Worms, Germany

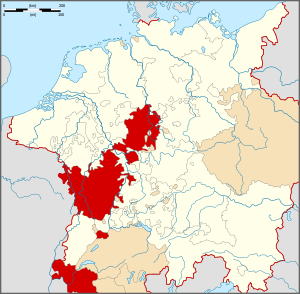

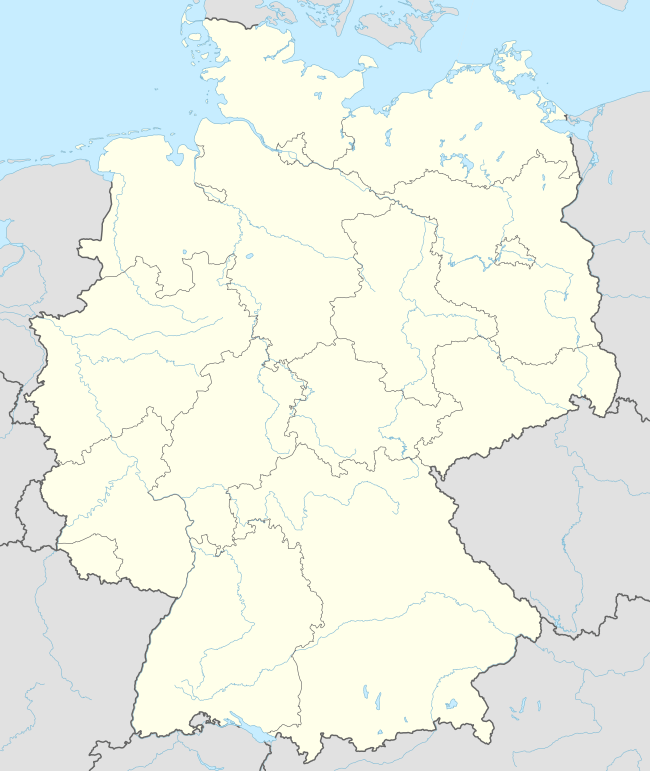

Worms (German pronunciation: [vɔɐ̯ms]) is a city in Rhineland-Palatinate, Germany, situated on the Upper Rhine about 60 kilometres (40 mi) south-southwest of Frankfurt-am-Main. It had approximately 82,000 inhabitants as of 2015.[2]

Worms | |

|---|---|

Nibelungen Bridge over the Rhine at Worms | |

Coat of arms | |

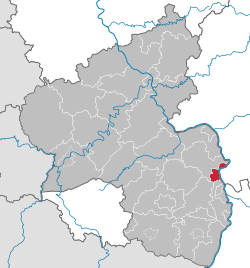

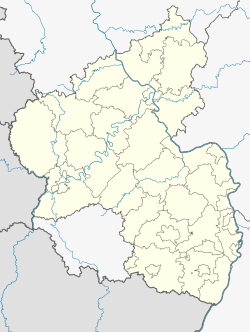

Location of Worms within Rheinland-Pfalz  | |

Worms  Worms | |

| Coordinates: 49°37′55″N 08°21′55″E | |

| Country | Germany |

| State | Rhineland-Palatinate |

| District | Urban district |

| Government | |

| • Lord Mayor | Adolf Kessel (CDU) |

| Area | |

| • Total | 108.73 km2 (41.98 sq mi) |

| Highest elevation | 167 m (548 ft) |

| Lowest elevation | 100 m (300 ft) |

| Population (2018-12-31)[1] | |

| • Total | 83,330 |

| • Density | 770/km2 (2,000/sq mi) |

| Time zone | CET/CEST (UTC+1/+2) |

| Postal codes | 67547–67551 |

| Dialling codes | 06241, 06242, 06246, 06247 |

| Vehicle registration | WO |

| Website | www |

A pre-Roman foundation, Worms is one of the oldest cities in northern Europe. It was the capital of the Kingdom of the Burgundians in the early 5th century and hence the scene of the medieval legends referring to this period, notably the first part of the Nibelungenlied. Worms has been a Roman Catholic bishopric since at least 614, and was an important palatinate of Charlemagne. Worms Cathedral is one of the Imperial Cathedrals and among the finest examples of Romanesque architecture in Germany. Worms prospered in the High Middle Ages as an Imperial Free City. Among more than a hundred Imperial Diets held at Worms, the Diet of 1521 (commonly known as the Diet of Worms) ended with the Edict of Worms in which Martin Luther was declared a heretic. Today, the city is an industrial centre and is famed as the origin of Liebfraumilch wine. Other industries include chemicals, metal goods and fodder.

