John Spenkelink

John Arthur Spenkelink (March 29, 1949 – May 25, 1979) was a convicted American murderer. He was executed in 1979, the first convicted criminal to be executed in Florida after capital punishment was reinstated in 1976, and the second (after Gary Gilmore) in the United States.

John Spenkelink | |

|---|---|

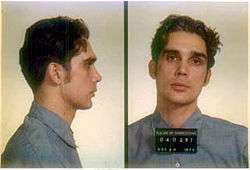

Spenkelink's Florida Department of Corrections mugshot | |

| Born | John Arthur Spenkelink March 29, 1949 |

| Died | May 25, 1979 (aged 30) |

| Cause of death | Executed (electric chair) |

| Resting place | Rose Hills Memorial Park Whittier, California |

| Parent(s) | Lois Spenkelink |

| Criminal charge | Murder |

| Penalty | Death (1976) |

Crime

Spenkelink was a drifter who was convicted in California for armed robbery and had been sentenced to five years-to-life.[1] He had just escaped from the Slack Canyon Conservation Camp when he shot and killed a small-time criminal named Joseph Szymankiewicz in Tallahassee, Florida, in 1973.[1] He claimed that he acted in self-defense—that Szymankiewicz had stolen his money, forced him to play Russian roulette, and sexually assaulted him. However, evidence and witness testimony from a co-defendant indicated that Spenkelink left their shared motel room, returned with a gun, and shot Szymankiewicz in the back.[2] He turned down a plea bargain to second-degree murder that would have resulted in a life sentence. In 1976 he was convicted of first-degree murder and sentenced to death. His co-defendant was acquitted.[2]

Death Penalty

In 1972, the U.S. Supreme Court had banned the death penalty, ruling that it had been applied unfairly. Florida and other states rushed to rewrite less-arbitrary laws.[3]

Spenkelink appealed his sentence, but in 1977, Governor Reubin Askew of Florida signed Spenkelink's first death warrant.[4] In 1979 Askew's successor, Governor Bob Graham, signed a second death warrant. Spenkelink continued to appeal, earning stays from both the U.S Court of Appeals and the U.S. Supreme Court, but both stays were overturned,[5] meaning that Spenkelink would be the first man to suffer the death penalty involuntarily (Gilmore had insisted he wanted to die)[6] since executions were resumed in the U.S. in 1976.

Spenkelink's case became a national cause célèbre, encompassing both the broader debate over the morality of the death penalty and the narrower question of whether the punishment fitted Spenkelink's crime. His cause was taken up by former Florida Governor LeRoy Collins, actor Alan Alda, and singer Joan Baez, among many others.[1] Also at issue was the assertion that capital punishment discriminated against the poor and underprivileged—Spenkelink often signed his prison correspondence with the epigram, "capital punishment means those without capital get the punishment."[7]

The execution was finally carried out on May 25, 1979, in "Old Sparky", the Florida State Prison electric chair.[8] That morning, Doug Tracht, a popular Jacksonville disc jockey, aired a recording of sizzling bacon on his radio program and dedicated it to Spenkelink.[9][10]

Aftermath

Abuse allegations

Shortly after Spenkelink's execution and burial at Rose Hills Memorial Park, another Florida death row inmate alleged that prison officials had manhandled and assaulted Spenkelink during preparation for his execution. Several decisions lent credence to these allegations: corrections officials had obscured the death chamber's viewing window while Spenkelink was strapped to the electric chair, citing anonymity concerns; the county did not perform an autopsy on Spenkelink (in violation of state law) because the county coroner considered it a redundant and prohibitively expensive policy; and the prison superintendent had limited visits from family and clergy on Spenkelink's execution day, citing fear of a suicide attempt.

Governor Graham commissioned an investigation, which in September 1979 concluded that Spenkelink had been "taunted" and had loud exchanges with prison guards and staff immediately before his execution, but had not been physically abused.[11] Florida corrections officials responded by allowing witnesses to see the complete execution process going forward.[1] Florida's counties now perform autopsies on all executed inmates.[12][13]

Murder allegations

In spite of the state's investigation, a rumor began that Spenkelink had been murdered prior to his being brought into the death chamber.[14] The rumor reached Spenkelink's mother Lois, who, after encouragement from a spiritual advisor, paid to have her son's body exhumed for a post-mortem examination.[15] On March 6, 1981, Los Angeles County Coroner Thomas Noguchi announced his finding that the cause of Spenkelink's death was indeed electrocution.[16]

See also

References

- Von Drehle, David. Among the Lowest of the Dead: Inside Death Row. New York: Fawcett Crest (imprint of Ballantine Books), 1996. ISBN 0449225232 pp. 49-51

- Nash, Jay Robert (1992-07-10). World Encyclopedia of 20th Century Murder. Rowman & Littlefield. ISBN 9781590775325.

- "Happy Anniversary, Sparky". NBC 6 South Florida. Retrieved 2018-03-25.

- "John A. SPENKELINK, Applicant, v. Louie L. WAINWRIGHT et al. No. A-1016". LII / Legal Information Institute. Retrieved 2018-03-25.

- Times, Special To the New York (1979-05-25). "2 Courts Lift Stays, Clearing Way For Execution of Florida Murderer". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved 2018-03-25.

- BEECHAM, BILL (1987-01-11). "'Let's Do It'". Los Angeles Times. ISSN 0458-3035. Retrieved 2018-03-25.

- John Spenkelink: ExecutedToday.com archive Retrieved April 28, 2011.

- Curry, Bill (1979-05-26). "Convicted Murderer Executed by Florida". Washington Post. ISSN 0190-8286. Retrieved 2018-03-25.

- Michaud S, Aynesworth H (1999): The Only Living Witness. Penguin Putnam, ISBN 0-451-16372-9, p. 10.

- "Florida Wields Death Law". The Daily Oklahoman. 26 August 1979. Retrieved 5 January 2014.

- "Panel Says Killer Was Taunted Before Execution". The New York Times. 1979-09-23. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved 2018-03-25.

- "Timeline: 1979 - A History of Corrections in Florida". www.dc.state.fl.us. Retrieved 2018-03-25.

- Quigley, Christine (2013-09-13). The Corpse: A History. McFarland. ISBN 9781476613772.

- AP. "AROUND THE NATION; Body of Executed Murderer Is Exhumed in California". Retrieved 2018-03-25.

- "The results of an autopsy on the exhumed body..." UPI. Retrieved 2018-03-25.

- "Detroit Free Press from Detroit, Michigan on March 6, 1981 · Page 18". Newspapers.com. Retrieved 2018-03-25.

External links

- Long article on Spenkelink - TIME Magazine [as of 2015, behind paywall]

- Article on Spenkelink and others - St. Petersburg Times

- John Spenkelink at Find a Grave

| Preceded by Gary Gilmore |

People executed in US | Succeeded by Jesse Bishop |