Second Hellenic Republic

The Second Hellenic Republic is a modern historiographical term used to refer to the Greek state during a period of republican governance between 1924 and 1935. To its contemporaries it was known officially as the Hellenic Republic (Greek: Ἑλληνικὴ Δημοκρατία, [eliniˈci ðimokraˈtia]) or more commonly as Greece (Greek: Ἑλλάς, [eˈlas], Hellas). It occupied virtually the coterminous territory of modern Greece (with the exception of the Dodecanese) and bordered Albania, Yugoslavia, Bulgaria, Turkey and the Italian Aegean Islands. The term Second Republic is used to differentiate it from the First and Third republics.

Hellenic Republic Ἑλληνικὴ Δημοκρατία | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1924–1935 | |||||||||

.svg.png) The Hellenic Republic in 1930 | |||||||||

| Capital | Athens | ||||||||

| Common languages | Greek (Katharevousa had official status, while Demotic was popular) | ||||||||

| Religion | Eastern Orthodox Church | ||||||||

| Government | Parliamentary republic[1] | ||||||||

| President | |||||||||

• 1924–1926 | Pavlos Kountouriotis | ||||||||

• 1926 | Theodoros Pangalos | ||||||||

• 1926–1929 | Pavlos Kountouriotis | ||||||||

• 1929–1935 | Alexandros Zaimis | ||||||||

| Prime Minister | |||||||||

• 1924 (first) | Alexandros Papanastasiou | ||||||||

• 1933–1935 (last) | Panagis Tsaldaris | ||||||||

| Legislature | Parliament | ||||||||

• Upper house | Senate | ||||||||

• Lower house | Chamber of Deputies | ||||||||

| Historical era | Interwar period | ||||||||

• Established | 25 March 1924 | ||||||||

• Abolished | 3 November 1935 | ||||||||

| Area | |||||||||

| 130,199 km2 (50,270 sq mi) | |||||||||

| Population | |||||||||

• 1924 | 5,924,000[2] | ||||||||

• 1928 (census) | 6,204,684[2] | ||||||||

• 1935 | 6,839,000[2] | ||||||||

| Currency | Greek drachma | ||||||||

| |||||||||

| Today part of | |||||||||

The fall of the monarchy was proclaimed by the country's parliament on 25 March 1924.[1] A relatively small country with a population of 6.2 million in 1928, it covered a total area of 130,199 km2 (50,270 sq mi). Over its eleven-year history, the Second Republic saw some of the most important historical events in modern Greek history emerge; from Greece's first military dictatorship, to the short-lived democratic form of governance that followed, the normalisation of Greco-Turkish relations which lasted until the 1950s, and to the first successful efforts to significantly industrialise the nation.

The Second Hellenic Republic was abolished on 10 October 1935,[3] and its abolition was confirmed by referendum on 3 November of the same year which is widely accepted as having been mired with electoral fraud. The fall of the Republic eventually paved the way for Greece to become a totalitarian single-party state, when Ioannis Metaxas established the 4th of August Regime in 1936, lasting until the Axis occupation of Greece in 1941.

Part of a series on the |

|---|

| History of Greece |

|

|

|

|

History by topic |

|

|

Name

When the Republic was proclaimed on 25 March 1924, the official name adopted for the country was Hellenic State (Greek: Ἑλληνικὴ Πολιτεία).[1] However, the name was changed to Hellenic Republic (Greek: Ἑλληνικὴ Δημοκρατία) on 24 May 1924 by vote of the Parliament.[4] Accordingly, the title of the country's head of state was changed from Governor (Greek: Κυβερνήτης) to President of the Republic (Greek: Πρόεδρος της Δημοκρατίας).[4] The word Δημοκρατία (dimokratía), used in the official name to mean Republic, translates as "democracy" as well.[5]

In everyday speech the country was simply known as Greece. In the official variant of Greek that was the language of state, known as Katharevousa, this was Ἑλλάς (Ellás). In Demotic, or 'popular Greek', it was Ἑλλάδα (Elláda). Sometimes, the name Hellas was used in English as well.

History

National Schism and the republican question

The collapse of the Hellenic Army in Asia Minor was quickly followed by the collapse of the government. Public outrage at the Asia Minor disaster, as Greece's defeat in the war became known, was partially reflected in the military coup which followed it. The coup, orchestrated by army officers, took the name The Revolution. Although The Revolution itself did not abolish the monarchy, one of its first acts was to shut down all the royalist newspapers as well as use the Armed Forces to prosecute known royalists (including Ioannis Metaxas, who was forced to flee abroad).[6] The decision whether or not to abolish the monarchy is one which divided Greek society, as even some Liberal Party supporters, including the Party's founder, Eleftherios Venizelos, spoke out in favour of retaining the monarchy as a safety net against instability.[7]

After the defeat of Greece by the Turkish National Movement (the "Asia Minor Catastrophe") of 1922, the defeated army revolted against the royal government. Under Venizelist officers like Nikolaos Plastiras and Stylianos Gonatas, King Constantine I was again forced to abdicate, and died in exile in 1923. His eldest son and successor, King George II, was soon after asked by the parliament to leave Greece so the nation could decide what form of government it should adopt. In a 1924 plebiscite, Greeks voted to create a republic. These events marked the culmination of a process that had begun in 1915 between King Constantine and his political nemesis, Eleftherios Venizelos.

First years

The Republic was proclaimed on 25 March 1924 by the Parliament;[1] the chosen date was very significant as the Greek War of Independence is traditionally celebrated on 25 March. Following the proclamation of the change in form of government from constitutional monarchy (βασιλευομένη δημοκρατία, literally crowned republic) to republic (αβασίλευτη δημοκρατία, literally uncrowned republic), a referendum was held proclaimed for 13 April 1924.[9] Voters were asked whether they "approve of the decision of the National Assembly that Greece be reorganised into a Republic on the parliamentary model".[9] Voting was to be secret, although the requirement that "yes" votes be cast with white ballots and "no" votes with yellow ones[9] defeated the purpose of secrecy.

The results of the referendum were a clear victory for the Republican campaign: 69.9% in favour of a republic and 30.1% in favour of the monarchy;[8] these results were almost identical to the results of the 1974 referendum (69.2% in favour, 30.8% against) which finally abolished the monarchy.[8] Newspapers from a wide range of the political spectrum noted a lack of violence, implying a lack of electoral intimidation in favour of one side or another. The newspaper Forward wrote that the vote was "historic for the order which prevailed during the voting time",[10] Skrip commented that people refrained from "any action which could be seen as a provocation" and that "the military measures [taken] made this easier",[11] while the Communist Party's Rizospastis commented on the "relative calm" that prevailed in the electoral district of Athens.[12] Makedonia added that so many people disregarded the yellow "no" ballots, that the floors inside the electoral centers and the streets around were littered with them.[13] Meanwhile, the decree of 1924 "on the safeguard of the republican regime" introduced the jail sentence for a minimum of six months for advocating in public the return of the monarchy, disputing the results of the referendum or publishing slander against the founders of the republic.[14] In an interview following the referendum, then-Prime Minister Alexandros Papanastasiou defended government plans to pass such a decree, saying that the government must be allowed to move forward with its reforms without any sort of hindrance for a limited amount of time.[11]

The fragile nature of the young Greek republic became evident from the first year of its existence. While the Parliament was still debating the new constitution (see below), General Theodoros Pangalos organised a coup. When asked by the Minister of the Military whether he was planning to overthrow the government, Pangalos replied "of course I will carry out a coup".[15] His plot was set to motion on 24 June 1925, and soon prevailed throughout the country with little or no resistance from government forces.[15]

