Valéry Giscard d'Estaing

Valéry Marie René Georges Giscard d'Estaing (UK: /ˌʒiːskɑːr dɛˈstæ̃/,[1] US: /ʒɪˌskɑːr -/,[2][3] French: [valeʁi ʒiskaʁ dɛstɛ̃] (![]()

Valéry Giscard d'Estaing | |

|---|---|

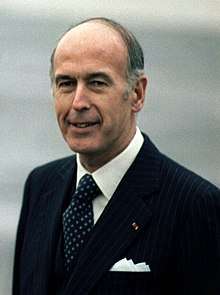

Valéry Giscard d'Estaing in 1978 | |

| President of France | |

| In office 27 May 1974 – 21 May 1981 | |

| Prime Minister | Jacques Chirac Raymond Barre |

| Preceded by | Georges Pompidou |

| Succeeded by | François Mitterrand |

| President of the Regional Council of Auvergne | |

| In office 21 March 1986 – 2 April 2004 | |

| Preceded by | Maurice Pourchon |

| Succeeded by | Pierre-Joël Bonté |

| Minister of the Economy and Finance | |

| In office 20 June 1969 – 27 May 1974 | |

| Prime Minister | Jacques Chaban-Delmas Pierre Messmer |

| Preceded by | François-Xavier Ortoli |

| Succeeded by | Jean-Pierre Fourcade |

| In office 18 January 1962 – 8 January 1966 | |

| Prime Minister | Michel Debré Georges Pompidou |

| Preceded by | Wilfrid Baumgartner |

| Succeeded by | Michel Debré |

| Mayor of Chamalières | |

| In office 15 September 1967 – 19 May 1974 | |

| Preceded by | Pierre Chatrousse |

| Succeeded by | Claude Wolff |

| Personal details | |

| Born | Valéry Marie René Georges Giscard d'Estaing 2 February 1926 Koblenz, French-occupied Germany |

| Political party | CNIP (1956–1962) FNRI (1966–1977) PR (1977–1995) UDF (1978–2002) PPDF (1995–1997) DL (1997–1998) UMP (2002–2004) |

| Spouse(s) | |

| Children | 4, including Henri and Louis |

| Alma mater | École Polytechnique École nationale d'administration |

| Signature |  |

| Military career | |

| Allegiance | |

| Service/ | |

| Years of service | 1944–1945 |

| Rank | Brigadier-chef |

| Battles/wars | Second World War |

| Awards | Croix de guerre |

As Minister of Finance under prime ministers Jacques Chaban-Delmas and Pierre Messmer, he won the presidential election of 1974 with 50.8% of the vote against François Mitterrand of the Socialist Party. His tenure was marked by a more liberal attitude on social issues—such as divorce, contraception and abortion—and attempts to modernise the country and the office of the presidency, notably launching such far-reaching infrastructure projects as the TGV and the turn towards reliance on nuclear power as France's main energy source. However, his popularity suffered from the economic downturn that followed the 1973 energy crisis, marking the end of the "thirty glorious years" after World War II. Giscard d'Estaing faced political opposition from both sides of the spectrum: from the newly unified left of François Mitterrand and a rising Jacques Chirac, who resurrected Gaullism on a right-wing opposition line. In 1981, despite a high approval rating, he missed out on reelection in a runoff against Mitterrand, with 48.2% of the vote.

As a former President of France, Giscard d'Estaing is a member of the Constitutional Council. He also served as President of the Regional Council of Auvergne from 1986 to 2004. Involved with the European Union, he notably presided over the Convention on the Future of Europe that drafted the ill-fated Treaty establishing a Constitution for Europe. In 2003, he was elected to the Académie française, taking the seat that his friend and former President of Senegal Léopold Sédar Senghor had held. At age 94, Giscard is the longest-lived French President in history.

Education

Valéry Marie René Giscard d'Estaing was born on 2 February 1926 in Koblenz, Germany, during the French occupation of the Rhineland.[4] He is the elder son of Jean Edmond Lucien Giscard d'Estaing (29 March 1894 – 3 August 1982), a high-ranking civil servant, and his wife, Marthe Clémence Jacqueline Marie (May) Bardoux (6 May 1901 – 13 March 2003).

