Lombards

The Lombards (/ˈlɒmbərdz, -bɑːrdz, ˈlʌm-/)[1] or Langobards (Latin: Langobardi) were a Germanic people who ruled most of the Italian Peninsula from 568 to 774.

The medieval Lombard historian Paul the Deacon wrote in the History of the Lombards (written between 787 and 796) that the Lombards descended from a small tribe called the Winnili,[2] who dwelt in southern Scandinavia[3] (Scadanan) before migrating to seek new lands. Roman-era authors however reported them in the 1st century AD, as one of the Suebian peoples, in what is now northern Germany, near the Elbe river. By the end of the 5th century, the Lombards had moved into the area roughly coinciding with modern Austria and Slovakia north of the Danube river, where they subdued the Heruls and later fought frequent wars with the Gepids. The Lombard king Audoin defeated the Gepid leader Thurisind in 551 or 552; his successor Alboin eventually destroyed the Gepids in 567.

Following this victory, Alboin decided to lead his people to Italy, which had become severely depopulated and devastated after the long Gothic War (535–554) between the Byzantine Empire and the Ostrogothic Kingdom there. In contrast with the Goths and the Vandals, the Lombards left Scandinavia and descended south through Germany, Austria and Slovenia, only leaving Germanic territory a few decades before reaching Italy. The Lombards would have consequently remained a predominantly Germanic tribe by the time they invaded Italy.[4] The Lombards were joined by numerous Saxons, Heruls, Gepids, Bulgars, Thuringians, and Ostrogoths, and their invasion of Italy was almost unopposed. By late 569 they had conquered all of northern Italy and the principal cities north of the Po River except Pavia, which fell in 572. At the same time, they occupied areas in central Italy and southern Italy. They established a Lombard Kingdom in north and central Italy, later named Regnum Italicum ("Kingdom of Italy"), which reached its zenith under the 8th-century ruler Liutprand. In 774, the Kingdom was conquered by the Frankish King Charlemagne and integrated into his Empire. However, Lombard nobles continued to rule southern parts of the Italian peninsula well into the 11th century, when they were conquered by the Normans and added to their County of Sicily. In this period, the southern part of Italy still under Longobardic domination was known to the foreigners by the name Langbarðaland (Land of the Lombards), in the Norse runestones.[5] Their legacy is also apparent in the regional name Lombardy (in the north of Italy).

Name

According to their own traditions, the Lombards initially called themselves the Winnili. After a reported major victory against the Vandals in the 1st century, they changed their name to Lombards.[6] The name Winnili is generally interpret as 'the wolves', related to the Proto-Germanic root *wulfaz 'wolf'.[7] The name Lombard was reportedly derived from the distinctively long beards of the Lombards.[8] It is probably a compound of the Proto-Germanic elements *langaz (long) and *bardaz (beard).

History

Early history

Legendary origins

According to their own legends the Lombards originated in southern Scandinavia.[14] The Northern European origins of the Lombards is supported by genetic,[15][16] anthropological,[14] archaeological and earlier literary evidence.[14]

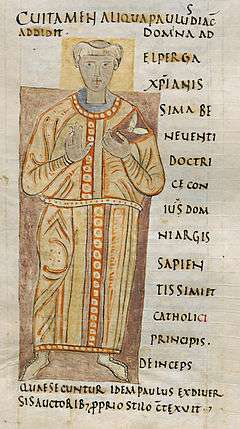

A legendary account of Lombard origins, history, and practices is the Historia Langobardorum (History of the Lombards) of Paul the Deacon, written in the 8th century. Paul's chief source for Lombard origins, however, is the 7th-century Origo Gentis Langobardorum (Origin of the Lombard People).

The Origo Gentis Langobardorum tells the story of a small tribe called the Winnili[2] dwelling in southern Scandinavia[3] (Scadanan) (the Codex Gothanus writes that the Winnili first dwelt near a river called Vindilicus on the extreme boundary of Gaul).[17] The Winnili were split into three groups and one part left their native land to seek foreign fields. The reason for the exodus was probably overpopulation.[18] The departing people were led by the brothers Ybor and Aio and their mother Gambara[19][20] and arrived in the lands of Scoringa, perhaps the Baltic coast[21] or the Bardengau on the banks of the Elbe.[22] Scoringa was ruled by the Vandals and their chieftains, the brothers Ambri and Assi, who granted the Winnili a choice between tribute or war.

The Winnili were young and brave and refused to pay tribute, saying "It is better to maintain liberty by arms than to stain it by the payment of tribute."[23] The Vandals prepared for war and consulted Godan (the god Odin[3]), who answered that he would give the victory to those whom he would see first at sunrise.[24] The Winnili were fewer in number[23] and Gambara sought help from Frea (the goddess Frigg[3]), who advised that all Winnili women should tie their hair in front of their faces like beards and march in line with their husbands. At sunrise, Frea turned her husband's bed so that he was facing east, and woke him. So Godan spotted the Winnili first and asked, "Who are these long-beards?," and Frea replied, "My lord, thou hast given them the name, now give them also the victory."[25] From that moment onwards, the Winnili were known as the Longbeards (Latinised as Langobardi, Italianised as Longobardi, and Anglicized as Langobards or Lombards).

When Paul the Deacon wrote the Historia between 787 and 796 he was a Catholic monk and devoted Christian. He thought the pagan stories of his people "silly" and "laughable".[24][26] Paul explained that the name "Langobard" came from the length of their beards.[27] A modern theory suggests that the name "Langobard" comes from Langbarðr, a name of Odin.[28] Priester states that when the Winnili changed their name to "Lombards", they also changed their old agricultural fertility cult to a cult of Odin, thus creating a conscious tribal tradition.[29] Fröhlich inverts the order of events in Priester and states that with the Odin cult, the Lombards grew their beards in resemblance of the Odin of tradition and their new name reflected this.[30] Bruckner remarks that the name of the Lombards stands in close relation to the worship of Odin, whose many names include "the Long-bearded" or "the Grey-bearded", and that the Lombard given name Ansegranus ("he with the beard of the gods") shows that the Lombards had this idea of their chief deity.[31] The same Old Norse root Barth or Barði, meaning "beard", is shared with the Heaðobards mentioned in both Beowulf and in Widsith, where they are in conflict with the Danes. They were possibly a branch of the Langobards.[32][33]

Alternatively some etymological sources suggest an Old High German root, barta, meaning “axe” (and related to English halberd), while Edward Gibbon puts forth an alternative suggestion which argues that:

…Börde (or Börd) still signifies “a fertile plain by the side of a river,” and a district near Magdeburg is still called the lange Börde. According to this view Langobardi would signify “inhabitants of the long bord of the river;” and traces of their name are supposed still to occur in such names as Bardengau and Bardewick in the neighborhood of the Elbe.[34]

According to the Gallaecian Christian priest, historian and theologian Paulus Orosius (translated by Daines Barrington), the Lombards or Winnili lived originally in the Vinuiloth (Vinovilith) mentioned by Jordanes, in his masterpiece Getica, to the north of Uppsala, Sweden. Scoringa was near the province of Uppland, so just north of Östergötland.

The footnote then explains the etymology of the name Scoringa:

The shores of Uppland and Östergötland are covered with small rocks and rocky islands, which are called in German Schæren and in Swedish Skiaeren. Heal signifies a port in the northern languages; consequently Skiæren-Heal is the port of the Skiæren, a name well adapted to the port of Stockholm, in the Upplandske Skiæren, and the country may be justly called Scorung or Skiærunga.[35]

The legendary king Sceafa of Scandza was an ancient Lombardic king in Anglo-Saxon legend. The Old English poem Widsith, in a listing of famous kings and their countries, has Sceafa [weold] Longbeardum, so naming Sceafa as ruler of the Lombards.[36]

Similarities between Langobardic and Gothic migration traditions have been noted among scholars. These early migration legends suggest that a major shifting of tribes occurred sometime between the 1st and 2nd century BC, which would coincide with the time that the Teutoni and Cimbri left their homelands in Scandinavia and migrated through Germany, eventually invading Roman Italy.

