LGBT culture in New York City

New York City has one of the largest LGBTQ populations in the world and the most prominent. Brian Silverman, the author of Frommer's New York City from $90 a Day, wrote the city has "one of the world's largest, loudest, and most powerful LGBT communities", and "Gay and lesbian culture is as much a part of New York's basic identity as yellow cabs, high-rise buildings, and Broadway theatre".[4] LGBT Americans in New York City constitute by significant margins the largest self-identifying lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender communities in the United States, and the 1969 Stonewall riots in Greenwich Village are widely considered to be the genesis of the modern gay rights movement.[5] As of 2005, New York City was home to an estimated 272,493 self-identifying gay and bisexual individuals.[6] The New York metropolitan area had an estimated 568,903 self-identifying GLB residents.[6] Meanwhile, New York City is also home to the largest transgender population in the United States, estimated at 50,000 in 2018, concentrated in Manhattan and Queens.[7]

| Part of a series on |

| LGBT topics |

|---|

| lesbian ∙ gay ∙ bisexual ∙ transgender |

|

Issues

|

|

Academic fields and discourse |

|

|

History as gay metropolis

Charles Kaiser, author of The Gay Metropolis: The Landmark History of Gay Life in America, wrote that in the era after World War II, "New York City became the literal gay metropolis for hundreds of thousands of immigrants from both within and without the United States: the place they chose to learn how to live openly, honestly and without shame."[8]

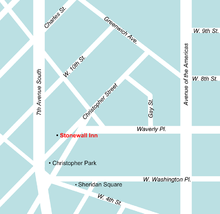

Stonewall Inn

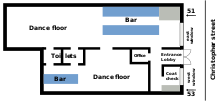

The Stonewall Inn, located at 51 and 53 Christopher Street, along with several other establishments in the city, was owned by the Genovese crime family.[9] In 1966, three members of the Mafia invested $3,500 to turn the Stonewall Inn into a gay bar, after it had been a restaurant and a nightclub for heterosexuals. Once a week a police officer would collect envelopes of cash as a payoff; the Stonewall Inn had no liquor license.[10][11] It had no running water behind the bar—used glasses were run through tubs of water and immediately reused.[12] There were no fire exits, and the toilets overran consistently.[13] Though the bar was not used for prostitution, drug sales and other "cash transactions" took place. It was the only bar for gay men in New York City where dancing was allowed;[14] dancing was its main draw since its re-opening as a gay club.[15]

Visitors to the Stonewall Inn in 1969 were greeted by a bouncer who inspected them through a peephole in the door. The legal drinking age was 18, and to avoid unwittingly letting in undercover police (who were called "Lily Law", "Alice Blue Gown", or "Betty Badge"[16]), visitors would have to be known by the doorman, or look gay. The entrance fee on weekends was $3, for which the customer received two tickets that could be exchanged for two drinks. Patrons were required to sign their names in a book to prove that the bar was a private "bottle club", but rarely signed their real names. There were two dance floors in the Stonewall; the interior was painted black, making it very dark inside, with pulsing gel lights or black lights. If police were spotted, regular white lights were turned on, signaling that everyone should stop dancing or touching.[16] In the rear of the bar was a smaller room frequented by "queens"; it was one of two bars where effeminate men who wore makeup and teased their hair (though dressed in men's clothing) could go.[17] Only a few transvestites, or men in full drag, were allowed in by the bouncers. The customers were "98 percent male" but a few lesbians sometimes came to the bar. Younger homeless adolescent males, who slept in nearby Christopher Park, would often try to get in so customers would buy them drinks.[18] The age of the clientele ranged between the upper teens and early thirties, and the racial mix was evenly distributed among white, Black, and Hispanic patrons.[17][19] Because of its even mix of people, its location, and the attraction of dancing, the Stonewall Inn was known by many as "the gay bar in the city".[20]

Police raids on gay bars were frequent, occurring on average once a month for each bar. Many bars kept extra liquor in a secret panel behind the bar, or in a car down the block, to facilitate resuming business as quickly as possible if alcohol was seized.[9] Bar management usually knew about raids beforehand due to police tip-offs, and raids occurred early enough in the evening that business could commence after the police had finished.[21] During a typical raid, the lights were turned on, and customers were lined up and their identification cards checked. Those without identification or dressed in full drag were arrested; others were allowed to leave. Some of the men, including those in drag, used their draft cards as identification. Women were required to wear three pieces of feminine clothing, and would be arrested if found not wearing them. Employees and management of the bars were also typically arrested.[21] The period immediately before June 28, 1969, was marked by frequent raids of local bars—including a raid at the Stonewall Inn on the Tuesday before the riots[22]—and the closing of the Checkerboard, the Tele-Star, and two other clubs in Greenwich Village.[23]

On June 23, 2015, the Stonewall Inn was the first landmark in New York City to be recognized by the New York City Landmarks Preservation Commission on the basis of its status in LGBT history,[24] and on June 24, 2016, the Stonewall National Monument was named the first U.S. National Monument dedicated to the LGBTQ-rights movement.[5]

Stonewall riots

Police raid

At 1:20 a.m. on Saturday, June 28, 1969, four plainclothes policemen in dark suits, two patrol officers in uniform, and Detective Charles Smythe and Deputy Inspector Seymour Pine arrived at the Stonewall Inn's double doors and announced "Police! We're taking the place!"[26] Stonewall employees do not recall being tipped off that a raid was to occur that night, as was the custom. According to Duberman (p. 194), there was a rumor that one might happen, but since it was much later than raids generally took place, Stonewall management thought the tip was inaccurate. Days after the raid, one of the bar owners complained that the tipoff had never come, and that the raid was ordered by the Bureau of Alcohol, Tobacco, and Firearms, who objected that there were no stamps on the liquor bottles, indicating the alcohol was bootlegged.

