Sex

Organisms of many species are specialized into male and female varieties, each known as a sex.[1][2] Sexual reproduction involves the combining and mixing of genetic traits: specialized cells known as gametes combine to form offspring that inherit traits from each parent. The gametes produced by an organism define its sex: males produce small gametes (e.g. spermatozoa, or sperm, in animals) while females produce large gametes (ova, or egg cells). Individual organisms which produce both male and female gametes are termed hermaphroditic.[2] Gametes can be identical in form and function (known as isogamy), but, in many cases, an asymmetry has evolved such that two different types of gametes (heterogametes) exist (known as anisogamy).

| Part of a series on |

| Sex |

|---|

|

| Biological terms |

| Sexual reproduction |

|

| Sexuality |

Physical differences are often associated with the different sexes of an organism; these sexual dimorphisms can reflect the different reproductive pressures the sexes experience. For instance, mate choice and sexual selection can accelerate the evolution of physical differences between the sexes.

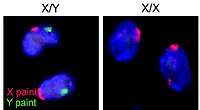

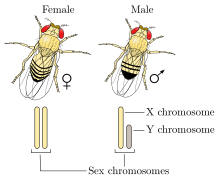

Among humans and other mammals, males typically carry an X and a Y chromosome (XY), whereas females typically carry two X chromosomes (XX), which are a part of the XY sex-determination system. Humans may also be intersex. Other animals have various sex-determination systems, such as the ZW system in birds, the X0 system in insects, and various environmental systems, for example in reptiles and crustaceans. Fungi may also have more complex allelic mating systems, with sexes not accurately described as male, female, or hermaphroditic.[3]

Overview

One of the basic properties of life is reproduction, the capacity to generate new individuals, and sex is an aspect of this process. Life has evolved from simple stages to more complex ones, and so have the reproduction mechanisms. Initially the reproduction was a replicating process that consists in producing new individuals that contain the same genetic information as the original or parent individual. This mode of reproduction is called asexual, and it is still used by many species, particularly unicellular, but it is also very common in multicellular organisms, including many of those with sexual reproduction.[4] In sexual reproduction, the genetic material of the offspring comes from two different individuals. As sexual reproduction developed by way of a long process of evolution, intermediates exist. Bacteria, for instance, reproduce asexually, but undergo a process by which a part of the genetic material of an individual donor is transferred to another recipient.[5]

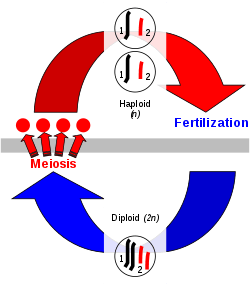

Disregarding intermediates, the basic distinction between asexual and sexual reproduction is the way in which the genetic material is processed. Typically, prior to an asexual division, a cell duplicates its genetic information content, and then divides. This process of cell division is called mitosis. In sexual reproduction, there are special kinds of cells that divide without prior duplication of its genetic material, in a process named meiosis. The resulting cells are called gametes, and contain only half the genetic material of the parent cells. These gametes are the cells that are prepared for the sexual reproduction of the organism.[6] Sex comprises the arrangements that enable sexual reproduction, and has evolved alongside the reproduction system, starting with similar gametes (isogamy) and progressing to systems that have different gamete types, such as those involving a large female gamete (ovum) and a small male gamete (sperm).[7]

In complex organisms, the sex organs are the parts that are involved in the production and exchange of gametes in sexual reproduction. Many species, both plants and animals, have sexual specialization, and their populations are divided into male and female individuals. Conversely, there are also species in which there is no sexual specialization, and the same individuals both contain masculine and feminine reproductive organs, and they are called hermaphrodites. This is very frequent in plants.[8]

Evolution

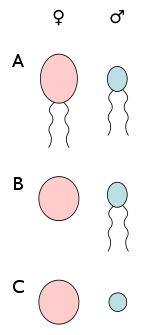

A) anisogamy of motile cells, B) oogamy (egg cell and sperm cell), C) anisogamy of non-motile cells (egg cell and spermatia).