Geography

Geographic location

Worms is located on the west bank of the river Rhine between the cities of Ludwigshafen and Mainz. On the northern edge of the city the Pfrimm flows into the Rhine, and on the southern edge the Eisbach flows into the Rhine.

Boroughs

Worms has 13 boroughs (or "Quarters") around the city centre. They are as follows:

| Name | Population | Direction and distance from city centre |

|---|---|---|

| Abenheim | 2,744 | Northwest (10 kilometres (6.2 mi)) |

| Heppenheim | 2,073 | Southwest (9 kilometres (5.6 mi)) |

| Herrnsheim | 6,368 | North (5 kilometres (3.1 mi)) |

| Hochheim | 3,823 | Northwest |

| Horchheim | 4,770 | Southwest (4.5 kilometres (2.8 mi)) |

| Ibersheim | 692 | North (13 kilometres (8.1 mi)) |

| Leiselheim | 1,983 | West (4 kilometres (2.5 mi)) |

| Neuhausen | 10,633 | North |

| Pfeddersheim | 7,414 | West (7 kilometres (4.3 mi)) |

| Pfiffligheim | 3,668 | West |

| Rheindürkheim | 3,021 | North (8 kilometres (5.0 mi)) |

| Weinsheim | 2,800 | Southwest (4 kilometres (2.5 mi)) |

| Wiesoppenheim | 1,796 | South West (5.5 kilometres (3.4 mi)) |

Climate

The climate in the Rhine Valley is temperate in winter and enjoyable in summer. Rainfall is below average for the surrounding areas. Winter snow accumulation is low and often melts quickly.

History

Antiquity

Worms was in ancient times a Celtic city named Borbetomagus, perhaps meaning "water meadow".[3] Later it was conquered by the Germanic Vangiones. In 14 BC, Romans under the command of Drusus captured and fortified the city, and from that time onwards a small troop of infantry and cavalry were garrisoned there. The Romans renamed the city as Augusta Vangionum, after the then-emperor and the local tribe. The name does not seem to have taken hold, however, and from Borbetomagus developed the German Worms and Latin Wormatia; as late as the modern period, the city name was written as Wormbs.[4] The garrison grew into a small town with a regular Roman street plan, a forum, and temples for the main gods Jupiter, Juno, Minerva (whose temple was the site of the later cathedral), and Mars.

Roman inscriptions, altars, and votive offerings can be seen in the archaeological museum, along with one of Europe's largest collections of Roman glass. Local potters worked in the town's south quarter. Fragments of amphoras contain traces of olive oil from Hispania Baetica, doubtless transported by sea and then up the Rhine by ship.

During the disorders of 411–13 AD, the Roman usurper Jovinus established himself in Borbetomagus as a puppet-emperor with the help of King Gunther of the Burgundians, who had settled in the area between the Rhine and Moselle some years before. The city became the capital of the Burgundian kingdom under Gunther (also known as Gundicar). Few remains of this early Burgundian kingdom survive, because in 436 it was all but destroyed by a combined army of Romans (led by Aëtius) and Huns (led by Attila); a belt clasp found at Worms-Abenheim is a museum treasure. Provoked by Burgundian raids against Roman settlements, the combined Romano-Hunnic army destroyed the Burgundian army at the Battle of Worms (436), killing King Gunther. It is said that 20,000 were killed. The Romans led the survivors southwards to the Roman district of Sapaudia (modern day Savoy). The story of this war later inspired the Nibelungenlied. The city appears on the Peutinger Map, dated to the 4th century.