Historian David Carter presents information[27] indicating that the Mafia owners of the Stonewall and the manager were blackmailing wealthier customers, particularly those who worked in Lower Manhattan's Financial District. They appeared to be making more money from extortion than they were from liquor sales in the bar. Carter deduces that when the police were unable to receive kickbacks from blackmail and the theft of negotiable bonds (facilitated by pressuring gay Wall Street customers), they decided to close the Stonewall Inn permanently. Two undercover policewomen and two undercover policemen had entered the bar earlier that evening to gather visual evidence, as the Public Morals Squad waited outside for the signal. Once inside, they called for backup from the Sixth Precinct using the bar's pay telephone. The music was turned off and the main lights were turned on. Approximately 205 people were in the bar that night. Patrons who had never experienced a police raid were confused. A few who realized what was happening began to run for doors and windows in the bathrooms, but police barred the doors. As Michael Fader remembered,

Things happened so fast you kind of got caught not knowing. All of a sudden there were police there and we were told to all get in lines and to have our identification ready to be led out of the bar.

The raid did not go as planned. Standard procedure was to line up the patrons, check their identification, and have female police officers take customers dressed as women to the bathroom to verify their gender, upon which any men dressed as women would be arrested. Those dressed as women that night refused to go with the officers. Men in line began to refuse to produce their identification. The police decided to take everyone present to the police station, after separating those cross-dressing in a room in the back of the bar. Maria Ritter, then known as Steve to her family, recalled, "My biggest fear was that I would get arrested. My second biggest fear was that my picture would be in a newspaper or on a television report in my mother's dress!"[28] Both patrons and police recalled that a sense of discomfort spread very quickly, spurred by police who began to assault some of the lesbians by "feeling some of them up inappropriately" while frisking them.[29]

Transgender contribution

Despite playing a significant role in fighting for LGBT equality during the period of the Stonewall Riots and thereafter[30] the transgender community in New York City had previously felt marginalized and neglected by the gay community.[30] Since then, and especially during the 21st century, New York City's transgender community has grown in size and prominence,[31] reaching an estimated 50,000 in 2018.[7] Brooklyn Liberation March, the largest transgender rights demonstration in LGBTQ history, took place on June 14, 2020 stretching from Grand Army Plaza to Fort Greene, Brooklyn, focused on supporting Black transgender lives.[32][33]

State of New York official LGBT monument

On June 25, 2017, the day of 2017 New York City Pride March festivities, New York Governor Andrew Cuomo announced that the artist Anthony Goicolea had been chosen to design the first official monument to LGBT individuals commissioned by the State of New York – in contrast to the Stonewall National Monument, which was commissioned by the U.S. federal government. The State monument is planned to be built in Hudson River Park in Manhattan, near the waterfront Hudson River piers which have served as historically significant symbols of New York's role as a meeting place and a safe haven for LGBT communities.[34]

Demographics and economy

Population and concentration

New York City has been estimated to have become home to over 270,000 self-identifying gay and bisexual individuals,[6] higher than San Francisco and Los Angeles combined.

| Geographic entity | GLB population | Density of GLB individuals per square mile | Percentage of GLB individuals in population |

|---|---|---|---|

| New York City | 272,493 | 894 | 4.5 (2005) |

| New York City metropolitan area | 568,903 | 84.7 | 4.0 |

Economic clout

Lonely Planet New York City stated that of the demographics, the city's LGBT population has "one of the largest disposable incomes",[35] encompassing professionals including physicians, attorneys, engineers, scientists, financiers, and journalists, as well as those in the entertainment industry, fashion design, and realty. Conversely, New York City is also a highly popular LGBT tourist destination,[36] and the city actively courts LGBTQ tourism.[37]

Gay villages

Manhattan

Chelsea in Manhattan has become a focal point of gay socialization. The Christopher Street area of the West Village portion of Greenwich Village in Manhattan was the historical hub of gay life in New York City and continues to be a cultural center for the LGBT experience. The East Village/Lower East Side area of Manhattan is also a gayborhood.[38] Hell's Kitchen and Morningside Heights are additional Manhattan neighborhoods which have developed a significant LGBT presence of their own.[36]

Greenwich Village

The Manhattan neighborhoods of Greenwich Village and Harlem were home to a sizable homosexual population after World War I, when men and women who had served in the military took advantage of the opportunity to settle in larger cities. The enclaves of gays and lesbians, described by a newspaper story as "short-haired women and long-haired men", developed a distinct subculture through the following two decades.[39] Prohibition inadvertently benefited gay establishments, as drinking alcohol was pushed underground along with other behaviors considered immoral. New York City passed laws against homosexuality in public and private businesses, but because alcohol was in high demand, speakeasies and impromptu drinking establishments were so numerous and temporary that authorities were unable to police them all.[40] However, police raids happened, resulting in their closure, such as the Eve's Hangout at 129 MacDougal Street, after the deportation of Eva Kotchever for obscenity.[41]

As gay urban bohemia

The social repression of the 1950s resulted in a cultural revolution in Greenwich Village. A cohort of poets, later named the Beat poets, wrote about the evils of the social organization at the time, glorifying anarchy, drugs, and hedonistic pleasures over unquestioning social compliance, consumerism, and closed mindedness. Of them, Allen Ginsberg and William S. Burroughs—both Greenwich Village residents—also wrote bluntly and honestly about homosexuality. Their writings attracted sympathetic liberal-minded people, as well as homosexuals looking for a community.[42]

Strife in 1960s

By the early 1960s, a campaign to rid New York City of gay bars was in full effect by order of Mayor Robert F. Wagner, Jr., who was concerned about the image of the city in preparation for the 1964 World's Fair. The city revoked the liquor licenses of the bars, and undercover police officers worked to entrap as many homosexual men as possible.[43] Entrapment usually consisted of an undercover officer who found a man in a bar or public park, engaged him in conversation; if the conversation headed toward the possibility that they might leave together—or the officer bought the man a drink—he was arrested for solicitation. One story in the New York Post described an arrest in a gym locker room, where the officer grabbed his crotch, moaning, and a man who asked him if he was all right was arrested.[44] Few lawyers would defend cases as undesirable as these, and some of those lawyers kicked back their fees to the arresting officer.[45]

The Mattachine Society succeeded in getting newly elected Mayor John Lindsay to end the campaign of police entrapment in New York City. They had a more difficult time with the New York State Liquor Authority (SLA). While no laws prohibited serving homosexuals, courts allowed the SLA discretion in approving and revoking liquor licenses for businesses that might become "disorderly".[46] Despite the high population of gays and lesbians who called Greenwich Village home, very few places existed, other than bars, where they were able to congregate openly without being harassed or arrested. In 1966, the New York Mattachine held a "sip-in" at a Greenwich Village bar named Julius, which was frequented by gay men, to illustrate the discrimination homosexuals faced.[47]