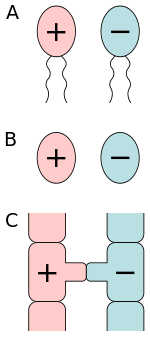

A) isogamy of motile cells, B) isogamy of non-motile cells, C) conjugation.

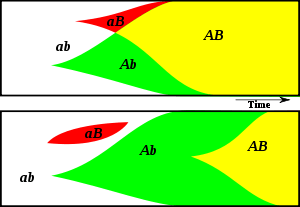

Sexual reproduction first probably evolved about a billion years ago within ancestral single-celled eukaryotes.[9] The reason for the evolution of sex, and the reason(s) it has survived to the present, are still matters of debate. Some of the many plausible theories include: that sex creates variation among offspring, sex helps in the spread of advantageous traits, that sex helps in the removal of disadvantageous traits, and that sex facilitates repair of germ-line DNA.

Sexual reproduction is a process specific to eukaryotes, organisms whose cells contain a nucleus and mitochondria. In addition to animals, plants, and fungi, other eukaryotes (e.g. the malaria parasite) also engage in sexual reproduction. Some bacteria use conjugation to transfer genetic material between cells; while not the same as sexual reproduction, this also results in the mixture of genetic traits.

The defining characteristic of sexual reproduction in eukaryotes is the difference between the gametes and the binary nature of fertilization. Multiplicity of gamete types within a species would still be considered a form of sexual reproduction. However, no third gamete type is known in multicellular plants or animals.[10][11][12]

While the evolution of sex dates to the prokaryote or early eukaryote stage, the origin of chromosomal sex determination may have been fairly early in eukaryotes (see evolution of anisogamy). The ZW sex-determination system is shared by birds, some fish and some crustaceans. XY sex determination is used by most mammals,[13] but also some insects,[14] and plants (Silene latifolia).[15] The X0 sex-determination is found in most arachnids, insects such as silverfish (Apterygota), dragonflies (Paleoptera) and grasshoppers (Exopterygota), and some nematodes, crustaceans, and gastropods.[16][17]

No genes are shared between the avian ZW and mammal XY chromosomes,[18] and from a comparison between chicken and human, the Z chromosome appeared similar to the autosomal chromosome 9 in human, rather than X or Y, suggesting that the ZW and XY sex-determination systems do not share an origin, but that the sex chromosomes are derived from autosomal chromosomes of the common ancestor of birds and mammals. A paper from 2004 compared the chicken Z chromosome with platypus X chromosomes and suggested that the two systems are related.[19]

Sexual reproduction

Sexual reproduction in eukaryotes is a process whereby organisms produce offspring that combine genetic traits from both parents. Chromosomes are passed on from one generation to the next in this process. Each cell in the offspring has half the chromosomes of the mother and half of the father.[20] Genetic traits are contained within the deoxyribonucleic acid (DNA) of chromosomes—by combining one of each type of chromosomes from each parent, an organism is formed containing a doubled set of chromosomes. This double-chromosome stage is called "diploid", while the single-chromosome stage is "haploid". Diploid organisms can, in turn, form haploid cells (gametes) that randomly contain one of each of the chromosome pairs, via meiosis.[21] Meiosis also involves a stage of chromosomal crossover, in which regions of DNA are exchanged between matched types of chromosomes, to form a new pair of mixed chromosomes. Crossing over and fertilization (the recombining of single sets of chromosomes to make a new diploid) result in the new organism containing a different set of genetic traits from either parent.