Following his coup, Pangalos was sworn in as Prime Minister by the acting Governor of Greece (Pavlos Kountouriotis) and demanded that the Parliament give him a vote of confidence. Surprisingly, he received the vote of confidence with 185 of the 208 Members of Parliament present voting in favour, including Alexandros Papanastasiou (the Prime Minister before Pangalos' coup) and Georgios Kondylis.[15]

Meanwhile, relations between Bulgaria and Greece were cold, and this escalated into a full-blown conflict by October 1925. A clash along the Greco-Bulgarian border on 18 October led to the Pangalos dictatorship ordering the III Army Corps to invade Bulgaria.[15] Bulgaria, being unable to defend itself sufficiently, and with the Greek army on the outskirts of Petrich, turned to the League of Nations.[15] Eventually, the League of Nations condemned the Greek invasion and ordered Greece to pay £47,000 (£2.7 million in 2017)[16] to Bulgaria as compensation.[17] Greece complied with the ruling and withdraw from Bulgaria, but not before 50 people had lost their lives in the short conflict. Further, Greece protested at the double standards that existed for dealing with such incidents, ones for small countries and ones for Great Powers like Italy, which occupied Corfu in the Corfu Incident just two years prior.[18] Moreover, there was a growing democratic deficit in Greece between liberal democracy as enshrined in the Constitution, and as implemented in practice; over 1,000 political activists, mostly communists were exiled to remote Aegean islands under the Pangalos dictatorship, and the situation did not improve after his fall.[19] A new law targeting trade union activism was passed in 1929, commonly known as the Idionymon, and some 16,000 activists were brought before criminal procedures in the period 1929–1936, with 3,000 exiled to remote islands.[19]

Later years and collapse

Kountouriotis was reinstated and reelected to the office in 1929, but was forced to resign for health reasons later that year. He was succeeded by Alexandros Zaimis, who served until the restoration of the monarchy in 1935.

Despite a period of stability and sense of well-being under the government of Eleftherios Venizelos on 4 July 1928 – 6 March 1933, the effects of the Great Depression were severely felt, and political instability returned. As the prospect of the return of the monarchy became more likely, Venizelist officers launched a coup in March 1935, which was suppressed by General Georgios Kondylis. On October 10, 1935, the chiefs of the Armed Forces overthrew the government of Panagis Tsaldaris and forced President Zaimis to appoint Kondylis prime minister in his place. Later that day, Kondylis forced Zaimis himself to resign, declared himself regent and abolished the republic. A heavily rigged plebiscite occurred on 3 November which resulted in an implausible 98% supporting the return of the monarchy. King George II returned to Athens on 23 November, with Kondylis as prime minister.

Politics

Law and order

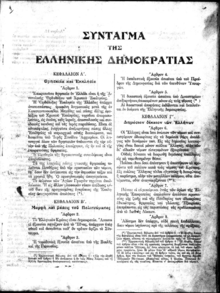

The Constitution of 1927 is considered a progressive one for its time. Written to replace the Constitution of 1926, which was never implemented, it was passed in the parliament on 3 June 1927. The most profound change brought upon the country by the passing of the new constitution was the overthrow of the monarchy on a de jure level (the monarchy had been de facto abolished in the referendum of 1924). Article 2 established a republic (the word used in the constitution is "Δημοκρατία", which can mean both democracy and republic).[20]

Various other civil and political rights were established in the Constitution. Article 6 established complete equality of Greek citizens before the law and abolished titles of nobility.[21] Article 7 guaranteed the "absolute protection of the life and freedom" of all persons in Greece regardless of nationality, religion or language.[21] Article 8 forbade the creation of ex post facto laws.[21] Article 10 established personal freedom as "absolutely inviolable".[21] Article 11 forbade arrest without a warrant.[21] Articles 13 and 14 established freedom of assembly and freedom of association respectively.[21] Article 15 established the sanctity of a person's house and forbade entry or search within a person's house without a warrant.[21] Article 16 established freedom of the press.[21] Article 17 forbade torture and public execution, and forbade executions for civil or political crimes.[21] Article 18 established the privacy of letters, telegrams and telephone conversations as "absolutely inviolable".[21] Article 19 established the right to property.[21] Further, Articles 21 and 22 established artistic, academic and educational freedom and the right to intellectual property respectively.[21] Finally, Article 25 established the right to petition.[21]

Overall, the constitution included 127 articles which outlined the various organs of the state and how these functioned. Article 125 forbade the amendment of the constitution for the first 5 years of its implementation, and further forbade the amendment of the "fundamental" articles of the constitution thereafter.[22] Article 127 made the Greek nation responsible for the implementation of the constitution.[22] In effect, this gave "the Nation" supremacy over the country's politicians and/or parliament with regards to constitutionality and gave "the Nation" power to overturn laws deemed unconstitutional.

Parliament and franchise

The constitution of 1927 established a bicameral legislature. The two houses were the Vouli (Greek: Βουλή, [vuˈli]) and the Senate (Greek: Γερουσία, [ʝeruˈsia]).[23] Further, the constitution outlines the duties of the two houses and the number of parliamentarians. The lower house was to be made up of between 200 and 250 members elected in their constituency for four-year terms.[23] The Senate had a more complex composition; Article 58 states that it is made up of 120 senators of which 92 were directly or indirectly elected by the people, 10 were elected by a joint session of the Vouli and the Senate and 18 were elected by 8 unions representing various vocations including merchants (1), industrialists (3), workers (5) and academics (1).[23][24] Of the 92 senators directly or indirectly elected by the people, 90 were allocated to parliamentary constituencies of varying size for direct election and two were given to ethnic minorities for election through an electoral college: 1 for the Turks of Western Thrace and 1 for the Jews of Thessaloniki.[24] Each senator served a nine-year term, while the composition of the Senate was renewed by 1/3 every three years.[23] The salaries of members of parliament in both houses were the same.[23]

Between 1924 and 1935, a total of six elections took place. The politics of the Second Republic were dominated by the republican Liberal Party, under the leadership of Eleftherios Venizelos, and the moderately conservative-monarchist People's Party under Panagis Tsaldaris. These parties were the primary means by which Greeks participated in the political life and they were not parties built on principles or class consciousness, but rather "parties of personalities" relying on charismatic leaders around which the base coalesced.[25] The traditional Greek café was the battleground for everyday political discussions, and the high degree of personal involvement in political discussions set Greece apart from other constitutional countries.[25] This created both positive and negative side effects; on the one hand the population was politically involved on a personal level, and therefore incentivised, but on the other this political involvement made the country highly critical.[25]

In 1930, after five years of deliberation, suffrage was partially extended to women, who were now allowed the right to vote, but not stand for election, in local elections.[26] The first opportunity to do so was given to them in the same year in Thessaloniki, where 240 women exercised their right.[26] Nationwide the turnout of women remained low, with only approximately 15,000 participating in the local elections of 1934.[26] The inclusion of women as candidates for election in numerous electoral lists was struck down by the courts with the argument that the law had only given women "a limited franchise".[26] The table below illustrates the performance of the two major political parties in the parliamentary and senate elections that took place under the Second Republic.

| Election | Lower house (Vouli) | Upper house (Senate) | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Liberal Party | People's Party | Others | Liberal Party | People's Party | Others | ||||||||

| % | Seats | % | Seats | % | Seats | % | Seats | % | Seats | % | Seats | ||

| 1926[27] | 31.6% | 102 | 20.3% | 60 | 48.1% | 117 | NA | ||||||

| 1928[27] | 46.9% | 178 | 23.9% | 19 | 29.2% | 53 | NA | ||||||

| 1929[24] | NA | 54.6% | 64 | 19.1% | 10 | 26.3% | 21 | ||||||

| 1932[27] | 33.4% | 98 | 33.8% | 95 | 32.8% | 57 | 39.5% | 16 | 32.5% | 13 | 28.0% | 1 | |

| 1933[27] | 33.3% | 80 | 38.1% | 118 | 28.6% | 50 | NA | ||||||

| 1935[24] | boycott | 65.0% | 254 | 35.0% | 46 | NA | |||||||

Foreign relations

The Republic's foreign policy was largely shaped by the Premiership of Eleftherios Venizelos. Before his re-ascention to power in the 1928 legislative elections, Greece was faced with significant obstacles in its foreign policy: growing claims by Yugoslavia on Thessaloniki, bad relations with Bulgaria and Turkey, while relations with the Great Powers were at their lowest point since Greece was established in 1832.[28] In co-operation with Mustafa Kemal Atatürk, as well as İsmet İnönü's government, a series of treaties were signed between Greece and Turkey in 1930 which, in effect, restored Greek-Turkish relations and established a de facto alliance between the two countries.[29] As part of these treaties, Greece and Turkey agreed that the Treaty of Lausanne would be the final settlement of their respective borders, while they also pledged that they would not join opposing military or economic alliances and to stop immediately their naval arms race.[29] The good relations established by the Republic would last until the 1950s.