None of the bars frequented by gays and lesbians were owned by gay people in the 1960s. Almost all of them were owned and controlled by organized crime, who treated the regulars poorly, watered down the liquor, and overcharged for drinks. However, they also paid off police to prevent frequent raids.[12]

Modern history

Greenwich Village contained the world's oldest gay and lesbian bookstore, Oscar Wilde Bookshop, founded in 1967 but permanently closed in 2009 citing the recession and the rise of online booksellers. The Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual & Transgender Community Center – best known as simply "The Center" – has occupied the former Food & Maritime Trades High School at 208 West 13th Street since 1984. In 2006, the Village was the scene of an assault involving seven lesbians and a straight man that sparked appreciable media attention, with strong statements both defending and attacking the parties. In June 2015, thousands gathered in front of the Stonewall Inn to celebrate the ruling by the U.S. Supreme Court affirming same-sex marriage in all fifty U.S. states, while in June 2016, thousands gathered similarly in vigil for the Orlando Pulse Nightclub massacre.[48] In February 2017, thousands protested at the Stonewall National Monument against the proposed policies of the administration of U.S. president Donald J. Trump affecting both LGBTQ individuals and international immigrants, including those holding the intersection of these identities.[49] In June 2019, the New York City Commission on Human Rights partnered with MasterCard International to commemorate the Stonewall 50 - WorldPride NYC 2019 milestone by planting a new street sign pan-inclusive for sexual orientations and gender identities at the intersection of Gay Street and Christopher Street in the West Village, and renaming that portion of Gay Street as Acceptance Street.[50]

Chelsea

Chelsea is one of the most gay-friendly neighborhoods in New York City.[51] In the 1990s, many gay people moved to the Chelsea neighborhood from the Greenwich Village neighborhood as a less expensive alternative; subsequent to this movement, house prices in Chelsea have increased dramatically to rival the West Village area of Greenwich Village.

Hell's Kitchen

The same phenomenon of gentrification in Greenwich Village which created a gay mecca in Chelsea has in turn spawned a new gay mecca in the Hell's Kitchen neighborhood on the West Side of Midtown Manhattan, just uptown, or north, of Chelsea, as gentrification has taken hold in Chelsea itself. The Metropolitan Community Church of New York, geared toward the LGBT community, is located in Hell's Kitchen.

Brooklyn

Brooklyn is home to a large and growing number of same-sex couples. Same-sex marriages in New York were legalized on June 24, 2011 and were authorized to take place beginning 30 days thereafter.[52] The Park Slope neighborhood spearheaded the popularity of Brooklyn among lesbians, and Prospect Heights has an LGBT residential presence.[36] Numerous neighborhoods have since become home to LGBT communities.

Queens

Adjacent Elmhurst and Jackson Heights, Queens, are focal hubs for the transgender community of New York City and collectively constitute the largest transgender hub in the world. The Queens Pride Parade is held in Jackson Heights each year.[7] Astoria has an emerging LGBT presence.[36] Queens is also becoming a destination for LGBT individuals priced out of still more expensive housing in Brooklyn.

NYC LGBT Historic Sites Project

The NYC LGBT Historic Sites Project[53] maps New York City's LGBT history, neighborhood by neighborhood; placing the city's LGBT history in a geographical context. Its interactive map features neighborhood sites important to NYC LGBT history in fields such as the arts, literature, and social justice, in addition to important gathering spaces, such as bars, clubs, and community centers.

Elsewhere in the New York City metropolitan region

As the LGBTQ community has achieved higher socioeconomic status and greater political clout over the decades, it has moved beyond the boundaries of New York City and spread out across the New York City metropolitan area. Westchester County in particular has spawned several gay villages concomitantly with hipster villages, notably in Hastings-on-Hudson, Dobbs Ferry, Irvington, and Tarrytown. Fire Island is the largest gay enclave on Long Island, followed by The Hamptons.[54] Gayborhoods have also emerged across the Hudson River from Manhattan in the U.S. state of New Jersey, in Asbury Park, Maplewood,[55] Montclair, and Lambertville. Trenton, the state capital of New Jersey, elected Reed Gusciora, its first openly gay mayor, in 2018.[56]

In June 2018, suburban Maplewood, New Jersey unveiled permanently rainbow-colored crosswalks to celebrate LGBTQ pride, a feature displayed by only a few other towns in the world,[57] including Rahway, New Jersey, which unveiled its own rainbow-colored crosswalks in June 2019.[58] In January 2019, New Jersey Governor Phil Murphy signed legislation mandating LGBTQ-inclusive educational curriculum in schools.[59] In February 2019, New Jersey began allowing a neutral or non-binary gender choice on birth certificates, while New York City already had this provision.[60]

Politics

Politics in New York City are mainly liberal. Rosenberg and Dunford stated that this political standpoint had historically been "generally beneficial to the gay community".[36]

In New York City, New York City Republican Party political administrations actively court LGBT voters.[36] LGBT voters were 3.4% of New York City's electorate in 1989.[61]

In the mid-1970s, LGBT participation in New York City politics began. In the 1977 Mayor of New York City elections, Edward Koch was the preferred candidate; there had been speculation that Koch was homosexual. However, Koch associated with religious figures opposed to homosexuality and did not pass LGBT civil rights bills, and therefore in 1981, Frank Barbaro became the candidate favored by the LGBT political groups.[62] In the 1985 mayoral election Koch had almost no support; Donald P. Haider-Markel, the author of Gay and Lesbian Americans and Political Participation: A Reference Handbook, wrote that Koch's "actions on AIDS seemed inadequate at best".[63] In the 1989 mayoral election, David Dinkins received support from the LGBT community.[61] Since then, every mayor has received support from the LGBT community, which included Rudy Giuliani and Mike Bloomberg.

Jimmy Van Bramer, the Majority Leader of the New York City Council in 2017, is an openly gay politician from Queens who has served in the City Council for over six years. Van Bramer was one of seven openly LGBT members of the New York City Council as of 2017, alongside Rosie Mendez, Corey Johnson, Ritchie Torres, James Vacca, Daniel Dromm and Carlos Menchaca. Christine Quinn served as Speaker of the New York City Council between 2006 and 2013. Carlos Menchaca also became the first Mexican American member of the New York City Council when elected in November 2013.

