nationally as threatened, the yellow-tailed black cockatoo is declining in numbers in Victoria and South Australia. This is due to habitat fragmentation and loss of large trees used for breeding hollows, although birds have become more plentiful in the vicinity of pine plantations.[48] It is listed as vulnerable in South Australia, due to its decline in the Adelaide and Mount Lofty Ranges,[49] and particularly the perilous status of the small isolated population on the Eyre Peninsula, which has declined sharply since European settlement, probably from loss of suitable habitat.[42] A recovery program was commenced in 1998. Efforts to increase the population include fencing off remnants of native bushland, planting food plants such as Hakea rugosa, monitoring breeding, and raising chicks in captivity.[50] As a result, the population has increased from a low of 19–21 individuals in 1998.[50]

This species was seldom seen in captivity before the late 1950s, after which time a large number of wild-caught birds entered the Australian market. Since then, it has become more common, but is still rarely seen outside Australia. Captive yellow-tailed black cockatoos require a large aviary to avoid apathy and poor health.[51] There is some evidence that protein may be more important to them than to other cockatoos, and low protein has been linked with the production of yolkless eggs in captivity. Females in particular enjoy mealworms.[52] They can be placid and tolerate sharing an enclosure with smaller parrots, but do not handle disturbance while breeding.[53] As with other black cockatoos, yellow-tailed black cockatoos are rarely seen in European zoos, since Australia restricted exportation of wildlife in 1959, but birds seized by government agencies in Germany, the Netherlands and the United Kingdom have been loaned to zoos that are members of the European Association of Zoos and Aquaria (EAZA). In 2000, there were pairs of yellow-tailed black cockatoos in Puerto de la Cruz's Loro Parque zoo in Spain and in Rotterdam.[52] Like most species of parrot, the yellow-tailed black cockatoo is protected by the Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species of Wild Fauna and Flora (CITES) with its placement on the Appendix II list of vulnerable species, which makes the import, export, and trade of listed wild-caught animals illegal.[54][55]

References

- BirdLife International (2012). "Zanda funerea". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. 2012. Retrieved 26 November 2013.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- See text – this is the name given to birds of South Australia and Western Victoria if Tasmanian and southern mainland birds are considered separate subspecies. This division is not generally accepted.

- Forshaw (2006), plate 1.

- Higgins, p. 66.

- Desmarest, Anselme Gaëtan (1826). "[Parrots]". Dictionnaire des Sciences Naturelles dans lequel on traite méthodiquement des différens êtres de la nature ... [Dictionary of Natural Sciences, where all natural beings are treated methodically ...] (in French). 39 (PEROQ–PHOQ). Strasbourg: F.G. Levrault. pp. 21, 117. OCLC 4345179.

- "Indigenous Bird Names of the Hunter Region of New South Wales". Australian Museum website. Sydney, New South Wales: Australian Museum. 2009. Archived from the original on 17 October 2009. Retrieved 22 February 2010.

- Gill, Frank; Donsker, David, eds. (2019). "Parrots, cockatoos". World Bird List Version 9.2. International Ornithologists' Union. Retrieved 2 July 2019.

- Wesson, Sue (August 2005). "Murni Dhugang Jirrar: Living in the Illawarra" (PDF). Department of Environment, Climate Change, and Water. Department of Environment, Climate Change, and Water, State Government of New South Wales. p. 67. Archived from the original (PDF) on 21 June 2018. Retrieved 22 February 2010.

- Cameron, p. 7.

- Christidis, Les; Boles, Walter E. (2008). Systematics and Taxonomy of Australian Birds. Canberra: CSIRO Publishing. pp. 150–51. ISBN 978-0-643-06511-6.

- Saunders, D. A. (1979). "Distribution and taxonomy of the White-tailed and Yellow-tailed Black-Cockatoos Calyptorhynchus spp". Emu. 79 (4): 215–27. doi:10.1071/MU9790215.