Archaeology and migrations

.png)

The first mention of the Lombards occurred between AD 9 and 16, by the Roman court historian Velleius Paterculus, who accompanied a Roman expedition as prefect of the cavalry.[37] Paterculus says that under Tiberius the "power of the Langobardi was broken, a race surpassing even the Germans in savagery".[38]

From the combined testimony of Strabo (AD 20) and Tacitus (AD 117), the Lombards dwelt near the mouth of the Elbe shortly after the beginning of the Christian era, next to the Chauci.[37] Strabo states that the Lombards dwelt on both sides of the Elbe.[37] He treats them as a branch of the Suebi, and states that:

Now as for the tribe of the Suebi, it is the largest, for it extends from the Rhenus to the Albis; and a part of them even dwells on the far side of the Albis, as, for instance, the Hermondori and the Langobardi; and at the present time these latter, at least, have, to the last man, been driven in flight out of their country into the land on the far side of the river.[39]

Suetonius wrote that Roman general Nero Drusus defeated a large force of Germans and drove some “to the farther side of the Albis (Elbe)” river. It is conceivable that these refugees were the Langobardi and the Hermunduri mentioned by Strabo not long after.[40]

The German archaeologist Willi Wegewitz defined several Iron Age burial sites at the Lower Elbe as Langobardic.[41] The burial sites are crematorial and are usually dated from the 6th century BC through the 3rd century AD, so a settlement breakoff seems unlikely.[42] The lands of the lower Elbe fall into the zone of the Jastorf Culture and became Elbe-Germanic, differing from the lands between Rhine, Weser, and the North Sea.[43] Archaeological finds show that the Lombards were an agricultural people.[44]

Tacitus also counted the Lombards as a remote and aggressive Suebian tribe, one of those united in worship of the deity Nerthus, who he referred to as "Mother Earth", and also as subjects of Marobod the King of the Marcomanni.[45] Marobod had made peace with the Romans, and that is why the Lombards were not part of the Germanic confederacy under Arminius at the Battle of Teutoburg Forest in AD 9. In AD 17, war broke out between Arminius and Marobod. Tacitus records:

Not only the Cheruscans and their confederates... took arms, but the Semnones and Langobards, both Suebian nations, revolted to him from the sovereignty of Marobod... The armies... were stimulated by reasons of their own, the Cheruscans and the Langobards fought for their ancient honor or their newly acquired independence. . . .[45]

In 47, a struggle ensued amongst the Cherusci and they expelled their new leader, the nephew of Arminius, from their country. The Lombards appeared on the scene with sufficient power to control the destiny of the tribe that had been the leader in the struggle for independence thirty-eight years earlier, for they restored the deposed leader to sovereignty.[46]

To the south, Cassius Dio reported that just before the Marcomannic Wars, 6,000 Lombards and Obii (sometimes thought to be Ubii), crossed the Danube and invaded Pannonia.[47] The two tribes were defeated, whereupon they ceased their invasion and sent Ballomar, King of the Marcomanni, as ambassador to Aelius Bassus, who was then administering Pannonia. Peace was made and the two tribes returned to their homes, which in the case of the Lombards was the lands of the lower Elbe.[48] At about this time, in his Germania Tacitus says that "their scanty numbers are a distinction" because "surrounded by a host of most powerful tribes, they are safe, not by submitting, but by daring the perils of war".[49]

In the mid-2nd century, the Lombards supposedly appeared in the Rhineland, because according to Claudius Ptolemy, the Suebic Lombards lived "below" the Bructeri and Sugambri, and between these and the Tencteri. To their east stretching northwards to the central Elbe are the Suebi Angili.[50] But Ptolemy also mentions the "Laccobardi" to the north of the above-mentioned Suebic territories, east of the Angrivarii on the Weser, and south of the Chauci on the coast, probably indicating a Lombard expansion from the Elbe to the Rhine.[51] This double mention has been interpreted as an editorial error by Gudmund Schütte, in his analysis of Ptolemy.[52] However, the Codex Gothanus also mentions Patespruna (Paderborn) in connection with the Lombards.[53]

From the 2nd century onwards, many of the Germanic tribes recorded as active during the Principate started to unite into bigger tribal unions, such as the Franks, Alamanni, Bavarii, and Saxons.[54] The Lombards are not mentioned at first, perhaps because they were not initially on the border of Rome, or perhaps because they were subjected to a larger tribal union, like the Saxons.[54] It is, however, highly probable that, when the bulk of the Lombards migrated, a considerable part remained behind and afterwards became absorbed by the Saxon tribes in the Elbe region, while the emigrants alone retained the name of Lombards.[55] However, the Codex Gothanus states that the Lombards were subjected by the Saxons around 300 but rose up against them under their first king, Agelmund, who ruled for 30 years.[56] In the second half of the 4th century, the Lombards left their homes, probably due to bad harvests, and embarked on their migration.[57]

The migration route of the Lombards in 489, from their homeland to "Rugiland", encompassed several places: Scoringa (believed to be their land on the Elbe shores), Mauringa, Golanda, Anthaib, Banthaib, and Vurgundaib (Burgundaib).[58] According to the Ravenna Cosmography, Mauringa was the land east of the Elbe.[59]

The crossing into Mauringa was very difficult. The Assipitti (possibly the Usipetes) denied them passage through their lands and a fight was arranged for the strongest man of each tribe. The Lombard was victorious, passage was granted, and the Lombards reached Mauringa.[60]

The Lombards departed from Mauringa and reached Golanda. Scholar Ludwig Schmidt thinks this was further east, perhaps on the right bank of the Oder.[61] Schmidt considers the name the equivalent of Gotland, meaning simply "good land."[62] This theory is highly plausible; Paul the Deacon mentions the Lombards crossing a river, and they could have reached Rugiland from the Upper Oder area via the Moravian Gate.[63]

Moving out of Golanda, the Lombards passed through Anthaib and Banthaib until they reached Vurgundaib, believed to be the old lands of the Burgundes.[64][65] In Vurgundaib, the Lombards were stormed in camp by "Bulgars" (probably Huns)[66] and were defeated; King Agelmund was killed and Laimicho was made king. He was in his youth and desired to avenge the slaughter of Agelmund.[67] The Lombards themselves were probably made subjects of the Huns after the defeat but rose up and defeated them with great slaughter,[68] gaining great booty and confidence as they "became bolder in undertaking the toils of war."[69]

In the 540s, Audoin (ruled 546–560) led the Lombards across the Danube once more into Pannonia, where they received Imperial subsidies as Justinian encouraged them to battle the Gepids. In 552, the Byzantines, aided by a large contingent of Foederati, notably Lombards, Heruls and Bulgars, defeated the last Ostrogoths led by Teia in the Battle of Taginae.[70]

Kingdom in Italy, 568–774

Invasion and conquest of the Italian peninsula

In approximately 560, Audoin was succeeded by his son Alboin, a young and energetic leader who defeated the neighboring Gepidae and made them his subjects; in 566, he married Rosamund, daughter of the Gepid king Cunimund. In the spring of 568, Alboin led the Lombard migration into Italy.[71] According to the History of the Lombards, "Then the Langobards, having left Pannonia, hastened to take possession of Italy with their wives and children and all their goods."[72]