In many organisms, the haploid stage has been reduced to just gametes specialized to recombine and form a new diploid organism. In plants the diploid organism produces haploid spores that undergo cell division to produce multicellular haploid organisms known as gametophytes that produce haploid gametes at maturity. In either case, gametes may be externally similar, particularly in size (isogamy), or may have evolved an asymmetry such that the gametes are different in size and other aspects (anisogamy).[22] By convention, the larger gamete (called an ovum, or egg cell) is considered female, while the smaller gamete (called a spermatozoon, or sperm cell) is considered male. An individual that produces exclusively large gametes is female, and one that produces exclusively small gametes is male.[23] An individual that produces both types of gametes is a hermaphrodite; in some cases hermaphrodites are able to self-fertilize and produce offspring on their own, without a second organism.[24]

Animals

Most sexually reproducing animals spend their lives as diploid, with the haploid stage reduced to single-cell gametes.[25] The gametes of animals have male and female forms—spermatozoa and egg cells. These gametes combine to form embryos which develop into a new organism.

The male gamete, a spermatozoon (produced in vertebrates within the testes), is a small cell containing a single long flagellum which propels it.[26] Spermatozoa are extremely reduced cells, lacking many cellular components that would be necessary for embryonic development. They are specialized for motility, seeking out an egg cell and fusing with it in a process called fertilization.

Female gametes are egg cells (produced in vertebrates within the ovaries), large immobile cells that contain the nutrients and cellular components necessary for a developing embryo.[27] Egg cells are often associated with other cells which support the development of the embryo, forming an egg. In mammals, the fertilized embryo instead develops within the female, receiving nutrition directly from its mother.

Animals are usually mobile and seek out a partner of the opposite sex for mating. Animals which live in the water can mate using external fertilization, where the eggs and sperm are released into and combine within the surrounding water.[28] Most animals that live outside of water, however, use internal fertilization, transferring sperm directly into the female to prevent the gametes from drying up.

In most birds, both excretion and reproduction is done through a single posterior opening, called the cloaca—male and female birds touch cloaca to transfer sperm, a process called "cloacal kissing".[29] In many other terrestrial animals, males use specialized sex organs to assist the transport of sperm—these male sex organs are called intromittent organs. In humans and other mammals this male organ is the penis, which enters the female reproductive tract (called the vagina) to achieve insemination—a process called sexual intercourse. The penis contains a tube through which semen (a fluid containing sperm) travels. In female mammals the vagina connects with the uterus, an organ which directly supports the development of a fertilized embryo within (a process called gestation).

Because of their motility, animal sexual behavior can involve coercive sex. Traumatic insemination, for example, is used by some insect species to inseminate females through a wound in the abdominal cavity—a process detrimental to the female's health.

Plants

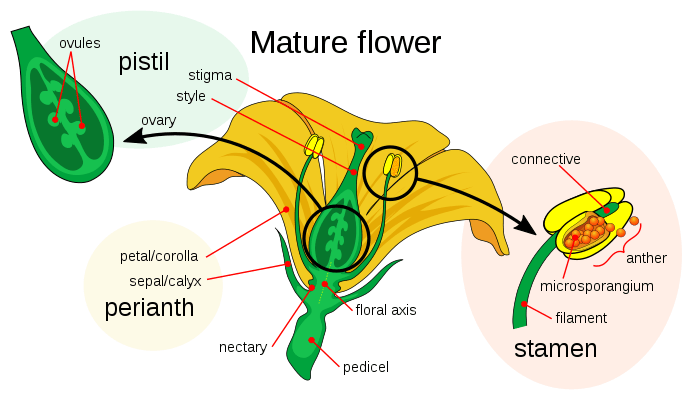

Like animals, plants have specialized male and female gametes.[30] Within seed plants, male gametes are produced by extremely reduced multicellular gametophytes known as pollen. The female gametes of seed plants are contained within ovules; once fertilized by male gametes produced by pollen these form seeds which, like eggs, contain the nutrients necessary for the development of the embryonic plant.

Many plants have flowers and these are the sexual organs of those plants. Flowers are usually hermaphroditic, producing both male and female gametes. The female parts, in the center of a flower, are the pistils, each unit consisting of a carpel, a style and a stigma. One or more of these reproductive units may be merged to form a single compound pistil. Within the carpels are ovules which develop into seeds after fertilization. The male parts of the flower are the stamens: these consist of long filaments arranged between the pistil and the petals that produce pollen in anthers at their tips. When a pollen grain lands upon the stigma on top of a carpel's style, it germinates to produce a pollen tube that grows down through the tissues of the style into the carpel, where it delivers male gamete nuclei to fertilize an ovule that eventually develops into a seed.