In 1934, the government of Panagis Tsaldaris signed, in Athens, the Balkan Pact (or Balkan Entente), a military alliance between Greece, Romania, Turkey and Yugoslavia, which further improved the Republic's relations with its Balkan neighbours, although the exclusion of Bulgaria and Albania left some matters unsettled.[30] Eventually, however, Great Power politics derailed the Pact, which never brought the desired results.[30]

Apart from an interest in regional stability and friendship, the Second Republic, through Venizelos, supported early initiatives for the creation of a European Union. In October 1929, as Prime Minister, Venizelos gave a speech outlining his government's support for Aristide Briand's efforts on the matter, saying that "the United States of Europe will represent, even without Russia, a power strong enough to advance, up to a satisfactory point, the prosperity of the other continents as well".[28]

Regions

.svg.png)

The Second Hellenic Republic was subdivided into 10 regions, which we would today call the traditional geographic regions of Greece. These varied widely in size and population. The most populous was Central Greece and Euboea, with 1.6 million people, followed closely by Macedonia (1.4 million), while the smallest were the Cyclades with 129,702 people. The largest in total area was Macedonia at 34,892.8 km2 (13,472.2 sq mi), while the smallest were the Ionian Islands, at 1,921.5 km2 (741.9 sq mi). The Ionian Islands were also Greece's most densely populated region, with a population density of 110.93/km2 (287.3/sq mi).

| Region | Capital | Population | Area | Density | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| in km2 | in sq mi | per km2 | per sq mi | ||||

| 1 | Central Greece and Euboea | Athens | 1,592,842 | 24,995.8 | 9,650.9 | 63.72 | 165.0 |

| 2 | Macedonia | Thessaloniki | 1,412,477 | 34,892.8 | 13,472.2 | 40.48 | 104.8 |

| 3 | Peloponnese | Tripolis | 1,053,327 | 22,282.8 | 8,603.4 | 47.27 | 122.4 |

| 4 | Thessaly | Larissa | 493,213 | 13,334.4 | 5,148.4 | 36.99 | 95.8 |

| 5 | Crete | Chania | 386,427 | 8,286.7 | 3,199.5 | 46.63 | 120.8 |

| 6 | Epirus | Ioannina | 312,634 | 9,351.0 | 3,610.4 | 33.43 | 86.6 |

| 7 | Aegean Islands | Mytilene | 307,734 | 3,847.9 | 1,485.7 | 79.97 | 207.1 |

| 8 | Western Thrace | Komotini | 303,171 | 8,706.3 | 3,361.5 | 47.66 | 123.4 |

| 9 | Ionian Islands | Corfu | 213,157 | 1,921.5 | 741.9 | 110.93 | 287.3 |

| 10 | Cyclades | Ermoupolis | 129,702 | 2,580.2 | 996.2 | 50.27 | 130.2 |

| - | Greece | Athens | 6,204,684 | 130,199.4 | 50,270.3 | 47.66 | 123.4 |

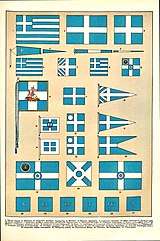

Flags and symbols

For most of its history, Greece had two distinct national flags which co-existed: a simple blue field with a white cross for use as a national flag on land, and a more complex design featuring nine blue and white stripes with a white cross on a blue field in the canton, for use on ships (ensign) and on land when displayed abroad.[32] Those flags were first adopted in 1822 during the Greek War of Independence.[33] With the collapse of the monarchy and the creation of the Second Republic, all national symbols of Greece were modified to reflect a change to republican rule. The flags in particular saw the removal of the crowns,[34] which had been placed in the middle of the white cross since 1863, while the national emblem was stripped of its mantle and pavilion, as well as its supporters, down to a simple escutcheon bearing a Greek cross. The blue and white colours were thought to symbolise the colour of the sky and the waves.[34]

During the short-lived dictatorship of Theodoros Pangalos four symbols were added to the national emblem in the four quarters created by the cross: the head of Athena, symbolising the ancient Greek period; a helmet and spear, symbolising the Hellenistic period; a double-headed eagle, symbolising the Byzantine period; and a Phoenix rising from its ashes, symbolising the modern Greek period.[34] A wreath of oak and laurel surrounded the emblem, symbolising power and glory respectively.[34] This particular emblem was criticised for being inappropriate and violating heraldic rules before being replaced by the simple shield following the fall of Pangalos' dictatorship.[34]

Military and police

The peacetime organisation of the Hellenic Army in 1930 was made up of 10 Divisions organised in 4 Corps, with two of the divisions being independent, while an additional brigade was stationed in the Archipelago.[35] The organisation of the Army differed from its wartime composition; not all divisions had artillery support units during peacetime, for example.[35] In 1933 the Hellenic Navy was made up of 2 battleships (Kilkis and Lemnos; both docked permanently), 1 armoured cruiser (Georgios Averof), 1 cruiser (Elli), 12 destroyers, 9 torpedo boats, 6 submarines, 2 fast attack craft, and 9 auxiliary support vessels.[36] A Ministry of Aviation was established in 1930 to consolidate the Air Force, and in 1933 the Hellenic Air Force was made up of 5 air bases, each with 2 squadrons (usually), and utilised Breguet 19, Potez 25, Hawker Horsley, Greek-built Velos, and Fairey III planes.[37] Military expenditures accounted for ₯2.04 billion in 1935; 18.8% of total government expenditures.[38]

Law enforcement was handled by a series of different bodies, including the Hellenic Gendarmerie (Χωροφυλακή), the Cities Police (Ἀστυνομία Πόλεων), the Countryside Police (Ἀγροφυλακή), and the Forests Police (Δασοφυλακή).