Various other peoples who either voluntarily joined or were subjects of King Alboin were also part of the migration.[71] "Whence, even until today, we call the villages in which they dwell Gepidan, Bulgarian, Sarmatian, Pannonian, Suabian, Norican, or by other names of this kind."[73] At least 20,000 Saxon warriors, old allies of the Lombards, and their families joined them in their new migration.[74]

The first important city to fall was Forum Iulii (Cividale del Friuli) in northeastern Italy, in 569. There, Alboin created the first Lombard duchy, which he entrusted to his nephew Gisulf. Soon Vicenza, Verona and Brescia fell into Germanic hands. In the summer of 569, the Lombards conquered the main Roman centre of northern Italy, Milan. The area was then recovering from the terrible Gothic Wars, and the small Byzantine army left for its defence could do almost nothing. Longinus, the Exarch sent to Italy by Emperor Justin II, could only defend coastal cities that could be supplied by the powerful Byzantine fleet. Pavia fell after a siege of three years, in 572, becoming the first capital city of the new Lombard kingdom of Italy.

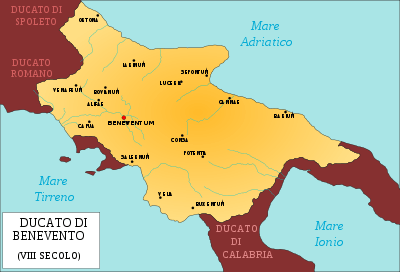

In the following years, the Lombards penetrated further south, conquering Tuscany and establishing two duchies, Spoleto and Benevento under Zotto, which soon became semi-independent and even outlasted the northern kingdom, surviving well into the 12th century. Wherever they went, they were joined by the Ostrogothic population, which was allowed to live peacefully in Italy with their Rugian allies under Roman sovereignty.[75] The Byzantines managed to retain control of the area of Ravenna and Rome, linked by a thin corridor running through Perugia.

When they entered Italy, some Lombards retained their native form of paganism, while some were Arian Christians. Hence they did not enjoy good relations with the Early Christian Church. Gradually, they adopted Roman or Romanized titles, names, and traditions, and partially converted to orthodoxy (in the 7th century), though not without a long series of religious and ethnic conflicts. By the time Paul the Deacon was writing, the Lombard language, dress and even hairstyles had nearly all disappeared in toto.[76]

The whole Lombard territory was divided into 36 duchies, whose leaders settled in the main cities. The king ruled over them and administered the land through emissaries called gastaldi. This subdivision, however, together with the independent indocility of the duchies, deprived the kingdom of unity, making it weak even when compared to the Byzantines, especially since these had begun to recover from the initial invasion. This weakness became even more evident when the Lombards had to face the increasing power of the Franks. In response, the kings tried to centralize power over time, but they definitively lost control over Spoleto and Benevento in the attempt.

Langobardia major

- Duchy of Friuli

- Duchy of Trent

- Duchy of Persiceta

- Duchy of Pavia

- Duchy of Tuscia

Langobardia minor

- Duchy of Spoleto and List of Dukes of Spoleto

- Duchy of Benevento and List of Dukes and Princes of Benevento

Arian monarchy

In 572, Alboin was murdered in Verona in a plot led by his wife, Rosamund, who later fled to Ravenna. His successor, Cleph, was also assassinated, after a ruthless reign of 18 months. His death began an interregnum of years (the "Rule of the Dukes") during which the dukes did not elect any king, a period regarded as a time of violence and disorder. In 586, threatened by a Frankish invasion, the dukes elected Cleph's son, Authari, as king. In 589, he married Theodelinda, daughter of Garibald I of Bavaria, the Duke of Bavaria. The Catholic Theodelinda was a friend of Pope Gregory I and pushed for Christianization. In the meantime, Authari embarked on a policy of internal reconciliation and tried to reorganize royal administration. The dukes yielded half their estates for the maintenance of the king and his court in Pavia. On the foreign affairs side, Authari managed to thwart the dangerous alliance between the Byzantines and the Franks.

Authari died in 591 and was succeeded by Agilulf, the duke of Turin, who also married Theodelinda in the same year. Agilulf successfully fought the rebel dukes of northern Italy, conquering Padua in 601, Cremona and Mantua in 603, and forcing the Exarch of Ravenna to pay tribute. Agilulf died in 616; Theodelinda reigned alone until 628 when she was succeeded by Adaloald. Arioald, the head of the Arian opposition who had married Theodelinda's daughter Gundeperga, later deposed Adaloald.

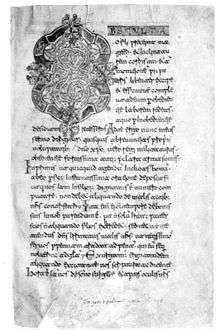

Arioald was succeeded by Rothari, regarded by many authorities as the most energetic of all Lombard kings. He extended his dominions, conquering Liguria in 643 and the remaining part of the Byzantine territories of inner Veneto, including the Roman city of Opitergium (Oderzo). Rothari also made the famous edict bearing his name, the Edictum Rothari, which established the laws and the customs of his people in Latin: the edict did not apply to the tributaries of the Lombards, who could retain their own laws. Rothari's son Rodoald succeeded him in 652, still very young, and was killed by his opponents.

At the death of King Aripert I in 661, the kingdom was split between his children Perctarit, who set his capital in Milan, and Godepert, who reigned from Pavia (Ticinum). Perctarit was overthrown by Grimoald, son of Gisulf, duke of Friuli and Benevento since 647. Perctarit fled to the Avars and then to the Franks. Grimoald managed to regain control over the duchies and deflected the late attempt of the Byzantine emperor Constans II to conquer southern Italy. He also defeated the Franks. At Grimoald's death in 671 Perctarit returned and promoted tolerance between Arians and Catholics, but he could not defeat the Arian party, led by Arachi, duke of Trento, who submitted only to his son, the philo-Catholic Cunincpert.

The Lombards engaged in fierce battles with Slavic peoples during these years: from 623–26 the Lombards unsuccessfully attacked the Carantanians, and, in 663–64, the Slavs raided the Vipava Valley and the Friuli.

Catholic monarchy

Religious strife and the Slavic raids remained a source of struggle in the following years. In 705, the Friuli Lombards were defeated and lost the land to the west of the Soča River, namely the Gorizia Hills and the Venetian Slovenia.[78] A new ethnic border was established that has lasted for over 1200 years up until the present time.[78][79]

The Lombard reign began to recover only with Liutprand the Lombard (king from 712), son of Ansprand and successor of the brutal Aripert II. He managed to regain a certain control over Spoleto and Benevento, and, taking advantage of the disagreements between the Pope and Byzantium concerning the reverence of icons, he annexed the Exarchate of Ravenna and the duchy of Rome. He also helped the Frankish marshal Charles Martel drive back the Arabs. The Slavs were defeated in the Battle of Lavariano, when they tried to conquer the Friulian Plain in 720.[78] Liutprand's successor Aistulf conquered Ravenna for the Lombards for the first time but had to relinquish it when he was subsequently defeated by the king of the Franks, Pippin III, who was called by the Pope.