In June 2019, in celebration of LGBT Pride Month, Governor Andrew Cuomo ordered that the LGBT pride flag to be raised over the New York State Capitol for the first time in New York State history.[64]

Institutions

.jpg)

.jpg)

New York City publishes its LGBTQ Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, Transgender & Queer Guide of Services and Resources.[66]

The Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual & Transgender Community Center is located on West 13th Street in the West Village, Lower Manhattan.[67]

Services & Advocacy for GLBT Elders (SAGE) is the country's largest and oldest organization dedicated to improving the lives of lesbian, gay, bisexual and transgender people. SAGE is located at 305 Seventh Avenue, 15th Floor NYC, NY 10001. SAGE has expanded throughout New York City, with additional centers now located in Harlem, the Bronx, Brooklyn, and Staten Island.[68]

The Bronx Academy of Arts and Dance is a New York performing and visual art workshop space and performance venue located in The Bronx. Co-founded in 1998 by Arthur Aviles, dancer and choreographer who performed with the Bill T. Jones/Arnie Zane Dance Company, and Charles Rice-Gonzales, a writer, LGBT activist, and publicist. Focusing on works exploring the margins of Latino and LGBTQ cultures. The programs at BAAD! are made up of dancers, LGBTQ visual artists, women, and artists of color.[69]

The Bureau of General Services – Queer Division (BGSQD) is a queer cultural center, bookstore, and event space hosted by The Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual & Transgender Community Center in New York City.[70]

The Leslie Lohman Museum of Gay and Lesbian Art (LLM) is located in Soho, Lower Manhattan,[71] and is the only museum in the world dedicated to artwork documenting the LGBTQ experience.[65]

Lambda Legal is headquartered in New York City.[72]

The Lesbian Herstory Archives is located in a townhouse in Brooklyn. It has 12,000 photographs, over 11,000 books, 1,300 periodical titles, and 600 videos. There are also thousands of miscellaneous items.[71]

The Bronx Community Pride Center was previously located in the Bronx.[71] The city government had funded the nonprofit agency. Lisa Winters, who headed the agency from 2004 until 2010, had stolen $143,000 from the agency; she was ultimately fired. She was convicted of stealing the funds and misusing a credit card belonging to another person. In April 2013 she received a prison sentence of two concurrent terms, each two to six years. Winters' theft resulted in the closure of the agency.[73]

The New York City Subway system commemorates Pride Month in June with Pride-themed posters[74] and celebrated Stonewall 50 - WorldPride NYC 2019 in June 2019 with rainbow-themed Pride logos on the subway trains as well as Pride-themed MetroCards.[75]

New York City Pride March

The annual New York City Pride March traverses southward down Fifth Avenue and ends at Greenwich Village. The New York City Pride March rivals the Sao Paulo Gay Pride Parade as the largest pride parade in the world, attracting tens of thousands of participants and millions of sidewalk spectators each June.[76][77] The march passes by the site of the Stonewall Inn on Christopher Street, the location of the 1969 police raid which launched the modern LGBT rights movement.[78]

The march, the rally, PrideFest (the festival), and the Dance on the Pier are the main events of Pride Week in New York City LGBT Pride Week. Since 1984, Heritage of Pride (HOP) has been the producer and organizer of pride events in New York City.[79] The 2017 New York City Pride parade was the first in its history scheduled to be broadcast and streamed live.[80]

Stonewall 50 – WorldPride NYC 2019 was the largest international Pride celebration in history, produced by Heritage of Pride and enhanced through a partnership with the I ❤ NY program's LGBT division, commemorating the 50th anniversary of the Stonewall uprising, with 150,000 participants and five million spectators attending in Manhattan alone.[81] The events of 2019 were held throughout June, which is traditionally Pride month in New York City and worldwide, under the auspices of the annual NYC Pride March.

History of the New York City Pride parade

Early on the morning of Saturday, June 28, 1969, gay (LGBT) individuals rioted following a police raid on the Stonewall Inn, a gay bar at 53 Christopher Street, in the West Village of Lower Manhattan. This riot and further protests and rioting over the following nights were the watershed moment in modern LGBT Rights Movement and the impetus for organizing LGBT pride marches on a much larger public scale.

On November 2, 1969, Craig Rodwell, his partner Fred Sargeant, Ellen Broidy, and Linda Rhodes proposed the first pride march to be held in New York City by way of a resolution at the Eastern Regional Conference of Homophile Organizations (ERCHO) meeting in Philadelphia.[82]

That the Annual Reminder, in order to be more relevant, reach a greater number of people, and encompass the ideas and ideals of the larger struggle in which we are engaged-that of our fundamental human rights-be moved both in time and location.

We propose that a demonstration be held annually on the last Saturday in June in New York City to commemorate the 1969 spontaneous demonstrations on Christopher Street and this demonstration be called CHRISTOPHER STREET LIBERATION DAY. No dress or age regulations shall be made for this demonstration.

We also propose that we contact Homophile organizations throughout the country and suggest that they hold parallel demonstrations on that day. We propose a nationwide show of support.[83][84][85][86]

All attendees to the ERCHO meeting in Philadelphia voted for the march except for Mattachine Society of New York, which abstained.[83] Members of the Gay Liberation Front (GLF) attended the meeting and were seated as guests of Rodwell's group, Homophile Youth Movement in Neighborhoods (HYMN).[87]

Meetings to organize the march began in early January at Rodwell's apartment in 350 Bleecker Street.[88] At first there was difficulty getting some of the major New York organizations like Gay Activists Alliance (GAA) to send representatives. Craig Rodwell and his partner Fred Sargeant, Ellen Broidy, Michael Brown, Marty Nixon, and Foster Gunnison of Mattachine made up the core group of the CSLD Umbrella Committee (CSLDUC). For initial funding, Gunnison served as treasurer and sought donations from the national homophile organizations and sponsors, while Sargeant solicited donations via the Oscar Wilde Memorial Bookshop customer mailing list and Nixon worked to gain financial support from GLF in his position as treasurer for that organization.[89][90] Other mainstays of the organizing committee were Judy Miller, Jack Waluska, Steve Gerrie and Brenda Howard of GLF.[91] Believing that more people would turn out for the march on a Sunday, and so as to mark the date of the start of the Stonewall uprising, the CSLDUC scheduled the date for the first march for Sunday, June 28, 1970.[92] With Dick Leitsch's replacement as president of Mattachine NY by Michael Kotis in April 1970, opposition to the march by Mattachine ended.[93]