Economy

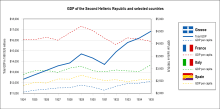

According to the University of Groningen's Maddison Project, Greece's GDP in 1924 stood at $23.72 billion (in 2011 value; $27 billion in today's value).[40] Economic growth between 1924 and 1935 stood at an average of 2.96%.[40] Broken down, between 1924 and 1929 growth stood at 3.52%, during the Great Depression at –3.23%, and between 1932 and 1935 at an average of 5.24%.[40] By 1935 GDP had risen to $32.41 billion (in 2011 value; $37 billion in today's value).[40] GDP per capita stood at $3,957 in 1924 and $4,771 by the end of the republic in 1935, putting Greece in a comparable position to Spain and much better off than its neighbours.[40] Contemporaneous accounts put the gross national income during the Great Depression at ₯41 billion in 1929, ₯37 billion in 1930 (down 10%), and ₯30 billion in 1931 (down 30%).[41]

The labour force in the Census of 1928 is shown as overwhelmingly agricultural and male-dominated.[39] Unemployment among men stood at 16.8% according to the census of 1928 while 68% of women stated they did not work.[39] Trade unionism, though legal, was actively discouraged by the government and some 3,000 labour activists were sent to internal exile in the period 1929–1936.[19]

Public finances

The complexity of the tax code of the era made it difficult to determine the average tax rate imposed on income, however the Great Greek Encyclopedia notes that the tax burden in Greece was the highest in the Balkans, approaching the levels seen in wealthy western European nations, bringing in the estimated equivalent of 25.66% of total gross national income in tax revenue in 1932–1933.[41] Property tax ranged from 4% to 11%, but with the addition of further taxes could reach over 27%, while salaries were taxed at rates between 6% and 21%.[42] Certain commodities were heavily taxed, including sugar (269.0%), coffee (91.7%), tea (79.3%), and wheat (80.79%) among others.[41] Additionally, certain industries were state monopolies whose proceeds went to financing the national debt. These encompassed the production of salt, petrol, matches, playing cards, rolling paper, saccharin (artificial sugar), and narcotics.[39] Together these industries contributed ₯742 million to the economy in 1934 alone (8% of total revenues).[39]

| 1923 | 1924 | 1925 | 1926 | 1927 | 1928 | 1929 | 1930b | 1931b | 1932 | 1933 | 1934 | 1935 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Revenue (in ₯ millions) | 3,984 | 5,723 | 7,922 | 9,508 | 8,996 | 10,551 | 18,729 | 11,394 | 11,076 | 9,144 | 8,468 | 9,237 | 10,647 |

| Expenses (in ₯ millions) | 5,000 | 5,498 | 6,841 | 8,687 | 7,770 | 9,446 | 18,355 | 11,176 | 11,099 | 9,117 | 7,706 | 8,746 | 10,049 |

| Surplus or deficit (in ₯ millions)a | -1,016 | +225 | +1,081 | +821 | +1,226 | +1,105 | +374 | +217 | -22 | +27 | +762 | +491 | +597 |

| Public debt (in ₯ millions)[45][46][47][39][44] | 35,762 | 38,169 | 38,559 | 41,279 | 42,967 | 43,143 | 42,965 | 44,985 | |||||

| a Before debt repayments are factored in b The Great Depression | |||||||||||||

Trade and commerce

_ki%C3%A1ll%C3%ADt%C3%A1si_ter%C3%BClete._Fortepan_93026.jpg)

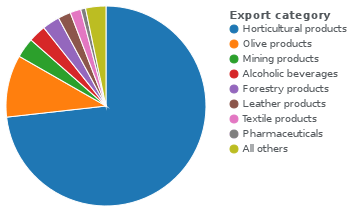

The agricultural nature of Greece's economy was reflected in its exports. In 1933 over 85% of Greece's exports in terms of value were agricultural, with the largest share of exports being raw tobacco (₯738 million).[49] The Great Depression had a big impact on the prices of luxury products such as tobacco and raisins, which were the bulk of Greece's agricultural exports, and the collapse of prices hit exports such as tobacco hard. While in 1933 the country exported 34,743 tons of tobacco worth ₯738 million (₯20,000 per ton), it exported 50,055 tons worth ₯3.95 billion (₯80,000 per ton) before the crisis.[49]

Governments during the Second Republic enacted numerous protectionist policies aimed at reducing Greece's negative balance of trade by £7 million (£446 million in today's value), something which was ultimately achieved and greatly benefited the domestic industrial economy.[49] When the Republic was established, more than two thirds of the country's wheat requirement had to be imported from abroad; by the fall of the Republic this had reverted and Greece was practically self-sustaining in terms of wheat thanks to tariffs established by the government and incentives given for the cultivation of wheat.[50] Ultimately however falling prices during the Great Depression had a bigger impact in improving the trading position of the country than protectionist policies did.[49]

There were three free economic zones in the country, the Port of Thessaloniki (established 1914), the Port of Piraeus (established 1930), and the Serbian free port contained within the Port of Thessaloniki (imposed on Greece by the Treaty of Bucharest in 1913).[51] Trends at the Port of Thessaloniki show a big decline in imports between 1926 and 1933, from 69,013 m3 (2,437,200 cu ft) to 14,223 m3 (502,300 cu ft), and a large increase in exports during the same period, from 178 m3 (6,300 cu ft) to 41,322 m3 (1,459,300 cu ft), peaking at 70,605 m3 (2,493,400 cu ft) in 1927.[51] The annual Thessaloniki International Fair was also inaugurated in 1927, with over 1,600 participating companies from numerous countries in 1933, and great economic benefit to Northern Greece.[52]

| By import value (in thousands) | Balance (₯) | By export value (in thousands) | Balance (₯) | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Country | Imports (₯) | Exports (₯) | Country | Exports (₯) | Imports (₯) | |||||

| 1 | 1,996,627 | 2,109,368 | +112,741 | 1 | 2,109,368 | 1,996,627 | +112,741 | |||

| – | 1,957,369 | 901,906 | -1,055,463 | 2 | 1,202,475 | 667,332 | +535,143 | |||

| 2 | 1,657,897 | 897,999 | -759,898 | – | 901,906 | 1,957,369 | -1,055,463 | |||

| 3 | 1,056,371 | 60,107 | -996,264 | 3 | 897,999 | 1,657,897 | -759,898 | |||

| 4 | 795,903 | 230,764 | -565,139 | 4 | 422,555 | 393,981 | +28,574 | |||

| 5 | 667,332 | 1,202,475 | +535,143 | 5 | 292,518 | 312,897 | -20,379 | |||

| 6 | 486,921 | 70,952 | -415,971 | 6 | 275,330 | 268,208 | +7,122 | |||

| 7 | 413,087 | 188,046 | -225,041 | 7 | 230,764 | 795,903 | -565,139 | |||

| 8 | 409,013 | 153,733 | -255,280 | 8 | 213,560 | 217,209 | -3,649 | |||

| 9 | 393,981 | 422,555 | +28,574 | 9 | 194,984 | 184,151 | +10,833 | |||

| 10 | 312,897 | 292,518 | -20,379 | 10 | 188,046 | 413,087 | -225,041 | |||

| – | Other nations | 533,990 | 570,886 | -36,876 | – | Other nations | 1,073,690 | 3,774,096 | -2,700,406 | |

| Total trade | 10,681,388 | 7,101,289 | -3,580,099 | Total trade | 7,101,289 | 10,681,388 | -3,580,099 | |||

Bank reforms and industrialisation

In the early years of the Republic, the government of Alexandros Zaimis took a loan from British banks that totalled £9 million (£541 million in today's value) intended for land reclamation and improvement (primarily in the northern regions).[50] The conditions for this loan, however, stipulated that Greece had to stabilise its currency (the Greek drachma) by adopting the gold standard and by establishing a central bank to oversee economic policy.[50] A further loan for £4 million (£243 million in today's value) in order to carry out public works was taken in 1928.[54] In May 1928 the Bank of Greece was established, revoking the National Bank of Greece's rights to print currency much to the dissatisfaction of the NBG.[50] A similar dispute erupted again in 1929, when the Greek government decided to establish the Agricultural Bank of Greece and revoke the NBG's rights to give out agricultural loans.[50]

The reforms brought about by the government changed the face of the Greek banking sector, and although the Agricultural Bank sustained the Greek rural economy through two years of hardship between 1931 and 1932 by issuing loans totalling ₯1.3 billion, the National Bank of Greece dominated the industrial and manufacturing sectors.[50]

