Transgender

Transgender people have a gender identity or gender expression that differs from their sex assigned at birth.[1][2][3] Some transgender people who desire medical assistance to transition from one sex to another identify as transsexual.[4][5] Transgender, often shortened as trans, is also an umbrella term. In addition to including people whose gender identity is the opposite of their assigned sex (trans men and trans women), it may include people who are not exclusively masculine or feminine (people who are non-binary or genderqueer, including bigender, pangender, genderfluid, or agender).[2][6][7] Other definitions of transgender also include people who belong to a third gender, or else conceptualize transgender people as a third gender.[8][9] The term transgender may be defined very broadly to include cross-dressers.[10]

| Part of a series on |

| Transgender topics |

|---|

|

|

|

Health care and medicine |

|

Rights issues

|

|

Society and culture

|

|

By country

|

|

|

Being transgender is independent of sexual orientation.[11] Transgender people may identify as heterosexual, homosexual, bisexual, asexual, or may decline to label their sexual orientation. The term transgender is also distinguished from intersex, a term that describes people born with physical sex characteristics "that do not fit typical binary notions of male or female bodies".[12] The opposite of transgender is cisgender, which describes persons whose gender identity or expression matches their assigned sex.[13]

The degree to which individuals feel genuine, authentic, and comfortable within their external appearance and accept their genuine identity has been called transgender congruence.[14] Many transgender people experience gender dysphoria, and some seek medical treatments such as hormone replacement therapy, sex reassignment surgery, or psychotherapy.[15] Not all transgender people desire these treatments, and some cannot undergo them for financial or medical reasons.[15][16]

Many transgender people face discrimination in the workplace[17] and in accessing public accommodations[18] and healthcare.[19] In many places, they are not legally protected from discrimination.[20]

Evolution of transgender terminology

.jpg)

Psychiatrist John F. Oliven of Columbia University coined the term transgender in his 1965 reference work Sexual Hygiene and Pathology,[21] writing that the term which had previously been used, transsexualism, "is misleading; actually, 'transgenderism' is meant, because sexuality is not a major factor in primary transvestism."[22][23] The term transgender was then popularized with varying definitions by various transgender, transsexual, and transvestite people, including Virginia Prince,[4] who used it in the December 1969 issue of Transvestia, a national magazine for cross dressers she founded.[24] By the mid-1970s both trans-gender and trans people were in use as umbrella terms,[note 1] and transgenderist was used to refer to people who wanted to live cross-gender without sex reassignment surgery (SRS).[25] By 1976, transgenderist was abbreviated as TG in educational materials.[26]

By 1984, the concept of a "transgender community" had developed, in which transgender was used as an umbrella term.[27] In 1985, Richard Elkins established the "Trans-Gender Archive" at the University of Ulster.[24] By 1992, the International Conference on Transgender Law and Employment Policy defined transgender as an expansive umbrella term including "transsexuals, transgenderists, cross dressers", and anyone transitioning.[28] Leslie Feinberg's pamphlet, "Transgender Liberation: A Movement Whose Time has Come", circulated in 1992, identified transgender as a term to unify all forms of gender nonconformity; in this way transgender has become synonymous with queer.[29]

Between the mid-1990s and the early 2000s, the primary terms used under the transgender umbrella were "female to male" (FtM) for men who transitioned from female to male, and "male to female" (MtF) for women who transitioned from male to female. These terms have now been superseded by "trans man" and "trans woman", respectively, and the terms "trans-masculine" or "trans-feminine" are increasingly in use.[30] This shift in preference from terms highlighting biological sex ("transsexual", "FtM") to terms highlighting gender identity and expression ("transgender", "trans woman") reflects a broader shift in the understanding of transgender people's sense of self and the increasing recognition of those who decline medical reassignment as part of the transgender community.[30]

Health-practitioner manuals, professional journalistic style guides, and LGBT advocacy groups advise the adoption by others of the name and pronouns identified by the person in question, including present references to the transgender person's past.[31][32] Many also note that transgender should be used as an adjective, not a noun (for example, "Max is transgender" or "Max is a transgender man", not "Max is a transgender"), and that transgender should be used, not transgendered.[33][34][35]

In contrast, people whose sense of personal identity corresponds to the sex and gender assigned to them at birth – that is, those who are neither transgender nor non-binary or genderqueer – are called cisgender.[36]

Transsexual and its relationship to transgender

The term transsexual was introduced to English in 1949 by David Oliver Cauldwell[note 2] and popularized by Harry Benjamin in 1966, around the same time transgender was coined and began to be popularized.[4] Since the 1990s, transsexual has generally been used to refer to the subset of transgender people[4][37][38] who desire to transition permanently to the gender with which they identify and who seek medical assistance (for example, sex reassignment surgery) with this.

Distinctions between the terms transgender and transsexual are commonly based on distinctions between gender (psychological, social) and sex (physical).[39][40] Hence transsexuality may be said to deal more with physical aspects of one's sex, while transgender considerations deal more with one's psychological gender disposition or predisposition, as well as the related social expectations that may accompany a given gender role.[41] Many transgender people reject the term transsexual.[5][42][43] Christine Jorgensen publicly rejected transsexual in 1979 and instead identified herself in newsprint as trans-gender, saying, "gender doesn't have to do with bed partners, it has to do with identity."[44][45] This refers to the concern that transsexual implies something to do with sexuality, when it is actually about gender identity.[46][note 3] Some transsexual people object to being included in the transgender umbrella.[47][48][49][50]

In his 2007 book Transgender, an Ethnography of a Category, anthropologist David Valentine asserts that transgender was coined and used by activists to include many people who do not necessarily identify with the term and states that people who do not identify with the term transgender should not be included in the transgender spectrum.[47] Leslie Feinberg likewise asserts that transgender is not a self-identifier (for some people) but a category imposed by observers to understand other people.[48] The Transgender Health Program (THP) at Fenway Health in Boston notes that there are no universally-accepted definitions, and terminology confusion is common because terms that were popular at the turn of the 21st century may now be deemed offensive. The THP recommends that clinicians ask clients what terminology they prefer, and avoid the term transsexual unless they are sure that a client is comfortable with it.[46]

Harry Benjamin invented a classification system for transsexuals and transvestites, called the Sex Orientation Scale (SOS), in which he assigned transsexuals and transvestites to one of six categories based on their reasons for cross-dressing and the relative urgency of their need (if any) for sex reassignment surgery.[51] Contemporary views on gender identity and classification differ markedly from Harry Benjamin's original opinions.[52] Sexual orientation is no longer regarded a criterion for diagnosis, or for distinction between transsexuality, transvestism and other forms of gender variant behavior and expression. Benjamin's scale was designed for use with trans women, and trans men's identities do not align with its categories.[53]

Other categories

These comprise genderqueer/non-binary genders, cross-dressers/transvestites, drag kings and drag queens, and intersex persons.

Non-binary, including androgynous and bigender

Genderqueer or non-binary gender identities are not specifically male or female. They can be agender, androgynous, bigender, pangender, or genderfluid,[54] and exist outside of cisnormativity.[55][56] Bigender and androgynous are overlapping categories; bigender individuals may identify as moving between male and female roles (genderfluid) or as being both masculine and feminine simultaneously (androgynous), and androgynes may similarly identify as beyond gender or genderless (postgender, agender), between genders (intergender), moving across genders (genderfluid), or simultaneously exhibiting multiple genders (pangender).[57] Androgyne is also sometimes used as a medical synonym for an intersex person.[58] Non-binary gender identities are independent of sexual orientation.[59][60]

Transvestite or cross-dresser

A transvestite is a person who cross-dresses, or dresses in clothes typically associated with the gender opposite the one they were assigned at birth.[61][62] The term transvestite is used as a synonym for the term cross-dresser,[63][64] although cross-dresser is generally considered the preferred term.[64][65] The term cross-dresser is not exactly defined in the relevant literature. Michael A. Gilbert, professor at the Department of Philosophy, York University, Toronto, offers this definition: "[A cross-dresser] is a person who has an apparent gender identification with one sex, and who has and certainly has been birth-designated as belonging to [that] sex, but who wears the clothing of the opposite sex because it is that of the opposite sex."[66] This definition excludes people "who wear opposite sex clothing for other reasons," such as "those female impersonators who look upon dressing as solely connected to their livelihood, actors undertaking roles, individual males and females enjoying a masquerade, and so on. These individuals are cross dressing but are not cross dressers."[67] Cross-dressers may not identify with, want to be, or adopt the behaviors or practices of the opposite gender and generally do not want to change their bodies medically or surgically. The majority of cross-dressers identify as heterosexual.[68]

The term transvestite and the associated outdated term transvestism are conceptually different from the term transvestic fetishism, as transvestic fetishist refers to those who intermittently use clothing of the opposite gender for fetishistic purposes.[69][70] In medical terms, transvestic fetishism is differentiated from cross-dressing by use of the separate codes 302.3[70] in the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM) and F65.1[69] in the ICD.