Brenda Howard, a bisexual activist, is known as the "Mother of Pride" for her work in coordinating the march, and she also originated the idea for a week-long series of events around Pride Day which became the genesis of the annual LGBT Pride celebrations that are now held around the world every June.[94][95] Additionally, Howard along with the bisexual activist Robert A. Martin (aka Donny the Punk) and gay activist L. Craig Schoonmaker are credited with popularizing the word "Pride" to describe these festivities.[96][97][98] Bisexual activist Tom Limoncelli later stated, "The next time someone asks you why LGBT Pride marches exist or why [LGBT] Pride Month is June tell them 'A bisexual woman named Brenda Howard thought it should be.'"[99][100]

—The New York Times coverage of Gay Liberation Day, 1970[101]

Christopher Street Liberation Day on June 28, 1970 marked the first anniversary of the Stonewall riots with an assembly on Christopher Street and the first LGBT Pride march in U.S. history, covering the 51 blocks to Central Park. The march took less than half the scheduled time due to excitement, but also due to wariness about walking through the city with gay banners and signs. Although the parade permit was delivered only two hours before the start of the march, the marchers encountered little resistance from onlookers.[102] The New York Times reported (on the front page) that the marchers took up the entire street for about 15 city blocks.[101] Reporting by The Village Voice was positive, describing "the out-front resistance that grew out of the police raid on the Stonewall Inn one year ago".[103]

New York City Drag culture

New York City's drag culture and ballroom culture have both displayed a prominent presence within the overall LGBTQ culture of New York City itself. Both the film Paris is Burning from 1990 and the more recent television series Pose have portrayed the fabric of ballroom culture.

New York City Drag March

The New York City Drag March, or NYC Drag March, is an annual drag protest and visibility march taking place in June, the traditional LGBTQ pride month in New York City.[104] Organized to coincide ahead of the NYC Pride March, both demonstrations commemorate the 1969 riots at the Stonewall Inn, widely considered the pivotal event sparking the gay liberation movement,[105][106][107][108] and the modern fight for LGBT rights.[109][110]

The Drag March takes place on Friday night as a kick-off to NYC Pride weekend.[111] The event starts in Tompkins Square Park and ends in front of the Stonewall Inn; it is purposefully non-corporate, punk, inclusive, and largely leaderless.[104]

In 2019 the 25th Drag March coincides with Stonewall 50 – WorldPride NYC 2019, anticipated to be the largest international LGBTQ event in history,[112] with many as four million people attending in Manhattan alone; the Drag March will take place June 28.[113]

Queens Pride Parade

The Queens Pride Parade and Multicultural Festival is the second oldest and second largest pride parade in New York City.[114][115] It is held annually in the neighborhood of Jackson Heights, located in the New York City borough of Queens. The parade was founded by Daniel Dromm and Maritza Martinez to raise the visibility of the LGBTQ community in Queens and memorialize Jackson Heights resident Julio Rivera.[116] Queens also serves as the largest transgender hub in the Western hemisphere and is the most ethnically diverse urban area in the world.[117]

Queer Liberation March

The Queer Liberation March is a protest march which was inaugurated in its current form on June 30, 2019, coincident with Stonewall 50 - WorldPride NYC 2019, marking the 50th anniversary of the Stonewall riots.[118][119] This march was created as a counterprotest to the corporate-focused sponsoring and participation requirements of the larger New York City Pride March, the result being a dueling major Manhattan LGBTQ march on the same day.[120][121] The march route proceeds uptown on Sixth Avenue in Manhattan, following the path of the fledgling first one, which in 1970 marked the one-year anniversary of the Stonewall Riots.[122] and was organized by the Christopher Street Liberation Day Committee.[123] The Queer Liberation March proceeds in the opposite direction of the New York City Pride March, which courses downtown on Fifth Avenue through most of its route.

LGBTQ media

LGBTQ publications include Gay City News, GO, and MetroSource.[36]

Out FM is an LGBT talk radio show.

Former publications include Gaysweek, The New York Blade, Next, and New York Native.

The film Paris is Burning documents the cultural contributions of gay, bisexual and trans New Yorkers mostly from Harlem ; especially those of color coming from mostly Black or Latino backgrounds. Much of the documentary centers around drag culture. African American and Latino members of the LGBT community in the 80s invented dances such as vogueing and coined terms such as 'reading' and 'throwing shade.' The independent documentary How Do I Look and the TV series Pose on FX expanded further upon the subject matter of and individuals appearing in Paris is Burning.

Celebrity-featured New York City LGBTQ-rights galas and festivities

New York City hosts a variety of LGBTQ-rights galas annually. The following is a list of some of these galas featuring the presence of celebrities:

- October 2004, Empire State Pride Agenda – Kimberly Guilfoyle[124]

- March 2010, amfAR, The Foundation for AIDS Research – Ricky Martin, Kylie Minogue[125]

- February 2017, Human Rights Campaign – Meryl Streep, Seth Meyers[126]

- New Year's Eve before 2019, surprise performance at the Stonewall Inn by Madonna[127]

- January 2019, New York City Women's March – U.S. Representative Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez (NY), giving a detailed speech in support of measures needed to ensure LGBTQ equality in the workplace and elsewhere;[128] she has also made a point of recognizing transgender rights specifically, saying, "It's a no-brainer...trans rights are civil rights are human rights."[129]

- The GLAAD Media Awards New York takes places annually[130] and features the attendance of highly prominent celebrities. The May 2019 event featured Rosie O'Donnell, Anderson Cooper, and Mykki Blanco presenting Madonna with a GLAAD Advocate for Acceptance award.[131]

- June 2019, surprise performance at the Stonewall Inn by Taylor Swift[132]

Education

The New York City Department of Education operates Harvey Milk High School in Manhattan; it caters to but is not limited to LGBT students.

Religion

Congregation Beit Simchat Torah ("CBST") is a Jewish synagogue located in Manhattan. It was founded in 1973[133] and describes itself as the world's largest LGBT synagogue.[134] The Metropolitan Community Church of New York (MCCNY) in the Hell's Kitchen neighborhood of Midtown Manhattan is affiliated with the worldwide Metropolitan Community Church.