Middle Ages

Imperial City of Worms Reichsstadt Worms | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 11th century–1795 | |||||||||

| Status | Free Imperial City of the Holy Roman Empire | ||||||||

| Government | Republic | ||||||||

| Historical era | Middle Ages | ||||||||

• City founded | before 14 BCE | ||||||||

• Gained Reichsfreiheit | between 1074 and 1184 11th century | ||||||||

• Concordat of Worms | 1122 | ||||||||

• Reichstag concluded Imperial Reform | 1495 | ||||||||

| 1521 | |||||||||

• Sacked by French during War of Grand Alliance | 1689 | ||||||||

• Occupied by France | 1789–1816 1795 | ||||||||

| 1816 | |||||||||

| |||||||||

Worms was a Roman Catholic bishopric from at least 614 until 1802, with an even earlier mention in 346. In the Frankish Empire, the city was the location of an important palatinate of Charlemagne, who built one of his many administrative palaces here. The bishops administered the city and its territory. The most famous of the early medieval bishops was Burchard of Worms. However, after Worms became an Imperial Free City, the bishops resided at Ladenburg and only had jurisdiction over the Cathedral in Worms itself.

The Cathedral (Wormser Dom), dedicated to St Peter, is one of the finest examples of Romanesque architecture in Germany. Alongside the nearby Romanesque cathedrals of Speyer and Mainz, it is one of the so-called Kaiserdome (Imperial Cathedrals). Some parts in early Romanesque style from the 10th century still exist, while most parts are from the 11th and 12th centuries, with some later additions in Gothic style (see the external links below for pictures).

Four other Romanesque churches as well as the Romanesque old city fortification still exist, making the city Germany's second in Romanesque architecture only to Cologne.

Worms prospered in the High Middle Ages. Having received far-reaching privileges from King Henry IV (later Emperor Henry III) as early as 1074, the city later became an Imperial Free City, being independent of any local ruler and responsible only to the Holy Roman Emperor himself. As a result, Worms was the site of several important events in the history of the Empire. In 1122 the Concordat of Worms was signed; in 1495, an Imperial Diet met here and made an attempt at reforming the disintegrating Imperial Circle Estates by the Imperial Reform. Most important, among more than a hundred Imperial Diets held at Worms, that of 1521 (commonly known as the Diet of Worms) ended with the Edict of Worms, in which Martin Luther was declared a heretic after refusing to recant his religious beliefs. Worms was also the birthplace of the first Bibles of the Reformation, both Martin Luther's German Bible and William Tyndale's first complete English New Testament by 1526.[5]

The city, known in medieval Hebrew by the name Varmayza or Vermaysa (ורמיזא, ורמישא), was a centre of medieval Ashkenazic Judaism. The Jewish community was established there in the late 10th century, and Worms's first synagogue was erected in 1034. In 1096, eight hundred Jews were murdered by crusaders and the local mob. The Jewish Cemetery in Worms, dating from the 11th century, is believed to be the oldest surviving in situ cemetery in Europe. The Rashi Synagogue, which dates from 1175 and was carefully reconstructed after its desecration on Kristallnacht, is the oldest in Germany. Prominent students, rabbis, and scholars of Worms include Shlomo Yitzhaki (Rashi) who studied with R. Yizhak Halevi, Elazar Rokeach, Maharil, and Yair Bacharach. At the rabbinical synod held at Worms at the turn of the 11th century, Rabbi Gershom ben Judah (Rabbeinu Gershom) explicitly prohibited polygamy for the first time. For hundreds of years, until Kristallnacht in 1938, the Jewish Quarter of Worms was a centre of Jewish life. Worms today has only a very small Jewish population, and a recognizable Jewish community as such no longer exists. However, after renovations in the 1970s and 1980s, many of the buildings of the Quarter can be seen in a close-to-original state, preserved as an outdoor museum.