Drag kings and queens

Drag is clothing and makeup worn on special occasions for performing or entertaining, unlike those who are transgender or who cross-dress for other reasons. Drag performance includes overall presentation and behavior in addition to clothing and makeup. Drag can be theatrical, comedic, or grotesque. Drag queens have been considered caricatures of women by second-wave feminism. Drag artists have a long tradition in LGBT culture.

Generally the term drag queen covers men doing female drag, drag king covers women doing male drag, and faux queen covers women doing female drag.[71][72] Nevertheless, there are drag artists of all genders and sexualities who perform for various reasons. Drag performers are not inherently transgender. Some drag performers, transvestites, and people in the gay community have embraced the pornographically-derived term tranny for drag queens or people who engage in transvestism or cross-dressing; however, this term is widely considered offensive if applied to transgender people.

LGBT community

The concepts of gender identity and transgender identity differ from that of sexual orientation.[73] Sexual orientation is an individual's enduring physical, romantic, emotional, or spiritual attraction to another person, while gender identity is one's personal sense of being a man or a woman.[33] Transgender people have more or less the same variety of sexual orientations as cisgender people.[74] In the past, the terms homosexual and heterosexual were incorrectly used to label transgender individuals' sexual orientation based on their birth sex.[75] Professional literature often uses terms such as attracted to men (androphilic), attracted to women (gynephilic), attracted to both (bisexual), or attracted to neither (asexual) to describe a person's sexual orientation without reference to their gender identity.[76] Therapists are coming to understand the necessity of using terms with respect to their clients' gender identities and preferences.[77] For example, a person who is assigned male at birth, transitions to female, and is attracted to men would be identified as heterosexual.

Despite the distinction between sexual orientation and gender, throughout history the gay, lesbian, and bisexual subculture was often the only place where gender-variant people were socially accepted in the gender role they felt they belonged to; especially during the time when legal or medical transitioning was almost impossible. This acceptance has had a complex history. Like the wider world, the gay community in Western societies did not generally distinguish between sex and gender identity until the 1970s, and often perceived gender-variant people more as homosexuals who behaved in a gender-variant way than as gender-variant people in their own right. In addition, the role of the transgender community in the history of LGBT rights is often overlooked, as shown in Transforming History.[78]

Sexual orientation of transgender people

In 2015, the American National Center for Transgender Equality conducted a National Transgender Discrimination Survey. Of the 27,715 transgender and non-binary people who took the survey, 21% said the term queer best described their sexual orientation, 18% said "pansexual", 16% said gay, lesbian, or same-gender-loving, 15% said straight, 14% said bisexual, and 10% said asexual.[79] And a 2019 survey of trans and non-binary people in Canada called Trans PULSE Canada showed that out of 2,873 respondents, when it came to sexual orientation, 13% identified as asexual, 28% identified as bisexual, 13% identified as gay, 15% identified as lesbian, 31% identified as pansexual, 8% identified as straight or heterosexual, 4% identified as two-spirit, and 9% identified as unsure or questioning.[80]

Healthcare

Mental healthcare

Most mental health professionals recommend therapy for internal conflicts about gender identity or discomfort in an assigned gender role, especially if one desires to transition. People who experience discord between their gender and the expectations of others or whose gender identity conflicts with their body may benefit by talking through their feelings in depth; however, research on gender identity with regard to psychology, and scientific understanding of the phenomenon and its related issues, is relatively new.[81] The terms transsexualism, dual-role transvestism, gender identity disorder in adolescents or adults, and gender identity disorder not otherwise specified are listed as such in the International Statistical Classification of Diseases (ICD) by the WHO or the American Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM) under codes F64.0, F64.1, 302.85, and 302.6 respectively.[82]

The validity of the diagnosis and its presence in the forthcoming ICD-11 is debated. France removed gender identity disorder as a diagnosis by decree in 2010,[83][84] but according to French trans rights organizations, beyond the impact of the announcement itself, nothing changed.[85] In 2017, the Danish parliament abolished the F64 Gender identity disorders. The DSM-5 refers to the topic as gender dysphoria (GD) while reinforcing the idea that being transgender is not considered a mental illness.[86]

Transgender people may meet the criteria for a diagnosis of gender dysphoria "only if [being transgender] causes distress or disability."[87] This distress may manifest as depression or inability to work and form healthy relationships with others. This diagnosis is often misinterpreted as implying that all transgender people suffer from GD, which has confused transgender people and those who seek to either criticize or affirm them. Transgender people who are comfortable with their gender and whose gender is not directly causing inner frustration or impairing their functioning do not suffer from GD. Moreover, GD is not necessarily permanent and is often resolved through therapy or transitioning. Feeling oppressed by the negative attitudes and behaviors of such others as legal entities does not indicate GD. GD does not imply an opinion of immorality; the psychological establishment holds that people with any kind of mental or emotional problem should not receive stigma. The solution for GD is whatever will alleviate suffering and restore functionality; this solution often, but not always, consists of undergoing a gender transition.[81]

Clinical training lacks relevant information needed in order to adequately help transgender clients, which results in a large number of practitioners who are not prepared to sufficiently work with this population of individuals.[88] Many mental healthcare providers know little about transgender issues. Those who seek help from these professionals often educate the professional without receiving help.[81] This solution usually is good for transsexual people but is not the solution for other transgender people, particularly non-binary people who lack an exclusively male or female identity. Instead, therapists can support their clients in whatever steps they choose to take to transition or can support their decision not to transition while also addressing their clients' sense of congruence between gender identity and appearance.[14]

Acknowledgment of the lack of clinical training has increased; however, research on the specific problems faced by the transgender community in mental health has focused on diagnosis and clinicians' experiences instead of transgender clients' experiences.[89] Therapy was not always sought by transgender people due to mental health needs. Prior to the seventh version of the Standards of Care (SOC), an individual had to be diagnosed with gender identity disorder in order to proceed with hormone treatments or sexual reassignment surgery. The new version decreased the focus on diagnosis and instead emphasized the importance of flexibility in order to meet the diverse health care needs of transsexual, transgender, and all gender-nonconforming people.[90]

The reasons for seeking mental health services vary according to the individual. A transgender person seeking treatment does not necessarily mean their gender identity is problematic. The emotional strain of dealing with stigma and experiencing transphobia pushes many transgender people to seek treatment to improve their quality of life, as one trans woman reflected: "Transgendered individuals are going to come to a therapist and most of their issues have nothing to do, specifically, with being transgendered. It has to do because they've had to hide, they've had to lie, and they've felt all of this guilt and shame, unfortunately usually for years!"[89] Many transgender people also seek mental health treatment for depression and anxiety caused by the stigma attached to being transgender, and some transgender people have stressed the importance of acknowledging their gender identity with a therapist in order to discuss other quality-of-life issues.[89] Others regret having undergone the procedure and wish to detransition.[91]

Problems still remain surrounding misinformation about transgender issues that hurt transgender people's mental health experiences. One trans man who was enrolled as a student in a psychology graduate program highlighted the main concerns with modern clinical training: "Most people probably are familiar with the term transgender, but maybe that's it. I don’t think I've had any formal training just going through [clinical] programs . . . I don’t think most [therapists] know. Most therapists—Master's degree, PhD level—they've had . . . one diversity class on GLBT issues. One class out of the huge diversity training. One class. And it was probably mostly about gay lifestyle."[89] Many health insurance policies do not cover treatment associated with gender transition, and numerous people are under- or uninsured, which raises concerns about the insufficient training most therapists receive prior to working with transgender clients, potentially increasing financial strain on clients without providing the treatment they need.[89] Many clinicians who work with transgender clients only receive mediocre training on gender identity, but introductory training on interacting with transgender people has recently been made available to health care professionals to help remove barriers and increase the level of service for the transgender population.[92]

The issues around psychological classifications and associated stigma (whether based in paraphilia or not) of cross-dressers, transsexual men and women (and lesbian and gay children, who may resemble trans children early in life) have become more complex since CAMH (Centre for Addiction and Mental Health) colleagues Kenneth Zucker and Ray Blanchard were announced to be serving on the DSM-V's Sexual and Gender Identity Disorders Work Group.[93] CAMH aims to "cure" transgender people of their "disorder", especially in children. Within the trans community, this intention has mostly produced shock and outrage with attempts to organize other responses.[94] In February 2010, France became the first country in the world to remove transgender identity from the list of mental diseases.[95][96]