In pines and other conifers the sex organs are conifer cones and have male and female forms. The more familiar female cones are typically more durable, containing ovules within them. Male cones are smaller and produce pollen which is transported by wind to land in female cones. As with flowers, seeds form within the female cone after pollination.

Because plants are immobile, they depend upon passive methods for transporting pollen grains to other plants. Many plants, including conifers and grasses, produce lightweight pollen which is carried by wind to neighboring plants. Other plants have heavier, sticky pollen that is specialized for transportation by animals. The plants attract these insects or larger animals such as humming birds and bats with nectar-containing flowers. These animals transport the pollen as they move to other flowers, which also contain female reproductive organs, resulting in pollination.

Fungi

Most fungi reproduce sexually, having both a haploid and diploid stage in their life cycles. These fungi are typically isogamous, lacking male and female specialization: haploid fungi grow into contact with each other and then fuse their cells. In some of these cases, the fusion is asymmetric, and the cell which donates only a nucleus (and not accompanying cellular material) could arguably be considered "male".[31] Fungi may also have more complex allelic mating systems, with other sexes not accurately described as male, female, or hermaphroditic.[3]

Some fungi, including baker's yeast, have mating types that create a duality similar to male and female roles. Yeast with the same mating type will not fuse with each other to form diploid cells, only with yeast carrying the other mating type.[32]

Many species of higher fungi produce mushrooms as part of their sexual reproduction. Within the mushroom diploid cells are formed, later dividing into haploid spores. The height of the mushroom aids the dispersal of these sexually produced offspring.

Sex determination

The most basic sexual system is one in which all organisms are hermaphrodites, producing both male and female gametes. This is true of some animals (e.g. snails) and the majority of flowering plants.[33] In many cases, however, specialization of sex has evolved such that some organisms produce only male or only female gametes. The biological cause for an organism developing into one sex or the other is called sex determination. The cause may be genetic or non-genetic. Within animals and other organisms that have genetic sex determination systems, the determining factor may be the presence of a sex chromosome or other genetic differences. In plants also, such as the liverwort Marchantia polymorpha and the flowering plant genus Silene that have sexual dimorphism (dioicy or dioicy, respectively), sex may be determined by sex chromosomes.[34] Non-genetic systems may use environmental cues, such as the temperature during early development in crocodiles, to determine the sex of the offspring.[35]

In the majority of species with sex specialization, organisms are either male (producing only male gametes) or female (producing only female gametes). Exceptions are common—for example, the roundworm C. elegans has an hermaphrodite and a male sex (a system called androdioecy).

Sometimes an organism's development is intermediate between male and female, a condition called intersex. Sometimes intersex individuals are called "hermaphrodite"; but, unlike biological hermaphrodites, intersex individuals are unusual cases and are not typically fertile in both male and female aspects.

Genetic

In genetic sex-determination systems, an organism's sex is determined by the genome it inherits. Genetic sex-determination usually depends on asymmetrically inherited sex chromosomes which carry genetic features that influence development; sex may be determined either by the presence of a sex chromosome or by how many the organism has. Genetic sex-determination, because it is determined by chromosome assortment, usually results in a 1:1 ratio of male and female offspring.

Humans and other mammals have an XY sex-determination system: the Y chromosome carries factors responsible for triggering male development. The "default sex," in the absence of a Y chromosome, is female-like. Thus, XX mammals are female and XY are male. In humans, biological sex is determined by five factors present at birth: the presence or absence of a Y chromosome (which alone determines the individual's genetic sex), the type of gonads, the sex hormones, the internal reproductive anatomy (such as the uterus in females), and the external genitalia.[36][37]

XY sex determination is found in other organisms, including the common fruit fly and some plants.[33] In some cases, including in the fruit fly, it is the number of X chromosomes that determines sex rather than the presence of a Y chromosome (see below).