The progressive Jewish congregation Kolot Chayeinu (Voices of our Lives) was founded by social justice activists Rabbi Ellen Lippmann and Cantor Lisa Segal. The current clergies are members of the LGBTQ community and a large portion of the congregation are members or affiliated with the LGBTQ community.

Recreation

Heritage of Pride or NYC Pride organizes LGBT community events such as the LGBT Pride March. The New York Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, & Transgender Film Festival is held in the city. MIX NYC organizes other LGBT film festivals. The Fresh Fruit Festival exhibits works of LGBT artists. The New York Gallery Tours company offers a monthly LGBT art gallery tour.[71]

Historically, the St. Patrick's Day Parade has not allowed openly LGBT groups to participate. However, the organizers announced that in 2015 the first LGBT group will be permitted to have a float.[135]

New York City Black Pride is held annually in August.[136]

Rainbow Book Fair, the largest LGBT book event in the U.S., is held annually every Spring in New York City.[137]

See also

- Culture of New York City

- Drag ball culture

- Gay Asian & Pacific Islander Men of New York

- Homosocialization

- LGBT Americans

- LGBT history in New York

- LGBT rights in New York

- LGBT rights in the United States

- List of self-identified LGBTQ New Yorkers

- New York City demographics

- New York City Gay Men's Chorus

- Pose (TV Series)

- The Queen (1968 film)

References

- Goicichea, Julia (August 16, 2017). "Why New York City Is a Major Destination for LGBT Travelers". The Culture Trip. Retrieved February 2, 2019.

- Rosenberg, Eli (June 24, 2016). "Stonewall Inn Named National Monument, a First for the Gay Rights Movement". The New York Times. Retrieved June 25, 2016.

- "Workforce Diversity The Stonewall Inn, National Historic Landmark National Register Number: 99000562". National Park Service, U.S. Department of the Interior. Retrieved April 21, 2016.

- Silverman, Brian. Frommer's New York City from $90 a Day (Volume 7 of Frommer's $ A Day). John Wiley & Sons, January 21, 2005. ISBN 0764588354, 9780764588358. p. 28.

- Rosenberg, Eli (June 24, 2016). "Stonewall Inn Named National Monument, a First for the Gay Rights Movement". The New York Times. Retrieved September 4, 2016.

- Gates, Gary J. (October 2006). "Same-sex Couples and the Gay, Lesbian, Bisexual Population: New Estimates from the American Community Survey" (PDF). The Williams Institute. Archived from the original (PDF) on January 15, 2013.

- Parry, Bill (July 10, 2018). "Elmhurst vigil remembers transgender victims lost to violence and hate". Queens Times Ledger. Retrieved November 11, 2018.

- Kaiser, p. xiv.

- Duberman, p. 183.

- Duberman, p. 185.

- Carter, p. 68.

- Duberman, p. 181.

- Carter, p. 80.

- Duberman, p. 182.

- Carter, p. 71.

- Duberman, p. 187.

- Duberman, p. 189.

- Duberman, p. 188.

- Deitcher, p. 70.

- Carter p. 74.

- Duberman, pp. 192–193.

- Carter, pp. 124–125.

- Eskow, Dennis (June 29, 1969). "4 Policemen Hurt in 'Village' Raid: Melee Near Sheridan Square Follows Action at Bar". The New York Times. p. 33. (subscription required)

- "NYC grants landmark status to gay rights movement building". NorthJersey.com. Associated Press. June 23, 2015. Archived from the original on March 3, 2016. Retrieved June 23, 2015.

- Carter, photo spread, p. 1.

- Carter, p. 137.

- Carter, pp. 96–103

- Carter, p. 142.

- Carter, p. 141.

- Williams, Cristan. "So, what was Stonewall?". The TransAdvocate. Retrieved October 26, 2016.

- "The Trans Community of Christopher Street". The New Yorker. August 1, 2016. Retrieved October 26, 2016.

- Patil, Anushka (June 15, 2020). "How a March for Black Trans Lives Became a Huge Event". The New York Times. Retrieved June 28, 2020.

- Keating, Shannon (June 6, 2020). "Corporate Pride Events Can't Happen This Year. Let's Keep It That Way". Retrieved June 28, 2020.

- Barone, Joshua (June 25, 2017). "A Winning Design for a New York Monument to Gay and Transgender People". The New York Times. Retrieved June 25, 2017.

- Lonely Planet New York City. Lonely Planet, September 1, 2012. ISBN 1743213468, 9781743213469. p. Google Books PT264 (Best LGBT section).

- Rosenberg, Andrew and Martin Dunford. The Rough Guide to New York. Penguin Books, January 1, 2011. ISBN 184836590X, 9781848365902. p. 379.

- "NYC The Official Guide - LGBTQ". NYC & Company. Retrieved September 24, 2016.

- Oliver, Isaac (January 2, 2017). "O Mad Night! 2016 ends with an 11-hour culture crawl through an opera, a house party, two concerts, a masquerade ball and an East Village gay bar". The New York Times. Retrieved January 2, 2017.

The Cock, a delightfully perverse gay bar on Second Avenue, ...

- Edsall, pp. 253–254.

- Edsall, pp. 255–256.

- Gattuso, Reina (September 3, 2019). "The Founder of America's Earliest Lesbian Bar Was Deported for Obscenity". Atlas Obscura.

- Adam, pp. 68–69.

- Carter, pp. 29–37.

- Carter, p. 46.

- Duberman, pp. 116–117.

- Carter, p. 48.

- Jackson, Sharyn (June 17, 2008). "Before Stonewall: Remembering that, before the riots, there was a Sip-In". The Village Voice. Retrieved September 8, 2008.

- Ismail, Aymann (June 14, 2016). "Grief and protest Mingle at the Stonewall Vigil for the Pulse Nightclub Massacre". Slate. Retrieved February 12, 2017.

- Murdock, Sebastian; Campbell, Andy (February 4, 2017). "LGBTQ Community Protests Trump At Historic Stonewall Inn". HuffPost. Retrieved February 4, 2017.

- White, Alexandria (June 17, 2019). "Mastercard launches True Name cards to make paying with credit cards easier for trans and non-binary communities". CNBC. Retrieved June 17, 2019.