After the death of Aistulf, Ratchis attempted to become king of Lombardy, but he was deposed by Desiderius, duke of Tuscany, the last Lombard to rule as king. Desiderius managed to take Ravenna definitively, ending the Byzantine presence in northern Italy. He decided to reopen struggles against the Pope, who was supporting the dukes of Spoleto and Benevento against him, and entered Rome in 772, the first Lombard king to do so. But when Pope Hadrian I called for help from the powerful Frankish king Charlemagne, Desiderius was defeated at Susa and besieged in Pavia, while his son Adelchis was forced to open the gates of Verona to Frankish troops. Desiderius surrendered in 774, and Charlemagne, in an utterly novel decision, took the title "King of the Lombards". Before then the Germanic kingdoms had frequently conquered each other, but none had adopted the title of King of another people. Charlemagne took part of the Lombard territory to create the Papal States.

The Lombardy region in Italy, which includes the cities of Brescia, Bergamo, Milan, and the old capital Pavia, is a reminder of the presence of the Lombards.

Later history

Falling to the Franks and the Duchy of Benevento, 774–849

Though the kingdom centred on Pavia in the north fell to Charlemagne and the Franks in 774, the Lombard-controlled territory to the south of the Papal States was never subjugated by Charlemagne or his descendants. In 774, Duke Arechis II of Benevento, whose duchy had only nominally been under royal authority, though certain kings had been effective at making their power known in the south, claimed that Benevento was the successor state of the kingdom. He tried to turn Benevento into a secundum Ticinum: a second Pavia. He tried to claim the kingship, but with no support and no chance of a coronation in Pavia.

Charlemagne came down with an army, and his son Louis the Pious sent men, to force the Beneventan duke to submit, but his submission and promises were never kept and Arechis and his successors were de facto independent. The Beneventan dukes took the title prínceps (prince) instead of that of king.

The Lombards of southern Italy were thereafter in the anomalous position of holding land claimed by two empires: the Carolingian Empire to the north and west and the Byzantine Empire to the east. They typically made pledges and promises of tribute to the Carolingians, but effectively remained outside Frankish control. Benevento meanwhile grew to its greatest extent yet when it imposed a tribute on the Duchy of Naples, which was tenuously loyal to Byzantium and even conquered the Neapolitan city of Amalfi in 838. At one point in the reign of Sicard, Lombard control covered most of southern Italy save the very south of Apulia and Calabria and Naples, with its nominally attached cities. It was during the 9th century that a strong Lombard presence became entrenched in formerly Greek Apulia. However, Sicard had opened up the south to the invasive actions of the Saracens in his war with Andrew II of Naples and when he was assassinated in 839, Amalfi declared independence and two factions fought for power in Benevento, crippling the principality and making it susceptible to external enemies.

The civil war lasted ten years and ended with a peace treaty imposed in 849 by Emperor Louis II, the only Frankish king to exercise actual sovereignty over the Lombard states. The treaty divided the kingdom into two states: the Principality of Benevento and the Principality of Salerno, with its capital at Salerno on the Tyrrhenian Sea.

Southern Italy and the Arabs, 836–915

Andrew II of Naples hired Islamic mercenaries and formed a Muslim-Christian alliance for his war with Sicard of Benevento in 836; Sicard responded with other Muslim mercenaries. The Saracens initially concentrated their attacks on Sicily and Byzantine Italy, but soon Radelchis I of Benevento called in more mercenaries, who destroyed Capua in 841. Landulf the Old founded the present-day Capua, "New Capua", on a nearby hill. In general, the Lombard princes were less inclined to ally with the Saracens than with their Greek neighbours of Amalfi, Gaeta, Naples, and Sorrento. Guaifer of Salerno, however, briefly put himself under Muslim suzerainty.

In 847 a large Muslim force seized Bari, until then a Lombard gastaldate under the control of Pandenulf. Saracen incursions proceeded northwards until Adelchis of Benevento sought the help of his suzerain, Louis II, who allied with the Byzantine emperor Basil I to expel the Arabs from Bari in 869. An Arab landing force was defeated by the emperor in 871. Adelchis and Louis remained at war until the death of Louis in 875. Adelchis regarded himself as the true successor of the Lombard kings, and in that capacity he amended the Edictum Rothari, the last Lombard ruler to do so.

After the death of Louis, Landulf II of Capua briefly flirted with a Saracen alliance, but Pope John VIII convinced him to break it off. Guaimar I of Salerno fought the Saracens with Byzantine troops. Throughout this period the Lombard princes swung in allegiance from one party to another. Finally, towards 915, Pope John X managed to unite the Christian princes of southern Italy against the Saracen establishments on the Garigliano river. The Saracens were ousted from Italy in the Battle of the Garigliano in 915.

Lombard principalities in the 10th century

The independent state of Salerno inspired the gastalds of Capua to move towards independence, and by the end of the century they were styling themselves "princes" and as a third Lombard state. The Capuan and Beneventan states were united by Atenulf I of Capua in 900. He subsequently declared them to be in perpetual union, and they were separated only in 982, on the death of Pandulf Ironhead. With all of the Lombard south under his control, except Salerno, Atenulf felt safe to use the title Princeps Gentis Langobardorum ("prince of the Lombard people"), which Arechis II had begun using in 774. Among Atenulf's successors the principality was ruled jointly by fathers, sons, brothers, cousins, and uncles for the greater part of the century. Meanwhile, the prince Gisulf I of Salerno began using the title Langobardorum Gentis Princeps around mid-century, but the ideal of a united Lombard principality was realised only in December 977, when Gisulf died and his domains were inherited by Pandulf Ironhead, who temporarily held almost all Italy south of Rome and brought the Lombards into alliance with the Holy Roman Empire. His territories were divided upon his death.

Landulf the Red of Benevento and Capua tried to conquer the principality of Salerno with the help of John III of Naples, but with the aid of Mastalus I of Amalfi, Gisulf repulsed him. The rulers of Benevento and Capua made several attempts on Byzantine Apulia at this time, but late in the century, the Byzantines, under the stiff rule of Basil II, gained ground on the Lombards.

The principal source for the history of the Lombard principalities in this period is the Chronicon Salernitanum, composed late in the 10th century at Salerno.

Norman conquest, 1017–1078

The diminished Beneventan principality soon lost its independence to the papacy and declined in importance until it fell in the Norman conquest of southern Italy. The Normans, first called in by the Lombards to fight the Byzantines for control of Apulia and Calabria (under the likes of Melus of Bari and Arduin, among others), had become rivals for hegemony in the south. The Salernitan principality experienced a golden age under Guaimar III and Guaimar IV, but under Gisulf II, the principality shrank to insignificance and fell in 1078 to Robert Guiscard, who had married Gisulf's sister Sichelgaita. The Capua principality was hotly contested during the reign of the hated Pandulf IV, the Wolf of the Abruzzi, and, under his son, it fell, almost without contest, to the Norman Richard Drengot (1058). The Capuans revolted against Norman rule in 1091, expelling Richard's grandson Richard II and setting up one Lando IV.

Capua was again put under Norman rule after the Siege of Capua of 1098 and the city quickly declined in importance under a series of ineffectual Norman rulers. The independent status of these Lombard states is in general attested by the ability of their rulers to switch suzerains at will. Often the legal vassal of pope or emperor (either Byzantine or Holy Roman), they were the real power-brokers in the south until their erstwhile allies, the Normans, rose to preeminence: The Lombards regarded the Normans as barbarians and the Byzantines as oppressors. Regarding their own civilisation as superior, the Lombards did indeed provide the environment for the illustrious Schola Medica Salernitana.