In birds, which have a ZW sex-determination system, the opposite is true: the W chromosome carries factors responsible for female development, and default development is male.[38] In this case ZZ individuals are male and ZW are female. The majority of butterflies and moths also have a ZW sex-determination system. In both XY and ZW sex determination systems, the sex chromosome carrying the critical factors is often significantly smaller, carrying little more than the genes necessary for triggering the development of a given sex.[39]

Many insects use a sex determination system based on the number of sex chromosomes. This is called X0 sex-determination—the 0 indicates the absence of the sex chromosome. All other chromosomes in these organisms are diploid, but organisms may inherit one or two X chromosomes. In field crickets, for example, insects with a single X chromosome develop as male, while those with two develop as female.[40] In the nematode C. elegans most worms are self-fertilizing XX hermaphrodites, but occasionally abnormalities in chromosome inheritance regularly give rise to individuals with only one X chromosome—these X0 individuals are fertile males (and half their offspring are male).[41]

Other insects, including honey bees and ants, use a haplodiploid sex-determination system.[42] In this case, diploid individuals are generally female, and haploid individuals (which develop from unfertilized eggs) are male. This sex-determination system results in highly biased sex ratios, as the sex of offspring is determined by fertilization rather than the assortment of chromosomes during meiosis.

Nongenetic

For many species, sex is not determined by inherited traits, but instead by environmental factors experienced during development or later in life. Many reptiles have temperature-dependent sex determination: the temperature embryos experience during their development determines the sex of the organism. In some turtles, for example, males are produced at lower incubation temperatures than females; this difference in critical temperatures can be as little as 1–2 °C.

Many fish change sex over the course of their lifespan, a phenomenon called sequential hermaphroditism. In clownfish, smaller fish are male, and the dominant and largest fish in a group becomes female. In many wrasses the opposite is true—most fish are initially female and become male when they reach a certain size. Sequential hermaphrodites may produce both types of gametes over the course of their lifetime, but at any given point they are either female or male.

In some ferns the default sex is hermaphrodite, but ferns which grow in soil that has previously supported hermaphrodites are influenced by residual hormones to instead develop as male.[43]

Sexual dimorphism

Many animals and some plants have differences between the male and female sexes in size and appearance, a phenomenon called sexual dimorphism. Sex differences in humans include, generally, a larger size and more body hair in men; women have breasts, wider hips, and a higher body fat percentage. In other species, the differences may be more extreme, such as differences in coloration or bodyweight.

Sexual dimorphisms in animals are often associated with sexual selection—the competition between individuals of one sex to mate with the opposite sex.[44] Antlers in male deer, for example, are used in combat between males to win reproductive access to female deer. In many cases the male of a species is larger than the female. Mammal species with extreme sexual size dimorphism tend to have highly polygynous mating systems—presumably due to selection for success in competition with other males—such as the elephant seals. Other examples demonstrate that it is the preference of females that drive sexual dimorphism, such as in the case of the stalk-eyed fly.[45]

Other animals, including most insects and many fish, have larger females. This may be associated with the cost of producing egg cells, which requires more nutrition than producing sperm—larger females are able to produce more eggs.[46] For example, female southern black widow spiders are typically twice as long as the males.[47] Occasionally this dimorphism is extreme, with males reduced to living as parasites dependent on the female, such as in the anglerfish. Some plant species also exhibit dimorphism in which the females are significantly larger than the males, such as in the moss Dicranum[48] and the liverwort Sphaerocarpos.[49] There is some evidence that, in these genera, the dimorphism may be tied to a sex chromosome,[49][50] or to chemical signalling from females.[51]

In birds, males often have a more colourful appearance and may have features (like the long tail of male peacocks) that would seem to put the organism at a disadvantage (e.g. bright colors would seem to make a bird more visible to predators). One proposed explanation for this is the handicap principle.[52] This hypothesis says that, by demonstrating he can survive with such handicaps, the male is advertising his genetic fitness to females—traits that will benefit daughters as well, who will not be encumbered with such handicaps.

