Women in Classical Athens

The study of the lives of women in Classical Athens has been a significant part of classical scholarship since the 1970s. The knowledge of Athenian women's lives comes from a variety of ancient sources. Much of it is literary evidence, primarily from tragedy, comedy, and oratory; supplemented with archaeological sources such as epigraphy and pottery. All of these sources were created by—and mostly for—men: there is no surviving ancient testimony by Classical Athenian women on their own lives.

Female children in classical Athens were not formally educated; rather, their mothers would have taught them the skills they would need to run a household. They married young, often to much older men. When they married, Athenian women had two main roles: to bear children, and to run the household. The ideal Athenian woman did not go out in public or interact with men she was not related to, though this ideology of seclusion would only have been practical in wealthy families. In most households, women were needed to carry out tasks such as going to the market and drawing water, which required taking time outside the house where interactions with men were possible.

Legally, women's rights were limited. They were barred from political participation, and Athenian women were not permitted to represent themselves in law, though it seems that metic women could. (A metic was a resident alien—free, but without the rights and privileges of citizenship). They were also forbidden from conducting economic transactions worth more than a nominal amount. However, it seems that this restriction was not always obeyed. In poorer families, women would have worked to earn money, and would also have been responsible for household tasks such as cooking and washing clothes. Athenian women had limited capacity to own property, although they could have significant dowries, and could inherit items.

The area of civic life in which Athenian women were most free to participate was the religious and ritual sphere. Along with important festivals reserved solely for women, they participated in many mixed-sex ritual activities. Of particular importance was the cult of Athena Polias, whose priestess held considerable influence. Women played an important role in the Panatheneia, the annual festival in honour of Athena. Women also played an important role in domestic religious rituals.

Historiography

Sources

It cannot be said too strongly or too frequently that the selection of book-texts now available to us does not represent Greek society as a whole.

— John J. Winkler, The Constraints of Desire: The Anthropology of Sex and Gender in Ancient Greece[2]

The major sources for the lives of women in classical Athens are literary, political and legal,[3] and artistic.[4] As women play a prominent role in much Athenian literature, it initially seems as though there is a great deal of evidence for the lives and experiences of Athenian women.[5] However, the surviving literary evidence is written solely by men: ancient historians have no direct access to the beliefs and experiences of Classical Athenian women.[5] It is because of this that John J. Winkler writes in The Constraints of Desire that "most of our surviving documents simply cannot be taken at face value when they speak of women".[6]

According to Sarah Pomeroy, "tragedies cannot be used as an independent source for the life of the average woman"[7] since the position of women in tragedy was dictated by their role in the pre-classical myths used by the tragedians as sources.[8] However, A. W. Gomme's 1925 "The Position of Women in Athens in the Fifth and Fourth Centuries" relied heavily on tragedy as a source and argued that classical Athenian tragedy modelled its female characters on the lives of contemporary women.[9] The relevance of comedy as evidence is also disputed. Pomeroy writes that since it deals more often with ordinary people than with mythological heroes and heroines, comedy is a more reliable source than tragedy for social history.[7] Gomme, however, criticised the use of Old Comedy as evidence of daily life "for anything may happen in Aristophanes".[10]

Another major source for the lives of women in classical Athens is surviving legal speeches. Since many concern inheritance, they are valuable sources of Athenian attitudes toward gender and the family.[11] Although these sources must be treated with caution because trials in classical Athens were "essentially rhetorical struggles",[12] they are useful for information about the ideologies of gender, family and household.[11] These speeches also frequently contain references to, and even the texts of, Athenian laws not otherwise preserved. The pseudo-Demosthenic speech Against Neaera, for instance, contains a law on adultery which is not otherwise attested.[13]

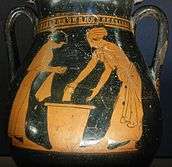

Archaeological and iconographical evidence provide a wider range of perspectives than literature. Producers of ancient Athenian art are known to have included metics.[14] Some of this art may have been produced by women and children.[14] Although the art produced (particularly pottery, grave stelai and figurines) was used by a wider range of people than much Athenian literature was—including women and children[14]—it is not known how accurately the iconography of classical art mapped the reality of classical society.[15]

Approaches

Before the 20th century, and in some cases as late as the 1940s, historians largely took ancient literary sources at face value as evidence for the lives of women in the ancient world.[16] In the middle of the 20th century this began to change. Early innovations in the study of women in ancient history began in France, as the Annales School began to take a greater interest in underrepresented groups. Robert Flacelière was an influential early author on women in Greece.[17] Around the same time, feminist philosophy, such as Simone de Beauvoir's The Second Sex also examined the lives of women in the classical world.[17]

Influenced by second-wave feminism, the study of women in antiquity became widespread in the English-speaking world in the 1970s.[17] The amount of scholarship on women in the ancient world has increased dramatically since then. The first major publication in the field was a 1973 special issue of the journal Arethusa,[18] which aimed to look at women in the ancient world from a feminist perspective.[17] In 1975, the first edition of Sarah Pomeroy's Goddesses, Whores, Wives, and Slaves was published. This has been described as "the inauguration of women's studies within classics".[19] Lin Foxhall called Pomeroy's book "revolutionary" and "a major step forward" from previous English-language scholarship on ancient women.[20] According to Shelley Haley, Pomeroy's work "legitimized the study of Greek and Roman women in ancient times".[21]

However, classics has been characterised as a "notoriously conservative" field,[21] and initially women's history was slow to be adopted: from 1970 to 1985, only a few articles on ancient women were published in major journals.[22] In 1976, a single review was able to cover "the entire field of recent scholarship on women in all of classical antiquity".[23] However, by 1980, writing about women in classical Athens was called "positively trendy",[3] and in 1989 women's studies was described as "one of the most exciting growth points" in classics.[24]