A 2014 study carried out by the Williams Institute (a UCLA think tank) found that 41% of transgender people had attempted suicide, with the rate being higher among people who experienced discrimination in access to housing or healthcare, harassment, physical or sexual assault, or rejection by family.[97] A 2019 follow-up study found that transgender people who wanted and received gender-affirming medical care had substantially lower rates of suicidal thoughts and attempts.[98]

Autism is more common in people who are gender dysphoric. It is not known whether there is a biological basis. This may be due to the fact that people on the autism spectrum are less concerned with societal disapproval, and feel less fear or inhibition about coming out as trans than others.[99]

Physical healthcare

Medical and surgical procedures exist for transsexual and some transgender people, though most categories of transgender people as described above are not known for seeking the following treatments. Hormone replacement therapy for trans men induces beard growth and masculinizes skin, hair, voice, and fat distribution. Hormone replacement therapy for trans women feminizes fat distribution and breasts. Laser hair removal or electrolysis removes excess hair for trans women. Surgical procedures for trans women feminize the voice, skin, face, Adam's apple, breasts, waist, buttocks, and genitals. Surgical procedures for trans men masculinize the chest and genitals and remove the womb, ovaries, and fallopian tubes. The acronyms "GRS" and "SRS" refer to genital surgery. The term "sex reassignment therapy" (SRT) is used as an umbrella term for physical procedures required for transition. Use of the term "sex change" has been criticized for its emphasis on surgery, and the term "transition" is preferred.[6][100] Availability of these procedures depends on degree of gender dysphoria, presence or absence of gender identity disorder,[101] and standards of care in the relevant jurisdiction.

Trans men who have not had a hysterectomy and who take testosterone are at increased risk for endometrial cancer because androstenedione, which is made from testosterone in the body, can be converted into estrogen, and external estrogen is a risk factor for endometrial cancer.[102]

Law

Legal procedures exist in some jurisdictions which allow individuals to change their legal gender or name to reflect their gender identity. Requirements for these procedures vary from an explicit formal diagnosis of transsexualism, to a diagnosis of gender identity disorder, to a letter from a physician that attests the individual's gender transition or having established a different gender role.[103] In 1994, the DSM IV entry was changed from "Transsexual" to "Gender Identity Disorder". In many places, transgender people are not legally protected from discrimination in the workplace or in public accommodations.[20] A report released in February 2011 found that 90% of transgender people faced discrimination at work and were unemployed at double the rate of the general population,[18] and over half had been harassed or turned away when attempting to access public services.[18] Members of the transgender community also encounter high levels of discrimination in health care.[104]

Europe

36 countries in Europe require a mental health diagnosis for legal gender recognition and 20 countries still require sterilisation.[105] In April 2017, the European Court of Human Rights ruled that requiring sterilisation for legal gender recognition violates human rights.[106]

Denmark

Since 2014 it has been possible for adults without the requirement of a psychiatric evaluation, medical or surgical treatment, divorce or castration, to after a six-month ‘reflection period’ have their social security number changed and legally change gender.[107][108]

Germany

In November 2017, the Federal Constitutional Court ruled that the civil status law must allow a third gender option.[109] Thus officially recognising "third sex" meaning that birth certificates will not have blank gender entries for intersex people. The ruling came after an intersex person, who is neither a man nor woman according to chromosomal analysis, brought a legal challenge after attempting to change their registered sex to "inter" or divers.[110]

Canada

Jurisdiction over legal classification of sex in Canada is assigned to the provinces and territories. This includes legal change of gender classification. On June 19, 2017 Bill C-16, after having passed the legislative process in the House of Commons of Canada and the Senate of Canada, became law upon receiving Royal Assent which put it into immediate force.[111][112][113] The law updated the Canadian Human Rights Act and the Criminal Code to include "gender identity and gender expression" as protected grounds from discrimination, hate publications and advocating genocide. The bill also added "gender identity and expression" to the list of aggravating factors in sentencing, where the accused commits a criminal offence against an individual because of those personal characteristics. Similar transgender laws also exist in all the provinces and territories.

United States

In the United States, transgender people are protected from employment discrimination by Title VII of the Civil Rights Act of 1964. Exceptions apply to certain types of employers, for example, employers with fewer than 15 employees and religious organizations.[114] In 2020, the U.S. Supreme Court affirmed that Title VII prohibits discrimination against transgender people in the case R.G. & G.R. Harris Funeral Homes Inc. v. Equal Employment Opportunity Commission.[115]

Nicole Maines, a trans girl, took a case to Maine's Supreme Court in June, 2013. She argued that being denied access to her high school's women's restroom was a violation of Maine's Human Rights Act; one state judge has disagreed with her,[116] but Maines won her lawsuit against the Orono school district in January 2014 before the Maine Supreme Judicial Court.[117] On May 14, 2016, the United States Department of Education and Department of Justice issued guidance directing public schools to allow transgender students to use bathrooms that match their gender identities.[118]

On June 30, 2016, the United States Department of Defense removed the ban that prohibited transgender people from openly serving in the US military.[119] On July 27, 2017, President Donald Trump tweeted that transgender Americans will not be allowed to serve "in any capacity" in the United States Armed Forces.[120] Later that day, Joint Chiefs of Staff Chairman Joseph Dunford announced, "there will be no modifications to the current policy until the president’s direction has been received by the Secretary of Defense and the secretary has issued implementation guidance."[121]

In California, the School Success and Opportunity Act authored by Assemblyman Tom Ammiano, which became state law on January 1, 2014, says "A pupil shall be permitted to participate in sex-segregated school programs and activities, including athletic teams and competitions, and use facilities consistent with his or her gender identity, irrespective of the gender listed on the pupil's records."[122][123]

India

In April 2014, the Supreme Court of India declared transgender to be a 'third gender' in Indian law.[124][125][126] The transgender community in India (made up of Hijras and others) has a long history in India and in Hindu mythology.[127][128] Justice KS Radhakrishnan noted in his decision that, "Seldom, our society realizes or cares to realize the trauma, agony and pain which the members of Transgender community undergo, nor appreciates the innate feelings of the members of the Transgender community, especially of those whose mind and body disown their biological sex", adding:

Non-recognition of the identity of Hijras/transgender persons denies them equal protection of law, thereby leaving them extremely vulnerable to harassment, violence and sexual assault in public spaces, at home and in jail, also by the police. Sexual assault, including molestation, rape, forced anal and oral sex, gang rape and stripping is being committed with impunity and there are reliable statistics and materials to support such activities. Further, non-recognition of identity of Hijras/transgender persons results in them facing extreme discrimination in all spheres of society, especially in the field of employment, education, healthcare etc.[129]

Hijras face structural discrimination including not being able to obtain driving licenses, and being prohibited from accessing various social benefits. It is also common for them to be banished from communities.[130]

Religion

The Roman Catholic Church has been involved in the outreach to LGBT community for several years and continues doing so through Franciscan urban outreach centers, for example, the Open Hearts outreach in Hartford, Connecticut.[131]

Feminism

Some feminists and feminist groups are supportive of transgender people, but others are not. Though second-wave feminism argued for the sex and gender distinction, some feminists believed there was a conflict between transgender identity and the feminist cause; e.g., they believed that male-to-female transition abandoned or devalued female identity and that transgender people embraced traditional gender roles and stereotypes. Many transgender feminists, however, view themselves as contributing to feminism by questioning and subverting gender norms. Third-wave and contemporary feminism are generally more supportive of transgender people.[132]

Scientific studies of transsexuality

A study of Swedes estimated a ratio of 1.4:1 trans women to trans men for those requesting sex reassignment surgery and a ratio of 1:1 for those who proceeded.[133]

Twin studies suggest that there are likely genetic causes of transsexuality, although the precise genes involved are not fully understood.[134][135] One study published in the International Journal of Transgenderism found that 33% of identical twin pairs were both trans, compared to only 2.6% of non-identical twins who were raised in the same family at the same time, but were not genetically identical.[135]

Ray Blanchard created a taxonomy of male-to-female transsexualism that proposes two distinct etiologies for androphilic and gynephilic individuals that has become controversial, supported by J. Michael Bailey, Anne Lawrence, James Cantor and others, but opposed by Charles Allen Moser, Julia Serano, and the World Professional Association for Transgender Health.Population figures

Little is known about the prevalence of transgender people in the general population and reported prevalence estimates are greatly affected by variable definitions of transgender.[136] According to a recent systematic review, an estimated 9.2 out of every 100,000 people have received or requested gender affirmation surgery or transgender hormone therapy; 6.8 out of every 100,000 people have received a transgender-specific diagnoses; and 355 out of every 100,000 people self-identify as transgender.[136] These findings underscore the value of using consistent terminology related to studying the experience of transgender, as studies that explore surgical or hormonal gender affirmation therapy may or may not be connected with others that follow a diagnosis of “transsexualism,” “gender identity disorder,” or “gender dysphoria,” none of which may relate with those that assess self-reported identity.[136] Common terminology across studies does not yet exist, so population numbers may be inconsistent, depending on how they are being counted.