His mother was a daughter of senator and academic Achille Octave Marie Jacques Bardoux, making her a great-granddaughter of minister of state education Agénor Bardoux. She was also, through her own mother, a granddaughter of historian Georges Picot, a niece of diplomat François Georges-Picot, and a great-great-great-granddaughter of King Louis XV of France by one of his mistresses, Catherine Eléonore Bernard (1740–1769), through her great-grandfather Marthe Camille Bachasson, Count of Montalivet, by whom Giscard d'Estaing is a multiple descendant of Charlemagne.

Giscard had an older sister, Sylvie (1924–2008). He has a younger brother, Olivier (born 1927), as well as two younger sisters: Isabelle (born 1935) and Marie-Laure (born 1939). Despite the addition of "d'Estaing" to the family name by his grandfather, Giscard is not descended from the extinct noble family of Vice-Admiral d'Estaing, that name being adopted by his grandfather in 1922 by reason of a distant connection to another branch of that family,[5] from which they were descended with two breaks in the male line from an illegitimate line of the Viscounts d'Estaing.

He joined the French Resistance and participated in the Liberation of Paris; during the liberation he was tasked with protecting Alexandre Parodi. He then joined the French First Army and served until the end of the war. He was later awarded the Croix de guerre for his military service.

In 1948, he spent a year in Montreal, Canada, where he worked as a teacher at Collège Stanislas.[6]

He studied at Lycée Blaise-Pascal in Clermont-Ferrand, École Gerson and Lycées Janson-de-Sailly and Louis-le-Grand in Paris. He graduated from the École polytechnique and the École nationale d'administration (1949–1951) and chose to enter the prestigious Inspection des finances. He acceded to the Tax and Revenue Service, then joined the staff of Prime Minister Edgar Faure (1955–1956). He is fluent in German.[7]

Early political career

First offices: 1956–1962

In 1956, he was elected to Parliament as a deputy for the Puy-de-Dôme département, in the domain of his maternal family. He joined the National Centre of Independents and Peasants (CNIP), a conservative grouping. After the proclamation of the Fifth Republic, the CNIP leader Antoine Pinay became Minister of Economy and Finance and chose him as Secretary of State for Finances from 1959 to 1962.

Member of the Gaullist majority: 1962–1974

In 1962, while Giscard had been nominated Minister of Economy and Finance, his party broke with the Gaullists and left the majority coalition. The CNIP reproached President Charles de Gaulle for his euroscepticism. But Giscard refused to resign and founded the Independent Republicans (RI), which became the junior partner of the Gaullists in the "presidential majority".

However, in 1966, he was dismissed from the cabinet. He transformed the RI into a political party, the National Federation of the Independent Republicans (FNRI), and founded the Perspectives and Realities Clubs. He did not leave the majority, but became more critical. In this, he criticised the "solitary practice of the power" and summarised his position towards De Gaulle's policy by a "yes, but ...". As chairman of the National Assembly Committee on Finances, he harassed his successor in the cabinet.

For that reason the Gaullists refused to re-elect him to that position after the 1968 legislative election. In 1969, unlike most of FNRI's elected officials, Giscard advocated a "no" vote in the constitutional referendum concerning the regions and the Senate, while De Gaulle had announced his intention to resign if the "no" won. The Gaullists accused him of being largely responsible for De Gaulle's departure.

During the 1969 presidential campaign he supported the winning candidate Georges Pompidou, after which he returned to the Ministry of Economy and Finance. On the French political scene, he appeared as a young brilliant politician, and a preeminent expert in economic issues. He was representative of a new generation of politicians emerging from the senior civil service, seen as "technocrats".