One of the main electoral promises made by Venizelos during his campaign for the Premiership in 1928 was to change the face of Greece in four years by funding large-scale infrastructure projects aimed at increasing production.[50] This was largely achieved by his government, and between 1929 and 1938 Greece had industrial growth rates that averaged between 5.11% and 5.73%, ranking the country third in the world behind Japan and the Soviet Union.[50] By 1926, Greece's light industry supplied 76.4% of the country's demand, while heavy industry was almost non-existent.[55] Between 1923 and 1932 the Greek government borrowed ₯950 million which was channelled to infrustructural projects, while another ₯600 million was lent to private enterprises.[50] Overall successive governments under the Second Republic borrowed over ₯6.6 billion from within the country in the period 1924–1929, either through loans with Greek banks or through the forced exchange of banknotes for interest-gaining floating rate notes.[54]

As of 1933 there were 30 banks in the country, 5 of which were foreign banks.[56] The total capitalisation of the banking sector stood at ₯3.49 billion in the same year; the same banks held ₯18.84 billion in deposits.[56]

| 1924 | 1925 | 1926 | 1927 | 1928 | 1929 | 1930† | 1931† | 1932 | 1933 | 1934 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Patents | 248 | 299 | 301 | 391 | 383 | 502 | 574 | 513 | 510 | 506 | 565 |

| Trademark registrations | 809 | 655 | 602 | 686 | 1,050 | 1,060 | 1,191 | 960 | 1,018 | 2,326 | 1,565 |

| New factories opened | 107 | 132 | 124 | 214 | 192 | 63 | 45 | 93 | 50 | 37 | 67 |

| Electricity production (kW h) | 40,000 | 40,000 | 50,000 | 60,000 | 70,000 | 100,000 | 115,000 | 120,000 | 125,000 | 140,000 | |

| Total industrial production (in ₯ millions) | 3,883 | 4,978 | 5,473 | 6,655 | 7,115 | 7,158 | 6,631 | 6,052 | 6,749 | 8,548 | 9,913 |

| Yearly industrial growth | +21.7% | +28.2% | +9.9% | +21.6% | +6.9% | +0.6% | -7.4% | -8.7% | +11.5% | +26.7% | +16.0% |

| † The Great Depression | |||||||||||

Greece during the Great Depression

Eleftherios Venizelos in the Hellenic Parliament, March 1932[58]

In 1928 the Venizelos government had a number of economic concerns to worry about, however the government budget and general economic situation gave some hope. Between 1928 and 1931 three consecutive budgets had shown a surplus, unemployment was kept at a safe level and the national debt was reduced by 11%.[50] On 21 September 1931 however the United Kingdom abandoned the gold standard and the crisis hit Greece. By 27 September 1931 the run on the banks had caused the Bank of Greece to lose $3.6 million of its foreign reserves ($61 million in today's value).[50]

The following couple of years were grim for the Greek economy as it entered recession along with the rest of the global economy. In early 1932 Venizelos asked the League of Nations for a loan of $50 million ($937 million in today's value) in order to help the Greek economy, but the loan was denied. Faced with insolvency, Greece abandoned the gold standard and defaulted on its debts on 25 April 1932. The Greek drachma was devalued by 62% against the dollar, foreign trade contracted by 61.5% compared to 1929 and tobacco production was reduced by 81.0%.[50] However, the Venizelos government's policies secured a steady flow of credit for the Bank of Greece and thus averted a collapse of the banking system, which had occurred in most other European countries as well as the United States.[50] Nevertheless, Greece declared bankruptcy for the fourth time in its history in 1932, ceasing to make payments on its international loans, some of which dated as far back as the 1820s.[54] A compromise with the country's lenders was reached in 1935 and payments resumed thereafter until being suspended again with the outbreak of the Second World War.[54] Capital controls were also implemented in that period.[49]

Currency and circulation

.png)

Under the Second Republic, the Greek drachma (sign: ₯, Δρ or Δρχ) continued to exist as the national currency. As part of the government's efforts to reform the banking system (see above), the Bank of Greece was established in 1928. Following this move, Greece's largest commercial bank, the National Bank of Greece, could no longer print currency. In addition, Greece joined the gold standard on 14 May 1928 and the Drachma was de facto stabilised at an exchange rate of £1 to ₯375 ±₯2.5.[59] This put an end to the spiralling devaluation of the Drachma, whose exchange rate to the Pound had dropped from ₯25 per £1 in 1919 to ₯309 in 1924 and slightly up to ₯247 in 1927.[60] The value of currency in circulation steadily increased during the Second Republic, reaching ₯5.6 billion in 1935.[61] The first series of Banknotes issued by the Bank of Greece was also introduced in 1935, with colourful banknotes of ₯50, ₯100, and ₯1,000 printed in France.[62]

When Britain abandoned the Gold Standard on 21 September 1931, Greece did not follow suit. Instead, the Drachma remained in the Gold Standard but switched pegging from the Pound to the US dollar.[59] Despite this move, the Drachma had already been under pressure and the convertibility was suspended in April 1932, when the Drachma was devalued and Greece left the Gold Standard.[59] Following its devaluation, the Drachma was the second least-valued currency in Europe, marginally beating the Romanian leu.[63] For the rest of the Second Republic, Greece showed interest in joining the Gold bloc.[59]

| 1924 | 1925 | 1926 | 1927 | 1928 | 1929 | 1930 | 1931 | 1932 | 1933 | 1934 | 1935 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Carats of gold per ₯1 | 1.79 | 1.56 | 1.26 | 1.31 | 1.30 | 1.30 | 1.30 | 1.30 | 0.83 | 0.56 | 0.56 | 0.56 |

| Change in value | N/A |

Tourism

The systematic development of the Greek tourism industry began under the Second Republic, with the establishment of the Greek National Tourism Organization (EOT) and the Tourist Police in 1929.[65] The creation of a national statistics agency also aided in the organised collection of reliable tourist information, while efforts by the government to regulate the quality of hotels saw an increase in accommodation standards.[66] The EOT also created the notion of the Greek 'summer season' by offering discounts and allowances to boat, train, and air tickets.[66] A hospitality school was founded, with staff educated in Switzerland, as well as a school for interpreters and tour guides.[66]

Data from the year 1932 indicates that 72,102 tourists visited the country, of which approximately 18,000 were Greek nationals, who were living permanently in another country.[67] The number continued to rise, and in 1935, the last year of the republic, tourist arrivals stood at 126,218.[64] Data from the same year indicated that, on average, foreign nationals stayed in Greece for 18 days, compared with 101 days for Greek nationals living permanently abroad, for a total average of 31 days stay.[68] Greeks went abroad as tourists at a much lesser frequency, with 15,562 Greeks exiting the country for tourism elsewhere, of which only a third were going abroad primarily for leisure.[68] This was due to the devaluation of the Drachma in 1932.[67]

The Statistical Yearbook of 1936 also gives information as to the type of tourism that the Second Republic was experiencing. Of all tourist arrivals in 1935, 61,855 (49%) were there mainly for leisure, 31,690 (25%) were tourists visiting Greek ports, 16,481 (13%) were tourists in transit, 7,124 (6%) were business tourists, 4,591 (4%) were visiting for family reasons, 1,180 (1%) were visiting students, and 887 (0.7%) for other purposes.[68]