Along with feminist theory, the work of Michel Foucault, influenced by structuralism and post-structuralism, has had a significant impact on the study of gender in classical antiquity.[25] Foucault has been praised for looking at gender through the lens of social systems.[26] According to Lin Foxhall, his approach has "had more impact on the scholarship of gender than anything since second-wave feminism"[25] and is "virtually canonical in some quarters".[27] However, Foucault's work has been criticised for its "shallow discussion of women as historical subjects".[28]

Scholarly interest in the lives of women in the ancient world has continued to increase. By 2000, a review of books focused on women in ancient Greece published over a three-year period could cover eighteen works without being exhaustive.[23] The range of subjects covered by women's historians also increased substantially; in 1980 the question of women's status was the most important topic to historians of Athenian women,[3] but by 2000 scholars were also working on "gender, the body, sexuality, masculinity and other topics".[23]

Until the 1980s, scholars of women in classical Athens were primarily interested in the status of women[29] and how they were viewed by men.[3] Early feminist scholarship aimed to assert that women were significant in ancient history and to demonstrate how they had been oppressed.[30] Early scholars held that Athenian women had an "ignoble" place,[31] but in 1925 this position was challenged by Arnold Wycombe Gomme. According to Gomme, women had high social status despite their limited legal rights; his view has reinforced that position ever since.[32] Pomeroy attributes the variety of viewpoints to the types of evidence prioritised by scholars, with those arguing for the high status of Athenian women predominantly citing tragedy and those arguing against it emphasising oratory.[9]

With increased interest in women's history by classical scholars, a number of related disciplines have also become more significant. Classicists have become more interested in the family since the Second World War, with W. K. Lacey's 1968 The Family in Classical Greece particularly influential.[33] The history of childhood emerged as a sub-discipline of history during the 1960s,[34] and other disciplines such as the study of ancient medicine have been influenced by feminist approaches to the classics.[19]

Childhood

Infant mortality was common in classical Athens, with perhaps 25 percent of children dying at or soon after birth.[35] In addition to the natural risks of childbirth, the ancient Athenians practiced infanticide; according to Sarah Pomeroy, girls were more likely to be killed than boys.[36] Donald Engels has argued that a high rate of female infanticide was "demographically impossible",[37] although scholars have since largely dismissed this argument.[38][note 1] Although scholars have tried to determine the rate of female infanticide, Cynthia Patterson rejects this approach as asking the wrong questions; Patterson suggests that scholars should instead consider the social importance and impact of the practice.[40]

Janet Burnett Grossman writes that girls appear to be commemorated about as frequently as boys on surviving Attic gravestones, although previous scholars suggested that boys were commemorated up to twice as often.[41] If they survived, Athenian children were named in a ceremony (the dekate) ten days after birth.[42] Other Athenian ceremonies celebrating childbirth (at five, seven, and forty days after birth) were also observed.[43] Later rites of passage were apparently more common and elaborate for boys than for girls.[44]

Classical Athenian girls probably reached menarche at about age fourteen, when they would have married.[45] Girls who died before marriage were mourned for their failure to reach maturity. Memorial vases for dead girls in classical Athens often portrayed them dressed as brides, and were sometimes shaped like loutrophoroi (vases which held water used to bathe before the wedding day).[46]

Athenian girls were not formally educated; instead, their mothers taught them the domestic skills necessary for running a household. Formal education for boys consisted of rhetoric, necessary for effective political participation, and physical education in preparation for military service. These skills were not considered necessary for women, who were barred from learning them.[47] Classical art indicates that girls and boys played with toys such as spinning tops, hoops, and seesaws, and played games such as piggyback.[48] The gravestone of Plangon, an Athenian girl aged about five which is in the Glyptothek museum in Munich, shows her holding a doll; a set of knucklebones hangs on a wall in the background.[49]

More is known about the role of Athenian children in religion than about any other aspect of their lives, and they seem to have played a prominent role in religious ceremonies.[50] Girls made offerings to Artemis on the eve of their marriage, during pregnancy, and at childbirth.[35] Although girls and boys appear on the wine jugs connected with the early-spring festival of the Anthesteria, depictions of boys are far more common.[48]

Family life

Marriage

The primary role of free women in classical Athens was to marry and bear children.[46] The emphasis on marriage as a way to perpetuate the family through childbearing had changed from archaic Athens, when (at least amongst the powerful) marriages were as much about making beneficial connections as they were about perpetuating the family.[51] Athenian women typically first married much older men around age fourteen.[52][53] Before this they were looked after by their closest male relative, who was responsible for choosing their husband;[note 2][55] the bride had little say in this decision.[56] Since a classical Athenian marriage was concerned with the production of children who could inherit their parents' property,[57] women often married relatives.[55] This was especially the case of women with no brothers (epikleroi), whose nearest male relative was given the first option of marrying her.[58]

Marriage most commonly involved a betrothal (engue), before the bride was given over to her new husband and kyrios (ekdosis).[59] A less common form of marriage, practised in the case of epikleroi, required a court judgement (epidikasia).[60] Athenian women married with a dowry, which was intended to provide their livelihood.[61] Depending on the family, a dowry might have been as much as 25 percent of the family's wealth.[62] Daughters of even the poorest families apparently had dowries worth ten minae. Rich families could provide much larger dowries; Demosthenes' sister, for instance, had a dowry of two talents (120 minae).[63] Dowries usually consisted of movable goods and cash, although land was occasionally included.[62]

Only in exceptional circumstances would there have been no dowry, since the lack of one could have been interpreted as proof that no legitimate marriage occurred.[42] A dowry may have been occasionally overlooked if a bride's family connections were very favorable; Callias reportedly married Elpinice, a daughter of the noble Philaidae, to join that family and was sufficiently wealthy that her lack of a dowry did not concern him.[64]