Presidential election victory

In 1974, after the sudden death of President Georges Pompidou, Giscard announced his candidacy for the presidency. His two main challengers were François Mitterrand for the left and Jacques Chaban-Delmas, a former Gaullist Prime Minister. Supported by his FNRI party, he obtained the rallying of the centrist Reforming Movement. Moreover, he benefited from the divisions in the Gaullist party. Jacques Chirac and other Gaullist personalities published the "Call of the 43" where they explained that Giscard was the best candidate to prevent the election of Mitterrand. In the election, Giscard finished well ahead of Chaban-Delmas in the first round, though coming second to Mitterrand. In the run-off on 20 May, however, Giscard narrowly defeated Mitterrand, receiving 50.7% of the vote.[8]

President of France

Domestic policy

Giscard was finally elected President of France, defeating Socialist candidate François Mitterrand by 425,000 votes—still the closest election in French history. At 48, he was the third youngest president in French history at the time, after Louis-Napoléon Bonaparte and Jean Casimir-Perier. He promised "change in continuity". He made clear his desire to introduce various reforms and modernise French society, which was an important part of his presidency. He for instance reduced from 21 to 18 the age of majority and pushed for the development of the TGV high speed train network and the Minitel, a precursor of the Internet.[9] He promoted nuclear power, as a way to assert French independence. In 1975 he invited the heads of government from West Germany, Italy, Japan, the United Kingdom and the United States to a summit in Rambouillet, to form the Group of Six major economic powers (now the G7, including Canada). Economically, Giscard's presidency saw a steady rise in personal incomes, with the buying power of workers going up by 29% and old age pensioners by 65%.[10]

Giscard billed himself as "a conservative who likes change," and initially tried to project a less monarchical image than had been the case for past French presidents. He wore an ordinary business suit to his inauguration and eschewed the traditional motorcade down the Champs-Elysées in favour of strolling down the street. He took a ride on the Métro, ate monthly dinners with ordinary Frenchmen, and even invited garbage men from Paris to have breakfast with him in the Élysée Palace. However, when he learned that most Frenchmen were somewhat cool to this display of informality, Giscard became so aloof and distant that his opponents frequently attacked him as being too far removed from ordinary citizens.[11]

In home policy, the president's reforms worried the conservative electorate and the Gaullist party, especially the law by Simone Veil legalising abortion. Although he said he had "deep aversion against capital punishment", Giscard claimed in his 1974 campaign that he would apply the death penalty to people committing the most heinous crimes.[12] He did not commute three of the death sentences that he had to decide upon during his presidency (although he did so in several other occasions), keeping France as the last country in the European Community to apply the death penalty. These executions would be the last ever in France and, had executions not resumed in the United States, the last in the Western world, as was the case until 1979 when John Spenkelink was executed by Florida. Death sentences were continually handed out in France for the remaining four years of Giscard's term but were all commuted in 1981, when capital punishment was abolished.

A rivalry arose with his Prime Minister Jacques Chirac, who resigned in 1976. Raymond Barre, called the "best economist in France" at the time, succeeded him. He led a policy of strictness in a context of economic crisis ("Plan Barre").

Unexpectedly, the right-wing coalition won the 1978 legislative election. Nevertheless, relations with Chirac, who had founded the Rally for the Republic (RPR), became more tense. Giscard reacted by founding a centre-right confederation, the Union for French Democracy (UDF).

Foreign policy

In 1975 Giscard pressured the future King of Spain Juan Carlos I to leave Chilean dictator Augusto Pinochet out of his coronation by stating that if Pinochet attended he would not. Having been told by Juan Carlos I not to attend the coronation, Pinochet left Spain having only attended the funeral of Francisco Franco during his visit.[13] Although France received many Chilean political refugees, Valéry Giscard d'Estaing's government secretly collaborated with Pinochet's and Videla's junta as shown by journalist Marie-Monique Robin.[14]

Africa

Giscard continued de Gaulle's African policy. It was supported with French military units, and a large naval presence in the Indian Ocean. Over 260,000 Frenchmen worked in Africa, focused especially on delivering oil supplies. There was some effort to build up oil refineries and aluminum smelters, but little effort to develop small-scale local industry, which the French wanted to monopolize for the mainland. Senegal, Ivory Coast, Gabon, and Cameroon were the largest and most reliable African allies, and received most of the investments.[15] In 1977, in the Opération Lamantin, he ordered fighter jets to deploy in Mauritania and suppress the Polisario guerrillas fighting against Mauritania, However the French-installed Mauritanian leader Moktar Ould Daddah was overthrown by his own army some time later, and a peace agreement was signed with the Sahrawi movement.