Physical anthropology

Physical anthropologists have found striking similarities between Lombard skeletons and the skeletons of the contemporary population of the Swedish island of Gotland. This evidence suggest a Scandinavian origin for the Lombards.[80]

Genetics

A genetic study published in Nature Communications in September 2018 found strong genetic similarities between Lombards of Italy and earlier Lombards of Central Europe. The Lombards of Central Europe displayed no genetic similarities with earlier populations of this region, but were on the other hand strikingly similar genetically to Bronze Age Scandinavians. Lombard males were primarily carriers of subclades of haplogroup R1b and I2a2a1, both of whom are common among Germanic peoples. Lombard males were found to be more genetically homogenous than Lombard females. The evidence suggested that the Lombards originated in Northern Europe, and were a patriarchal people who settled Central Europe and then later Italy through a migration from the north.[15][81]

A genetic study published in Science Advances in September 2018 examined the remains of a Lombard male buried at an Alemannic graveyard. He was found to be a carrier of the paternal haplogroup R1b1a2a1a1c2b2b and the maternal haplogroup H65a. The graveyard also included the remains of a Frankish and a Byzantine male, both of whom were also carriers of subclades of the paternal haplogroup R1b1a2a1a1. The Lombard, Frankish and Byzantine males were all found to be closely related, and displayed close genetic links to Northern Europe, particularly Lithuania and Iceland.[82]

A genetic study published in the American Journal of Physical Anthropology in September 2018 examined the mtDNA of remains from various periods in Italian history, including the Lombard period. The evidence collected suggested that the Lombards were an endogameous elite community who did not leave much of an imprint on the maternal ancestry of the Italian population.[83]

A genetic study published in the European Journal of Human Genetics in January 2019 examined the mtDNA of a large number of early medieval Lombard remains from Central Europe and Italy. These individuals were found to be closely related and displayed strong genetic links to Northern Europe. The evidence suggested that the Lombard settlement of Italy was the result of a migration from the north involving both males and females.[16]

Culture

Language

The Lombardic language is extinct (unless Cimbrian and Mocheno represent surviving dialects).[84] The Germanic language declined, beginning in the 7th century, but may have been in scattered use until as late as about the year 1000. Only fragments of the language have survived, the main evidence being individual words quoted in Latin texts. In the absence of Lombardic texts, it is not possible to draw any conclusions about the language's morphology and syntax. The genetic classification of the language depends entirely on phonology. Since there is evidence that Lombardic participated in, and indeed shows some of the earliest evidence for, the High German consonant shift, it is usually classified as an Elbe Germanic or Upper German dialect.[85]

Lombardic fragments are preserved in runic inscriptions. Primary source texts include short inscriptions in the Elder Futhark, among them the "bronze capsule of Schretzheim" (c. 600) and the silver belt buckle found in Pforzen, Ostallgäu (Schwaben). A number of Latin texts include Lombardic names, and Lombardic legal texts contain terms taken from the legal vocabulary of the vernacular. In 2005, Emilia Denčeva argued that the inscription of the Pernik sword may be Lombardic.[86]

The Italian language preserves a large number of Lombardic words, although it is not always easy to distinguish them from other Germanic borrowings such as those from Gothic or from Frankish. They often bear some resemblance to English words, as Lombardic was akin to Old Saxon.[87] For instance, landa from land, guardia from wardan (warden), guerra from werra (war), ricco from rikki (rich), and guadare from wadjan (to wade).

From the Codice diplomatico longobardo, a collection of legal documents that makes reference to many Lombardic terms, we obtain several terms still in use in the Italian language:

barba (beard), marchio (mark), maniscalco (blacksmith), aia (courtyard), braida (suburban meadow), borgo (burg, village), fara (fundamental unity of Lombard social and military organization, presently used as toponym), pizzo (peak, mountain top, now used as toponym), sala (hall, room, also used as toponym), staffa (stirrup), stalla (stable), sculdascio, faida (feud), manigoldo (scoundrel), sgherro (henchman); fanone (baleen), stamberga (hovel); anca (hip), guancia (cheek), nocca (knuckle), schiena (back); gazza (magpie), martora (marten); gualdo (wood, presently used as toponym), pozza (pool); verbs like bussare (to knock), piluccare (to peck), russare (to snore).

Social structure

Migration Period society

During their stay at the mouth of the Elbe, the Lombards came into contact with other western Germanic populations, such as the Saxons and the Frisians. From these populations, which for long had been in contact with the Celts (especially the Saxons), they learned a rigid social organization into castes, rarely present in other Germanic peoples.[88]

The Lombard kings can be traced back as early as c. 380 and thus to the beginning of the Great Migration. Kingship developed amongst the Germanic peoples when the unity of a single military command was found necessary. Schmidt believed that the Germanic tribes were divided according to cantons and that the earliest government was a general assembly that selected canton chiefs and war leaders in times of conflict. All such figures were probably selected from a caste of nobility. As a result of the wars of their wanderings, royal power developed such that the king became the representative of the people, but the influence of the people on the government did not fully disappear.[89] Paul the Deacon gives an account of the Lombard tribal structure during the migration:

. . . in order that they might increase the number of their warriors, [the Lombards] confer liberty upon many whom they deliver from the yoke of bondage, and that the freedom of these may be regarded as established, they confirm it in their accustomed way by an arrow, uttering certain words of their country in confirmation of the fact.

Complete emancipation appears to have been granted only among the Franks and the Lombards.[90]

Society of the Catholic kingdom

Lombard society was divided into classes comparable to those found in the other Germanic successor states of Rome, Frankish Gaul and Visigothic Spain. There was a noble class, a class of free persons beneath them, a class of unfree non-slaves (serfs), and finally slaves. The aristocracy itself was poorer, more urbanised, and less landed than elsewhere. Aside from the richest and most powerful of the dukes and the king himself, Lombard noblemen tended to live in cities (unlike their Frankish counterparts) and hold little more than twice as much in land as the merchant class (a far cry from provincial Frankish aristocrats who held vast swathes of land, hundreds of times larger than those beneath his status). The aristocracy by the 8th century was highly dependent on the king for means of income related especially to judicial duties: many Lombard nobles are referred to in contemporary documents as iudices (judges) even when their offices had important military and legislative functions as well.

The freemen of the Lombard kingdom were far more numerous than in Frank lands, especially in the 8th century, when they are almost invisible in surviving documentary evidence. Smallholders, owner-cultivators, and rentiers are the most numerous types of person in surviving diplomata for the Lombard kingdom. They may have owned more than half of the land in Lombard Italy. The freemen were exercitales and viri devoti, that is, soldiers and "devoted men" (a military term like "retainers"); they formed the levy of the Lombard army, and they were sometimes, if infrequently, called to serve, though this seems not to have been their preference. The small landed class, however, lacked the political influence necessary with the king (and the dukes) to control the politics and legislation of the kingdom. The aristocracy was more thoroughly powerful politically if not economically in Italy than in contemporary Gaul and Spain.

The urbanisation of Lombard Italy was characterised by the città ad isole (or "city as islands"). It appears from archaeology that the great cities of Lombard Italy — Pavia, Lucca, Siena, Arezzo, Milan — were themselves formed of minute islands of urbanisation within the old Roman city walls. The cities of the Roman Empire had been partially destroyed in the series of wars of the 5th and 6th centuries. Many sectors were left in ruins and ancient monuments became fields of grass used as pastures for animals, thus the Roman Forum became the Campo Vaccino, the field of cows. The portions of the cities that remained intact were small, modest, contained a cathedral or major church (often sumptuously decorated), and a few public buildings and townhomes of the aristocracy. Few buildings of importance were stone, most were wood. In the end, the inhabited parts of the cities were separated from one another by stretches of pasture even within the city walls.