Married women were responsible for the day-to-day running of the household. At marriage, they assumed responsibility for the prosperity of their husband's household and the health of its members.[65] Their primary responsibilities were bearing, raising and caring for children, weaving cloth and making clothes.[66] They would also have been responsible for caring for ill household members, supervising slaves, and ensuring that the household had sufficient food.[67]

In classical Athenian marriages, husband or wife could legally initiate a divorce.[46] The woman's closest male relative (who would be her kyrios if she were not married) could also do so, apparently even against the couple's wishes.[68] After divorce, the husband was required to return the dowry or pay 18 percent interest annually so the woman's livelihood would continue and she could remarry.[64] If there were children at the time of the divorce, they remained in their father's house and he remained responsible for their upbringing.[69] If a woman committed adultery, her husband was legally required to divorce her.[70] A married epikleros[note 3] would be divorced so she could marry her nearest relative.[70]

Seclusion

Lysias, Against Simon §6[72]

In classical Athens, women ideally remained apart from men.[52] This ideology of separation was so strong that a party to a lawsuit (Lysias' Against Simon) could claim that his sister and nieces were ashamed to be in the presence of their male relatives as evidence that they were respectable.[73] Some historians have accepted this ideology as an accurate description of how Athenian women lived their lives; W. B. Tyrrell, for example, said: "The outer door of the house is the boundary for the free women".[74] However, even in antiquity it was recognised that an ideology of separation could not be practiced by many Athenians. In Politics, Aristotle asked: "How is it possible to prevent the wives of the poor from going out of doors?"[75]

The ideal that respectable women should remain out of the public eye was so entrenched in classical Athens that simply naming a citizen woman could be a source of shame.[6] Priestesses were the only group of women to be exempt from this rule.[76] Thucydides wrote in his History of the Peloponnesian War, "Great honour is hers whose reputation among males is least, whether for praise or blame".[77] Women were identified by their relationships to men,[78] which could create confusion if two sisters were both referred to as the son (or brother) of the same man.[79] In law-court speeches, where a woman's position is often a key point (especially in inheritance cases), orators seem to have deliberately avoided naming them.[80] Although Demosthenes speaks about his mother and sister in five extant speeches relating to his inheritance, neither is ever named; in his body of extant work, only 27 women are named, compared with 509 men.[81] The use of a woman's name – as in the case of Neaera and Phano in Apollodoros' speech Against Neaera – has been interpreted as implying that she is not respectable.[79] John Gould has written that women named in classical Athenian oratory can be divided into three groups: women of low status, the speaker's opponents,[note 4] and the deceased.[81]

In practice, only wealthy families would have been able to implement this ideology.[83] Women's responsibilities would have forced them to leave the house frequently – to fetch water from the well or wash clothing, for example. Although wealthy families may have had slaves to enable free women to remain in the house, but most would not have had enough slaves to prevent free women from leaving at all.[84] According to Gould, even Athenian women forced to work outside the home for economic reasons would have had a conceptual (if not physical) boundary preventing them from interacting with unrelated men.[85] In contrast, Kostas Vlassopoulos has posited that some areas of Athens (such as the agora) were "free spaces" where women and men could interact.[86]

Even the most respectable citizen women emerged on ritual occasions (primarily festivals, sacrifices, and funerals), where they would have interacted with men.[87] The Thesmophoria, an important festival to Demeter which was restricted to women, was organised and conducted by Athenian citizen women.[88] Athenian women also ventured outdoors socially. David Cohen writes, "One of the most important activities of women included visiting or helping friends or relatives",[88] and even wealthy women who could afford to spend their entire lives indoors probably interacted socially with other women outside in addition to the religious and ritual occasions when they were seen in public.[89] According to D. M. Schaps (citing Cohen), the ideology of separation in classical Athens would have encouraged women to remain indoors but necessary outside activities would have overridden it.[90]

The ideology of female seclusion may have extended inside the house. Literary evidence seems to suggest that there were separate men's and women's quarters in Athenian houses.[91] In On the Murder of Eratosthenes, Euphiletos says that the women's quarters are above the men's,[92] while in Xenophon's Oeconomicus they are on the same level as the men's quarters but "separated by a bolted door".[93] However, the archaeological evidence suggests that this boundary was not as rigidly defined as the literary evidence suggests. Lisa Nevett, for instance, has argued that Athenian women were in reality only restricted to the "women's quarters" when unrelated men visited.[91]

Legal rights

The juridical status of women in Athens is beautifully indicated by the single entry under "women" in the index to Harrison's Law of Athens i: it reads simply "women, disabilities".

— John Gould, "Law, Custom and Myth: Aspects of the Social Position of Women in Classical Athens"[68]

Residents of Athens were divided into three classes: Athenians, metics, and slaves.[94] Each of these classes had different rights and obligations: for instance, Athenians could not be made slaves, while metics could.[95] Nicole Loraux writes that Athenian women were not considered citizens.[96] This is not universally accepted, however. Eva Cantarella disagrees, arguing that both of the Greek words used to denote citizenship, aste and politis, were used to refer to Athenian women.[97] Josine Blok argues that military and political service were not prerequesites of citizenship; instead, she says, it was participation in the cultic life of the polis which made a person a citizen.[98] Thus, according to Blok Athenian men and women were both considered citizens.[99] Similarly, Cynthia Patterson says that while the English word "citizen" connotes sharing in political and judicial rights, the equivalent Classical Athenian concepts were more about "being a member of the Athenian family". She thus argues that the English words "citizen" and "citizenship" are best avoided when discussing Classical Athenian concepts.[100]