Most controversial was his involvement with the regime of Jean-Bédel Bokassa in the Central African Republic. Giscard was initially a friend of Bokassa, and supplied the regime. However, the growing unpopularity of that government led Giscard to begin distancing himself from Bokassa. In 1979, French troops helped drive Bokassa out of power and restore former president David Dacko.[16] This action was also controversial, particularly since Dacko was Bokassa's cousin and had appointed Bokassa as head of the military, and unrest continued in the Central African Republic leading to Dacko being overthrown in another coup in 1981.

1981 presidential election

In the 1981 presidential election, Giscard took a severe blow to his support when Chirac ran against him in the first round. Chirac finished third and refused to recommend that his supporters back Giscard in the runoff, though he declared that he himself would vote for Giscard. Giscard lost to Mitterrand by 3 points in the runoff,[17] and since then has blamed Chirac for his defeat.[18] To this day, it is widely said that Giscard loathes Chirac. Certainly on many occasions Giscard has criticised Chirac's policies despite supporting Chirac's governing coalition.

Post-presidency

Return to politics: 1984–2004

After his defeat, Giscard retired temporarily from politics. In 1984, he regained his seat in Parliament and won the presidency of the regional council of Auvergne. In this position, he tried to encourage tourism to the région, founding the "European Centre of Volcanology" and theme park Vulcania. He was President of the Council of European Municipalities and Regions from 1997 to 2004.

In 1982, along with his friend Gerald Ford, he co-founded the annual AEI World Forum. He took part, with a prominent role, in the annual Bilderberg private conference. He has also served on the Trilateral Commission after being president, writing papers with Henry Kissinger.

He hoped to become Prime Minister of France during the first "cohabitation" (1986–88) or after the re-election of Mitterrand with the theme of "France united", but he was not chosen for this position. During the 1988 presidential campaign, he refused to choose publicly between the two right-wing candidates, his two former Prime Ministers Jacques Chirac and Raymond Barre. This attitude was interpreted as indicating that he wanted to regain the UDF leadership.

Indeed, he served as President of the UDF from 1988 to 1996, but he was faced with the rise of a new generation of politicians called the "renovationmen". Most of the UDF politicians supported the candidacy of the RPR Prime Minister Édouard Balladur at the 1995 presidential election, but Giscard supported his old rival Jacques Chirac, who won the election. That same year Giscard suffered a setback when he lost a close election for the mayoralty of Clermont-Ferrand.[19]

In 2000, he made a parliamentary proposal to reduce the length of a presidential term from 7 to 5 years. President Chirac held a referendum on this issue, and the "yes" side won. He did not run for a new parliamentary term in 2002. His son Louis Giscard d'Estaing was elected in his constituency.

Retired from politics: 2004–present

In 2003, Valéry Giscard d'Estaing was admitted to the Académie française.[20]

Following his narrow defeat in the regional elections of March 2004, marked by the victory of the left wing in 21 of 22 regions, he decided to leave partisan politics and to take his seat on the Constitutional Council as a former president of the Republic.[21] Some of his actions there, such as his campaign in favour of the Treaty establishing the European Constitution, were criticised as unbecoming to a member of this council, which should embody nonpartisanship and should not appear to favour one political option over the other. Indeed, the question of the membership of former presidents in the Council was raised at this point, with some suggesting that it should be replaced by a life membership in the Senate.[22][23]

Since then, Giscard has occasionally expressed opinions about current affairs. On 19 April 2007, he endorsed Nicolas Sarkozy for the presidential election. He has supported the creation of the centrist Union of Democrats and Independents in 2012 and the introduction of same-sex marriage in France in 2013. In 2016, he supported former Prime minister François Fillon in The Republicans presidential primaries.