European Union

According to Amnesty International, 1.5 million transgender people live in the European Union, making up 0.3% of the population.[137]

UK

A 2011 survey conducted by the Equality and Human Rights Commission in the UK found that of 10,026 respondents, 1.4% would be classified into a gender minority group. The survey also showed that 1% had gone through any part of a gender reassignment process (including thoughts or actions).[138]

North America

Canada

The Trans PULSE survey conducted in 2009 and 2010 suggest that as many as 1 in 200 adults may be trans (transgender, transsexual, or transitioned) in the Canadian province of Ontario.[139] The 2017 survey of Canadian LGBT+ people called LGBT+ Realities Survey found that of the 1,897 respondents 11% identified as transgender (7% binary transgender, 4% non-binary transgender) and 1% identified as non-binary outside of the transgender umbrella.[140] The 2019 survey of the Two-Spirit and LGBTQ+ population in the Canadian city of Hamilton, Ontario called Mapping the Void: Two-Spirit and LGBTQ+ Experiences in Hamilton showed that 27.6% of the 906 respondents identified as transgender.[141]

United States

The Social Security Administration, since 1936, has tracked the sex of citizens.[142] Using this information, along with the Census data, Benjamin Cerf Harris tracked the prevalence of citizens changing to names associated with the opposite sex or changing sex marker. Harris found that such changes had occurred as early as 1936. He estimated that 89,667 individuals included in the 2010 Census had changed to an opposite-gendered name, 21,833 of whom had also changed sex marker.[142] Prevalence in the States varied, from 1.4 to 10.6 per 100,000.[142] While most people legally changed both name and sex, about a quarter of people changed name, and then five years later changed sex.[142] An earlier estimate in 1968, by Ira B. Pauly, estimated that about 2,500 transsexual people were living in the United States, with four times as many trans women as trans men.[143]

One effort to quantify the population in 2011 gave a "rough estimate" that 0.3% of adults in the US are transgender.[144][145] More recent studies released in 2016 estimate the proportion of Americans who identify as transgender at 0.5 to 0.6%. This would put the total number of transgender Americans at approximately 1.4 million adults (as of 2016).[146][147][148][149]

A survey by the Pew Research Center in 2017 found that American society is divided on "whether it's possible for someone to be a gender different from the sex they were assigned at birth."[150] It states, "Overall, roughly half of Americans (54%) say that whether someone is a man or a woman is determined by the sex they were assigned at birth, while 44% say someone can be a man or a woman even if that is different from the sex they were assigned at birth."[150]

Latin America

In Latin American cultures, a travesti is a person who has been assigned male at birth and who has a feminine, transfeminine, or "femme" gender identity. Travestis generally undergo hormonal treatment, use female gender expression including new names and pronouns from the masculine ones they were given when assigned a sex, and might use breast implants, but they are not offered or do not desire sex-reassignment surgery. Travesti might be regarded as a gender in itself (a "third gender"), a mix between man and woman ("intergender/androgynes"), or the presence of both masculine and feminine identities in a single person ("bigender"). They are framed as something entirely separate from transgender women, who possess the same gender identity of people assigned female at birth.

Other transgender identities are becoming more widely known, as a result of contact with other cultures of the Western world.[151] These newer identities, sometimes known under the umbrella use of the term "genderqueer",[151] along with the older travesti term, are known as non-binary and go along with binary transgender identities (those traditionally diagnosed under the now obsolete label of "transsexualism") under the single umbrella of transgender, but are distinguished from cross-dressers and drag queens and kings, that are held as nonconforming gender expressions rather than transgender gender identities when a distinction is made.[152]

Deviating from the societal standards for sexual behavior, sexual orientation/identity, gender identity, and gender expression have a single umbrella term that is known as sexodiverso or sexodiversa in both Spanish and Portuguese, with its most approximate translation to English being "queer".

Non-western cultures

Asia

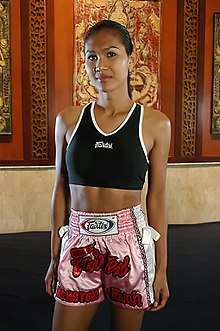

In Thailand and Laos,[153] the term kathoey is used to refer to male-to-female transgender people[154] and effeminate gay men.[155] Transgender people have also been documented in Iran,[156] Japan,[157] Nepal,[158] Indonesia,[159] Vietnam,[160] South Korea,[161] Singapore,[162] and the greater Chinese region, including Hong Kong,[163][164] Taiwan,[165] and the People's Republic of China.[166][167][168]

The cultures of the Indian subcontinent include a third gender, referred to as hijra in Hindi. In India, the Supreme Court on April 15, 2014, recognized a third gender that is neither male nor female, stating "Recognition of transgenders as a third gender is not a social or medical issue but a human rights issue."[169] In 1998, Shabnam Mausi became the first transgender person to be elected in India, in the central Indian state of Madhya Pradesh.[170]

North America

In what is now the United States and Canada, some Native American and First Nations cultures traditionally recognize the existence of more than two genders,[171] such as the Zuni male-bodied lhamana,[172] the Lakota male-bodied winkte,[173] and the Mohave male-bodied alyhaa and female-bodied hwamee.[174] These traditional people, along with those from other North American Indigenous cultures, are sometimes part of the contemporary, pan-Indian Two-Spirit community.[173] Historically, in most cultures who have alternate gender roles, if the spouse of a third gender person is not otherwise gender variant, they have not generally been regarded as other-gendered themselves, simply for being in a same-sex relationship.[174] In Mexico, the Zapotec culture includes a third gender in the form of the Muxe.[175]

Other

Among the ancient Middle Eastern Akkadian people, a salzikrum was a person who appeared biologically female but had distinct male traits. Salzikrum is a compound word meaning male daughter. According to the Code of Hammurabi, salzikrūm had inheritance rights like that of priestesses; they inherited from their fathers, unlike regular daughters. A salzikrum's father could also stipulate that she inherit a certain amount.[176] In Ancient Rome, the Gallae were castrated[177] followers of the Phrygian goddess Cybele and can be regarded as transgender in today's terms.[178][179]

In early Medina, gender-variant[180] male-to-female Islamic people were acknowledged[181] in the form of the Mukhannathun.

Mahu is a traditional third gender in Hawai'i and Tahiti. Mahu are valued as teachers, caretakers of culture, and healers, such as Kapaemahu. Also, in Fa'asamoa traditions, the Samoan culture allows a specific role for male to female transgender individuals as Fa'afafine.

Coming out

Transgender people vary greatly in choosing when, whether, and how to disclose their transgender status to family, close friends, and others. The prevalence of discrimination[182] and violence (transgender people are 28% more likely to be victims of violence)[183] against transgender persons can make coming out a risky decision. Fear of retaliatory behavior, such as being removed from the parental home while underage, is a cause for transgender people to not come out to their families until they have reached adulthood.[184] Parental confusion and lack of acceptance of a transgender child may result in parents treating a newly revealed gender identity as a "phase" or making efforts to change their children back to "normal" by utilizing mental health services to alter the child's gender identity.[185][186]

The internet can play a significant role in the coming out process for transgender people. Some come out in an online identity first, providing an opportunity to go through experiences virtually and safely before risking social sanctions in the real world.[187]

Media representation

As more transgender people are represented and included within the realm of mass culture, the stigma that is associated with being transgender can influence the decisions, ideas, and thoughts based upon it. Media representation, culture industry, and social marginalization all hint at popular culture standards and the applicability and significance to mass culture as well. These terms play an important role in the formation of notions for those who have little recognition or knowledge of transgender people. Media depictions represent only a minuscule spectrum of the transgender group,[188] which essentially conveys that those that are shown are the only interpretations and ideas society has of them.