In most cases, Athenian women had the same rights and responsibilities as Athenian men.[95] However, Athenian women did have some significant disabilities at law compared to their male counterparts. Like slaves and metics, they were denied political freedom,[101] being excluded from the law courts and the Assembly.[102] In some cases, if women were seen to comment on their husband's involvement in politics, they were reprimanded. Suggestions of this can be seen in a play written by Aristophanes called Lysistrata. The rights of metic women were closer to those of metic men. Metic women only paid 6 drachmas per year poll tax, compared to the 12 paid by their male counterparts,[note 5] and did not perform military service, but other than this their legal rights and responsibilities were the same as those of male metics.[103]

In Athenian law courts, juries were all male.[104] Athenian women could not appear as litigants; they were represented by their kyrios or, if he was on the other side of the dispute, by any man who wished to.[105] According to Simon Goldhill, "The Athenian court seems to have been remarkably unwilling to allow any female presence in the civic space of the law court itself".[106] Metic women, however, apparently could appear in court cases on their own behalf, and could initiate legal action.[95]

In the political sphere, men made up the Assembly and held political office.[107] Although Athenian women were formally prevented from participating in the democratic process, Kostas Vlassopoulos writes that they would have been exposed to political debate in the agora.[108] Additionally, some Athenian women do seem to have involved themselves in public affairs, despite their formal disbarment from the political arena.[109] Plutarch, in his Life of Pericles, tells two stories about Elpinice's public actions. Once, he says, she criticised Pericles for making war against other Greek cities;[110] on another occasion she pleaded with him not to prosecute her brother Cimon on charges of treason.[111]

Until the Periclean law of citizenship in 451–50, any child with an Athenian father was considered an Athenian citizen.[1] Blok suggests that in this period it was also legally possible for a child to be considered an Athenian citizen through an Athenian mother, even with a non-citizen father, though she concedes that this would have been exceptional.[112] However, other historians disagree—K. R. Walters, for instance, explicitly dismisses the possibility, arguing that without a citizen father a child had no way of gaining entry into a deme or phratry.[113] Blok suggests that the child might have instead been enrolled in the deme and phratry of the maternal grandfather.[112] After the passage of Pericles' citizenship law, the importance of Athenian women seems to have increased, although they gained no legal rights.[114]

Religion

Religion was the one area of public life in which women could participate freely;[115] according to Christopher Carey, it was the "only area of Greek life in which a woman could approach anything like the influence of a man".[116] Women's religious activities, including responsibility for mourning at funerals[117] and involvement in female and mixed-sex cult activity, were an indispensable part of Athenian society.[118] Both Athenian and non-Athenian women participated in public religious activities. The state-controlled Eleusinian mysteries, for instance, were open to all Greek speaking people, men and women, free and unfree alike.[119]

Cult of Athena

The cult of Athena Polias (the city's eponymous goddess) was central to Athenian society, reinforcing morality and maintaining societal structure.[66] Women played a key role in the cult; the priestesshood of Athena was a position of great importance,[120] and the priestess could use her influence to support political positions. According to Herodotus, before the Battle of Salamis the priestess of Athena encouraged the evacuation of Athens by telling the Athenians that the snake sacred to Athena (which lived on the Acropolis) had already left.[120]

The most important festival to Athena in Athens was the Lesser Panathenaea, held annually, which was open to both sexes.[120] Men and women were apparently not segregated during the procession leading the animals sacrificed to the altar, the festival's most religiously-significant part.[120] Metics, both men and women, also had role in the Panathenaic procession,[121] though it was subordinate to the role of the Athenians.[122] In the procession, young noble girls (kanephoroi) carried sacred baskets. The girls were required to be virgins; to prevent a candidate from being selected was, according to Pomeroy, to question her good name.[123] The sister of Harmodius was reportedly rejected as a kanephoros by the sons of Peisistratos, precipitating his assassination of Hipparchus.[124]

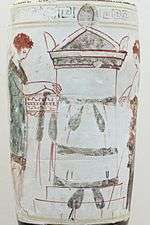

Each year, the women of Athens weaved a new peplos for a wooden statue of Athena. Every four years, for the Great Panathenaea, the peplos was for a much larger statue of Athena and could be used as a sail.[125] The task was begun by two girls chosen from those between the ages of seven and eleven, and was finished by other women.[124]

Women's festivals

Women were able to take part in almost every religious festival in classical Athens, but some significant festivals were restricted only to women.[126] The most important women's festival was the Thesmophoria, a fertility rite for Demeter which was observed by married noblewomen. During the festival women stayed for three days on Demeter's hilltop sanctuary, conducting rites and celebrating.[127] Although the specific rituals of the Thesmophoria are unknown, pigs were sacrificed and buried; the remains of those sacrificed the previous year were offered to the goddess.[128]

Most women's festivals were dedicated to Demeter,[129] but some festivals (including the Brauronia and the Arrhephoria) honoured other goddesses. Both these festivals were rites of passage in which girls became adult women. In the Brauronia, virgin girls were consecrated to Artemis of Brauron before marriage;[127] in the Arrhephoria, girls (Arrhephoroi) who had spent the previous year serving Athena left the Acropolis by a passage near the precinct of Aphrodite carrying baskets filled with items unknown to them.[130]

Theatre

The Athenian festival of the Great Dionysia included five days of dramatic performances in the Theatre of Dionysus, and the Lenaia had a dramatic competition as part of its festival. Whether women were permitted to attend the theatre during these festivals has been the subject of lengthy debate by classicists,[note 6] largely revolving around whether the theatre was considered a religious or a civic event.[132]

Jeffrey Henderson writes that women were present in the theatre, citing Plato's Laws and Gorgias as saying that drama was addressed to men, women and children.[133] Henderson also mentions later stories about Athenian theatre, such as the tale that Aeschylus' Eumenides had frightened women in the audience into miscarrying.[134] Other evidence of the presence of women at the theatre in Athens includes the absence of surviving prohibitions against their attendance and the importance of women in Athenian rituals, especially those associated with Dionysus.[132]