See also

References

- Angus Stevenson, Maurice Waite (2011). Concise Oxford English Dictionary: Book & CD-ROM Set. OUP Oxford. p. 1302. ISBN 978-0-19-960110-3. Retrieved 23 March 2018.

Sex: Either of the two main categories (male and female) into which humans and most other living things are divided on the basis of their reproductive functions. The fact of belonging to one of these categories. The group of all members of either sex.

CS1 maint: uses authors parameter (link) - William K. Purves, David E. Sadava, Gordon H. Orians, H. Craig Heller (2000). Life: The Science of Biology. Macmillan. p. 736. ISBN 978-0-7167-3873-2. Retrieved 23 March 2018.

A single body can function as both male and female. Sexual reproduction requires both male and female haploid gametes. In most species, these gametes are produced by individuals that are either male or female. Species that have male and female members are called dioecious (from the Greek for 'two houses'). In some species, a single individual may possess both female and male reproductive systems. Such species are called monoecious ("one house") or hermaphroditic.

CS1 maint: uses authors parameter (link) - Watkinson, S.C.; Boddy, L.; Money, N. (2015). The Fungi. Elsevier Science. p. 115. ISBN 978-0-12-382035-8. Retrieved 18 February 2018.

- Raven, P.H.; et al. Biology of Plants (7th ed.). NY: Freeman and Company Publishers.

- Holmes, R.K.; et al. (1996). Genetics: Conjugation (4th ed.). University of Texas.

- Freeman, Scott (2005). Biological Science (3rd ed.). Pearson Prentice Hall.

- Dusenbery, David B. (2009). Living at Micro Scale. Cambridge, Massachusetts: Harvard University Press.

- Beukeboom, L., and other (2014). The Evolution of Sex Determination. Oxford University Press.

- "Book Review for Life: A Natural History of the First Four Billion Years of Life on Earth". Jupiter Scientific. Retrieved 7 April 2008.

- Schaffer, Amanda (updated 27 September 2007) "Pas de Deux: Why Are There Only Two Sexes?", Slate.

- Hurst, Laurence D. (1996). "Why are There Only Two Sexes?". Proceedings: Biological Sciences. 263 (1369): 415–422. doi:10.1098/rspb.1996.0063. JSTOR 50723.

- Haag, E.S. (2007). "Why two sexes? Sex determination in multicellular organisms and protistan mating types". Seminars in Cell and Developmental Biology. 18 (3): 348–349. doi:10.1016/j.semcdb.2007.05.009. PMID 17644371.

- Wallis MC, Waters PD, Graves JA (2008). "Sex determination in mammals--before and after the evolution of SRY". Cell. Mol. Life Sci. 65 (20): 3182–3195. doi:10.1007/s00018-008-8109-z. PMID 18581056.

- Kaiser VB, Bachtrog D (2010). "Evolution of sex chromosomes in insects". Annu. Rev. Genet. 44: 91–112. doi:10.1146/annurev-genet-102209-163600. PMC 4105922. PMID 21047257.

- Guttman DS, Charlesworth D (1998). "An X-linked gene with a degenerate Y-linked homologue in a dioecious plant". Nature. 393 (6682): 263–266. Bibcode:1998Natur.393..263G. doi:10.1038/30492. PMID 9607762.

- Bull, James J.; Evolution of sex determining mechanisms; p. 17 ISBN 0-8053-0400-2

- Thirot-Quiévreux, Catherine; ‘Advances in Chromosomal Studies of Gastropod Molluscs’; Journal of Molluscan Studies, vol. 69 (2003), pp. 187–201

- Stiglec, R.; Ezaz, T.; Graves, J.A. (2007). "A new look at the evolution of avian sex chromosomes". Cytogenet. Genome Res. 117 (1–4): 103–109. doi:10.1159/000103170. PMID 17675850.