However, in 2014, the United States reached a "transgender tipping point", according to Time.[189][190] At this time, the media visibility of transgender people reached a level higher than seen before. Since then, the number of transgender portrayals across TV platforms has stayed elevated.[191] Research has found that viewing multiple transgender TV characters and stories improves viewers' attitudes toward transgender people and related policies.[192]

Events

International Transgender Day of Visibility

International Transgender Day of Visibility is an annual holiday occurring on March 31[193][194] dedicated to celebrating transgender people and raising awareness of discrimination faced by transgender people worldwide. The holiday was founded by Michigan-based transgender activist[195] Rachel Crandall in 2009.[196]

Transgender Awareness Week

Transgender Awareness Week is a one-week celebration leading up to Transgender Day of Remembrance. The purpose of Transgender Awareness Week is to educate about transgender and gender non-conforming people and the issues associated with their transition or identity.[197]

Transgender Day of Remembrance

Transgender Day of Remembrance (TDOR) is held every year on November 20 in honor of Rita Hester, who was killed on November 28, 1998, in an anti-transgender hate crime. TDOR serves a number of purposes:

- it memorializes all of those who have been victims of hate crimes and prejudice,

- it raises awareness about hate crimes towards the transgender community,

- and it honors the dead and their relatives[198]

.jpg)

Trans March

Annual marches, protests or gatherings take place around the world for transgender issues, often taking place during the time of local Pride parades for LGBT people. These events are frequently organised by trans communities to build community, address human rights struggles, and create visibility.[199][200][201][202]

Pride symbols

A common symbol for the transgender community is the Transgender Pride Flag, which was designed by the American transgender woman Monica Helms in 1999, and was first shown at a pride parade in Phoenix, Arizona in 2000. The flag consists of five horizontal stripes: light blue, pink, white, pink, and light blue. Helms describes the meaning of the flag as follows:

The light blue is the traditional color for baby boys, pink is for girls, and the white in the middle is for "those who are transitioning, those who feel they have a neutral gender or no gender", and those who are intersex. The pattern is such that "no matter which way you fly it, it will always be correct. This symbolizes us trying to find correctness in our own lives."[203]

Other transgender symbols include the butterfly (symbolizing transformation or metamorphosis),[204] and a pink/light blue yin and yang symbol.[205] Several gender symbols have been used to represent transgender people, including ⚥ and ⚧.[206][207]

See also

- List of transgender and transsexual fictional characters

- List of transgender people

- List of transgender publications

- List of transgender-related topics

- List of transgender-rights organizations

- List of unlawfully killed transgender people

- Transgender history

- Transsexual pornography

Notes

-

- In April 1970, TV Guide published an article which referenced a post-operative transsexual movie character as being "transgendered."("Sunday Highlights". TV Guide. April 26, 1970. Archived from the original on 4 June 2012. Retrieved 28 May 2012.

[R]aquel Welch (left), moviedom's sex queen soon to be seen as the heroine/hero of Gore Vidal's transgendered "Myra Breckinridge"...

) - In the 1974 edition of Clinical Sexuality: A Manual for the Physician and the Professions, transgender was used as an umbrella term and the Conference Report from the 1974 "National TV.TS Conference" held in Leeds, West Yorkshire, UK used "trans-gender" and "trans.people" as umbrella terms.(Oliven, John F. (1974). Clinical sexuality: A Manual for the Physician and the Professions (3rd ed.). University of Michigan (digitized Aug 2008): Lippincott. pp. 110, 484–487. ISBN 978-0-397-50329-2. Archived from the original on 2015-12-05.

"Transgender deviance" p 110, "Transgender research" p 484, "transgender deviates" p 485, Transvestites not welcome at "Transgender Center" p 487

CS1 maint: location (link)), (2006). The Transgender Phenomenon (Elkins, Richard; King, Dave (2006). The Transgender Phenomenon. Sage. p. 13. ISBN 978-0-7619-7163-4. Archived from the original on 2015-09-26.) - However A Practical Handbook of Psychiatry (1974) references "transgender surgery" noting, "The transvestite rarely seeks transgender surgery, since the core of his perversion is an attempt to realize the fantasy of a phallic woman."(Novello, Joseph R. (1974). A Practical Handbook of Psychiatry. University of Michigan, digitized August 2008: C. C. Thomas. p. 176. ISBN 978-0-398-02868-8. Archived from the original on 2015-09-19.CS1 maint: location (link))

- In April 1970, TV Guide published an article which referenced a post-operative transsexual movie character as being "transgendered."("Sunday Highlights". TV Guide. April 26, 1970. Archived from the original on 4 June 2012. Retrieved 28 May 2012.

- Magnus Hirschfeld coined the German term Transsexualismus in 1923, which Cauldwell translated into English.

- The recurring concern that transsexual implies sexuality stems from the tendency of many informal speakers to ignore the sex and gender distinction and use gender for any male/female difference and sex for sexual activity. (Liberman, Mark. "Single-X Education". Language Log. Archived from the original on 15 April 2012. Retrieved 28 June 2012.)

References

- Altilio, Terry; Otis-Green, Shirley (2011). Oxford Textbook of Palliative Social Work. Oxford University Press. p. 380. ISBN 978-0199838271. Archived from the original on December 1, 2016. Retrieved April 12, 2016.

Transgender is an umbrella term for people whose gender identity and/or gender expression differs from the sex they were assigned at birth (Gay and Lesbian Alliance Against Defamation [GLAAD], 2007).

- Forsyth, Craig J.; Copes, Heith (2014). Encyclopedia of Social Deviance. Sage Publications. p. 740. ISBN 978-1483364698. Archived from the original on December 1, 2016. Retrieved April 12, 2016.

Transgender is an umbrella term for people whose gender identities, gender expressions, and/or behaviors are different from those culturally associated with the sex to which they were assigned at birth.

- Berg-Weger, Marla (2016). Social Work and Social Welfare: An Invitation. Routledge. p. 229. ISBN 978-1317592020. Archived from the original on December 1, 2016. Retrieved April 12, 2016.

Transgender: An umbrella term that describes people whose gender identity or gender expression differs from expectations associated with the sex assigned to them at birth.

- Thomas E. Bevan, The Psychobiology of Transsexualism and Transgenderism (2014, ISBN 1-4408-3127-0), page 42: "The term transsexual was introduced by Cauldwell (1949) and popularized by Harry Benjamin (1966) [...]. The term transgender was coined by John Oliven (1965) and popularized by various transgender people who pioneered the concept and practice of transgenderism. It is sometimes said that Virginia Prince (1976) popularized the term, but history shows that many transgender people advocated the use of this term much more than Prince."

- R Polly, J Nicole, Understanding the transsexual patient: culturally sensitive care in emergency nursing practice, in the Advanced Emergency Nursing Journal (2011): "The use of terminology by transsexual individuals to self-identify varies. As aforementioned, many transsexual individuals prefer the term transgender, or simply trans, as it is more inclusive and carries fewer stigmas. There are some transsexual individuals [,] however, who reject the term transgender; these individuals view transsexualism as a treatable congenital condition. Following medical and/or surgical transition, they live within the binary as either a man or a woman and may not disclose their transition history."

- Gay and Lesbian Alliance Against Defamation. "GLAAD Media Reference Guide – Transgender glossary of terms" Archived 2012-06-03 at WebCite, "GLAAD", USA, May 2010. Retrieved 2011-02-24. "An umbrella term for people whose gender identity and/or gender expression differs from what is typically associated with the sex they were assigned at birth."

- Bilodeau, Brent (2005). "Beyond the Gender Binary: A Case Study of Two Transgender Students at a Midwestern Research University". Journal of Gay & Lesbian Issues in Education. 3 (1): 29–44. doi:10.1300/J367v03n01_05. "Yet Jordan and Nick represent a segment of transgender communities that have largely been overlooked in transgender and student development research – individuals who express a non-binary construction of gender[.]"

- Susan Stryker, Stephen Whittle, The Transgender Studies Reader (ISBN 1-135-39884-4), page 666: "The authors note that, increasingly, in social science literature, the term "third gender" is being replaced by or conflated with the newer term "transgender."

- Joan C. Chrisler, Donald R. McCreary, Handbook of Gender Research in Psychology, volume 1 (2010, ISBN 1-4419-1465-X), page 486: "Transgender is a broad term characterized by a challenge of traditional gender roles and gender identity[. ...] For example, some cultures classify transgender individuals as a third gender, thereby treating this phenomenon as normative."

- Reisner, Sari L; Conron, Kerith; Scout, Nfn; Mimiaga, Matthew J; Haneuse, Sebastien; Austin, S. Bryn (2014). "Comparing In-Person and Online Survey Respondents in the U.S. National Transgender Discrimination Survey: Implications for Transgender Health Research". LGBT Health. 1 (2): 98–106. doi:10.1089/lgbt.2013.0018. PMID 26789619.