According to Simon Goldhill, the evidence is fundamentally inconclusive.[135] Goldhill writes that the theatre can be seen as a social and political event analogous with the Assembly and the courtroom, and women may have been excluded.[136] David Kawalko Roselli writes that although Goldhill's perspective is valuable, he does not sufficiently consider the theatre's ritual purpose.[136] If women did attend the theatre, they may have sat separately from the men.[137]

Private religion

Along with the major community-based religious rituals, women played an important role in domestic religion. They were especially important in celebrating rites of passage – especially weddings, childbirth, and funerals.[126] Women took part in a number of private rituals to prepare for and celebrate marriage. They also played a major role in funeral and mourning rituals.[138]

Before marriage, girls made dedications to Artemis, often of childhood toys and locks of hair.[139] Along with Artemis, girls made pre-marital sacrifices to Gaia and Uranus, the Erinyes and Moirai, and to their ancestors.[140] It was customary for the bride to bathe before her wedding; jars called loutrophoroi were used to draw the water, and many of these were afterwards dedicated to nymphs.[141] For instance, at a shrine to a nymph on the south slope of the Acropolis in Athens, many fragments of loutrophoroi have been discovered with the word Nymphe inscribed on them.[141]

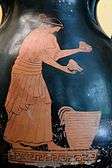

By the classical period, laws designated which women could mourn at a funeral; mourners had to be cousins of, or more closely related to, the deceased.[142] Women influenced funeral arrangements, with the speaker in Isaeus On the Estate of Ciron explaining that he acceded to his grandmother's wishes for how his grandfather would be buried.[143] This responsibility continued after the funeral, and women regularly visited the graves of family members to present offerings.[138] A tomb was customarily visited three, nine, thirty days, and a year after the funeral.[144] Images on Attic lekythoi show women bringing offerings to a grave.[145]

Economic activity

The economic power of Athenian women was legally constrained. Historians have traditionally considered that ancient Greek women, particularly in Classical Athens, lacked economic influence.[146] Athenian women were forbidden from entering a contract worth more than a medimnos of barley, enough to feed an average family for six days.[147] In at least one instance, however, an Athenian woman is known to have dealt with a significantly larger sum[148] and Deborah Lyons writes that the existence of such a law has "recently come under question".[149] Despite this, there is no evidence that Athenian women owned land or slaves (the two most valuable forms of property).[150]

Although Athenian women were not legally permitted to dispose of large sums of money, they frequently had large dowries which supported them throughout their lives.[64] Income from a dowry could be significant. The larger a woman's dowry relative to her husband's wealth, the more influence she was likely to have in the household since she retained the dowry if the couple divorced.[151] Athenian women could also acquire property by inheritance if they were the closest surviving relative,[note 7][153] but could not contractually acquire or dispose of property.[150]

Respectable Athenian women remained separate from unrelated men and Athenian citizens considered it degrading for citizen-women to work,[154] but women (free and unfree) are attested as working in a number of capacities. Women engaged in occupations which were an extension of household jobs, such as textile work and washing,[155] and those unrelated to household tasks: cobblers, gilders, net-weavers, potters, and grooms.[156]

Some Athenian citizen women were merchants,[157] and Athenian law forbade criticism of anyone (male or female) for selling in the marketplace.[88][note 8] Women would also have gone to the market to purchase goods;[159] although wealthy women owned slaves they could send on errands, poorer women went to the market themselves.[160]

Prostitution

In classical Athens, female prostitution was legal, albeit disreputable, and prostitution was taxed.[161] Prostitutes in Athens were either "pornai" or hetairai ("companions", a euphemism for higher-class prostitution).[161] Although many were slaves or metics (and state-run brothels staffed by slaves were said to have been part of Solon's reforms),[162] Athenian-born women also worked in the sex trade in Athens.[163] Pornai apparently charged one to six obols for each sexual act;[164] hetairai were more likely to receive gifts and favours from their clients, enabling to them to maintain a fiction that they were not being paid for sex.[165]

Prostitutes were often hired by the hosts of symposia as entertainment for guests, as seen in red-figure vase paintings. Prostitutes were also drawn on drinking cups as pinups for male entertainment.[166] Dancing girls and musicians entertaining at symposia might have been sexually assaulted; in Aristophanes' comedy Thesmophoriazusae, a dancing girl is treated as a prostitute and Euripides charges a guard one drachma to have sex with her.[167]

Hetairai could be the most independent, wealthy, and influential women in Athens,[168] and could form long-term relationships with rich and powerful men.[169] The most successful hetairai were free to choose their clients,[170] and sometimes became concubines of their former clients.[163]

Athenian prostitutes probably committed infanticide more frequently than married citizen women;[171] Sarah Pomeroy suggests that they would have preferred daughters – who could become prostitutes – to sons. Some prostitutes also bought slaves, and trained abandoned children to work in the profession.[171]

See also

Notes

- For instance, Mark Golden points out that Engel's argument equally applies to other pre-industrial societies in which female infanticide is known to have been practiced, and therefore cannot be valid.[39]

- When a woman married, her husband became her new kurios. His authority over his wife extended to the right to select a new husband for his widow in his will.[54]

- For example, if a man's son died, as is the case in Isaeus' speech Against Aristarchus, his daughter could become epikleros.[71]

- Gould points out that women connected with a political opponent are "a clear extension of the first category", i.e. low status women.[81] In the case of Apollodorus Against Neaera, for instance, the speaker argues that Phano is the daughter of the ex-prostitute Neaera. His use of her name is a rhetorical strategy to encourage the jury to think of her as disreputable.[82]

- This poll tax, known as the metoikion, was only paid by metics; most Athenian citizens did not pay tax.