- Grützner, F.; Rens, W.; Tsend-Ayush, E.; El-Mogharbel, N.; O'Brien, P.C.M.; Jones, R.C.; Ferguson-Smith, M.A.; Marshall, J.A. (2004). "In the platypus a meiotic chain of ten sex chromosomes shares genes with the bird Z and mammal X chromosomes". Nature. 432 (7019): 913–917. Bibcode:2004Natur.432..913G. doi:10.1038/nature03021. PMID 15502814.

- Alberts et al. (2002), U.S. National Institutes of Health, "V. 20. The Benefits of Sex".

- Alberts et al. (2002), "V. 20. Meiosis", U.S. NIH, V. 20. Meiosis.

- Gilbert (2000), "1.2. Multicellularity: Evolution of Differentiation". 1.2.Mul, NIH.

- Gee, Henry (22 November 1999). "Size and the single sex cell". Nature. Retrieved 4 June 2018.

- Alberts et al. (2002), "V. 21. Caenorhabditis Elegans: Development as Indiv. Cell", U.S. NIH, V. 21. Caenorhabditis.

- Alberts et al. (2002), "3. Mendelian genetics in eukaryotic life cycles", U.S. NIH, 3. Mendelian/eukaryotic.

- Alberts et al. (2002), "V.20. Sperm", U.S. NIH, V.20. Sperm.

- Alberts et al. (2002), "V.20. Eggs", U.S. NIH, V.20. Eggs.

- Alberts et al. (2002), "V.20. Fertilization", U.S. NIH, V.20. Fertilization.

- Ritchison, G. "Avian Reproduction". people.eku.edu. Eastern Kentucky University. Retrieved 3 April 2008.

- Gilbert (2000), "4.20. Gamete Production in Angiosperms", U.S. NIH, 4.20. Gamete/Angio..

- Nick Lane (2005). Power, Sex, Suicide: Mitochondria and the Meaning of Life. Oxford University Press. pp. 236–237. ISBN 978-0-19-280481-5.

- Matthew P. Scott; Paul Matsudaira; Harvey Lodish; James Darnell; Lawrence Zipursky; Chris A. Kaiser; Arnold Berk; Monty Krieger (2000). Molecular Cell Biology (Fourth ed.). WH Freeman and Co. ISBN 978-0-7167-4366-8.14.1. Cell-Type Specification and Mating-Type Conversion in Yeast

- Dellaporta, S.L.; Calderon-Urrea, A. (1993). "Sex Determination in Flowering Plants". The Plant Cell. 5 (10): 1241–1251. doi:10.1105/tpc.5.10.1241. JSTOR 3869777. PMC 160357. PMID 8281039.

- Tanurdzic, Milos; Banks, Jo Ann (2004). "Sex-determining mechanisms in land plants". The Plant Cell. 16: S61–S71. doi:10.1105/tpc.016667. PMC 2643385. PMID 15084718.

- Warner, D.A.; Shine, R. (2008). "The adaptive significance of temperature-dependent sex determination in a reptile". Nature. 451 (7178): 566–568. doi:10.1038/nature06519. PMID 18204437.

- Knox, David; Schacht, Caroline. Choices in Relationships: An Introduction to Marriage and the Family. 11 ed. Cengage Learning; 10 October 2011 [cited 17 June 2013]. ISBN 978-1-111-83322-0. pp. 64–66.

- Raveenthiran, V (2017). "Neonatal Sex Assignment in Disorders of Sex Development: A Philosophical Introspection". Journal of Neonatal Surgery. 6 (3): 58. doi:10.21699/jns.v6i3.604. ISSN 2226-0439.

- Smith, C.A.; Katza, M.; Sinclair, A.H. (2003). "DMRT1 Is Upregulated in the Gonads During Female-to-Male Sex Reversal in ZW Chicken Embryos". Biology of Reproduction. 68 (2): 560–570. doi:10.1095/biolreprod.102.007294. PMID 12533420.

- "Evolution of the Y Chromosome". Annenberg Media. Annenberg Media. Archived from the original on 4 November 2004. Retrieved 1 April 2008.