Transgender was defined broadly to cover those who transition from one gender to another as well as those who may not choose to socially, medically, or legally fully transition, including cross-dressers, people who consider themselves to be genderqueer, androgynous, and…

- "Sexual orientation, homosexuality and bisexuality". American Psychological Association. Archived from the original on August 8, 2013. Retrieved August 10, 2013.

- "Free & Equal Campaign Fact Sheet: Intersex" (PDF). United Nations Office of the High Commissioner for Human Rights. 2015. Archived (PDF) from the original on March 4, 2016. Retrieved March 28, 2016.

- "Definition of CISGENDER". www.merriam-webster.com. Archived from the original on 2019-03-26. Retrieved 2019-03-26.

- Kozee, H. B.; Tylka, T. L.; Bauerband, L. A. (2012). "Measuring transgender individuals' comfort with gender identity and appearance: Development and validation of the Transgender Congruence Scale". Psychology of Women Quarterly. 36 (2): 179–196. doi:10.1177/0361684312442161.

- Victoria Maizes, Integrative Women's Health (2015, ISBN 0190214805), page 745: "Many transgender people experience gender dysphoria—distress that results from the discordance of biological sex and experienced gender (American Psychiatric Association, 2013). Treatment for gender dysphoria, considered to be highly effective, includes physical, medical, and/or surgical treatments [...] some [transgender people] may not choose to transition at all."

- "Understanding Transgender People FAQ". National Center for Transgender Equality. 1 May 2009. Archived from the original on 22 April 2016. Retrieved 20 April 2016.

- Lombardi, Emilia L.; Anne Wilchins, Riki; Priesing, Dana; Malouf, Diana (October 2008). "Gender Violence: Transgender Experiences with Violence and Discrimination". Journal of Homosexuality. 42 (1): 89–101. doi:10.1300/J082v42n01_05. PMID 11991568.

- Gay and Lesbian Alliance Against Defamation. "Groundbreaking Report Reflects Persistent Discrimination Against Transgender Community" Archived 2011-08-03 at the Wayback Machine, GLAAD, USA, February 4, 2011. Retrieved 2011-02-24.

- Bradford, Judith; Reisner, Sari L.; Honnold, Julie A.; Xavier, Jessica (2013). "Experiences of Transgender-Related Discrimination and Implications for Health: Results From the Virginia Transgender Health Initiative Study". American Journal of Public Health. 103 (10): 1820–1829. doi:10.2105/AJPH.2012.300796. PMC 3780721. PMID 23153142.

- Whittle, Stephen. "Respect and Equality: Transsexual and Transgender Rights." Routledge-Cavendish, 2002.

- Oliven, John F. (1965). Sexual hygiene and pathology: a manual for the physician and the professions. Lippincott.

- Oliven, John F. (1965). "Sexual Hygiene and Pathology". The American Journal of the Medical Sciences. 250 (2): 235. doi:10.1097/00000441-196508000-00054.: "Where the compulsive urge reaches beyond female vestments, and becomes an urge for gender ("sex") change, transvestism becomes "transsexualism." The term is misleading; actually, "transgenderism" is what is meant, because sexuality is not a major factor in primary transvestism. Psychologically, the transsexual often differs from the simple cross-dresser; he is conscious at all times of a strong desire to be a woman, and the urge can be truly consuming.", p. 514

- Rawson, K. J.; Williams, Cristan (2014). "Transgender: The Rhetorical Landscape of a term". Present Tense: A Journal of Rhetoric in Society. 3 (2). Archived from the original on 2017-05-15. Retrieved 2017-05-18.

- Elkins, Richard; King, Dave (2006). The Transgender Phenomenon. Sage. pp. 13–14. ISBN 978-0-7619-7163-4. Archived from the original on 2015-09-26.

- Stryker, S. (2004), "... lived full-time in a social role not typically associated with their natal sex, but who did not resort to genital surgery as a means of supporting their gender presentation ..." in Transgender Archived 2006-03-21 at the Wayback Machine from the GLBTQ: an encyclopedia of gay, lesbian, bisexual, transgender and queer culture. Retrieved 2007-04-10.

- The Radio Times (1979: 2 June)

- Peo, TV-TS Tapestry Board of Advisors, Roger E. (1984). "The 'Origins' and 'Cures' for Transgender Behavior". The TV-TS Tapestry (2). Archived from the original on 7 April 2012. Retrieved 28 May 2012.

- "First International Conference on Transgender Law and Employment Policy (1992)". organizational pamphlet. ICTLEP/. 1992. Archived from the original on 30 March 2012. Retrieved 28 May 2012.

Transgendered persons include transsexuals, transgenderists, and other crossdressers of both sexes, transitioning in either direction (male to female or female to male), of any sexual orientation, and of all races, creeds, religions, ages, and degrees of physical impediment.

- Stryker, Susan. "Transgender History, Homonormativity, and Disciplinarity". Radical History Review, Vol. 2008, No. 100. (Winter 2008), pp. 145–157

- Myers, Alex (14 May 2018). "Trans Terminology Seems Like It's Changing All the Time. And That's a Good Thing". Slate Magazine. Archived from the original on 15 May 2018. Retrieved 15 May 2018.

- Glicksman, Eve (April 2013). "Transgender terminology: It's complicated". Vol 44, No. 4: American Psychological Association. p. 39. Archived from the original on 2013-09-25. Retrieved 2013-09-17.

Use whatever name and gender pronoun the person prefers

CS1 maint: location (link) - "Meeting the Health Care Needs of Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, and Transgender (LGBT) People: The End to LGBT Invisibility" (PowerPoint Presentation). The Fenway Institute. p. 24. Archived from the original on 2013-10-20. Retrieved 2013-09-17.

Use the pronoun that matches the person's gender identity

- Gay and Lesbian Alliance Against Defamation. "GLAAD's Transgender Resource Page" Archived 2012-10-06 at the Wayback Machine, "GLAAD", USA. Retrieved 2011-02-24. "Problematic: "transgendered". Preferred: transgender. The adjective transgender should never have an extraneous "-ed" tacked onto the end. An "-ed" suffix adds unnecessary length to the word and can cause tense confusion and grammatical errors. It also brings transgender into alignment with lesbian, gay, and bisexual. You would not say that Elton John is "gayed" or Ellen DeGeneres is "lesbianed," therefore you would not say Chaz Bono is "transgendered."

- Dan Savage, Savage Love: Gayed, Blacked, Transgendered (Creative Loafing, 11 January 2014) Archived 25 January 2016 at the Wayback Machine

- Guardian and Observer style guide Archived 2017-07-09 at the Wayback Machine: use transgender [...] only as an adjective: transgender person, trans person; never "transgendered person" or "a transgender"

- Martin, Katherine. "New words notes June 2015". Oxford English Dictionary. Oxford University Press. Archived from the original on 14 August 2015. Retrieved 2 August 2015.

- Transgender Rights (2006, ISBN 0-8166-4312-1), edited by Paisley Currah, Richard M. Juang, Shannon Minter

- A. C. Alegria, Transgender identity and health care: Implications for psychosocial and physical evaluation, in the Journal of the American Academy of Nurse Practitioners, volume 23, issue 4 (2011), pages 175–182: "Transgender, Umbrella term for persons who do not conform to gender norms in their identity and/or behavior (Meyerowitz, 2002). Transsexual, Subset of transgenderism; persons who feel discordance between natal sex and identity (Meyerowitz, 2002)."

- For example, Virginia Prince used transgender to distinguish cross-dressers from transsexual people ("glbtq > social sciences >> Prince, Virginia Charles". glbtq.com. Archived from the original on 2015-02-11.), writing in Men Who Choose to Be Women (in Sexology, February 1969) that "I, at least, know the difference between sex and gender and have simply elected to change the latter and not the former."

- "Sex -- Medical Definition". medilexicon.com. Archived from the original on 2014-02-22.: defines sex as a biological or physiological quality, while gender is a (psychological) "category to which an individual is assigned by self or others...".

- UNCW: Developing and Implementing a Scale to Assess Attitudes Regarding Transsexuality Archived 2014-02-21 at the Wayback Machine

- A Swenson, Medical Care of the Transgender Patient, in Family Medicine (2014): "While some transsexual people still prefer to use the term to describe themselves, many transgender people prefer the term transgender to transsexual."

- "GLAAD Media Reference Guide". 2011-09-09. Archived from the original on 2012-06-03. Retrieved 2013-12-27.

