Vyasa

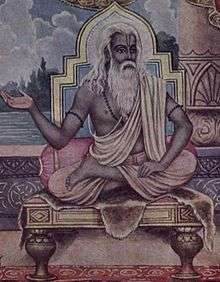

Vyasa (/ˈvjɑːsə/; Sanskrit: व्यासः, literally "Compiler") is the legendary author of the Mahabharata, Vedas and Puranas, some of the most important works in the Hindu tradition. He is also called Veda Vyāsa (वेदव्यासः, veda-vyāsaḥ, "the one who classified the Vedas") or Krishna Dvaipāyana (referring to his dark complexion and birthplace).

| Vyasa | |

|---|---|

| |

| Festivals | Festival of Guru Purnima, is dedicated to him, and also known as the Vyasa Purnima |

| Personal information | |

| Parents | |

| Spouse | Pinjalaa |

| Children | Dhritarashtra, Pandu, Vidura, Shuka |

The festival of Guru Purnima is dedicated to him. It is also known as Vyasa Purnima, the day believed to be both of his birth and when he divided the Vedas.[1][2] Vyasa is considered one of the seven Chiranjivis (long-lived, or immortals), who are still in existence according to Hindu tradition.

Early life

| Part of a series on | |

| Hindu philosophy | |

|---|---|

| |

| Orthodox | |

|

|

|

| Heterodox | |

|

|

|

|

|

|

Vyasa appears for the first time as the compiler of, and an important character in, the Mahabharata. It is said that he was the expansion of the God Vishnu, who came in Dvapara Yuga to make all the Vedic knowledge from oral tradition available in written form. He was son of Satyavati, adopted daughter of the fisherman Dusharaj and the wandering sage Parashara, who is credited with being the author of the first Purana, Vishnu Purana. [3] He was born on an island in the river Yamuna.[4] Due to his dark complexion, Vyasa was also given the name Krishna, in addition to the name Dwaipayana, meaning "island-born". According to the Vishnu Purana, Vyasa was born on an island of the Yamuna at Kalpi.[5]

According to legend, in a previous life Vyasa was the Sage Apantaratamas, who was born when Lord Vishnu uttered the syllable "Bhu". He was a devotee of Lord Vishnu. Since birth, he already possessed the knowledge of the Vedas, the Dharmashastras and the Upanishads. At Vishnu's behest, he was reborn as Vyasa.

Vyasa was the son of Sage Parashara and great grandson of Sage Vashistha. Prior to Vyasa's birth, Parashara had performed a severe penance to Lord Shiva. Shiva granted a boon that Parashara's son would be a Brahmarshi equal to Vashistha and would be famous for his knowledge. Parashara begot Vyasa with Satyavati. She conceived and immediately gave birth to Vyasa. Vyasa became an adult and left, promising his mother that he would come to her when needed.

Vyasa acquired his knowledge from the four Kumaras, Narada and Lord Brahma himself.

Vyasa is believed to have lived on the banks of Ganga in modern-day Uttarakhand. The site was also the ritual home of the sage Vashishta, along with the Pandavas, the five brothers of the Mahabharata.[6]

Role In Mahabharata

According to the Mahabharata, the sage Vyasa was the son of Satyavati and Parashara. During her youth, Satyavati was a fisherwoman who used to drive a boat. One day, sage Parashara was in a hurry to attend a Yajna. Satyavati helped him cross the river borders. Parashara was enchanted by the beauty of Satyavati and wanted his heir from her. Initially she did not agree to his demand telling that other saints would see them, and her purity would be questioned. So Parashara created a secret place with bushes and Satyavati agreed. Satyavati later gave birth to Vyasa. Parashara took away Vyasa with him when he was born. She kept this incident a secret, not telling even King Shantanu whom she was married to later.

After many years, Shantanu and Satyavati had two sons, named Chitrangada and Vichitravirya. Chitrangada was killed by Gandharvas in a battle, while Vichitravirya was weak and ill all the time. Satyavati then asked Bhisma to fetch queens for Vichitravirya. Bhishma attended the swayamvara conducted by the king of Kashi (present-day Varanasi), and defeated all the kings. Amba openly rebuted the swayamvara as she was in love with the prince of shalva, which was against the rule of swayamvara. Later bhishma came to know that King of Kashi did not know about the love of his elder daughter, so Bhishma released Amba and allowed her to go to Shalva kingdom and marry the prince who later rejected her. She came back to Bhishma and asked him to marry her, which he could not due to his vow of life long celibacy. She shuttled between Bhishma and Shalva with no success. Due to this she vowed to kill Bhishma. During the wedding ceremony, Vichitravirya collapsed and died. Satyavati was clueless on how to save the clan from perishing. She asked Bhishma to marry both the queens, who refused citing his vow and the promise that he made to her and his father, never to marry. He, therefore, could not father an heir to the kingdom. Later, Satyavati revealed to Bhishma, secrets from her past life and requested him to bring Vyasa to Hastinapur.