A 2014 poll suggested that 64% of the French thought he had been a good president. He is considered to be an honest and competent politician, but also to be a distant man.[24]

On 21 January 2017, with a lifespan of 33,226 days, he surpassed Émile Loubet (1838–1929) in terms of longevity, and is now the oldest former president in French history.

European activities

Giscard has, throughout his political career, always been a proponent of greater European union. In 1978, he was for this reason the obvious target of Jacques Chirac's Call of Cochin, denouncing the "party of the foreigners".[25]

From 1989 to 1993, Giscard served as a member of the European Parliament. From 1989 to 1991, he was also chairman of the Liberal and Democratic Reformist Group.[26]

From 2001 to 2004 he served as President of the Convention on the Future of Europe. On 29 October 2004, the European heads of state, gathered in Rome, approved and signed the European Constitution based on a draft strongly influenced by Giscard's work at the Convention.[27]

Although the Constitution was rejected by French voters in May 2005, Giscard continued to actively lobby for its passage in other European Union states. Giscard d'Estaing attracted international attention at the time of the June 2008 Irish vote on the Lisbon Treaty. In an article for Le Monde[28] in June 2007, he said that "public opinion will be led to adopt, without knowing it, the proposals we dare not present to them directly". Although the quote is accurate, it was part of a critique, taken out of context, of a suggestion made by some unnamed persons. In the next paragraph Giscard goes on to reject the idea of this course of action by saying, "This approach of 'divide and ratify' is clearly unacceptable. Perhaps it is a good exercise in presentation. But it would confirm to European citizens the notion that European construction is a procedure organised behind their backs by lawyers and diplomats." In the following paragraphs he goes on to appeal for an "honest treaty" and "total transparency" to allow citizens to hear the debate for themselves.

Since 2008 he has been the Honorary President of the Permanent Platform of Atomium Culture, an innovative structure composed of some of the most authoritative universities, newspapers and businesses in Europe for the selection, exchange and dissemination of the most innovative European research, to increase the movement of knowledge across borders, across sectors and to the public at large.[29] On 27 November 2009, Giscard publicly launched the Permanent Platform of Atomium Culture during its first conference, held at the European Parliament,[30] declaring: "European intelligence could be at the very root of the identity of the European people."[31] A few days before he had signed, together with the President of Atomium Culture Michelangelo Baracchi Bonvicini, the European Manifesto of Atomium Culture.

Political career

President of the French Republic: 1974–1981.

Member of the Constitutional Council of France: Since 1981.

Governmental functions

Secretary of State for Finances: 1959–1962.

Minister of Finances and Economic Affairs: 1962–1966.

Minister of Economy and Finances: 1969–1974.

Minister of State, minister of Economy and Finances: March–May 1974 (Resignation, became President of the French Republic in 1974)

Electoral mandates

European Parliament

Member of European Parliament: 1989–1993 (Reelected member of the National Assembly of France in 1993).

National Assembly of France

Member of the National Assembly of France for Puy-de-Dôme: 1956–1959 (Became minister in 1959) / Reelected in 1962, but he stays minister / 1967–1969 (Became minister in 1969) / Reelected in 1973, but he stays minister / 1984–1989 (Became member of European Parliament in 1989) / 1993–2002. Elected in 1956, re-elected in 1958, 1962, 1967, 1968, 1973.

Regional Council

President of the Regional Council of Auvergne: 1986–2004. Reelected in 1992, 1998.

Regional councillor of Auvergne: 1986–2004. Reelected in 1992, 1998.

General Council

General councillor of Puy-de-Dôme: 1958–1974 (Resignation, became President of the French Republic in 1974) / 1982–1988 (Resignation). Reelected in 1964, 1970, 1982.

Municipal Council

Mayor of Chamalières: 1967–1974 (Resignation, Became President of the French Republic in 1974). Reelected in 1971.

Municipal councillor of Chamalières: 1967–1977. Reelected in 1971.

Political functions

President of the National Federation of the Independent Republicans (Independent Republicans): 1966–1974 (Became President of the French Republic in 1974).