Modern era

In 1689 during the Nine Years' War, Worms (like the nearby towns and cities of Heidelberg, Mannheim, Oppenheim, Speyer and Bingen) was sacked by troops of King Louis XIV of France, though the French only held the city for a few weeks. In 1743 the Treaty of Worms was signed, forming a political alliance between Great Britain, Austria and the Kingdom of Sardinia. In 1792 the city was occupied by troops of the French First Republic during the French Revolutionary Wars. The Bishopric of Worms was secularized in 1801, with the city being annexed into the First French Empire. In 1815 Worms passed to the Grand Duchy of Hesse in accordance with the Congress of Vienna and the city was subsequently administered within Rhenish Hesse.

After the Battle of the Bulge, in early 1945 Allied armies advanced into the Rhineland in preparation for a massive assault into the heart of the Reich. Worms was a German strongpoint on the west bank of the Rhine and the forces there resisted the Allied advance tenaciously. Worms was thus heavily bombed by the Royal Air Force in two attacks on Feb. 21 and March 18, 1945. A post-war survey estimated that 39 per cent of the town's developed area was destroyed. The RAF attack on Feb. 21 was aimed at the main railway station on the edge of the inner city, and at chemical plants southwest of the inner city, but also destroyed large areas of the city centre. Carried out by 334 bombers, the attack in a few minutes rained 1,100 tons of bombs on the inner city, and Worms Cathedral was among the buildings set on fire. The Americans did not enter the city until the Rhine crossings began after the seizure of the Remagen Bridge.

In the attacks, 239 inhabitants were killed and 35,000 (60 percent of the population of 58,000) were made homeless. A total of 6,490 buildings were severely damaged or destroyed. After the war, the inner city was rebuilt, mostly in modern style. Postwar, Worms became part of the new state of Rhineland-Palatinate; the borough Rosengarten, on the east bank of the Rhine, was lost to Hesse.

Worms today fiercely vies with the cities Trier and Cologne for the title of "Oldest City in Germany." Worms is the only German member of the Most Ancient European Towns Network.[6][7] A multimedia Nibelungenmuseum was opened in 2001, and a yearly festival right in front of the Dom, the Cathedral of Worms, attempts to recapture the atmosphere of the pre-Christian period.

In 2010 the Worms synagogue was firebombed. Eight corners of the building were set ablaze, and a Molotov cocktail was thrown at a window. There were no injuries. Kurt Beck, Minister-President of Rhineland-Palatinate, condemned the attack and vowed to mobilize all necessary resources to find the perpetrators, saying, "We will not tolerate such an attack on a synagogue".[8]

Main sights

- The renovated (1886–1935)[9] Romanesque Cathedral, dedicated to St Peter (12th-13th century)

- Reformation Memorial church of the Holy Trinity, the city's largest Protestant church (17th century)

- St Paul's Church (Pauluskirche) (13th century)

- St Andrew's Collegiate Church (Andreaskirche) (13th century)

- St Martin's Church (Martinskirche) (13th century)

- Liebfrauenkirche (15th century)

- Luther Monument (Lutherdenkmal) (1868) (designed by Ernst Rietschel)

- Rashi Synagogue

- Jewish Museum in the Rashi-House

- Jewish Cemetery

- Nibelungen Museum, celebrating the Middle High German epic poem Das Nibelungenlied (The Song of the Nibelungs)

- Magnuskirche, the city's smallest church which possibly originates from the 8th century

International relations

Twin towns — sister cities

Worms is twinned with:

Other relations

Notable citizens

A–K

- Samuel Adler (1809–1891), noted Reform rabbi, was born in Worms[10]

- Curtis Bernhardt (1899–1981), German film director

- Hans Diller (1905–1977), German classical scholar specializing in Ancient Greek medicine

- Ludwig Edinger (1855–1918), German anatomist and neurologist

- Ferdinand Eberstadt (1808–1888), textile merchant and mayor of Worms

- Hans Folz (1435/1440–1513), in Worms, notable medieval German author

- Friedrich Gernsheim (1839–1916), German composer, conductor and pianist

- Florian Gerster (born 1949), politician (SPD), former chairman of the Federal Employment Agency

- Petra Gerster (born 1955), German television journalist (ZDF)

- Johann Nikolaus Götz (1721–1781), poet

.jpg)