- Parker, Jerry (October 18, 1979). "Christine Recalls Life as Boy from the Bronx". Newsday/Winnipeg Free Press. Archived from the original on 25 April 2012. Retrieved 28 May 2012.

If you understand trans-genders," she says, (the word she prefers to transsexuals), "then you understand that gender doesn’t have to do with bed partners, it has to do with identity.

- "News From California: 'Transgender'". Appeal-Democrat/Associate Press. May 11, 1982. pp. A–10. Archived from the original on 12 April 2012. Retrieved 28 May 2012.

she describes people who have had such operations’ "transgender" rather than transsexual. "Sexuality is who you sleep with, but gender is who you are," she explained

- "Fenway Health Glossary of Gender and Transgender Terms" (PDF). January 2010. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2013-10-19. Retrieved 2013-12-27.

- Valentine, David. Imagining Transgender: An Ethnography of a Category, Duke University, 2007

- Stryker, Susan. Introduction. In Stryker and S. Whittle (Eds.), The Transgender Studies Reader, New York: Routledge, 2006. 1–17

- Kelley Winters, "Gender Madness in American Psychiatry, essays from the struggle for dignity, 2008, p. 198. "Some Transsexual individuals also identify with the broader transgender community; others do not."

- Boyd, Hellen (2008-07-27). "The Umbrella". enGender. Archived from the original on 22 July 2012. Retrieved 28 June 2012.

the only part of the gender binary we *necessarily* challenge is the notion that people are always assigned to the right side of the binary at birth, and don’t need sympathy or help if the assignment goes wrong.

- Benjamin, H. (1966). The transsexual phenomenon. New York: Julian Press, page 23.

- Ekins, Richard (2005). Science, politics and clinical intervention: Harry Benjamin, transsexualism and the problem of heteronormativity Sexualities July 2005 vol. 8 no. 3 306-328 doi: 10.1177/1363460705049578

- Hansbury, Griffin (2008). The Middle Men: An Introduction to the Transmasculine Identities. Studies in Gender and Sexuality Volume 6, Issue 3, 2005 doi:10.1080/15240650609349276

- Amy McCrea, Under the Transgender Umbrella: Improving ENDA's Protections, in the Georgetown Journal of Gender and the Law (2013): "This article will begin by providing a background on transgender people, highlighting the experience of a subset of non-binary individuals, bigender people, ..."

- Wilchins, Riki Anne (2002) 'It's Your Gender, Stupid’, pp.23–32 in Joan Nestle, Clare Howell and Riki Wilchins (eds.) Genderqueer: Voices from Beyond the Sexual Binary. Los Angeles:Alyson Publications, 2002.

- Nestle, J. (2002) "...pluralistic challenges to the male/female, woman/man, gay/straight, butch/femme constructions and identities..." from Genders on My Mind, pp.3–10 in Genderqueer: Voices from Beyond the Sexual Binary, edited by Joan Nestle, Clare Howell and Riki Wilchins, published by Los Angeles:Alyson Publications, 2002:9. Retrieved 2007-04-07.

- Lindqvist, Anna (18 Feb 2020). "What is gender, anyway: a review of the options for operationalising gender". Taylor & Francis Online. Retrieved 11 June 2020.

- "Androgyne – Define Androgyne at Dictionary.com". Dictionary.com. Archived from the original on 2008-04-13.

- "Sexual Orientation and Gender Identity Definitions". Retrieved 2020-07-10.

- "WHAT'S THE DIFFERENCE BETWEEN GENDER IDENTITY AND SEXUAL ORIENTATION?". Retrieved 2020-07-10.

- E. D. Hirsch, Jr., E.D., Kett, J.F., Trefil, J. (2002) "Transvestite: Someone who dresses in the clothes usually worn by the opposite sex." in Definition of the word "transvestite" Archived 2007-10-12 at the Wayback Machine from The New Dictionary of Cultural Literacy, Third Edition Archived August 18, 2007, at the Wayback Machine. Retrieved 2007-08-13.

- various (2006) "trans·ves·tite... (plural trans·ves·tites), noun. Definition: somebody who dresses like opposite sex:" in Definition of the word "transvestite" Archived 2007-11-09 at the Wayback Machine from the Encarta World English Dictionary (North American Edition) Archived 2009-10-31 at WebCite. Retrieved 2007-08-13.

- Raj, R (2002) "transvestite (TV): n. Synonym: crossdresser (CD):" in Towards a Transpositive Therapeutic Model: Developing Clinical Sensitivity and Cultural Competence in the Effective Support of Transsexual and Transgendered Clients from the International Journal of Transgenderism 6,2. Retrieved 2007-08-13. Archived September 27, 2007, at the Wayback Machine

- Hall, B. et al. (2007) "...Many say this term (crossdresser) is preferable to transvestite, which means the same thing..." and "...transvestite (TV) – same as cross-dresser. Most feel cross-dresser is the preferred term..." in Discussion Paper: Toward a Commission Policy on Gender Identity Archived 2007-09-27 at the Wayback Machine from the Ontario Human Rights Commission Archived 2007-08-13 at the Wayback Machine. Retrieved 2007-08-13.

- Green, E., Peterson, E.N. (2006) "...The preferred term is 'cross-dresser', but the term 'transvestite' is still used in a positive sense in England..." in LGBTTSQI Terminology Archived 2013-09-05 at the Wayback Machine from Trans-Academics.org Archived 2007-04-24 at the Wayback Machine. Retrieved 2007-08-13.

- Gilbert, Michael A. (2000). "The Transgendered Philosopher". International Journal of Transgenderism. Archived from the original on January 26, 2016. Retrieved December 16, 2015.

- Gilbert, Michael ‘Miqqi Alicia’ (2000) "The Transgendered Philosopher" in Special Issue on What is Transgender? Archived 2007-10-11 at the Wayback Machine from The International Journal of Transgenderism, Special Issue July 2000 Archived 2007-10-11 at the Wayback Machine. Retrieved 2007-10-09.

- Docter, Richard F.; Prince, Virginia (1997). "Transvestism: A survey of 1032 cross-dressers". Archives of Sexual Behavior. 26 (6): 589–605. doi:10.1023/a:1024572209266. PMID 9415796.

- World Health Organisation (1992) "...Fetishistic transvestism is distinguished from transsexual transvestism by its clear association with sexual arousal and the strong desire to remove the clothing once orgasm occurs and sexual arousal declines...." in ICD-10, Gender Identity Disorder, category F65.1 Archived 2009-04-22 at the Wayback Machine published by the World Health Organisation Archived 2016-07-05 at the Wayback Machine. Retrieved 2007-08-13.

- APA task force (1994) "...The paraphiliac focus of Transvestic Fetishism involves cross-dressing. Usually the male with Transvestic Fetishism keeps a collection of female clothes that he intermittently uses to cross-dress. While cross dressed, he usually masturbates..." in DSM-IV: Sections 302.3 Archived 2007-02-11 at the Wayback Machine published by the American Psychiatric Association. Retrieved 2007-08-13.

- "The Many Styles Of Drag Kings, Photographed In And Out Of Drag". HuffPost. 2019-11-12. Retrieved 2020-06-03.

- "How Drag Queens Work". HowStuffWorks. 2012-11-12. Retrieved 2020-06-03.

- Answers to Your Questions About Transgender Individuals and Gender Identity Archived 2010-06-15 at the Wayback Machine report from the website of the American Psychological Association - "What is the relationship between transgender and sexual orientation?"

- Tobin, H.J. (2003) "...It has become more and more clear that trans people come in more or less the same variety of sexual orientations as non-trans people..." Sexual Orientation from Sexuality in Transsexual and Transgender Individuals.

- Blanchard, R. (1989) The classification and labeling of nonhomosexual gender dysphorias from Archives of Sexual Behavior, Volume 18, Number 4, August 1989. Retrieved via SpringerLink Archived 2012-01-22 at the Wayback Machine on 2007-04-06.

- APA task force (1994) "...For sexually mature individuals, the following specifiers may be noted based on the individual's sexual orientation: Sexually Attracted to Males, Sexually Attracted to Females, Sexually Attracted to Both, and Sexually Attracted to Neither..." in DSM-IV: Sections 302.6 and 302.85 Archived 2007-02-11 at the Wayback Machine published by the American Psychiatric Association. Retrieved via Mental Health Matters Archived 2007-04-07 at the Wayback Machine on 2007-04-06.