President of the Union for French Democracy: 1988–1996.

Personal life

Giscard's name is often shortened to "VGE" by the French media. A less flattering nickname is l'Ex (the Ex), used mostly by the weekly satirical newspaper Le Canard enchaîné.

Family

On 17 December 1952, Giscard married his cousin Anne-Aymone Sauvage de Brantes, a daughter of Count François Sauvage de Brantes, who had died in a concentration camp in 1944, and his wife, the former Princess Aymone de Faucigny-Lucinge. Their children are: Valérie-Anne Marie Aymone (1953 –), Henri Marie Edmond Valéry, Louis Joachim Marie François and Jacinte Marguerite Marie (1960 – 2018). Louis was a French conservative Representative; Henri is the president of the tourism company Club Méditerranée.

Giscard's private life was the source of many rumours at both national and international level. His family did not live in the presidential Élysée Palace, and The Independent reported on his affairs with women.[32] In 1974, Le Monde reported that he used to leave a sealed letter stating his whereabouts in case of emergency.[33]

He is an uncle of artist Aurore Giscard d'Estaing, who was formerly married to American actor Timothy Hutton.

Possession of the Estaing castle

In 2005 he and his brother bought the castle of Estaing, a famous place in the French district of Aveyron and formerly a possession of the above-mentioned admiral d'Estaing who was beheaded in 1794. The castle is not used as a residence but it has symbolic value. The two brothers explained that the purchase, supported by the local municipality, was an act of patronage. However, a number of major newspapers in several countries questioned their motives and some hinted at self-appointed nobility and a usurped historical identity.[34]

Questions about his 2009 novel

Giscard wrote his second romantic novel, published on 1 October 2009 in France, entitled The Princess and The President. It tells the story of a French head of state having a romantic liaison with a character called Patricia, Princess of Cardiff. This fuelled rumours that the piece of fiction was based on a real-life liaison between Giscard and Diana, Princess of Wales.[35] He later stressed that the story was entirely made up and no such affair had happened.[36]

Honours

National honours

- Grand-croix (and former Grand Master) of the Legion of Honour[37]

- Grand-croix (and former Grand Master) of the Ordre National du Mérite[37]

- Croix de guerre 1939–1945[37]

European honours

In 2003 he received the Charlemagne Award of the German city of Aachen. He is also a Knight of Malta.

He travels the world giving speeches on the European Union. During a visit to Ireland, d'Estaing was made an Honorary Patron of the University Philosophical Society, Trinity College, Dublin.

Foreign honours

As Minister of Finance

As President of France

Other honours

.svg.png)

.svg.png)

Heraldry

.svg.png)

President Giscard d'Estaing was granted a coat of arms by Queen Margrethe II of Denmark upon his appointment to the Order of the Elephant. He was also granted a coat of arms by King Carl XVI Gustav of Sweden (Photo), for his induction as a Knight of the Seraphim.[45]

References

- "Giscard d'Estaing, Valéry". Lexico UK Dictionary. Oxford University Press. Retrieved 30 June 2019.

- "Giscard d'Estaing". The American Heritage Dictionary of the English Language (5th ed.). Boston: Houghton Mifflin Harcourt. Retrieved 30 June 2019.

- "Giscard d'Estaing". Merriam-Webster Dictionary. Retrieved 30 June 2019.

- Profile of Valéry Giscard d'Estaing

- See French Wikipedia

- Mon tour de jardin, Robert Prévost, p. 96, Septentrion 2002

- "Valéry Giscard d'Estaing: "In Wahrheit ist die Bedrohung heute nicht so groß wie damals"". Frankfurter Allgemeine Zeitung. 15 November 2016. Retrieved 20 November 2016.

- Lewis, Flora (20 May 1974). "France Elects Giscard President For 7 Years After A Close Contest; Left Turned Back". The New York Times. Archived from the original on 27 February 2014.

- "History of the Minitel". Whitepages.fr. Retrieved 20 November 2016.