Society

Demographics

| Year | Pop. | ±% |

|---|---|---|

| 1924 | 5,923,000 | — |

| 1925 | 5,992,000 | +1.2% |

| 1926 | 6,091,000 | +1.7% |

| 1927 | 6,163,000 | +1.2% |

| 1928 | 6,204,684 | +0.7% |

| 1929 | 6,303,000 | +1.6% |

| 1930 | 6,398,000 | +1.5% |

| 1931 | 6,483,000 | +1.3% |

| 1932 | 6,548,000 | +1.0% |

| 1933 | 6,630,000 | +1.3% |

| 1934 | 6,746,000 | +1.7% |

| 1935 | 6,839,000 | +1.4% |

| Source: Statistical Yearbook 1936[2] | ||

The total number of people in Greece numbered 6,204,684 people according to the census of 1928.[69] This was an increase from the census of 1920 (5,536,000 people) despite the fact that Greece lost territories with an area of approximately 20,000 square kilometres (7,700 sq mi) with a population of over half a million people in the Treaty of Lausanne.[69] Additionally, the census of the same year indicates that 1.2 million people (19% of the population of the country) registered as refugees.[69] The census revealed that there were 3.13 million women and 3.08 million men in the country.[69]

Urban life increased following the exchange of populations. In 1920 26% of people lived in urban centers and 74% in rural areas.[69] In 1928 the figures had changed to 33% and 67% respectively, primarily due to the influx of refugees.[69] Due to immigration, some cities saw tremendous growth between the censuses of 1920 and 1928, including Kavala (118%), Piraeus (85%) and Athens (54%).[69] The rapid growth in urban populations resulted in an increase in housing demand, with Athens and Piraeus showing a shortage of 39,000 houses in 1921; to combat this the government spent considerable amounts of money on social housing.[70] The country's principal urban centers in 1928 were:

Health and welfare

A major step in the creation of a welfare state in Greece was done under the Liberal government of Eleftherios Venizelos which passed Law 5733 on 11 October 1932, creating the Social Insurance Institute (Ἵδρυμα τῶν Κοινωνικῶν Ἀσφαλίσεων, IKA).[71] This unified the 50 or so social insurance programmes which were active in Greece at the time, some of which dated back to the 1830s, into a single state-operated system of universal social insurance comparable to those of industrialised nations.[72] It was heavily based on the social security system of Czechoslovakia, and the International Labour Organisation was instrumental in shaping it.[73] It would provide sick pay and workers' compensation to all those insured, but not unemployment benefits due to the complexity of unemployment welfare.[72] Its aim was to prevent a deterioration of working conditions in a climate of increased labour unionism as well as the general improvement of working conditions at a time when the state of the labouring class was characterised by the government as "appalling".[74] Additionally, labour legislation was considered to be an important preventive measure against the rise of communism.[74]

The IKA would cover all those employed in Greece (regardless of citizenship) in either the public or private sector, those employed on ships under the Greek flag, Greek citizens working abroad on behalf of companies based in Greece, those involved in the administration of labour unions, and all students.[71] Benefits would be calculated based on the insured worker's daily salary over a period of four weeks prior to the benefits being applied, from a 9-tier scale ranging from ₯0.05 to ₯200 per day.[71] Additionally, it had the power to invest its reserves in government securities or securities guaranteed by the state, profit-yielding real estate, or for loans intended for public works.[73]

Despite Law 5733 being passed, the IKA was never implemented due to objections from the various insurance programmes it would have replaced. The government of Eleftherios Venizelos fell in 1934, and the government that succeeded him failed to implement the creation of the IKA as well. The Metaxas regime which came to power after the collapse of the Second Republic capitalised greatly on the creation of the IKA in a bid to win working class support,[75] and the IKA is now considered to be one of its most long-lasting accomplishments.[76] It was launched in November 1937.[77] The Metaxas regime used the IKA's reserves to finance the regime's national plans,[73] despite this being outside the remit of the original law, but did not claim to have created the IKA; rather, this was done by those wishing to glorify the regime after its fall.[74]

Ethnic groups and migration

Like present-day Greece, the second Republic was a relatively homogenous country, with almost 94% of the population being ethnically Greek according to the census of 1928.[69] The census of 1928 showed that the percentage of Greeks in the country rose from 80.53% in the census of 1920 to 93.75% in the census of 1928.[69] In the meantime the populations of the Turkish and Bulgarian communities dropped from 13.90% and 2.51% to 1.66% and 1.32%.[69] This was because of the exchange of populations that took place in 1923 between Greece and Turkey and Bulgaria.[69] In Macedonia, the number of non-Greeks was reduced from 48% in 1920 to 12% in 1928.[78] The Great Greek Encyclopedia notes however that those minorities which remained in Macedonia "do not yet possess a Greek national consciousness".[78]

During the years of the Republic, no significant minorities existed in the country. The largest, the Turks of Western Thrace, was the only officially recognised minority in the country and numbered approximately 103,000 people or 1.66% of the population of the country.[69] Other ethnic groups with over 1.00% of the population were the Bulgars (1.33%) and the Jews of Salonica (1.13%).[69] Foreign citizens accounted for an additional 1.18% of the population, while Armenians and Albanians for 0.56% and 0.40% respectively.[69]

Migration was a big issue in Greece in the late 19th and early 20th century, with 485,936 people leaving the country for the New World between 1821 and 1932.[67] During the Second Republic yearly transatlantic migration numbers dropped considerably, from 8,152 in 1924 to 2,821 in 1932.[67] Overall migration figures for 1931 show net migration to the country, with 17,384 people relocating to Greece and 15,060 migrating abroad; in 1932 there net migration from the country, with 17,245 arrivals and 19,712 departures.[67] Migration figures from that year show that the lion's share of migrants departed for the Transcaucasian Socialist Federative Soviet Republic (5,407), followed by Egypt (2,825), Romania (2,352), and the United States (2,281).[67]

Languages

The homogeneity of the Second Republic in terms of ethnic composition was also reflected in its languages. In the 1928 Census, 92.8% of the population listed Greek as their primary language, followed by Turkish (3.1%), and Macedonian (1.3%, listed in the Census as Macedonoslavic).[79] The degree to which the Census of 1928 reflected the actual linguistic situation in Greece is debated, as internal government documents from 1932 put the number of Slavic speakers in the Florina prefecture alone at 80,000 (61%), as opposed to 81,984 for the entire country in the Census.[80][79]

Additionally, there were two official varieties of the Greek language vying for supremacy in the Greek language question; the official language of the state, or Katharevousa, was a constructed language based on Attic Greek, while Demotic was the popular language and had evolved naturally from Medieval Greek. The decision to teach one or the other in schools was always controversial, and during the Second Republic the language of instruction changed numerous times: Demotic in 1923, Katharevousa in 1924, both in 1927, Demotic in 1931, and Katharevousa in 1933.[81] After the fall of the Second Republic, the 4th of August Regime of Ioannis Metaxas brought back Demotic in 1939, only to be replaced by Katharevousa again during the Axis occupation of Greece in 1941.[81] Standard Modern Greek finally won the debate only in 1976, becoming the sole official language and overcoming the hurdle to intellectual and scientific advancement that the state of diglossia had imposed upon the country since its creation.[81]

Beginning in 1925 the government introduced an alphabet book, called the Abecedar, for the country's Slavic-speaking minority as part of its obligations towards Bulgaria from the Treaty of Sèvres. The book was based on the dialect of Florina (Lerin in the Slavic tongues), and used the Latin rather than the Cyrillic alphabet.[80] The Ministry of Education described it as a textbook for "the children of Slav speakers in Greece [...] printed in the Latin script and compiled in the Macedonian dialect".[80] This proved controversial not only in Greece, but also in Serbia and Bulgaria.[80] The Abecedar was eventually withdrawn, and never reached classrooms.

