Northumbrian Old English

Northumbrian (Old English: Norðanhymbrisċ) was a dialect of Old English spoken in the Anglian Kingdom of Northumbria. Together with Mercian, Kentish and West Saxon, it forms one of the sub-categories of Old English devised and employed by modern scholars.

| Part of a series on |

| Old English |

|---|

|

Dialects

|

|

History |

The dialect was spoken from the Humber, now within England, to the Firth of Forth, now within Scotland. During the Viking invasions of the 9th century, Northumbrian came under the influence of the languages of the Viking invaders.

The earliest surviving Old English texts were written in Northumbrian: these are Caedmon's Hymn (7th century) and Bede's Death Song (8th century). Other works, including the bulk of Caedmon's poetry, have been lost. Other examples of this dialect are the Runes on the Ruthwell Cross from the Dream of the Rood. Also in Northumbrian are the 9th-century Leiden Riddle[1] and the mid-10th-century gloss of the Lindisfarne Gospels.

The Viking invasion forced a division of the dialect into two distinct subdialects. South of the River Tees, the southern Northumbrian version was heavily influenced by Norse, while northern Northumbrian retained many Old English words lost to the southern subdialect and influenced the development of English in northern England, especially the dialects of modern North East England and Scotland. In addition, Scots (including Ulster Scots) is descended from the Northumbrian dialect,[2] as is modern Northumbrian and other dialects of Northern English.

The Lord's Prayer

Some Scottish and Northumbrian folk still say /uːr ˈfeðər/ or /uːr ˈfɪðər/ "our father" and [ðuː eːrt] "thou art".[3] The Lord's Prayer as rendered below dates from c. 650.[4]

FADER USÆR ðu arð in heofnu

Sie gehalgad NOMA ÐIN.

Tocymeð RÍC ÐIN.

Sie WILLO ÐIN

suæ is in heofne and in eorðo.

HLAF USERNE of'wistlic sel ús todæg,

and f'gef us SCYLDA USRA,

suæ uoe f'gefon SCYLDGUM USUM.

And ne inlæd usih in costunge,

ah gefrig usich from yfle. [5]

Bede's Death Song

Fore thaem neidfaerae ‖ naenig uuiurthit

thoncsnotturra, ‖ than him tharf sie

to ymbhycggannae ‖ aer his hiniongae

huaet his gastae ‖ godaes aeththa yflaes

aefter deothdaege ‖ doemid uueorthae.[6]

Cædmon's Hymn

Nū scylun hergan ‖ hefaenrīcaes Uard,

metudæs maecti ‖ end his mōdgidanc,

uerc Uuldurfadur, ‖ suē hē uundra gihwaes,

ēci dryctin ‖ ōr āstelidæ

hē ǣrist scōp ‖ aelda barnum

heben til hrōfe, ‖ hāleg scepen.

Thā middungeard ‖ moncynnæs Uard,

eci Dryctin, ‖ æfter tīadæ

firum foldu, ‖ Frēa allmectig.<ref> Marsden, Richard (2004), Old English Reader, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, p. 80, collated with manuscript facsimile.</ref>

The Leiden Riddle

Mec se uēta uong, uundrum frēorig,

ob his innaðae <span style="text-decoration:overline;">ae</span>rest cændæ.

Ni u<span style="text-decoration:overline;">aa</span>t ic mec biuorthæ uullan fl<span style="text-decoration:overline;">iu</span>sum,

hērum ðerh hēhcraeft, hygiðonc....

Uundnae mē ni bīað ueflæ, ni ic uarp hafæ,

ni ðerih ðreatun giðraec ðrēt mē hlimmith,

ne mē hrūtendu hrīsil scelfath,

ni mec ōuana <span style="text-decoration:overline;">aa</span>m sceal cnyssa.

Uyrmas mec ni āuēfun uyrdi craeftum,

ðā ði geolu gōdueb geatum fraetuath.

Uil mec huethrae su<span style="text-decoration:overline;">ae</span> ðēh uīdæ ofaer eorðu

hātan mith hæliðum hyhtlic giuǣde;

ni an<span style="text-decoration:overline;">oe</span>gun ic mē <span style="text-decoration:overline;">ae</span>rigfaerae egsan brōgum,

ðēh ði n... ...n sīæ nīudlicae ob cocrum. <ref>M. B. Parkes, ‘The Manuscript of the Leiden Riddle’, Anglo-Saxon England, 1 (1972), 207–17 (p. 208); DOI: 10.1017/S0263675100000168. Length-marks added to Parkes's transcription on the basis of John R. Clark Hall, A Concise Anglo-Saxon Dictionary, 4th rev. edn by Herbet D. Meritt (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1960).</ref>

Ruthwell Cross inscription

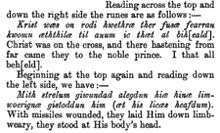

Krist wæs on rodi hwethræ ther fusæ fearran

kwomu æththilæ til anum ic thæt al bih[eald].

Mith strelum giwundad alegdun hiæ hinæ limwoerignæ

gistoddun him (æt his licæs heafdum).

Notes

- In MS. Voss. lat. Q. 166 at the University of Leiden (see article by R. W. Zandvoort in English and Germanic Studies, vol. 3 (1949-50))

- "Ulster-Scots Language". Ulsterscotsagency.com. 2012-01-30. Retrieved 2012-12-30.

- Gray, Alasdair, The Book of Prefaces, Bloomsbury Publishing, London 2000 (2002 edition) ISBN 0-7475-5912-0

- Bell, Laird D T. Northumbrian Culture and Language

- Bell, Laird D T. Northumbrian Culture and Language

- Bede's Death Song: Northumbrian Version

- Browne 1908:297.

Further reading

- Sweet, H., ed. (1885) The Oldest English Texts: glossaries, the Vespasian Psalter, and other works written before A.D. 900. London: for the Early English Text Society

- Sweet, H., ed. (1946) Sweet's Anglo-Saxon Reader; 10th ed., revised by C. T. Onions. Oxford: Clarendon Press. ("Northumbrian texts"—pp. 166–169)