Lombard states

- Lombard state on the Carpathians (6th century)

- Lombard state in Pannonia (6th century)

- Kingdom of Italy and List of Kings of the Lombards

- Principality of Benevento and List of Dukes and Princes of Benevento

- Principality of Salerno and List of Princes of Salerno

- Principality of Capua and List of Princes of Capua

Religious history

The legend from Origo may hint that initially, before the passage from Scandinavia to the southern coast of the Baltic Sea, the Lombards worshiped the Vanir. Later, in contact with other Germanic populations, they adopted the worship of the Æsir: an evolution that marked the passage from the adoration of deities related to fertility and the earth to the cult of warlike gods.[91][92]

In chapter 40 of his Germania, Roman historian Tacitus, discussing the Suebian tribes of Germania, writes that the Lombards were one of the Suebian tribes united in worship of the deity Nerthus, who is often identified with the Norse goddess Freyja. The other tribes were the Reudigni, Aviones, Anglii, Varini, Eudoses, Suarines and Nuitones.[93]

St. Barbatus of Benevento observed many pagan rituals and traditions amongst the Lombards authorised by the Duke Romuald, son of King Grimoald:[94]

They expressed a religious veneration to a golden viper, and prostrated themselves before it: they paid also a superstitious honour to a tree, on which they hung the skin of a wild beast, and these ceremonies were closed by public games, in which the skin served for a mark at which bowmen shot arrows over their shoulder.

Christianisation

The Lombards were first touched by Christianity while still in Pannonia, but only touched: their conversion and Christianisation was largely nominal and far from complete. During the reign of Wacho, they were Orthodox Catholics allied with the Byzantine Empire, but Alboin converted to Arianism as an ally of the Ostrogoths and invaded Italy. All these Christian conversions primarily affected the aristocracy, while the common people remained pagan.

In Italy, the Lombards were intensively Christianised, and the pressure to convert to Catholicism was great. With the Bavarian queen Theodelinda, a Catholic, the monarchy was brought under heavy Catholic influence. After initial support for the anti-Rome party in the Schism of the Three Chapters, Theodelinda remained a close contact and supporter of Pope Gregory I. In 603, Adaloald, the heir to the throne, received Catholic baptism. During the next century, Arianism and paganism continued to hold out in Austria (the northeast of Italy) and in the Duchy of Benevento. A succession of Arian kings was militarily aggressive and presented a threat to the Papacy in Rome. In the 7th century, the nominally Christian aristocracy of Benevento was still practising pagan rituals such as sacrifices in "sacred" woods. By the end of the reign of Cunincpert, however, the Lombards were more or less completely Catholicised. Under Liutprand Catholicism became tangible as the king sought to justify his title rex totius Italiae by uniting the south of the peninsula with the north, thereby bringing together his Italo-Roman and Germanic subjects into one Catholic State.

Beneventan Christianity

The Duchy and eventually Principality of Benevento in southern Italy developed a unique Christian rite in the 7th and 8th centuries. The Beneventan rite is more closely related to the liturgy of the Ambrosian rite than to the Roman rite. The Beneventan rite has not survived in its complete form, although most of the principal feasts and several feasts of local significance are extant. The Beneventan rite appears to have been less complete, less systematic, and more liturgically flexible than the Roman rite.

Characteristic of this rite was the Beneventan chant, a Lombard-influenced chant that bore similarities to the Ambrosian chant of Milan. The Beneventan chant is largely defined by its role in the liturgy of the Beneventan rite; many Beneventan chants were assigned multiple roles when inserted into Gregorian chantbooks, appearing variously as antiphons, offertories, and communions, for example. It was eventually supplanted by the Gregorian chant in the 11th century.

The chief centre of the Beneventan chant was Montecassino, one of the first and greatest abbeys of Western monasticism. Gisulf II of Benevento had donated a large swathe of land to Montecassino in 744, and that became the basis for an important state, the Terra Sancti Benedicti, which was a subject only to Rome. The Cassinese influence on Christianity in southern Italy was immense. Montecassino was also the starting point for another characteristic of Beneventan monasticism, the use of the distinct Beneventan script, a clear, angular script derived from the Roman cursive as used by the Lombards.

Art

During their nomadic phase, the Lombards primarily created art that was easily carried with them, like arms and jewellery. Though relatively little of this has survived, it bears resemblance to the similar endeavours of other Germanic tribes of northern and central Europe from the same era.

The first major modifications to the Germanic style of the Lombards came in Pannonia and especially in Italy, under the influence of local, Byzantine, and Christian styles. The conversions from nomadism and paganism to settlement and Christianity also opened up new arenas of artistic expression, such as architecture (especially churches) and its accompanying decorative arts (such as frescoes).

Lombard shield boss

Lombard shield boss

northern Italy, 7th century, Metropolitan Museum of Art Lombard S-shaped fibula

Lombard S-shaped fibula- A glass drinking horn from Castel Trosino

Lombard Goldblattkreuz

Lombard Goldblattkreuz Lombard fibulae

Lombard fibulae- Altar of Ratchis

8th-century Lombard sculpture depicting female martyrs, based on a Byzantine model. Tempietto Longobardo, Cividale del Friuli

8th-century Lombard sculpture depicting female martyrs, based on a Byzantine model. Tempietto Longobardo, Cividale del Friuli

Architecture

Few Lombard buildings have survived. Most have been lost, rebuilt, or renovated at some point, so they preserve little of their original Lombard structure. Lombard architecture was well-studied in the 20th century, and the four-volume Lombard Architecture (1919) by Arthur Kingsley Porter is a "monument of illustrated history".

The small Oratorio di Santa Maria in Valle in Cividale del Friuli is probably one of the oldest preserved examples of Lombard architecture, as Cividale was the first Lombard city in Italy. Parts of Lombard constructions have been preserved in Pavia (San Pietro in Ciel d'Oro, crypts of Sant'Eusebio and San Giovanni Domnarum) and Monza (cathedral). The Basilic autariana in Fara Gera d'Adda near Bergamo and the church of San Salvatore in Brescia also have Lombard elements. All these buildings are in northern Italy (Langobardia major), but by far the best-preserved Lombard structure is in southern Italy (Langobardia minor). The Church of Santa Sofia in Benevento was erected in 760 by Duke Arechis II, and it preserves Lombard frescoes on the walls and even Lombard capitals on the columns.

Lombard architecture flourished under the impulse provided by the Catholic monarchs like Theodelinda, Liutprand, and Desiderius to the foundation of monasteries to further their political control. Bobbio Abbey was founded during this time.

Some of the late Lombard structures of the 9th and 10th centuries have been found to contain elements of style associated with Romanesque architecture and have been so dubbed "first Romanesque". These edifices are considered, along with some similar buildings in southern France and Catalonia, to mark a transitory phase between the Pre-Romanesque and full-fledged Romanesque.

List of rulers

Notes and sources

Notes

- "Lombard". Collins English Dictionary.

- Priester, 16. From Proto-Germanic winna-, meaning "to fight, win".

- Harrison, D.; Svensson, K. (2007). Vikingaliv Fälth & Hässler, Värnamo. ISBN 978-91-27-35725-9 p. 74

- https://www.eupedia.com/genetics/italian_dna.shtml

- 2. Runriket - Täby Kyrka Archived 2008-06-04 at the Wayback Machine, an online article at Stockholm County Museum, retrieved July 1, 2007.

- Christie 1995, p. 3.

- Sergent, Bernard (1991). "Ethnozoonymes indo-européens". Dialogues d'histoire ancienne. 17 (2): 15. doi:10.3406/dha.1991.1932.

- Christie 2018, pp. 920-922.

- Christie 1995. "The Lombards, also known as the Longobards, were a Germanic tribe whose fabled origins lay in the barbarian realm of Scandinavia."