- Adams, M.; Baverstock, P. R.; Saunders, D. A.; Schodde, R.; Smith, G. T. (1984). "Biochemical systematics of the Australian cockatoos (Psittaciformes: Cacatuinae)". Australian Journal of Zoology. 32 (3): 363–77. doi:10.1071/ZO9840363.

- "Subspecies Calyptorhynchus (Zanda) funereus xanthanotus Gould, 1838". Australian Biological Resources Study: Australian Faunal Directory. Canberra, ACT: Department of the Environment, Water, Heritage and the Arts, Commonwealth of Australia. 20 November 2008. Archived from the original on 21 September 2011. Retrieved 13 March 2010.

- Higgins, p. 76.

- Lendon, p. 57.

- Higgins, p. 75.

- Cameron, p. 65.

- Courtney, J. (1986). "Age-related colour changes and behaviour in the northern Funereal Black-Cockatoo Calyptorhynchus funereus funereus". Australian Bird Watcher. 11: 137–45.

- "Bird Finder: Yellow-tailed Black-Cockatoo". Australian Museum website. Sydney, New South Wales: Australian Museum. 22 December 2006. Retrieved 13 March 2010.

- Forshaw (2006), p. 18.

- Forshaw (2002), p. 70.

- Cameron, p. 19.

- Cameron, p. 76.

- Higgins, p. 68.

- Waller, Trevor (3 June 2009). "Yellow-tailed Black Cockatoo". Centennial Parklands. Centennial Park and Moore Park Trust. Archived from the original on 10 October 2009. Retrieved 4 March 2010.

- "Melbourne Parks and Gardens". Melbourne Information. Australian Tourist Information Centres. 2010. Archived from the original on 21 February 2010. Retrieved 4 March 2010.

- Forshaw (2002), p. 63.

- Higgins, p. 71.

- Higgins, p. 72.

- Zann, Richard; Dunstan, Emily (2008). "Mimetic song in superb lyrebirds: species mimicked and mimetic accuracy in different populations and age classes". Animal Behaviour. 76 (3): 1043–54. doi:10.1016/j.anbehav.2008.05.021.

- Higgins, p. 73.

- Beruldsen, Gordon (2003). Australian Birds: Their Nests and Eggs. Kenmore Hills: G. Beruldsen. p. 241. ISBN 0-646-42798-9.

- Nelson, J. L.; Morris, B. J. (1994). "Nesting requirements of the Yellow-tailed Black-Cockatoo, Calyptorhynchus funereus, in Eucalyptus regnans forest, and implications for forest management". Wildlife Research. 21 (3): 267–78. doi:10.1071/WR9940267.

- Wapstra, Mark; Doran, Niall (2004). "Observations on a nesting hollow of Yellow-tailed Black Cockatoo, and the felled tree that hosted it, in northeastern Tasmania" (PDF). Tasmanian Naturalist. 126: 59–63. Archived from the original (PDF) on 29 September 2009. Retrieved 5 March 2010.

- Lendon, p. 59.

- Cameron, p. 140.

- Higgins, p. 74.

- Brouwer, K.; Jones, M. L.; King, C. E.; Schifter, H. (2000). "Longevity records for Psittaciformes in captivity". International Zoo Yearbook. 37: 299–316. doi:10.1111/j.1748-1090.2000.tb00735.x.

- Cameron, p. 74.

- Higgins, p. 70.

- Barker, R. D.; Vestjens, W. J. M. (1984). The Food of Australian Birds: (I) Non-passerines. Melbourne University Press. pp. 330–31. ISBN 0-643-05007-8.

- van Weenen, Jason (17 August 2009). "Threatened Species – Yellow-tailed Black-Cockatoo: Critically Endangered Eyre Peninsula Yellow-tailed Black-Cockatoos". Department for Environment and Heritage – Biodiversity. Department for Environment and Heritage, South Australian Government. Archived from the original on 25 October 2009. Retrieved 22 February 2010.