Education

Literacy of persons aged 8+ in Greece stood at 59% in 1928, with a sharp contrast between men (77%) and women (42%).[82] Literacy rates also varied widely between regions, ranging from 66% for Central Greece & Euboea and 63% for the Aegean islands, to 50% for Epirus and 39% for Thrace.[82]

To remedy this, the government of Eleftherios Venizelos began an ambitious school-building program spanning 1928 to 1932. Twice as many schools were built in four years than had been built between 1828 and 1928; 3,167 schools with 8,200 classrooms were constructed at a cost of ₯1.5 billion.[83] The investment was financed in part by a £1 million loan from a Swedish bank (£61 million in today's value), and through the country's budget surplus.[83] A welcome side effect of the building program were the more hygienic conditions in schools, which contributed to the decline of ill students as a percentage of the total student population from 24.5% in 1926/1927 to 18.2% in 1931/1932.[83] The number of students in public primary education, meanwhile, grew from 655,839 in 1928 to 864,401 in 1934.[84]

By the end of the Republic, Greece's public educational infrastructure included 545 nurseries, 7,764 primary schools, 399 secondary schools, and 7 institutions of higher education (including 3 universities: Aristotle University of Thessaloniki, the National and Kapodistrian University of Athens, and the National Technical University of Athens).[85]

Bibliography

Sources

- Ioannis D. Stefanidis (2006), "Reconstructing Greece as a European State: Venizelos' Last Premiership 1928–1932", Eleftherios Venizelos - The Trials of Statesmanship, Edinburgh University Press, ISBN 978-074-863-364-7

- Karolidis, Pavlos (1930), Moschopoulos, Th.Th. (ed.), translated by Moschopoulos, P., "Από τον Α' Παγκόσμιο Πόλεμο μέχρι το 1930" [From World War 1 to 1930], Ιστορία του Ελληνικού Έθνους στη Σημερινή Γλώσσα (in Greek) (1993 ed.), Athens: Cactus Editions, 20, pp. 266–353, ISBN 978-960-382-818-1

- Mavrogordatos, George Themistocles (1983), Stillborn Republic: Social Coalitions and Party Strategies in Greece, 1922–1936, Berkeley: University of California Press, ISBN 978-0-520-04358-9

- "Ἑλλάς - Ἑλληνισμὸς" [Greece - Hellenism], Μεγάλη Ἐλληνικὴ Ἐγκυκλοπαιδεῖα, Athens: Pyrsos Co. Ltd., 10, 1934

- Tzokas, Spyros (2002), Ο Ελευθέριος Βενιζέλος και το Εγχείρημα του Αστικού Εκσυχρονισμού 1928–1932 [Eleftherios Venizelos and the Attempt at Urban Modernisation 1928–1932], Athens: Themelio, ISBN 978-960-310-286-1

Primary sources

The following are publicly available primary sources relating to the era of the Second Hellenic Republic, in the Greek language, primarily in the form of statistical yearbooks. These aimed to "provide a picture of life in Greece through numbers".[86]

- Michalopoulos, Ioannis G., ed. (May 1931), Στατιστικὴ Ἑπετηρὶς τῆς Ἑλλάδος–1930 [Statistical Yearbook of Greece–1930] (PDF) (in Greek and French), Athens: Hellenic Statistical Authority, archived from the original (PDF) on 3 March 2016

- ——, ed. (April 1932), Στατιστικὴ Ἑπετηρὶς τῆς Ἑλλάδος–1931 [Statistical Yearbook of Greece–1931] (PDF) (in Greek and French), Athens: Hellenic Statistical Authority, archived from the original (PDF) on 31 August 2018

- ——, ed. (April 1934), Στατιστικὴ Ἑπετηρὶς τῆς Ἑλλάδος–1933 [Statistical Yearbook of Greece–1933] (PDF) (in Greek and French), Athens: Hellenic Statistical Authority, archived from the original (PDF) on 31 August 2018

- ——, ed. (June 1935), Στατιστικὴ Ἑπετηρὶς τῆς Ἑλλάδος–1934 [Statistical Yearbook of Greece–1934] (PDF) (in Greek and French), Athens: Hellenic Statistical Authority, archived from the original (PDF) on 31 January 2019

- ——, ed. (June 1936), Στατιστικὴ Ἑπετηρὶς τῆς Ἑλλάδος–1935 [Statistical Yearbook of Greece–1935] (PDF) (in Greek and French), Athens: Hellenic Statistical Authority, archived from the original (PDF) on 31 August 2018

- ——, ed. (May 1937), Στατιστικὴ Ἑπετηρὶς τῆς Ἑλλάδος–1936 [Statistical Yearbook of Greece–1936] (PDF) (in Greek and French), Athens: Hellenic Statistical Authority, archived from the original (PDF) on 31 August 2018 – This yearbook concerns the first year after the restoration of the monarchy.

- Σύνταγμα τῆς Ἑλληνικὴς Δημοκρατίας [Constitution of the Hellenic Republic] (PDF) (in Greek), Athens: Hellenic Parliament, 3 June 1927, archived from the original (PDF) on 3 October 2018

References

- "Newspaper of the Government - Issue 64". Government Newspaper of the Hellenic State. 25 March 1924. Retrieved 18 August 2012.

- Statistical Yearbook of Greece–1936, p. 416.

- "Newspaper of the Government - Issue 456". Government Newspaper of the Kingdom of Greece. 10 October 1935. Retrieved 18 August 2012.

- "Newspaper of the Government - Issue 120". Government Newspaper of the Hellenic Republic. 28 May 1924. Retrieved 18 August 2012.

- "Δημοκρατία". Word Reference. Retrieved 2019-10-19.

- Karolidis, Pavlos (1993). Ιστορία του Ελληνικού Έθνους [History of the Greek Nation]. 20. Cactus Publishing Enterprises. p. 276.

- Karolidis, Pavlos (1993). Ιστορία του Ελληνικού Έθνους [History of the Greek Nation]. 20. Cactus Publishing Enterprises. p. 289.

- 100+1 Χρόνια Ελλάδα [100+1 Years of Greece]. A. I Maniateas Publishing Enterprises. 1999. pp. 182–183.

- "Newspaper of the Government - Issue 70". Government Newspaper of the Hellenic State. 29 March 1924. Retrieved 2 March 2014.

- "Empros". National Library of Greece. 14 April 1924. Retrieved 4 March 2014.

- "Skrip". National Library of Greece. 14 April 1924. Retrieved 4 March 2014.

- "Rizospastis". National Library of Greece. 14 April 1924. Retrieved 4 March 2014.

- "Makedonia". National Library of Greece. 14 April 1924. Retrieved 4 March 2014.

- "Newspaper of the Government - Issue 93". Government Newspaper of the Kingdom of Greece. 23 April 1924. Retrieved 4 March 2014.

- 100+1 Χρόνια Ελλάδα [100+1 Years of Greece]. A. I Maniateas Publishing Enterprises. 1999. p. 189.

- "Inflation calculator". Bank of England.

- United Nations for the Classroom. p. 15.

- Fellows, Nick (September 2012). History for the IB Diploma: Peacemaking, Peacekeeping: International Relations 1918-36. Cambridge University Press. p. 132. ISBN 978-1107613911.

- Seferiadis, Seraphim (January 2005). "The Coercive Impulse: Policing Labour in Interwar Greece". Journal of Contemporary History. 40 (1): 55–78. doi:10.1177/0022009405049266. JSTOR 30036309.

- Constitution of the Hellenic Republic, Chapter One: Form and Basis of the Government.

- Constitution of the Hellenic Republic, Chapter Two: Public Law of the Greeks.

- Constitution of the Hellenic Republic, Chapter Fourteen: Enforcement and Amendment of the Constitution.

- Constitution of the Hellenic Republic, Chapter Four: Legislative Power.

- "Register of Senators and Deputies" (PDF). National Printing House, Hellenic Parliament. 1977. Retrieved 28 February 2013.

- Great Greek Encyclopedia, p. 861.

- Great Greek Encyclopedia, p. 871.

- "Register of Senators and Deputies" (PDF). National Printing House, Hellenic Parliament. 1977. Retrieved 28 February 2013.