- Whitby 2012, p. 857. "Lombards, or Langobardi, a Germanic group..."

- Brown 2005. "Lombards... a west-Germanic people..."

- Darvill 2009. "Lombards (Lombard). Germanic people..."

- Taviani-Carozzi 2005. "Lombards, A people of Germanic origin, conquerors of part of Italy from 568."

- Christie 1995, pp. 1-6.

- Amorim 2018a. "Late Bronze Age Hungarians show almost no resemblance to populations from modern central/northern Europe, especially compare to Bronze Age Germans and in particular Scandinavians, who, in contrast, show considerable overlap with our Szólád and Collegno central/northern ancestry samples... Our results are thus consistent with an origin of barbarian groups such as the Longobards somewhere in Northern and Central Europe..."

- Vai 2019. "[T]he presence in this cluster of haplogroups that reach high frequency in Northern European populations, suggests a possible link between this core group of individuals and the proposed homeland of different ancient barbarian Germanic groups... This supports the view that the spread of Longobards into Italy actually involved movements of people, who gave a substantial contribution to the gene pool of the resulting populations...This is even more remarkable thinking that, in many studied cases, military invasions are movements of males, and hence do not have consequences at the mtDNA level. Here, instead, we have evidence of maternally linked genetic similarities between LC in Hungary and Italy, supporting the view that immigration from Central Europe involved females as well as males."

- CG, II.

- Menghin, 13.

- Priester, 16. Grimm, Deutsche Mythologie, I, 336. Old Germanic for "Strenuus", "Sibyl".

- Ibor and Aio were called by Prosper of Aquitaine, Iborea and Agio; Saxo-Grammaticus calls them Ebbo and Aggo; the popular song of Gothland (Bethmann, 342), Ebbe and Aaghe (Wiese, 14).

- Priester, 16

- Hammerstein-Loxten, 56.

- PD, VII.

- PD, VIII.

- OGL, appendix 11.

- Priester, 17

- PD, I, 9.

- Nedoma, Robert (2005).Der altisländische Odinsname Langbarðr: ‘Langbart’ und die Langobarden. In Pohl, Walter and Erhart, Peter, eds. Die Langobarden. Herrschaft und Identität. Wien. pp. 439–444

- Priester, 17.

- Fröhlich, 19.

- Bruckner, 30–33.

- The article Hadubarder in Nordisk familjebok (1909).

- Wilson Chambers, Raymond (2010). Widsith: A Study in Old English Heroic Legend. Cambridge University Press. p. 205.

- Smith’s Dict. of Greek and Roman Geogr., vol. ii. p. 119 — S.

- Orosius (1773). The Anglo-Saxon Version, from the Historian Orosius, by Ælfred the Great together with an English Translation from the Anglo-Saxon. Translated by Daines Barrington (Alfred the Great ed.). London: Printed by W. Bowyer and J. Nichols and sold by S. Baker. p. 256. Retrieved 7 May 2020.

- Widsith, lines 31-33

- Menghin, 15.

- Velleius, Hist. Rom. II, 106. Schmidt, 5.

- Strabo, VII, 1, 3.

- Suetoniu, The Twelve Caesars, chapters II and III.

- Wegewitz, Das langobardische Brandgräberfeld von Putensen, Kreis Harburg (1972), 1–29. Problemi della civilita e dell'economia Longobarda, Milan (1964), 19ff.

- Menghin, 17.

- Menghin, 18.

- Priester, 18.

- Tacitus, Ann. II, 45.

- Tacitus, Annals, XI, 16, 17.

- Cassius Dio, 71, 3, 1. Menghin 16.

- Priester, 21. Zeuss, 471. Wiese, 38. Schmidt, 35–36.

- Tacitus, Germania, 38-40

- Ptolemy, Geogr. II, 11, 9. Menghin, 15.

- Ptolemy, Geogr. II, 11, 17. Menghin, 15

- Schütte, Ptolemy's Maps of Northern Europe, pages 34, and 118

- Codex Gothanus, II.

- Priester, 14. Menghin, 16.

- Hartmann, II, pt I, 5.

- Menghin, 17, 19. Codex Gothanus, II.

- Zeuss, 471. Wiese, 38. Schmidt, 35–36. Priester, 21–22. HGL, X.

- Hammerstein-Loxten, 56. Bluhme. HGL, XIII.

- Cosmographer of Ravenna, I, 11.

- Hodgkin, Ch. V, 92. HGL, XII.

- Schmidt, 49.

- Hodgkin, V, 143.

- Menghin, Das Reich an der Donau, 21.

- K. Priester, 22.

- Bluhme, Gens Langobardorum Bonn, 1868

- Menghin, 14.

- Hist. gentis Lang., Ch. XVII

- Hist. gentis Lang., Ch. XVII.

- PD, XVII.

- Helmolt, Hans Ferdinand (1907). Battles The World's History: Central and northern Europe. London.

- Peters, Edward (2003). History of the Lombards: Translated by William Dudley Foulke. University of Pennsylvania Press.

- Ibid., 2.7.

- Ibid., 2.26.

- Paolo Diacono, Historia Langobardorum, FV, II, 4, 6, 7.

- De Bello Gothico IV 32, pp. 241-245

- "The New Cambridge Medieval History: c. 500-c. 700" by Paul Fouracre and Rosamond McKitterick (page 8)

- Lot, Ferdinand (1931). The End of the Ancient World and the Beginnings of the Middle Ages. London.

- Vidmar, Jernej. "Od kod prihajajo in kdo so solkanski Langobardi" [From Where Come and Who Are the Solkan Lombards] (in Slovenian). Retrieved 30 July 2012.

- Štih, Peter; Simoniti, Vasko; Vodopivec, Peter (2008). "The Settlement of the Slavs". In Lazarević, Žarko (ed.). A Slovene history: society – politics – culture. Ljubljana: Institute of Modern History. p. 22. ISBN 978-961-6386-19-7.

- Christie 1995, pp. 3-4.

- Amorim 2018b. "[B]iological relationships played an important role in these early medieval societies... Finally, our data are consistent with the proposed long-distance migration from Pannonia to Northern Italy."

- O'Sullivan 2018. "Niederstotzingen North individuals are closely related to northern and eastern European populations, particularly from Lithuania and Iceland."

- Leonardi 2018.

- Kortmann, Bernd (2011). The Languages and Linguistics of Europe: Vol.II. Berlin.

- Marcello Meli, Le lingue germaniche, p. 95.

- Emilia Denčeva (2006). "Langobardische (?) Inschrift auf einem Schwert aus dem 8. Jahrhundert in bulgarischem Boden" (PDF). Beiträge zur Geschichte der deutschen Sprache und Literatur. 128 (1): 1-11. doi:10.1515/BGSL.2006.1

- Hutterer 1999, p. 339.

- Cardini-Montesano, cit., pag. 82.

- Schmidt, 76–77.

- Schmidt, 47 n3.

- Rovagnati, p. 99.

- Karl Hauk, Lebensnormen und Kultmythen in germanischen Sammes- und Herrscher genealogien.

- Tacitus', Germania, 40, Medieval Source Book. Code and format by Northvegr. Archived 2008-04-04 at the Wayback Machine

- Rev. Butler, Alban (1866). The Lives of the Fathers, Martyrs, and Other Principal Saints: Vol.I. London.

