Glossy black cockatoo

The glossy black cockatoo (Calyptorhynchus lathami), is the smallest member of the subfamily Calyptorhynchinae found in eastern Australia. Adult glossy black cockatoos may reach 50 cm (19.5 in) in length. They are sexually dimorphic. Males are blackish brown, except for their prominent red tail bands; the females are dark brownish with some yellow spotting. Three subspecies are recognised.

| Glossy black cockatoo | |

|---|---|

.jpg) | |

| C. l. halmaturinus on Kangaroo Island | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Aves |

| Order: | Psittaciformes |

| Family: | Cacatuidae |

| Genus: | Calyptorhynchus |

| Subgenus: | Calyptorhynchus |

| Species: | C. lathami |

| Binomial name | |

| Calyptorhynchus lathami Temminck, 1807 | |

| Subspecies | |

|

C. (C.) l. lathami | |

| |

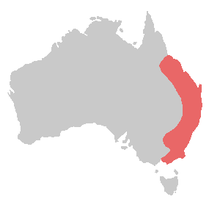

| Glossy black cockatoo range (in red) | |

Taxonomy

The glossy black cockatoo was first described by Dutch naturalist Coenraad Jacob Temminck in 1807. The scientific name honours the English ornithologist John Latham.

The glossy black cockatoo's closest relative is the red-tailed black cockatoo; the two species form the subgenus Calyptorhynchus within the genus of the same name.[2] They are distinguished from the other black cockatoos of the subgenus Zanda by their significant sexual dimorphism and calls of the juveniles; one a squeaking begging call, the other a vocalization when swallowing food.[2][3]

Subspecies

The three subspecies were proposed by Schodde et al. in 1993,[4] although parrot expert Joseph Forshaw has reservations due to their extremely minimal differences.[5]

- C. l. lathami: (rare) The eastern subspecies found between southeastern Queensland and Mallacoota in Victoria, with isolated pockets in Eungella in central Queensland and the Riverina and Pilliga forest.[6] It is associated with casuarina woodland.

- C. l. erebus: Occurs in central Queensland from Eungulla near Mackay south to Gympie[4]

- C. l. halmaturinus: (endangered) The Kangaroo Island subspecies[7] has been listed by the Australian Government as endangered. Restricted to the northern and western parts of the island, the population was as low as 158 individuals at one point but recovered to about 370 in 2019.[7] It feeds on the drooping she-oak (Allocasuarina verticillata) and the sugar gum (Eucalyptus cladocalyx)[8] In particular, the bird specialises in the most recent season's cones of Allocasuarina verticillata over older cones of that species and Allocasuarina littoralis. It holds the cones in its foot and shreds them with its powerful bill before removing the seeds with its tongue.[9] In early 2020, during the 2019-2020 Australian bushfire season, bushfire warnings were issued for the entirety of Kangaroo Island,[10] giving rise to warnings from scientists that the continued viability of this subspecies in the wild might be doomed as its drooping she-oak food supply undergoes destruction by the fires.[11][12] As of 6 January 2020, at least 170,000 hectares (one third of the island's area) had burnt.[13] Occasional respites in the weather offer at least temporary relief from the bushfires; a full assessment of the status of the Kangaroo Island subspecies and its supporting ecosystem will take place after the ongoing bushfire crisis has passed.[14] Reliable funding for the successful program to protect this subspecies – primarily from predation by the common brush tail possum[15] – ended several years ago.[16]

Description

Like the related red-tailed black cockatoo, this species is sexually dimorphic. The male glossy black cockatoo is predominantly black with a chocolate-brown head and striking caudal red patches. The female is a duller dark brown, with flecks of yellow in the tail and collar. The female's tail is barred whereas the male's tail is patched. An adult will grow to be about 46–50 cm (18–19.5 in) in length. The birds are found in open forest and woodlands, and usually feed on seeds of the she-oak (Casuarina spp.)

Conservation Status

Like most species of parrots, the glossy black cockatoo is protected by the Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species of Wild Fauna and Flora (CITES) with its placement on the Appendix II list of vulnerable species, which makes the import, export, and trade of listed wild-caught animals illegal.[17][18]

Glossy black cockatoos generally are not listed as threatened on the Environment Protection and Biodiversity Conservation Act 1999, however the Kangaroo Island subspecies (C. l. halmaturinis) was added to the list as endangered.

State of Victoria, Australia

- The eastern subspecies of the glossy black cockatoo (C. l. lathami) is listed as threatened on the Victorian Flora and Fauna Guarantee Act 1988.[19] Under this act, an "Action Statement" for the recovery and future management of this species has not been prepared.[20]

- On the 2007 advisory list of threatened vertebrate fauna in Victoria, the subspecies C. l. lathami is listed as vulnerable.[21]

State of Queensland, Australia

C. l. lathami is listed as vulnerable by the Queensland, Environmental Protection Agency.

References

- BirdLife International (2012). "Calyptorhynchus lathami". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. 2012. Retrieved 26 November 2013.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Forshaw, p. 89

- Courtney, J (1996). "The juvenile food-begging calls, food-swallowing vocalisation and begging postures in Australian Cockatoos". Australian Bird Watcher. 16: 236–49.