Mastercard also partnered with the New York City Commission on Human Rights to create an all-inclusive version of the iconic street sign at the corner of Gay and Christopher Streets in New York City’s West Village, adding rainbow of street signs for each letter in the LGBTQIA+ acronym. This is just in time for WorldPride — which takes place in New York City this June — and the 50th anniversary of the Stonewall Riots.

- Parascandola, Rocco; Silverstein, Jason (September 18, 2016). "NYPD vetting Tumblr claiming to be Chelsea bomber 'manifesto'". Daily News. New York. Retrieved September 18, 2016.

- Confessore, Nicholas & Barbaro, Michael (June 24, 2011). "New York Allows Same-Sex Marriage, Becoming Largest State to Pass Law". The New York Times. Retrieved September 4, 2016.

- "Home". NYC LGBT Historic Sites Project. Retrieved August 30, 2019.

- Levy, Ariel. "Hamptons Heat Wave: Ladies Mile". New York. Retrieved September 17, 2017.

- Goldstein, Deborah (July 27, 2010). "Where the Gays Are - Are Maplewood and South Orange the gay-family Mecca of the tri-state area? Maplewood, NJ". Maplewood Patch. Retrieved September 14, 2016.

- Gross, Paige (July 1, 2018). "'I am honored': Trenton swears in Reed Gusciora as city's new mayor". The Star-Ledger. Retrieved July 1, 2018.

- Dryfoos, Delaney (June 7, 2018). "Town permanently painted crosswalk rainbow, because LGBT pride never goes away". The Star-Ledger. Retrieved June 27, 2018.

- Grom, Cassidy (June 12, 2019). "Facebook troll tried to take down N.J. town's rainbow crosswalks. It didn't work". New Jersey On-Line LLC. Retrieved June 12, 2019.

- Visser, Nick (January 31, 2019). "New Jersey Governor Signs Bill Requiring LGBTQ-Inclusive Curriculum In Schools. Gov. Phil Murphy was "honored" to sign the bill, an aide said". Huffpost. Retrieved February 1, 2019.

- "New Jersey Birth Certificate Laws". National Center for Transgender Equality - New Jersey. Retrieved February 1, 2019.

- Haider-Markel, Donald P. Gay and Lesbian Americans and Political Participation: A Reference Handbook (Political participation in America). ABC-CLIO, January 1, 2002. ISBN 1576072568, 9781576072561. p. 145.

- Haider-Markel, Donald P. Gay and Lesbian Americans and Political Participation: A Reference Handbook (Political participation in America). ABC-CLIO, January 1, 2002. ISBN 1576072568, 9781576072561. p. 144.

- Haider-Markel, Donald P. Gay and Lesbian Americans and Political Participation: A Reference Handbook (Political participation in America). ABC-CLIO, January 1, 2002. ISBN 1576072568, 9781576072561. p. 144-145.

- https://www.rochesterfirst.com/news/local-news/lgbtq-pride-flag-raised-over-thestatecapitol-for-the-first-time-in-ny-state-history/2055297395?

- Otterman, Sharon (June 28, 2019). "Highlights from the rally at the Stonewall Inn". The New York Times. Retrieved June 29, 2019.

- Scott M. Stringer, New York City Comptroller (June 2015). "LGBTQ Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, Transgender & Queer Guide of Services and Resources" (PDF). City of New York. Retrieved September 16, 2016.

- LGBT Center

- NYC SAGE Centers

- Bronx Academy of Arts and Dance

- BGSQD

- "NYC's 5 Best LGBT Art Exhibits And Cultural Events" (Archive). CBS New York City. June 4, 2012. Retrieved September 14, 2014.

- Lambda Legal

- Cunningham, Jennifer H. "Disgraced ex-head of Bronx Pride Center, Lisa Winters, sentenced to 2-6 years in prison for grand larceny" (Archive). Daily News|location=New York. Tuesday April 2, 2013. Retrieved September 14, 2014.

- Bass, Emily; Jones, Julia (June 16, 2019). "PRIDE + PROGRESS New York subways celebrate Pride Month with new 'Pride Trains' and MetroCards". CNN. Retrieved June 17, 2019.

- Guse, Clayton; Tracy, Thomas (June 14, 2019). "Everyone on board the Pride train! MTA celebrates LGBTQ culture with Pride-themed trains, MetroCards". Daily News. New York. Retrieved June 17, 2019.

- Ennis, Dawn (May 24, 2017). "ABC will broadcast New York's pride parade live for the first time". LGBTQ Nation. Retrieved September 26, 2018.

Never before has any TV station in the entertainment and news media capital of the world carried what organizer boast is the world's largest Pride parade live on TV.

- "Revelers Take To The Streets For 48th Annual NYC Pride March". CBS New York. June 25, 2017. Retrieved June 26, 2017.

A sea of rainbows took over the Big Apple for the biggest pride parade in the world Sunday.

- Stryker, Susan. "Christopher Street Gay Liberation Day: 1970". PlanetOut. Archived from the original on March 31, 2008. Retrieved September 13, 2016.

- "About Heritage Of Pride". Nyc Pride. Archived from the original on March 24, 2008. Retrieved September 13, 2016.

- Ennis, Dawn (May 24, 2017). "ABC will broadcast New York's pride parade live for the first time". LGBTQ Nation. Retrieved May 29, 2017.

- Accessed July 3, 2019.

- Sargeant, Fred. "1970: A First-Person Account of the First Gay Pride March." The Village Voice. June 22, 2010. retrieved January 3, 2011.

- Carter, p. 230

- Marotta, pp. 164–165

- Teal, pp. 322–323

- Duberman, pp. 255, 262, 270–280

- Duberman, p. 227

- Nagourney, Adam. "For Gays, a Party In Search of a Purpose; At 30, Parade Has Gone Mainstream As Movement's Goals Have Drifte." New York Times. June 25, 2000. retrieved September 13, 2016.