- D. L. Hanley, Miss A P Kerr, N. H. Waites (17 August 2005). Contemporary France: Politics and Society Since 1945. ISBN 9781134974238. Retrieved 20 November 2016 – via Google Books.CS1 maint: uses authors parameter (link)

- Thompson, Wayne C. (2013). The World Today 2013: Western Europe. Lanham, Maryland: Stryker-Post Publications. ISBN 978-1-4758-0505-5.

- "Ocala Star-Banner – Google News Archive Search".

- Cedéo Alvarado, Ernesto (4 February 2008). "Rey Juan Carlos abochornó a Pinochet". Panamá América. Retrieved 4 April 2016.

- Conclusion of Marie-Monique Robin's Escadrons de la mort, l'école française (in French)/ Watch here film documentary (French, English, Spanish)

- John R. Frears, France in the Giscard Presidency (1981) pp 109-127.

- Bradshaw, Richard; Fandos-Rius, Juan (27 May 2016). Historical Dictionary of the Central African Republic. Rowman & Littlefield. ISBN 9780810879928.

- "Valery Giscard d'Estaing | president of France". Encyclopædia Britannica. Retrieved 10 November 2017.

- Eder, Richard; Times, Special to the New York (11 May 1981). "MITTERRAND BEATS GISCARD; SOCIALIST VICTORY REVERSES TREND OF 23 YEARS IN FRANCE". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved 10 November 2017.

- "L'UMP tente un nouvel assaut en Auvergne". Le Figaro. 7 February 2008. Retrieved 20 November 2016.

- "VGE devient Immortel". Le Nouvel Observateur. 17 December 2003. Retrieved 20 November 2016.

- VGE page on Oxford Reference.

- "La Chiraquie veut protéger son chef quand il quittera l'Elysée", Libération, 14 January 2005

- See also the constitutional amendment proposals by senator Patrice Gélard

- "Fichier BVA pour Le Parisien" (PDF). Retrieved 20 November 2016.

- "Le "parti de l'étranger" et "le bruit et l'odeur", les précédents dérapages de Jacques Chirac". 20 Minutes. 24 November 2009. Retrieved 20 November 2016.

- "List of all current and former Members". European Parliament. Retrieved 20 November 2016.

- Sabine Verhest (17 June 2003). "Valéry Giscard d'Estaing l'Européen". La Libre.be. Retrieved 20 November 2016.

- ""Le Traité simplifié, oui, mutilé, non", par Valéry Giscard d'Estaing". Le Monde. Retrieved 20 November 2016.

- "The Honorary President of Atomium Culture Valéry Giscard d'Estaing speaks at the public launch and first conference, Atomium Culture". Atomiumculture.eu. Retrieved 3 June 2011.

- Von Joachim Müller-Jung (27 November 2009). "Atomium Culture: Bienenstock der Intelligenz – Atomium Culture – Wissen". Frankfurter Allgemeine Zeitung. Retrieved 3 June 2011.

- Lichfield, John (3 February 1998). "French get peek at all the presidents' women". The Independent. Retrieved 17 January 2014.

- "Hemeroteca La Vanguardia, November 30th 1974 (Spanish)".

- Le Monde 24 December 04, AFP Toulouse 23 December 04, Le Figaro 22 January 05, Neue Zürcher Zeitung 15 February 05, The Sunday Times 16 January 05

- "Giscard hints at affair with Diana". Connexion. 21 September 2009. Archived from the original on 5 October 2009. Retrieved 3 June 2011.

- "Giscard: I made up Diana love story". Connexion. 24 September 2009. Archived from the original on 5 October 2009. Retrieved 3 June 2011.

- Académie française, Valéry GISCARD d’ESTAING

- Italian Presidency Website, GISCARD D'ESTAING S.E. Valery, "Cavaliere di Gran Croce Ordine al Merito della Repubblica Italiana", when Minister of Economy and Finance

- "Viagem do PR Geisel à França" (PDF). Retrieved 19 January 2019.