Sage Vyasa had a fierce personality and a bright, glowing spiritual aura around him. Hence upon seeing him, Ambika who was rather scared shut her eyes, resulting in their child, Dhritarashtra, being born blind. The other queen, Ambalika, turned pale upon meeting Vyasa, which resulted in their child, Pandu, being born pale. Alarmed, Satyavati requested that Vyasa meet Ambika again and grant her another son. Ambika instead sent her maid to meet Vyasa. The duty-bound maid was calm and composed; she had a healthy child who was later named Vidura.

While these are Vyasa's sons, another son Shuka, born of his wife Pinjalā (Vatikā),[7] daughter of the sage Jābāli was his true spiritual heir. Shuka appears occasionally in the story as a spiritual guide to the young Kuru princes.

Veda Vyasa

Hindus traditionally hold that Vyasa categorised the primordial single Veda into three canonical collections and that the fourth one, known as Atharvaveda, was recognized as Veda only very much later. Hence he was called Veda Vyasa, or "Splitter of the Vedas," the splitting being a feat that allowed people to understand the divine knowledge of the Veda. The word vyasa means split, differentiate or describe.

The Vishnu Purana has a theory about Vyasa.[8] The Hindu view of the universe is that of a cyclic phenomenon that comes into existence and dissolves repeatedly. Each cycle is presided over by a number of Manus, one for each Manvantara, that has four ages, Yugas of declining virtues. The Dvapara Yuga is the third Yuga. The Vishnu Purana (Book 3, Ch 3) says:

In every third world age (Dvapara), Vishnu, in the person of Vyasa, in order to promote the good of mankind, divides the Veda, which is properly but one, into many portions. Observing the limited perseverance, energy and application of mortals, he makes the Veda fourfold, to adapt it to their capacities; and the bodily form which he assumes, in order to effect that classification, is known by the name of Veda-vyasa. Of the different Vyasas in the present Manvantara and the branches which they have taught, you shall have an account. Twenty-eight times have the Vedas been arranged by the great Rishis in the Vaivasvata Manvantara... and consequently eight and twenty Vyasas have passed away; by whom, in the respective periods, the Veda has been divided into four. The first... distribution was made by Svayambhu (Brahma) himself; in the second, the arranger of the Veda (Vyasa) was Prajapati... (and so on up to twenty-eight).[9]

As per Vishnu Purana, Guru Drona's son rishi Aswatthama will become the next sage (Vyasa) and will divide the Veda in 29th Maha Yuga of 7th Manvantara.[10]

Works

The Mahabharata

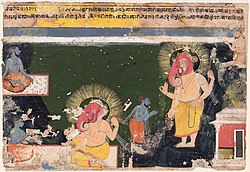

Vyasa is traditionally known as the chronicler of this epic and also features as an important character in Mahābhārata, Vyasa asks Ganesha to assist him in writing the text. Ganesha imposes a precondition that he would do so only if Vyasa would narrate the story without a pause. Vyasa set a counter-condition that Ganesha understand the verses first before transcribing them. Thus Vyasa narrated the entire Mahābhārata and all the Upanishads and the 18 Puranas, while Lord Ganesha wrote.

Vyasa's Jaya (literally, "victory"), the core of the Mahabharata, is a dialogue between Dhritarashtra (the Kuru king and the father of the Kauravas, who opposed the Pāndavas in the Kurukshetra War) and Sanjaya, his adviser and charioteer. Sanjaya narrates the particulars of the Kurukshetra War, fought in eighteen days, chronologically. Dhritarashtra at times asks questions and expresses doubts, sometimes lamenting, fearing the destruction the war would bring on his family, friends and kin.

Sanjaya, in the beginning, gives a description of the various continents of the Earth and numerous planets, and focuses on the Indian subcontinent. Large and elaborate lists are given, describing hundreds of kingdoms, tribes, provinces, cities, towns, villages, rivers, mountains, forests, etc. of the (ancient) Indian subcontinent (Bhārata Varsha). Additionally, he gives descriptions of the military formations adopted by each side on each day, the death of individual heroes and the details of the war-races. Eighteen chapters of Vyasa's Jaya constitute the Bhagavad Gita, a sacred text in Hinduism. Thus, the Jaya deals with diverse subjects, such as geography, history, warfare, religion and morality.

The final version of Vyasa's work is the Mahābhārata. It is structured as a narration by Ugrasrava Sauti, a professional storyteller, to an assembly of rishis who, in the forest of Naimisha, had just attended the 12 year sacrifice known as Saunaka, also known as Kulapati.