- Schodde R, Mason IJ & Wood JT. (1993). Geographical differentiation in the Glossy Black Cockatoo Calyptorhynchus lathami (Temminck), and its history. Emu 93: 156-166

- Forshaw, Joseph M. & Cooper, William T. (2002): Australian Parrots (3rd ed). Press, Willoughby, Australia. ISBN 0-9581212-0-6

- Blakers M, Davies SJJF, Reilly PN (1984) The Atlas of Australian Birds. RAOU and Melbourne University press, Melbourne.

- "Glossy black cockatoo". www.naturalresources.sa.gov.au. Natural Resources Kangaroo Island. Kangaroo Island Natural Resources Management Board. 27 June 2017. Archived from the original on 7 April 2019. Retrieved 10 January 2020.

- Joseph L (1982) The Glossy Black Cockatoo on Kangaroo Island Emu 82 46-49

- Crowley, GM; Garnett S (2001). "Food value and tree selection by Glossy Black-Cockatoos Calyptorhynchus lathami". Austral Ecology. 26 (1): 116–26. doi:10.1046/j.1442-9993.2001.01093.x.

- "Kangaroo Island bushfire emergency sees tourist lodges ravaged as firefighters battle 'unstoppable' blaze". www.abc.net.au. 2 January 2020. Archived from the original on 3 January 2020. Retrieved 4 January 2020.

- Roper, Erika [@_erikaroper] (3 January 2020). "This is likely to be the end for the Endangered Kangaroo Island subspecies of the Glossy #BlackCockatoos. These cockies are dependent on Kangaroo Island's Drooping Sheoak trees for food. There are only ~300 birds left with nowhere to go. Wildlife can't evacuate. #AustraliaBurning" (Tweet). Retrieved 4 January 2020 – via Twitter. (Other source information is linked in the Twitter thread)

- "Bushfires take a devastating toll on Kangaroo Island's unique wildlife". www.smh.com.au. 6 January 2020. Archived from the original on 5 January 2020. Retrieved 6 January 2020.

- "Kangaroo Island fires continue as locals count cost of damage to infrastructure, animals". ABC (Australia). 7 January 2020.

- Roper, Erika [@_erikaroper] (4 January 2020). "A Glossy #BlackCockatoos update from @daniteixeira___, who studied the Kangaroo Island population for her PhD. Thanks to the weather change the fires were not as severe as expected, so some habitat remains. Lots of work to do to restore the island" (Tweet). Retrieved 5 January 2020 – via Twitter.

- Hill, Tony (9 December 2015). "Glossy black cockatoo numbers increase on Kangaroo Island thanks to recovery program". www.abc.net.au. Archived from the original on 5 January 2020. Retrieved 11 January 2020.

- Teixeira, Daniella [@daniteixeira___] (4 January 2020). "We know that protecting nests from possum predation is the most important thing to keep doing each year. Nest predation is almost 100% on unprotected nests. Nest protection takes a massive amount of manual labor, maintaining iron collars and pruning canopys" (Tweet). Retrieved 5 January 2020 – via Twitter. (Final tweet in a 3-tweet thread.)

- "Appendices I, II and III". CITES. 22 May 2009. Archived from the original on 29 December 2007. Retrieved 18 March 2010.

- Cameron, p. 169.

- Department of Sustainability and Environment, Victoria Archived July 18, 2005, at the Wayback Machine

- Department of Sustainability and Environment, Victoria Archived September 11, 2006, at the Wayback Machine

- Victorian Department of Sustainability and Environment (2007). Advisory List of Threatened Vertebrate Fauna in Victoria - 2007. East Melbourne, Victoria: Department of Sustainability and Environment. p. 15. ISBN 978-1-74208-039-0.

Cited texts

- Cameron, Matt (2008). Cockatoos (1st ed.). Collingwood, Victoria: CSIRO Publishing. ISBN 0-643-09232-3.

- Forshaw, Joseph M; William T. Cooper (2002). Australian Parrots (3rd ed.). Robina: Alexander Editions. ISBN 0-9581212-0-6.

- Flegg, Jim. Birds of Australia: Photographic Field Guide Sydney: Reed New Holland, 2002. (ISBN 1-876334-78-9)

- Garnett, S. (1993) Threatened and Extinct Birds Of Australia. RAOU. National Library, Canberra. ISSN 0812-8014

External links

- World Parrot Trust Parrot Encyclopedia - Species Profiles

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Calyptorhynchus lathami. |

| Wikispecies has information related to Calyptorhynchus lathami |