- Yoshimura, A. (2005). "Karyotypes of two American field crickets: Gryllus rubens and Gryllus sp. (Orthoptera: Gryllidae)". Entomological Science. 8 (3): 219–222. doi:10.1111/j.1479-8298.2005.00118.x.

- Riddle, D.L.; Blumenthal, T.; Meyer, B.J.; Priess, J.R. (1997). C. Elegans II. Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press. ISBN 978-0-87969-532-3. 9.II. Sexual Dimorphism

- Charlesworth, B. (2003). "Sex Determination in the Honeybee". Cell. 114 (4): 397–398. doi:10.1016/S0092-8674(03)00610-X. PMID 12941267.

- Tanurdzic, M.; Banks, J.A. (2004). "Sex-Determining Mechanisms in Land Plants". The Plant Cell. 16 (Suppl): S61–S71. doi:10.1105/tpc.016667. PMC 2643385. PMID 15084718.

- Darwin, C. (1871). The Descent of Man. Murray, London. ISBN 978-0-8014-2085-6.

- Wilkinson, G.S.; Reillo, P.R. (22 January 1994). "Female choice response to artificial selection on an exaggerated male trait in a stalk-eyed fly" (PDF). Proceedings of the Royal Society B. 225 (1342): 1–6. Bibcode:1994RSPSB.255....1W. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.574.2822. doi:10.1098/rspb.1994.0001. Archived from the original (PDF) on 10 September 2006.

- Stuart-Smith, J.; Swain, R.; Stuart-Smith, R.; Wapstra, E. (2007). "Is fecundity the ultimate cause of female-biased size dimorphism in a dragon lizard?" (PDF). Journal of Zoology. 273 (3): 266–272. doi:10.1111/j.1469-7998.2007.00324.x.

- "Southern black widow spider". Extension Entomology. Insects.tamu.edu. Archived from the original on 31 August 2003. Retrieved 8 August 2012.

- Shaw, A. Jonathan (2000). "Population ecology, population genetics, and microevolution". In A. Jonathan Shaw; Bernard Goffinet (eds.). Bryophyte Biology. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. pp. 379–380. ISBN 978-0-521-66097-6.

- Schuster, Rudolf M. (1984). "Comparative Anatomy and Morphology of the Hepaticae". New Manual of Bryology. 2. Nichinan, Miyazaki, Japan: The Hattori botanical Laboratory. p. 891.

- Crum, Howard A.; Anderson, Lewis E. (1980). Mosses of Eastern North America. 1. New York: Columbia University Press. p. 196. ISBN 978-0-231-04516-2.

- Briggs, D.A. (1965). "Experimental taxonomy of some British species of genus Dicranum". New Phytologist. 64 (3): 366–386. doi:10.1111/j.1469-8137.1965.tb07546.x.

- Zahavi, Amotz; Zahavi, Avishag (1997). The handicap principle: a missing piece of Darwin's puzzle. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-510035-8.

Further reading

- Ainsworth, Claire (2015). (19 February 2015). "Sex redefined: The idea of two sexes is simplistic. Biologists now think there is a wider spectrum than that". Nature. 518 (7539): 288–291. doi:10.1038/518288a. PMID 25693544.

- Arnqvist, G.; Rowe, L. (2005). Sexual conflict. Princeton University Press. ISBN 978-0-691-12217-5.

- Alberts, B.; Johnson, A.; Lewis, J.; Raff, M.; Roberts, K.; Walter, P. (2002). Molecular Biology of the Cell (4th ed.). New York: Garland Science. ISBN 978-0-8153-3218-3.

- Ellis, Havelock (1933). Psychology of Sex. London: W. Heinemann Medical Books. N.B.: One of many books by this pioneering authority on aspects of human sexuality.

- Gilbert, S.F. (2000). Developmental Biology (6th ed.). Sinauer Associates, Inc. ISBN 978-0-87893-243-6.

- Maynard-Smith, J. (1978). The Evolution of Sex. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-29302-0.

External links

- Human Sexual Differentiation by P. C. Sizonenko