- Emm. Papadakis, Nikolaos (2006). Eleftherios K. Venizelos - A Biography. National Research Foundation "Eleftherios K. Venizelos". pp. 48–50.

- 100+2 Χρόνια Ελλάδα [100+2 Years of Greece]. A. I Maniateas Publishing Enterprises. 2002. pp. 208–209.

- 100+2 Χρόνια Ελλάδα [100+2 Years of Greece]. A. I Maniateas Publishing Enterprises. 2002. pp. 230–231.

- Statistical Yearbook of Greece–1931, p. 23–24.

- Evans, Idrisyn Oliver (1959). The Observer's Book of Flags (1975 ed.). F. Warne. p. 128. ISBN 9780723215288.

- Hatzilyras, Alexandros Michail (March 2003). "Η καθιέρωση της ελληνικής σημαίας" [The adoption of the Greek flag]. Hellenic Army General Staff (in Greek). Archived from the original on 2 April 2007. Retrieved 23 October 2019.

- Great Greek Encyclopedia, p. 243.

- Great Greek Encyclopedia, p. 281.

- Great Greek Encyclopedia, p. 296.

- Great Greek Encyclopedia, p. 299–300.

- Statistical Yearbook of Greece–1936, p. 344.

- "Yearly Statistics of Greece" (PDF). National Printing House. 1934. Retrieved 27 February 2013.

- Maddison Project (2018). "Maddison Project Database 2018". Retrieved 29 January 2019.

- Great Greek Encyclopedia, p. 338.

- Great Greek Encyclopedia, p. 339.

- Statistical Yearbook of Greece–1936, p. 482.

- "Yearly Statistics of Greece" (PDF). National Printing House. 1935. Retrieved 27 February 2013.

- "Yearly Statistics of Greece" (PDF). National Printing House. 1930. Retrieved 27 February 2013.

- Statistical Yearbook of Greece–1936, p. 338.

- "Yearly Statistics of Greece" (PDF). National Printing House. 1931. Retrieved 27 February 2013.

- Statistical Yearbook of Greece–1936, p. 172.

- Great Greek Encyclopedia, p. 150.

- Ioannis D. Stefanidis (2006). "6". Reconstructing Greece as a European State: Venizelos' Last Premiership 1928–1932. Eleftherios Venizelos - The Trials of Statesmanship. Edinburgh University Press. ISBN 074-863-364-2. Retrieved 25 August 2012.

- Great Greek Encyclopedia, p. 153–154.

- Great Greek Encyclopedia, p. 162.

- Statistical Yearbook of Greece–1936, p. 168.

- "Οικονομικό Δελτίο" [Financial Report] (PDF). www.bankofgreece.gr. Bank of Greece. July 1999.

- Tzokas, Spyros (2002). Το αναπτυξιακό έργο της κυβέρνησης Βενιζέλου [The investment programme of the Venizelos government]. Ο Ελευθέριος Βενιζέλος και το Εγχείρημα του Αστικού Εκσυχρονισμού 1928–1932 [Eleftherios Venizelos and the Attempt at Urban Modernisation 1928–1932]. Athens: Themelio. p. 130. ISBN 978-960-310-286-1.

- Great Greek Encyclopedia, p. 155.

- Statistical Yearbook of Greece–1931, p. 125.

- Christine Agriantoni (2006). "10". Venizelos and Economic Policy. Eleftherios Venizelos - The Trials of Statesmanship. Edinburgh University Press. Retrieved 25 August 2012.

- Sophia Lazaretou (2003). "Greek Monetary Economics in Retrospect: The Adventures of the Drachma" (PDF). National Bank of Greece. Retrieved 2 March 2014.

- Michalis M. Psalidopoulos (2011). "Monetary Management and Economic Crisis: The Policy of the Bank of Greece, 1929–1941" (PDF). National Bank of Greece. Retrieved 2 March 2014.

- Statistical Yearbook of Greece–1936, p. 524.

- "Δραχμή" [Drachma]. www.bankofgreece.gr. Bank of Greece. Retrieved 30 January 2019.

- Statistical Yearbook of Greece–1936, p. 525.

- Statistical Yearbook of Greece–1936, p. 106.

- Greek National Tourism Organization. "Ιστορία" [History]. www.gnto.gov.gr (in Greek). Retrieved 2 September 2018.

- Tzokas, Spyros (2002). Το αναπτυξιακό έργο της κυβέρνησης Βενιζέλου [The investment programme of the Venizelos government]. Ο Ελευθέριος Βενιζέλος και το Εγχείρημα του Αστικού Εκσυχρονισμού 1928–1932 [Eleftherios Venizelos and the Attempt at Urban Modernisation 1928–1932]. Athens: Themelio. pp. 146–149. ISBN 978-960-310-286-1.

- Great Greek Encyclopedia, p. 223–237.

- Statistical Yearbook of Greece–1936, p. 111–113.

- A. A. Pallis (1929). "The Greek Census of 1928". The Geographical Journal. 73 (6): 543–548. doi:10.2307/1785338. JSTOR 1785338.

- Great Greek Encyclopedia, p. 412.

- Νόμος 5733 [Law 5733] (PDF) (in Greek), Athens: Hellenic Parliament, 11 October 1932

- Great Greek Encyclopedia, p. 414.

- Rapti, Vasiliki (2007). Gro, Hagemann (ed.). Reciprocity and Redistribution: Work and Welfare Reconsidered. Edizioni Plus – Pisa University Press. p. 48. ISBN 9788884924650.

- Teneketzis, K. (2007). "Κοινωνικες συνθήκες υπό το καθεστώς της 4ης Αυγούστου 1936" (PDF). Journal of the Technical Education Institute of Piraeus (in Greek). XI: 29–52. ISSN 1106-4110.

- Gunther, Richard; Diamandouros, Nikiforos P. (2006-11-16). Democracy And the State in the New Southern Europe. Oxford University Press. p. 121. ISBN 9780199202812.

- Vatikiotis, P. J. (1998). Popular Autocracy in Greece, 1936-1941: A Political Biography of General Ioannis Metaxas. Routledge. ISBN 9781134729333.

- Petrakis, Marina (2006). Metaxas Myth: Dictatorship and Propaganda in Greece. Tauris Academic Studies. p. 59. ISBN 9780857714701.

- Great Greek Encyclopedia, p. 408.

- Statistical Yearbook of Greece–1936, p. 71.

- Danforth, Loring M. (1997-04-06). The Macedonian Conflict: Ethnic Nationalism in a Transnational World. Princeton University Press. pp. 69–72. ISBN 978-069-104-356-2.

- Babiniotis, Georgios (2002). Συνοπτική Ιστορία Της Ελληνικής Γλώσσας [A Concise History of the Greek Language] (Fifth ed.). pp. 199–202.

- Statistical Yearbook of Greece–1936, p. 55–56.

- Tzokas, Spyros (2002). Τα δημόσια και παραγωγικά έργα της τετραετίας [The public and productive works of the four-year government]. Ο Ελευθέριος Βενιζέλος και το Εγχείρημα του Αστικού Εκσυχρονισμού 1928–1932 [Eleftherios Venizelos and the Attempt at Urban Modernisation 1928–1932]. Athens: Themelio. pp. 159–161. ISBN 978-960-310-286-1.

- Statistical Yearbook of Greece–1936, p. 353–354.

- Statistical Yearbook of Greece–1936, p. 352.

- Statistical Yearbook of Greece–1933, Preamble.

External links

- Hellenic Parliament - Constitutional History of Greece

- Greece during the Interwar Period, 1923–1940, from the Foundation of the Hellenic World

.svg.png)

.svg.png)

.svg.png)

.svg.png)

.jpg)