Other texts attributed

Puranas

Vyasa is also credited with the writing of the eighteen major Purāṇas, which are works of Indian literature that cover an encyclopedic range of topics covering various scriptures. His son Shuka is the narrator of the major Shrimad Bhagvat purana to Arjuna's grandson Parikshit

Yoga Bhashya

The Yoga Bhashya, a commentary on the Yoga Sutras of Patanjali, is attributed to Vyasa.[11]

Brahma Sutras

The Brahma Sutras are attributed to Badarayana — which makes him the proponent of the crest-jewel school of Hindu philosophy, i.e., Vedanta. Vaishnava Acharyas acknowledge that Badarayana is indeed Vyasa and he is known as Badarayana as he had his ashram in Badari kshetram. Others believe the name to be because the island on which Vyasa was born is said to have been covered with badara (Indian jujube/Ber/Ziziphus mauritiana) trees.[12] Some modern historians, though, suggest that these were two different personalities.

There may have been more than one Vyasa, or the name Vyasa may have been used at times to give credibility to a number of ancient texts.[13] Much ancient Indian literature was a result of long oral tradition with wide cultural significance rather than the result of a single author. However, Vyasa is credited with documenting, compiling, categorizing and writing commentaries on much of this literature.

In Sikhism

In Brahm Avtar, one of the compositions in Dasam Granth, the Second Scripture of Sikhs, Guru Gobind Singh mentions Rishi Vyas as an avatar of Brahma.[14] He is considered the fifth incarnation of Brahma. Guru Gobind Singh wrote brief account of Rishi Vyas's compositions about great kings— Manu, Prithu, Bharath, Jujat, Ben, Mandata, Dilip, Raghu Raj and Aj[14][15]— and attributed to him the store of Vedic learning.[16]

Legacy

Vyasa is widely revered in Hindu traditions. A grand temple in honour of Sri Veda Vyasa has been built at his birthplace in Kalpi, Orai, Uttar Pradesh. The temple is known as Shri Bal Vyas Mandir. Shrimad Sudhindra Teerth Swamiji, the erstwhile spiritual guru of Sri Kashi Math Samsthan, Varanasi, had the vision to construct this temple in 1998. The temple is managed by the Chitrapur Sarasawath Brahmin (CSB) community who belong to the said Sri Kashi Math Samsthan. This beautiful temple has now also become a popular tourist destination.

Notes

- Awakening Indians to India. Chinmaya Mission. 2008. p. 167. ISBN 978-81-7597-434-0.

- What Is Hinduism?: Modern Adventures Into a Profound Global Faith. Himalayan Academy Publications. 2007. p. 230. ISBN 1-934145-00-9.

- "Rishi Ved Vyas – Trikal Darshi Rajender Bhargav". Retrieved 14 September 2019.

- Essays on the Mahābhārata, Arvind Sharma, Motilal Banarsidass Publisher, p. 205

- Kalpriya Nagri, Bundelkhand.

- Strauss, Sarah (2002). "The Master's Narrative: Swami Sivananda and the Transnational Production of Yoga". Journal of Folklore Research. Indiana University Press. 23 (2/3): 221. JSTOR 3814692.

- Skanda Purāṇa, Nāgara Khanda, ch. 147

- Encyclopaedic Dictionary of Puranas, Volume 1 (2001), page 1408

- "Vishnu Purana". Retrieved 15 March 2014.

- Vishnu Purana -Drauni or Asvathama as Next Vyasa Retrieved 2015-03-22

- Ian Whicher. The Integrity of the Yoga Darsana: A Reconsideration of Classical Yoga. SUNY Press. p. 320.

- Gopal, Madan (1990). K.S. Gautam (ed.). India through the ages. Publication Division, Ministry of Information and Broadcasting, Government of India. p. 74.

- The Yoga Sutras of Patanjali. Edwin F. Bryant 2009 page xl

- Dasam Granth, Dr. SS Kapoor

- Line 8, Brahma Avtar, Dasam Granth

- Line 107, Vyas Avtar, Dasam Granth

References

- The Mahabharata of Krishna-Dwaipayana Vyasa, translated by Kisari Mohan Ganguli, published between 1883 and 1896

- The Arthashastra, translated by Shamasastry, 1915

- The Vishnu-Purana, translated by H. H. Wilson, 1840

- The Bhagavata-Purana, translated by A. C. Bhaktivedanta Swami Prabhupada, 1988 copyright Bhaktivedanta Book Trust

- The Jataka or Stories of the Buddha's Former Births, edited by E. B. Cowell, 1895

External links

- The Mahābhārata – Ganguli translation, full text at sacred-texts.com