- Marilyn Katz says that the earliest comment on the question dates back to 1592, in Isaac Casaubon's edition of Theophrastus' Characters.[131]

- Except in the case of epikleroi, whose sons inherited, with the line of inheritance being transmitted through their mother.[152]

- Steven Johnstone argues for the manuscript reading of [Demosthenes] 59.67. If he is correct, then women's ability to deal with men while working as market traders without being accused of adultery seems to also have been protected by law.[158]

References

- Osborne 1997, p. 4

- Winkler 1989, p. 19

- Gould 1980, p. 39

- Gomme 1925, p. 6

- Gould 1980, p. 38

- Winkler 1989, p. 5

- Pomeroy 1994, p. x

- Pomeroy 1994, pp. 93–94

- Pomeroy 1994, p. 59

- Gomme 1925, p. 10

- Foxhall 2013, p. 18

- Gagarin 2003, p. 198

- Johnstone 2002, p. 230, n. 3

- Beaumont 2012, p. 13

- Foxhall 2013, p. 20

- Foxhall 2013, p. 4

- Foxhall 2013, p. 6

- Arthur 1976, p. 382

- Hall 1994, p. 367

- Foxhall 2013, p. 7

- Haley 1994, p. 26

- Foxhall 2013, pp. 7–8

- Katz 2000, p. 505

- Winkler 1989, p. 3

- Foxhall 2013, p. 12

- Milnor 2000, p. 305

- Foxhall 2013, p. 14

- Behlman 2003, p. 564

- Pomeroy 1994, p. 58

- Foxhall 2013, p. 8

- Gomme 1925, p. 1

- Pomeroy 1994, pp. 58–59

- Beaumont 2012, p. 5

- Beaumont 2012, p. 7

- Garland 2013, p. 208

- Pomeroy 1994, p. 69

- Engels 1980, p. 112

- Patterson 1985, p. 107

- Golden 1981, p. 318

- Patterson 1985, p. 104

- Grossman 2007, p. 314

- Noy 2009, p. 407

- Garland 2013, p. 209

- Garland 2013, p. 210

- Pomeroy 1994, p. 68

- Pomeroy 1994, p. 62

- Pomeroy 1994, p. 74

- Oakley 2013, pp. 166–167

- Grossman 2007, p. 315

- Garland 2013, p. 207

- Osborne 1997, p. 28

- Dover 1973, p. 61

- Lyons 2003, p. 126

- Gould 1980, p. 44

- Pomeroy 1994, p. 64

- Bakewell 2008, p. 103

- Davis 1992, p. 289

- Pomeroy 1994, p. 61

- Kamen 2013, pp. 91–2

- Kamen 2013, p. 92

- Foxhall 1989, p. 32

- Cantarella 2005, p. 247

- Kapparis 1999, pp. 268–269

- Pomeroy 1994, p. 63

- Fantham et al. 1994, p. 101

- Gould 1980, p. 51

- Xenophon, Oeconomicus, 7.35–7.37

- Gould 1980, p. 43

- Pomeroy 1994, p. 65

- Cohn-Haft 1995, p. 3

- Isaeus 10.4.

- Lysias 1930, p. 75

- Lysias 3.6.

- Cohen 1989, p. 7

- Aristotle, Politics, 1300a.

- Patterson 1987, p. 53

- Thucydides, History of the Peloponnesian War 2.45.2.

- Noy 2009, p. 399

- Noy 2009, p. 405

- Schaps 1977, p. 323

- Gould 1980, p. 45

- Noy 2009, p. 401

- Dover 1973, p. 69

- Cohen 1989, pp. 8–9

- Gould 1980, p. 48

- Vlassopoulos 2007, p. 42

- Lewis 2002, p. 138

- Cohen 1989, p. 8

- Cohen 1989, p. 9

- Schaps 1998, p. 179

- Kamen 2013, p. 90

- Lysias 1.9.

- Xenophon, Oeconomicus 9.5.

- Akrigg 2015, p. 157

- Patterson 2007, p. 170

- Loraux 1993, p. 8

- Cantarella 2005, p. 245

- Blok 2009, p. 160

- Blok 2009, p. 162

- Patterson 1987, p. 49

- Rhodes 1992, p. 95

- Schaps 1998, p. 178

- Patterson 2007, pp. 164–166

- Gagarin 2003, p. 204

- Schaps 1998, p. 166

- Goldhill 1994, p. 360

- Katz 1998b, p. 100

- Vlassopoulos 2007, p. 45

- Patterson 2007, pp. 172–173

- Plutarch, Pericles, 28

- Plutarch, Pericles, 10

- Blok 2009, p. 158

- Walters 1983, p. 317

- Roy 1999, p. 5

- Dover 1973, pp. 61–62

- Carey 1995, p. 414

- Lysias 1.8.

- Gould 1980, pp. 50–51

- Pomeroy 1994, pp. 76–77

- Pomeroy 1994, p. 75

- Roselli 2011, p. 169

- Akrigg 2015, p. 166

- Pomeroy 1994, pp. 75–76

- Pomeroy 1994, p. 76

- Pomeroy 2002, p. 31

- Foxhall 2005, p. 137

- Burkert 1992, p. 257

- Burkert 1992, p. 252

- Dillon 2002, p. 191

- Burkert 1992, pp. 250–251

- Katz 1998a, p. 105

- Roselli 2011, p. 164

- Henderson 1991, p. 138

- Henderson 1991, p. 139

- Goldhill 1997, p. 66

- Roselli 2011, p. 165

- Henderson 1991, p. 140

- Fantham et al. 1994, p. 96

- Dillon 2002, p. 215

- Dillon 2002, p. 217

- Dillon 2002, p. 219

- Dillon 2002, p. 271

- Fantham et al. 1994, pp. 78–79

- Dillon 2002, p. 282

- Dillon 2002, p. 283

- Lyons 2003, p. 96

- Pomeroy 1994, p. 73

- Demosthenes 41.8.