- Siegfried Guggenheim (1873–1961), lawyer, notary and art collector

- Heribert of Cologne (c. 970–1021, archbishop-elector of Cologne and Chancellor of the Holy Roman Empıre

- Richard Hildebrandt (1897–1952), politician in Nazi Germany and member of the Reichstag executed for war crimes

- Timo Hildebrand (born 1979), German national footballer, born in Worms

- Hans Hinkel (1901–1960), German journalist and Nazi cultural functionary

- Isaac ben Eliezer Halevi (d. 1070), French rabbi

- Hanya Holm (1893–1992), choreographer, dancer, educator and one of the founders of American Modern Dance

- Vladimir Kagan (1927–2016), furniture designer

L–Z

- Solomon Loeb (1828–1903), American banker and philanthropist

- Minna of Worms (died 1096), influential Jewish citizen, victim of the Worms massacre (1096)

- Rabbi Meir of Rothenburg (1215–1293), German rabbi and poet, a major author of the tosafot on Rashi's commentary on the Talmud

- Conrad Meit (or Conrat Meit) (1480s–1550/1551), Renaissance sculptor, mostly in the Low Countries

- Saint Erentrude, or Erentraud (c. 650–710), virgin saint of the Roman Catholic Church

- Rabbi Shlomo Yitzhaki (Rashi) (1040–1105), studied in the Worms Yeshiva in 1065 to 1070

- Hugo Sinzheimer (1875–1945), legal scholar, member of the Constitutional Convention of 1919

- Hermann Staudinger (1881–1965), organic chemist, Nobel Prize in Chemistry 1953

- Rudi Stephan (1887–1915), German composer

- Monika Stolz (born 1951), politician (CDU), Member of Landtag Baden-Württemberg since 2001

- Ida Straus (1849–1912), wife of Isidor Straus, co-owner of the Macy's department store, voluntarily remained with husband on board the RMS Titanic

- Emil Stumpp (1886–1941), cartoonist, died in jail after doing an unflattering portrait of Adolf Hitler

- Rod Temperton (1949–2016), English songwriter, record producer and musician; he wrote Heatwave, Michael Jackson and George Benson's hits, also worked with Quincy Jones and was awarded a Grammy Award

- Markus Weinmann (born 1974), German agricultural scientist in the area of plant physiology

See also

References

- "Bevölkerungsstand 2018 - Gemeindeebene". Statistisches Landesamt Rheinland-Pfalz (in German). 2019.

- Statistisches Landesamt (2015-12-31). "Bevölkerung der Gemeinden am 31.Dezember 2015 - A1033_201522_hj_G.pdf" (pdf). statistik.rlp.de (in German). Rheinland Pfalz. p. 15. Retrieved 2017-11-27.

- "Etymologie". Etymologie.info.

damit der Bedeutung von 'Borbetomagus' = dt. 'Wasserwiese'

- see Apologia Der Stadt Wormbs Contra Bistum Wormbs, 1694.

- Teems, David. "Tyndale: The man who gave God an English voice." Nashville: Thomas Nelson (2012). Chapter 4.

- MAETN (1999). "diktyo". classic-web.archive.org. Archived from the original on October 22, 2005. Retrieved 19 May 2011.

- Worms city council (2011). "worms.de > Kultur > älteste deutsche Stadt". worms.de. Archived from the original on 19 July 2011. Retrieved 19 May 2011.

- "Worms synagogue fire-bombed". Haaretz. 17 May 2010.

- "Dom St. Peter Worms". pg-dom-st-peter-worms.bistummainz.de. Retrieved 2019-01-22.

- Who Was Who in America, Historical Volume, 1607-1896. Marquis Who's Who. 1967.

Further reading

- Roemer, Nils H. German City, Jewish Memory: The Story of Worms (Brandeis University Press, 2010) ISBN 978-1-58465-922-8 online review

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Worms. |

| Wikivoyage has a travel guide for Worms. |

- The Official website of the city of Worms (in English)

- Nibelungenmuseum website (in English)

- wormser-dom.de, website of the Worms Cathedral with pictures (in German) (click on the "Bilder" link in the left panel)

- Wormatia, Worms football club (in German)