- borger.dk, Ordensdetaljer, Valéry Giscard d'Estaing Archived 17 December 2012 at Archive.today, Hans Excellence, fhv. præsident for Republikken Frankrig

- Coat of arms in the chapel of Frederiksborg Castle

- Portuguese Presidency Website, Orders search form : type "ESTAING Valéry Giscard" in "nome", then click "Pesquisar"

- Spanish Official Gazette

- Spanish Official Gazette

- Heraldry Archived 12 November 2013 at the Wayback Machine of the Order of the Seraphim

Further reading

- Bell, David. Presidential Power in Fifth Republic France (2000) pp 127–48.

- Frears, J. R. France in the Giscard Presidency (1981) 224p. covers 1974 to 1981

- Ryan, W. Francis. "France under Giscard" Current History (May 1981) 80#466, pp 201–6.

- Wilsford, David, ed. Political leaders of contemporary Western Europe: a biographical dictionary (Greenwood, 1995) pp 170–176.

External links

| Wikiquote has quotations related to: Valéry Giscard d'Estaing |

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Valéry Giscard d'Estaing. |

- (in French) Biography on the French National Assembly website

- (in French) First and second-round results of French presidential elections

| National Assembly of France | ||

|---|---|---|

| Proportional representation | Member for Puy-de-Dôme 1956–1958 |

Constituency abolished |

| New constituency | Member for Puy-de-Dôme 1986–1988 | |

| Preceded by New constituency (1958) Guy Fric (1962, 1967) Jean Morellon (1973) Claude Wolff (1984) |

Member for Puy-de-Dôme's 2nd constituency 1958–1959 1962–1963 1967–1969 1973 1984–1986 |

Succeeded by Guy Fric (1959, 1963) Jean Morellon (1969, 1973) Constituency abolished (1986) |

| New constituency | Member for Puy-de-Dôme's 3rd constituency 1988–1989 |

Succeeded by Claude Wolff |

| Preceded by Claude Wolff |

Member for Puy-de-Dôme's 3rd constituency 1993–2002 |

Succeeded by Louis Giscard d'Estaing |

| European Parliament | ||

| Proportional representation | Member of the European Parliament for France 1989–1993 |

Proportional representation |

| Political offices | ||

| New office | Secretary of State for Finance 1959–1962 |

Succeeded by Max Fléchet |

| Preceded by Pierre Chatrousse |

Mayor of Chamalières 1967–1974 |

Succeeded by Claude Wolff |

| Preceded by Wilfrid Baumgartner |

Minister of Finance and Economics Affairs 1962–1966 |

Succeeded by Michel Debré |

| Preceded by François-Xavier Ortoli |

Minister of Economy and Finance 1969–1974 |

Succeeded by Jean-Pierre Fourcade |

| Preceded by Alain Poher Acting |

President of France 1974–1981 |

Succeeded by François Mitterrand |

| Preceded by Maurice Pourchon |

President of the Regional Council of Auvergne 1986–2004 |

Succeeded by Pierre-Joël Bonté |

| Party political offices | ||

| New political party | President of the Independent Republicans 1966–1974 |

Succeeded by Michel Poniatowski |

| Preceded by Jean Lecanuet |

President of the Union for French Democracy 1988–1996 |

Succeeded by François Léotard |

| Regnal titles | ||

| Preceded by Alain Poher Acting |

Co-Prince of Andorra 1974–1981 With Joan Martí i Alanis |

Succeeded by François Mitterrand |

| Preceded by Joan Martí i Alanis |

Succeeded by Joan Martí i Alanis | |

| Catholic Church titles | ||

| Preceded by Alain Poher Acting |

Honorary Canon of the Archbasilica of St. John Lateran 1974–1981 |

Succeeded by François Mitterrand |

| Diplomatic posts | ||

| New office | Chair of the G6 1975 |

Succeeded by Gerald Ford |

| Academic offices | ||

| Preceded by Aleksander Kwaśniewski |

Invocation Speaker of the College of Europe 2002 |

Succeeded by Joschka Fischer |

| Order of precedence | ||

| Preceded by Richard Ferrand as President of the National Assembly |

French order of precedence as Former President of the Republic |

Succeeded by Nicolas Sarkozy as Former President of the Republic |