- Lyons 2003, p. 104

- Osborne 1997, p. 20

- Foxhall 1989, p. 34

- Schaps 1975, p. 53

- Schaps 1975, p. 54

- Brock 1994, p. 336

- Brock 1994, pp. 338–339

- Brock 1994, p. 342

- Johnstone 2002, p. 253

- Johnstone 2002

- Johnstone 2002, p. 247

- Pomeroy 1994, pp. 79–80

- Kapparis 1999, p. 5

- Pomeroy 1994, p. 57

- Cantarella 2005, p. 251

- Hamel 2003, pp. 6–7

- Hamel 2003, pp. 12–13

- Fantham et al. 1994, p. 116

- Dover 1973, p. 63

- Kapparis 1999, p. 4

- Kapparis 1999, p. 6

- Hamel 2003, p. 13

- Pomeroy 1994, p. 91

Works cited

- Akrigg, Ben (2015). "Metics in Athens". In Taylor, Claire; Vlassopoulos, Kostas (eds.). Communities and Networks in the Ancient Greek World. Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 9780198726494.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Arthur, Marylin B. (1976). "Classics". Signs. 2 (2): 382–403. doi:10.1086/493365.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Bakewell, Geoffrey (2008). "Forbidding Marriage: "Neaira" 16 and Metic Spouses at Athens". The Classical Journal. 104 (2).CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Beaumont, Lesley A. (2012). Childhood in Ancient Athens: Iconography and Social History. New York: Routledge. ISBN 9780415248747.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Behlman, Lee (2003). "From Ancient to Victorian Cultural Studies: Assessing Foucault". Victorian Poetry. 41 (4): 559–569. doi:10.1353/vp.2004.0001.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Blok, Josine H. (2009). "Perikles' Citizenship Law: A New Perspective". Historia: Zeitschrift für Alte Geschichte. 58 (2).CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Brock, Roger (1994). "The Labour of Women in Classical Athens". The Classical Quarterly. 44 (2): 336–346. doi:10.1017/S0009838800043809.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Burkert, Walter (1992). "Athenian Cults and Festivals". In Lewis, David M.; Boardman, John; Davis, J. K.; et al. (eds.). The Cambridge Ancient History. V (2nd ed.). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 9780521233477.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Cantarella, Eva (2005). "Gender, Sexuality, and Law". In Gagarin, Michael; Cohen, David (eds.). The Cambridge Companion to Greek Law. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 9780521521598.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Carey, Christopher (1995). "Rape and Adultery in Athenian Law". The Classical Quarterly. 45 (2): 407–417. doi:10.1017/S0009838800043482.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Cohen, David (1989). "Seclusion, Separation, and the Status of Women in Classical Athens". Greece & Rome. 36 (1): 3–15. doi:10.1017/S0017383500029284.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Cohn-Haft, Louis (1995). "Divorce in Classical Athens". The Journal of Hellenic Studies. 115: 1–14. doi:10.2307/631640. JSTOR 631640.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Davis, J. K. (1992). "Society and Economy". In Lewis, David M.; Boardman, John; Davis, J. K.; et al. (eds.). The Cambridge Ancient History. V (2nd ed.). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 9780521233477.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Dillon, Matthew (2002). Women and Girls in Classical Greek Religion. New York: Routledge. ISBN 0415202728.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Dover, K. J. (1973). "Classical Greek Attitudes to Sexual Behaviour". Arethusa. 6 (1).CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Engels, Donald (1980). "The Problem of Female Infanticide in the Greco-Roman World". Classical Philology. 75 (2): 112–120. doi:10.1086/366548.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Fantham, Elaine; Foley, Helene Peet; Kampen, Natalie Boymel; Pomeroy, Sarah B.; Shapiro, H. Alan (1994). Women in the Classical World: Image and Text. New York: Oxford University Press. ISBN 9780195067279.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Foxhall, Lin (1989). "Household, Gender, and Property in Classical Athens". The Classical Quarterly. 39 (1): 22–44. doi:10.1017/S0009838800040465.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Foxhall, Lin (2005). "Pandora Unbound: A Feminist Critique of Foucault's History of Sexuality". In Cornwall, Andrea; Lindisfarne, Nancy (eds.). Dislocating Masculinity. London: Routledge. ISBN 0203393430.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Foxhall, Lin (2013). Studying Gender in Classical Antiquity. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 9780521553186.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Gagarin, Michael (2003). "Telling Stories in Athenian Law". Transactions of the American Philological Association. 133 (2): 197–207. doi:10.1353/apa.2003.0015.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Garland, Robert (2013). "Children in Athenian Religion". In Evans Grubbs, Judith; Parkin, Tim (eds.). Oxford Handbook of Childhood and Education in the Classical World. Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 9780199781546.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Golden, Mark (1981). "The Exposure of Girls at Athens". Phoenix. 35. doi:10.2307/1087926. JSTOR 1087926.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Goldhill, Simon (1994). "Representing Democracy: Women at the Great Dionysia". In Osborne, Robin; Hornblower, Simon (eds.). Ritual, Finance, Politics: Athenian Democratic Accounts Presented to David Lewis. Wotton-under-Edge: Clarendon Press. ISBN 9780198149927.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Goldhill, Simon (1997). "The audience of Athenian tragedy". In Easterling, P. E. (ed.). The Cambridge Companion to Greek Tragedy. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 9780521412452.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Gomme, A. W. (1925). "The Position of Women in Athens in the Fifth and Fourth Centuries". Classical Philology. 20 (1): 1–25. doi:10.1086/360628.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Gould, John (1980). "Law, Custom and Myth: Aspects of the Social Position of Women in Classical Athens". The Journal of Hellenic Studies. 100: 38–59. doi:10.2307/630731. JSTOR 630731.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Grossman, Janet Burnett (2007). "Forever Young: An Investigation of Depictions of Children on Classical Attic Funerary Monuments". Hesperia Supplements. 41.