- Carter, p. 247

- Teal, p. 323

- Duberman, p. 271

- Duberman, p. 272

- Duberman, p. 314 n93

- Channel 13/WNET Out! 2007: Women In the Movement Archived January 18, 2008, at the Wayback Machine

- The Gay Pride Issue: Picking Apart The Origin of Pride Archived July 12, 2015, at the Wayback Machine

- Dynes, Wayne R. Pride (trope), Homolexis Archived July 12, 2011, at the Wayback Machine

- Donaldson, Stephen (1995). "The Bisexual Movement's Beginnings in the 70s: A Personal Retrospective". In Tucker, Naomi (ed.). Bisexual Politics: Theories, Queries, & Visions. New York: Harrington Park Press. pp. 31–45. ISBN 1-56023-869-0.

- Moor, Ashley (May 22, 2019). "Why Is It Called Pride?". MSN. Archived from the original on June 8, 2019. Retrieved June 8, 2019.

- In Memoriam – Brenda Howard

- Goodman, Elyssa. "Meet Brenda Howard, "The Mother of Pride" and a Pioneering Bisexual Activist". Them.us. Retrieved June 8, 2019.

- Fosburgh, Lacey (June 29, 1970). "Thousands of Homosexuals Hold A Protest Rally in Central Park", The New York Times, p. 1.

- Clendinen, p. 62–64.

- LaFrank, Kathleen (ed.) (January 1999). "National Historic Landmark Nomination: Stonewall", U.S. Department of the Interior: National Park Service.

- Dommu, Rose (June 25, 2018). "Hundreds Of Drag Queens Fill The NYC Streets Every Year For This 'Drag March'". HuffPost. Retrieved June 8, 2019.

- Goicichea, Julia (August 16, 2017). "Why New York City Is a Major Destination for LGBT Travelers". The Culture Trip. Retrieved February 2, 2019.

- "Brief History of the Gay and Lesbian Rights Movement in the U.S." University of Kentucky. Retrieved September 2, 2017.

- Frizzell, Nell (June 28, 2013). "Feature: How the Stonewall riots started the LGBT rights movement". Pink News UK. Retrieved August 19, 2017.

- "Stonewall riots". Encyclopædia Britannica. Retrieved August 19, 2017.

- U.S. National Park Service (October 17, 2016). "Civil Rights at Stonewall National Monument". Department of the Interior. Retrieved August 6, 2017.

- "Obama inaugural speech references Stonewall gay-rights riots". Archived from the original on May 30, 2013. Retrieved January 21, 2013.

- "See The Resplendent And Racy Queens And Kings Of NYC Drag March: Gothamist". amp.gothamist.com. Archived from the original on June 9, 2019. Retrieved June 9, 2019.

- Leonhardt, Andrea (April 30, 2019). "Whoopi Goldberg, Cyndi Lauper, Chaka Khan to Kick off WorldPride..." BK Reader. Retrieved May 24, 2019.

- Barrett, Jon (May 21, 2019). "What to see and do in NYC for World Pride". Newsday. Retrieved May 31, 2019.

- "Starting Point of First Queens Pride Parade". NYC LGBT Historic Sites Project. Retrieved March 28, 2019.

- "Queens kicks off Pride Month with annual parade". QNS.com. Retrieved March 28, 2019.

- Martinez, Arianna. "Queer Cosmopolis: The Evolution of Jackson Heights." In Planning and LGBTQ Communities: The Need for Inclusive Spaces. Ed. Petra L. Doan. New York: Routledge, 2015.

- Kim, Christine; Demand Media. "Queens, New York, Sightseeing". USA Today. Retrieved June 14, 2019.

- Silvers, Mara; WNYC. "LGBTQ Group Plans Alternative 'Queer Liberation March' On Pride Day". Gothamist. Archived from the original on May 15, 2019. Retrieved May 17, 2019.

- "'Queer Liberation March' sets stage for dueling NYC gay pride events". NBC News. Retrieved May 17, 2019.

- "NYC Activists Plan Alternative Gay Pride March for Same Day". The New York Times. Associated Press. May 14, 2019. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved May 17, 2019.

- "'Queer Liberation March' sets stage for dueling NYC gay pride events". NBC News. Retrieved May 30, 2019.

- The New York Public Library. "Christopher Street Liberation Day 1970". 1969: The Year of Gay Liberation. Retrieved May 17, 2019.

- "archives.nypl.org -- Christopher Street Liberation Day Committee records". archives.nypl.org. Retrieved May 17, 2019.

- Accessed February 12, 2017.

- Accessed February 12, 2017.

- Accessed February 12, 2017.

- Legaspi, Althea (January 1, 2019). "See Madonna's Surprise NYE 'Like a Prayer' Performance at Stonewall Inn". Rolling Stone. Retrieved June 15, 2019.

- Accessed February 18, 2019.

- Accessed February 18, 2019.

- Harvey, Spencer (May 5, 2019). "Madonna Declares "It Is Every Human's Duty To Fight, To Advocate" at the 30th Annual GLAAD Media Awards in New York". GLAAD. Retrieved May 13, 2019.

- Williams, David (June 15, 2019). "Taylor Swift gives surprise Pride Month performance at the Stonewall Inn". CNN. Retrieved June 15, 2019.

- "The LGBTQ Synagogue / About". Mission & Vision. Retrieved October 14, 2013.

- Lemberger, Michal (March 11, 2013). "Gay Synagogues' Uncertain Future: As mainstream acceptance grows—along with membership—gay congregations face unexpected questions". Tablet Magazine. Retrieved October 14, 2013.

- Sgueglia, Kristina and Ray Sanchez. "New York St. Patrick's Day parade to include first gay group" (Archive). CNN. September 3, 2014. Retrieved September 14, 2014.

- "NYC Black Pride Main Page". nycblackpride.com.

- https://rainbowbookfair.org

Further reading

- Chauncey, George. 1994. Gay New York: gender, urban culture, and the makings of the gay male world, 1890-1940. New York: Basic Books.

- Kaiser, Charles. The Gay Metropolis: The Landmark History of Gay Life in America. Grove Press, 2007. ISBN 0802143172, 9780802143174.

External links

- Brooklyn Community Pride Center

- Caribbean Equality Project

- Pride Center of Staten Island

- LGBTQ Community Services Center of The Bronx, Incorporated (Bronx LGBTQ Center)

- Bronx Community Pride Center (Archive)

- Gay Men's Health Crisis (GMHC)

- Audre Lorde Project

- LGBT Life in NYC

- Lesbian Archives

- SAGEUSA

- Stonewall Forever a Monument to 50 Years of Pride Stonewall Forever Monument