- Mcinnes, R. S.; Carne, P. B. (1978). "Predation of cossid moth larvae by Yellow-tailed Black Cockatoos causing losses in plantations of Eucalyptus grandis in north coastal New South Wales". Australian Wildlife Research. 5 (1): 101–21. doi:10.1071/WR9780101.

- Taylor, R. J.; Mooney, N. J. (1990). "Fungal feeding by yellow-tailed black cockatoo" (PDF). Corella. 14 (1): 30. Archived from the original (PDF) on 17 April 2019.

- Dawson, Jill (1994). The Yellow-tailed Black Cockatoo, Calyptorhynchus funereus funereus and Calyptorhynchus funereus xanthanotus : Report on the Yellow-tailed Black Cockatoo Survey, 1983–1988. 1. Nunawading, Victoria: Bird Observers Club of Australia. pp. 7–8. ISBN 0-909711-19-4.

- Monks, Deborah J.; Carlisle, Melissa S.; Carrigan, Mark; et al. (December 2005). "Angiostrongylus cantonensis as a cause of cerebrospinal disease in a yellow-tailed black cockatoo (Calyptorhynchus funereus) and two tawny frogmouths (Podargus strigoides)". Journal of Avian Medicine and Surgery. 19 (4): 289–93. doi:10.1647/2004-024.1.

- Mironov, S. V.; Dabert, J.; Ehrnsberger, R. (2003). "A review of feather mites of the Psittophagus generic group (Astigmata, Pterolichidae) with descriptions of new taxa from parrots (Aves, Psittaciformes) of the Old World". Acta Parasitologica. 48 (4): 280–93.

- Higgins, p. 67.

- Biodiversity Conservation Unit; Adelaide Region (May 2008). "Adelaide and Mount Lofty Ranges: Threatened Species Profile – Yellow-tailed Black Cockatoo" (PDF). Department for Environment and Heritage – Biodiversity. Adelaide, South Australia: Department for Environment and Heritage, South Australian Government. Retrieved 2 February 2020.

- Way, S. L.; van Weenen, Jason (2008). "Eyre Peninsula Yellow-tailed Black-Cockatoo Calyptorhynchus funereus whitei Regional Recovery Plan" (PDF). Department for Environment and Heritage – Biodiversity. Department for Environment and Heritage, South Australian Government. Retrieved 2 February 2020.

- Forshaw (2002), p. 67.

- King, C. E.; Heinhuis, H.; Brouwer, K. (2000). "Management and husbandry of black cockatoos Calyptorhynchus spp. in captivity". International Zoo Yearbook. 37 (1): 87–116. doi:10.1111/j.1748-1090.2000.tb00710.x.

- Forshaw (2002), p. 68.

- "Appendices I, II and III". CITES. 22 May 2009. Archived from the original on 17 March 2010. Retrieved 18 March 2010.

- Cameron, p. 169.

Cited texts

- Cameron, Matt (2008). Cockatoos (1st ed.). Collingwood, Victoria: CSIRO Publishing. ISBN 978-0-643-09232-7.

- Forshaw, Joseph M. (2006). Parrots of the World; an Identification Guide. Illustrated by Frank Knight. Princeton University Press. ISBN 0-691-09251-6.

- Forshaw, Joseph M.; Cooper, William T. (2002). Australian Parrots (3rd ed.). Robina: Alexander Editions. ISBN 0-9581212-0-6.

- Higgins, P. J. (1999). Handbook of Australian, New Zealand and Antarctic Birds. Volume 4: Parrots to Dollarbird. Melbourne: Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-553071-3.

- Lendon, Alan H. (1973). Australian Parrots in Field and Aviary. Angus & Robertson. ISBN 0-207-12424-8.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Yellow-tailed black cockatoo. |

| Wikispecies has information related to Calyptorhynchus funereus |

- "Yellow-tailed black cockatoo media". Internet Bird Collection.