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Haley, Shelley P. (1994). "Classical Clichés". The Women's Review of Books. 12 (1): 26. doi:10.2307/4021927. JSTOR 4021927.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Hall, Edith (1994). "Review: Ancient Women". The Classical Review. 44 (2): 367. doi:10.1017/s0009840x00289415.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Hamel, Debra (2003). Trying Neaira: The True Story of a Courtesan's Scandalous Life in Ancient Greece. New Haven & London: Yale University Press. ISBN 9780300107630.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Henderson, Jeffrey (1991). "Women and Athenian Dramatic Festivals". Transactions of the American Philological Association. 121.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Johnstone, Steven (2002). "Apology for the Manuscript of Demosthenes 59.67". The American Journal of Philology. 123 (2).CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Kamen, Deborah (2013). Status in Classical Athens. Princeton: Princeton University Press. ISBN 9780691138138.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Kapparis, Konstantinos A. (1999). "Apollodorus Against Neaira" with commentary. Berlin: Walter de Gruyter. ISBN 9783110163902.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Katz, Marylin (1998a). "Did the Women of Ancient Athens Attend the Theatre in the Eighteenth Century". Classical Philology. 93 (2): 105–124. doi:10.1086/449382.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Katz, Marylin (1998b). "Women, Children, and Men". In Cartledge, Paul (ed.). The Cambridge Illustrated History of Ancient Greece. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 9780521481960.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Katz, Marylin (2000). "Sappho and her Sisters: Women in Ancient Greece". Signs. 25 (2): 505–531. doi:10.1086/495449.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Lewis, Sian (2002). The Athenian Woman: An Iconographic Handbook. London: Routledge. ISBN 9780415232357.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Loraux, Nicole (1993). The Children of Athena: Athenian Ideas about Citizenship and the Division Between the Sexes. Translated by Levine, Caroline. Princeton: Princeton University Press. ISBN 9780691037622.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Lyons, Deborah (2003). "Dangerous Gifts: Ideologies of Marriage and Exchange in Ancient Greece". Classical Antiquity. 22 (1).CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Lysias (1930). Lysias. Translated by Lamb, W. R. M. Cambridge: Harvard University Press. ISBN 9780674992696.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Milnor, Kristina (2000). "Review: Rethinking Sexuality". The Classical World. 93 (3).CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Noy, David (2009). "Neaera's Daughter: A Case of Athenian Identity Theft?". The Classical Quarterly. 59 (2): 398–410. doi:10.1017/S0009838809990073.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Oakley, John H. (2013). "Children in Archaic and Classical Greek Art: A Survey". In Evans Grubbs, Judith; Parkin, Tim (eds.). Oxford Handbook of Childhood and Education in the Classical World. Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 9780199781546.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Osborne, Robin (1997). "Law, the Democratic Citizen, and the Representation of Women in Classical Athens". Past & Present. 155: 3–33. doi:10.1093/past/155.1.3.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Patterson, Cynthia B. (1985). ""Not Worth the Rearing": The Causes of Infant Exposure in Ancient Greece". Transactions of the American Philological Association. 115.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Patterson, Cynthia (1987). "Hai Attikai: The Other Athenians". In Skinner, Marylin B. (ed.). Rescuing Creusa: New Methodological Approaches to Women in Antiquity. Lubbock, Texas: Texas Tech University Press. ISBN 9780896721494.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Patterson, Cynthia (2007). "Other Sorts: Slaves, Foreigners, and Women in Periclean Athens". In Sammons, Loren J., II (ed.). The Cambridge Companion to the Age of Pericles. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 9780521807937.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Pomeroy, Sarah B. (1994). Goddesses, Whores, Wives, and Slaves: Women in Classical Antiquity. London: Pimlico. ISBN 9780712660549.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Pomeroy, Sarah B. (2002). Spartan Women. Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 9780195130676.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Rhodes, P. J. (1992). "The Athenian Revolution". In Lewis, David M.; Boardman, John; Davis, J. K.; et al. (eds.). The Cambridge Ancient History. V (2nd ed.). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 9780521233477.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Roselli, David Kawalko (2011). Theater of the People: Spectators and Society in Ancient Athens. Austin: University of Texas Press. ISBN 9780292744776.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Roy, J. (1999). "'Polis' and 'Oikos' in Classical Athens". Greece & Rome. 46 (1): 1–18. doi:10.1017/S0017383500026036.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Schaps, D. M. (1975). "Women in Greek Inheritance Law". The Classical Quarterly. 25 (1): 53–57. doi:10.1017/S0009838800032894.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Schaps, D. M. (1977). "The Woman Least Mentioned: Etiquette and Women's Names". The Classical Quarterly. 27 (2): 323–330. doi:10.1017/S0009838800035606.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Schaps, D. M. (1998). "What Was Free about a Free Athenian Woman?". Transactions of the American Philological Society. 128.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Vlassopoulos, Kostas (2007). "Free Spaces: Identity, Experience, and Democracy in Classical Athens". The Classical Quarterly. 57 (1): 33–52. doi:10.1017/S0009838807000031.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Walters, K. R. (1983). "Perikles' Citizenship Law". Classical Antiquity. 2 (2): 314–336. doi:10.2307/25010801. JSTOR 25010801.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Winkler, John J. (1989). The Constraints of Desire: the Anthropology of Sex and Gender in Ancient Greece. New York: Routledge. ISBN 9780415901239.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

External links

![]()