Ancient sources

- Cosmographer of Ravenna

- Historia Langobardorum Codicis Gothani in Codex Gothanus

- Historia Langobardorum

- Origo Gentis Langobardorum

- Tacitus. Annals

- Tacitus. Germania

Modern sources

- Amorim, Carlos Eduardo G. (February 20, 2018a). "Understanding 6th-Century Barbarian Social Organization and Migration through Paleogenomics". 9 (3547). bioRxiv 10.1101/268250. doi:10.1101/268250. Retrieved March 13, 2020. Cite journal requires

|journal=(help)CS1 maint: ref=harv (link) - Amorim, Carlos Eduardo G. (September 11, 2018b). "Understanding 6th-century barbarian social organization and migration through paleogenomics". Nature Communications. Nature Research. 9 (3547). doi:10.1038/s41467-018-06024-4. PMC 6134036. PMID 30206220. Retrieved March 13, 2020.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Bluhme, Friedrich (1868). Die Gens Langobardorum und ihre Herkunft, ...und ihre Sprache. Bonn: A.Marcus.

- Brown, Thomas S. (2005). "Lombards". In Kazhdan, Alexander P. (ed.). The Oxford Dictionary of Byzantium. Oxford University Press. ISBN 9780195187922. Retrieved January 26, 2020.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Bruckner, Wilhelm (1895). Die Sprache der Langobarden, Quellen und Forschungen zur Sprach- und Culturgeschichte der germanischen Völker, 75. Strassburg: Karl J. Trübner.

- Christie, Neil (1995). The Lombards. Wiley. ISBN 0631182381.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Christie, Neil (2018). "Lomvard Invasion Of Italy". In Nicholson, Oliver (ed.). The Oxford Dictionary of Late Antiquity. Oxford University Press. pp. 919–920. doi:10.1093/acref/9780198662778.001.0001. ISBN 9780191744457. Retrieved March 13, 2020.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Christie, Neil (2018). "Lombards". In Nicholson, Oliver (ed.). The Oxford Dictionary of Late Antiquity. Oxford University Press. pp. 920–922. doi:10.1093/acref/9780198662778.001.0001. ISBN 9780191744457. Retrieved March 13, 2020.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Darvill, Timothy (2009). "Lombards". The Concise Oxford Dictionary of Archaeology (3 ed.). Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/acref/9780199534043.001.0001. ISBN 9780191727139. Retrieved January 25, 2020.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Everett, Nicholas (2003). Literacy in Lombard Italy, c. 568-774. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 9780521819053.

- Fröhlich, Hermann (1976). "Zur Herkunft der Langobarden". In Quellen und Forschungen aus italienischen Archiven und Bibliotheken (QFIAB) 55/56. Tübingen : Max Niemeyer. pp. 1–21.

- Fröhlich, Hermann (1980). Studien zur langobardischen Thronfolge. In two volumes. Diss. Eberhard-Karls-Universität zu Tübingen.

- Giess, Hildegard. "The Sculpture of the Cloister of Santa Sofia in Benevento",The Art Bulletin, Vol. 41, No. 3. (September 1959), pp 249–256.

- Grimm, Jacob (1875–78) [1st ed. 1835]. Deutsche Mythologie

- Gwatkin, H. M., Whitney, J. P. (ed) (1913). The Cambridge Medieval History: Volume II—The Rise of the Saracens and the Foundations of the Western Empire.

- Hallenbeck, Jan T (1982). Pavia and Rome: The Lombard Monarchy and the Papacy in the Eighth Century. Transactions of the American Philosophical Society, vol.74 — New Series, part 4. Philadelphia.

- Hammerstein-Loxten, Wilhelm Freiherr von (1869). Die Bardengau. Hannover: Hahn'sche Buchhandlung.

- Hartmann, Ludo Moritz. Geschichte Italiens im Mittelalter II Vol.

- Hodgkin, Thomas. Italy and Her Invaders. Clarendon Press

- Leonardi, Michela (September 6, 2018). "The female ancestor's tale: Long‐term matrilineal continuity in a nonisolated region of Tuscany". American Journal of Physical Anthropology. Wiley. 167 (3): 497–506. bioRxiv 10.1101/268250. doi:10.1002/ajpa.23679. PMID 30187463. Retrieved March 13, 2020.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Menghin, Wilifred. Die Langobarden / Geschichte und Archäologie. Theiss

- O'Sullivan, Niall (September 9, 2018). "Ancient genome-wide analyses infer kinship structure in an Early Medieval Alemannic graveyard". Science Advances. American Association for the Advancement of Science. 4 (9). doi:10.1126/sciadv.aao1262. PMC 6124919. PMID 30191172. Retrieved March 13, 2020.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Oman, Charles (1914) [1893] . The Dark Ages 476–918 (6th ed.). Periods of European History. London: Rivingtons.

- Pohl, Walter and Erhart, Peter (2005). Die Langobarden : Herrschaft und Identität. Forschungen zur Geschichte des Mittelalters, 9. Wien: VÖAW.

- Priester, Karin (2004). Geschichte der Langobarden: Gesellschaft – Kultur – Altagsleben. Stuttgart: Konrad Theiss.

- The Lombard Laws. Translated by Katherine Fischer Drew. foreword by Edward Peters. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press. 1973. ISBN 0-8122-1055-7.CS1 maint: others (link)

- Santosuosso, Antonio (2004). Barbarians, Marauders, and Infidels: The Ways of Medieval Warfare. ISBN 0-8133-9153-9

- Schmidt, Dr. Ludwig (1885). Zur Geschichte der Langobarden. Leipzig: Gustav Fock. Also in (1884) Älteste Geschichte der Langobarden. Ein Beitrag zur Geschichte der Völkerwanderung. Dissertation. Leipzig, Universität.

- Todd, Malcolm (2004). The Early Germans. Wiley. ISBN 9781405117142.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Wegewitz, Willi. Das langobardische Brandgräberfeld von Putensen, Kreise Harburg

- Wickham, Christopher (1998). "Aristocratic Power in Eighth-Century Lombard Italy". In Goffart, Walter A.; Murray, Alexander C. (eds.). After Rome's Fall: Narrators and Sources of Early Medieval History, Essays presented to Walter Goffart. Toronto: University of Toronto Press. pp. 153–170. ISBN 0-8020-0779-1..

- Wiese, Robert. Die älteste Geschichte der Langobarden

- Zeuss, Kaspar. Die Deutschen und die Nachbarstämme

- Carlo Troya, Giovanni Minervini (1852-1855) Codice diplomatico longobardo dal DLXVIII al DCCLXXIV: con note storiche, Napoli, Stamperia reale, 1855

- Hutterer, Claus Jürgen (1999). "Langobardisch". Die Germanischen Sprachen. Wiesbaden: Albus. pp. 336–341. ISBN 3-928127-57-8.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Taviani-Carozzi, Huguette (2005). "Lombards". In Vauchez, André (ed.). Encyclopedia of the Middle Ages. James Clarke & Co. doi:10.1093/acref/9780227679319.001.0001. ISBN 9780195188172. Retrieved January 26, 2020.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Vai, Stefania (January 19, 2019). "A genetic perspective on Longobard-Era migrations". European Journal of Human Genetics. Nature Research. 27: 647–656. doi:10.1038/s41431-018-0319-8. PMC 6460631. PMID 30651584. Retrieved March 13, 2020.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Whitby, L. Michael (2012). "Lombards". In Hornblower, Simon; Spawforth, Antony; Eidinow, Esther (eds.). The Oxford Classical Dictionary (4 ed.). Oxford University Press. p. 857. doi:10.1093/acref/9780199545568.001.0001. ISBN 9780191735257. Retrieved January 25, 2020.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

External links

![]()

- Beck, Frederick George Meeson; Church, Richard William (1911). . Encyclopædia Britannica (11th ed.).

_-_Foto_Giovanni_Dall'Orto%2C_13-mar-2012.jpg)