- Goethals, S.C. and Schwiebert, V.L. (2005) "...counselors to rethink their assumptions regarding gender, sexuality and sexual orientation. In addition, they supported counselors' need to adopt a transpositive disposition to counseling and to actively advocate for transgendered persons..." Counseling as a Critique of Gender: On the Ethics of Counseling Transgendered Clients from the International Journal for the Advancement of Counselling, Vol. 27, No. 3, September 2005. Retrieved via SpringerLink Archived 2012-01-22 at the Wayback Machine on 2007-04-06.

- Retro Report (2015-06-15). "Transforming History". Retro Report. Retro Report. Archived from the original on 10 July 2015. Retrieved 15 July 2015.

- "The Report of the 2015 U.S. Transgender Survey" (PDF). National Center for Transgender Equality. Archived (PDF) from the original on 9 December 2016. Retrieved 6 March 2016.

- "Trans PULSE Canada Report No. 1 or 10". 10 March 2020. Retrieved 10 March 2020.

- Brown, M.L. & Rounsley, C.A. (1996) True Selves: Understanding Transsexualism – For Families, Friends, Coworkers, and Helping Professionals Jossey-Bass: San Francisco ISBN 0-7879-6702-5

- Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fourth Edition (1994)

- Atwill, Nicole (2010-02-17). "France: Gender Identity Disorder Dropped from List of Mental Illnesses | Global Legal Monitor". www.loc.gov. Archived from the original on 2017-05-11. Retrieved 2017-10-18.

- "La transsexualité ne sera plus classée comme affectation psychiatrique". Le Monde. May 16, 2009. Archived from the original on February 26, 2018. Retrieved March 14, 2018.

- "La France est très en retard dans la prise en charge des transsexuels". Libération (in French). 2011-05-17. Archived from the original on 2014-11-30.

En réalité, ce décret n'a été rien d'autre qu'un coup médiatique, un très bel effet d'annonce. Sur le terrain, rien n'a changé.

- Garloch, Karen (9 May 2016). "What it means to be transgender: Answers to 5 key questions". Charlotte Observer. Archived from the original on 20 December 2016. Retrieved 18 December 2016.

- Answers to Your Questions About Transgender Individuals and Gender Identity Archived 2010-06-15 at the Wayback Machine report from the website of the American Psychological Association - "Is being transgender a mental disorder?"

- Carroll, L.; Gilroy, P.J.; Ryan, J. (2002). "Transgender issues in counselor education". Counselor Education and Supervision. 41 (3): 233–242. doi:10.1002/j.1556-6978.2002.tb01286.x.

- Benson, Kristen E (2013). "Seeking support: Transgender client experiences with mental health services". Journal of Feminist Family Therapy. 25 (1): 17–40. doi:10.1080/08952833.2013.755081.

- "Standards of care for the health of transsexual, transgender, and gender nonconforming people—7th version" (PDF). The World Professional Association for Transgender Health. Archived from the original (PDF) on 3 March 2012. Retrieved 30 November 2014.

- Shute, Joe (2 October 2017). "The new taboo: More people regret sex change and want to 'detransition', surgeon says". National Post. Postmedia. Retrieved 2 October 2017.

Dr. Miroslav Djordjevic says more people, particularly transgender women over 30, are asking for reversal surgery, yet their regrets remain taboo.

- Hanssmann, C.; Morrison, D.; Russian, E. (2008). "Talking, gawking, or getting it done: Providing trainings to increase cultural and clinical competence for transgender and gender-nonconforming patients and clients". Sexuality Research and Social Policy. 5: 5–23. doi:10.1525/srsp.2008.5.1.5.

- Newsroom | APA DSM-5 Archived 2008-09-27 at the Wayback Machine

- Gender Identity Disorder Reform Archived 2008-09-06 at the Wayback Machine

- "France: Transsexualism will no longer be classified as a mental illness in France". ilga.org. Archived from the original on 2013-09-10.

- "Le transsexualisme n'est plus une maladie mentale en France" [Transsexualism is no longer a mental illness in France]. Le Monde.fr (in French). December 2, 2010. Archived from the original on February 13, 2010. Retrieved February 12, 2010.

- Haas, Ann P.; Rodgers, Philip L.; Herman, Jody L. (January 2014). Suicide Attempts among Transgender and Gender Non-Conforming Adults: Findings of the National Transgender Discrimination Survey (PDF). American Foundation for Suicide Prevention and the Williams Institute on Sexual Orientation and Gender Identity Law and Public Policy. pp. 2–3, 11. Archived from the original (PDF) on October 8, 2017. Retrieved October 9, 2017.

- Herman, Jody L.; Brown, Taylor N.T.; Haas, Ann P. (September 2019). "Suicide Thoughts and Attempts Among Transgender Adults" (PDF). Williams Institute on Sexual Orientation and Gender Identity Law and Public Policy. Archived from the original (PDF) on May 13, 2020. Retrieved May 13, 2020.

- Urquhart, Evan (March 21, 2018). "A Disproportionate Number of Autistic Youth Are Transgender. Why?". Slate. Archived from the original on March 21, 2018. Retrieved January 10, 2018.

- Pfäfflin F., Junge A. (1998) "...This critique for the use of the term sex change in connection to sex reassignment surgery stems from the concern about the patient, to take the patient seriously...." in Sex Reassignment: Thirty Years of International Follow-Up Studies: A Comprehensive Review, 1961–1991 from the Electronic Book Collection of the International Journal of Transgenderism. Retrieved 2007-09-06.

- APA task force (1994) "...preoccupation with getting rid of primary and secondary sex characteristics..." in DSM-IV: Sections 302.6 and 302.85 Archived 2007-02-11 at the Wayback Machine published by the American Psychiatric Association. Retrieved via Mental Health Matters Archived 2007-04-07 at the Wayback Machine on 2007-04-06.

- Committee on Health Care for Underserved Women (2011). "Committee Opinion No. 512". Obstetrics & Gynecology. 118 (6): 1454–8. doi:10.1097/AOG.0b013e31823ed1c1. PMID 22105293.

- Currah, Paisley; M. Juang, Richard; Minter, Shannon Price, eds. (2006). Transgender Rights. Minnesota University Press. pp. 51–73. ISBN 978-0-8166-4312-7.

- Gay and Lesbian Alliance Against Defamation. "IN THE LIFE Follows LGBT Seniors as They Face Inequality in Healthcare" Archived 2011-08-04 at the Wayback Machine, "GLAAD", USA, November 3, 2010. Retrieved 2011-02-24.

- "– Trans Rights Europe Map & Index 2017". tgeu.org. Archived from the original on 2017-10-19. Retrieved 2017-10-18.

- "HUDOC - European Court of Human Rights". hudoc.echr.coe.int. Archived from the original on 2017-10-19. Retrieved 2017-10-18.

- "www.cpr.dk". www.cpr.dk. Archived from the original on 2017-10-19. Retrieved 2017-10-18.

- "English translation of the laws regarding the Danish social security system (CPR)" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 2017-10-19.

- "Bundesverfassungsgericht - Press - Civil status law must allow a third gender option". www.bundesverfassungsgericht.de. Archived from the original on 2017-11-15. Retrieved 2017-12-18.

- "Germany's top court just officially recognised a third sex". The Independent. 2017-11-08. Archived from the original on 2017-12-04. Retrieved 2017-12-18.

- LegisInfo (42nd Parliament, 1st Session). Archived 2016-05-22 at the Wayback Machine

- LEGISinfo - House Government Bill C-16 (42-1) Archived 2016-12-24 at the Wayback Machine

- Tasker, John Paul (June 16, 2017). "Canada enacts protections for transgender community". CBC News. Archived from the original on June 17, 2017. Retrieved June 16, 2017.

- "Civil Rights Act of 1964 – CRA – Title VII – Equal Employment Opportunities – 42 US Code Chapter 21". finduslaw. Archived from the original on October 21, 2010. Retrieved June 6, 2010.

- Neidig, Harper (June 15, 2020). "Workers can't be fired for being gay or transgender, Supreme Court rules". The Hill. Retrieved June 15, 2020.

- June, Daniel (13 June 2013). "Transgender Girl in Maine Seeks Supreme Court's Approval to Use School's Girls Room". JD Journal. Archived from the original on 15 June 2013. Retrieved 13 June 2013.

- Sharp, David (January 31, 2014). "Maine Court Rules In Favor Of Transgender Pupil". The Huffington Post. Archived from the original on December 12, 2015. Retrieved December 16, 2015.

- Grinberg, Emanuella (May 14, 2016). "Feds issue guidance on transgender access to school bathrooms". CNN. Archived from the original on May 18, 2016. Retrieved May 19, 2016.

- "Transgender Service Members Can Now Serve Openly, Carter Announces". June 30, 2016. Archived from the original on August 10, 2017. Retrieved August 9, 2017.