Battle of Picacho Pass

The Battle of Picacho Pass or the Battle of Picacho Peak was an engagement of the American Civil War on April 15, 1862. The action occurred around Picacho Peak, 50 miles (80 km) northwest of Tucson, Arizona. It was fought between a Union cavalry patrol from California and a party of Confederate pickets from Tucson, and marks the westernmost battle of the American Civil War.

| Battle of Picacho Pass | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the American Civil War | |||||||

Picacho Peak | |||||||

| |||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

|

|

| ||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

| James Barrett † | Henry Holmes (POW) | ||||||

| Strength | |||||||

| 13 cavalry | 10 cavalry | ||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||

| 3 killed, 3 wounded | 3 captured, 2 wounded (disputed) | ||||||

Background

After a Confederate force of about 120 cavalrymen arrived at Tucson from Texas on February 28, 1862, they proclaimed Tucson the capital of the western district of the Confederate Arizona Territory, which comprised what is now southern Arizona and southern New Mexico. Mesilla, near Las Cruces, was declared the territorial capital and seat of the eastern district of the territory. The property of Tucson Unionists was confiscated and they were jailed or driven out of town. Confederates hoped a flood of sympathizers in southern California would join them and give the Confederacy an outlet on the Pacific Ocean, but this never happened. California Unionists were eager to prevent this, and 2,000 Union volunteers from California, known as the California Column and led by Colonel James Henry Carleton, moved east to Fort Yuma, California, and by May 1862 had driven the small Confederate force back into Texas.[1]

Like most of the Civil War era engagements in Arizona (Dragoon Springs, Stanwix Station and Apache Pass) Picacho Pass occurred near remount stations along the former Butterfield Overland Stagecoach route, which opened in 1859 and ceased operations when the war began. This skirmish occurred about a mile northwest of Picacho Pass Station.

Battle

Twelve Union cavalry troopers and one scout (reported to be mountain man Pauline Weaver but in reality Tucson resident John W. Jones), commanded by Lieutenant James Barrett of the 1st California Cavalry, were conducting a sweep of the Picacho Peak area, looking for Confederates reported to be nearby. The Arizona Confederates were commanded by Sergeant Henry Holmes. Barrett was under orders not to engage them, but to wait for the main column to come up. However, "Lt. Barrett acting alone rather than in concert, surprised the Rebels and should have captured them without firing a shot, if the thing had been conducted properly." Instead, in midafternoon the lieutenant "led his men into the thicket single file without dismounting them. The first fire from the enemy emptied four saddles, when the enemy retired farther into the dense thicket and had time to reload. ... Barrett followed them, calling on his men to follow him." Three of the Confederates surrendered. Barrett secured one of the prisoners and had just remounted his horse when a bullet struck him in the neck, killing him. Fierce and confused fighting continued among the mesquite and arroyos for 90 minutes, with two more Union fatalities and three troopers wounded. Exhausted and leaderless, the Californians broke off the fight and the Arizona Rangers, minus three who surrendered, mounted and carried warning of the approaching Union army to Tucson. Barrett's disobedience of orders had cost him his life and lost any chance of a Union surprise attack on Tucson.

The Union troops retreated to the Pima Indian Villages and hastily built Fort Barrett (named for the fallen officer) at White's Mill, waiting to gather resources to continue the advance. However, with no Confederate reinforcements available, Captain Sherod Hunter and his men withdrew as soon as the column again advanced. The Union troops entered Tucson without any opposition.

The bodies of the two Union enlisted men killed at Picacho (George Johnson and William S Leonard) were later removed to the National Cemetery at the Presidio of San Francisco in San Francisco, California. However, Lieutenant Barrett's grave, near the present railroad tracks, remains undisturbed and unmarked.[2][3] Union reports claimed that two Confederates were wounded in the fight, but Captain Hunter in his official report mentioned no Confederate casualties other than the three men captured.

Aftermath

Before this engagement a Confederate cavalry patrol had advanced as far west as Stanwix Station, where it was burning the hay stored there when it was attacked by a patrol of the California Column. The Confederates had been burning hay stored at the stage stations in order to delay the Union advance from California. About the same time as the skirmish at Picacho Peak, a larger force of Confederates was thwarted in its attempt to advance northward from Santa Fe, New Mexico, in the Battle of Glorieta Pass. By July the Confederates had retreated to Texas, though pro-Confederate militia units operated in some areas until mid-1863. The following year, the Union organized its own territory of Arizona, dividing New Mexico along the state's current north–south border, extending control southward from the provisional capital of Prescott. Although the encounter at Picacho Pass was only a minor event in the Civil War, it can be considered the high-water mark of the Confederate West.

Re-enactment

Every March, Picacho Peak State Park hosts a re-enactment of the Civil War battles of Arizona and New Mexico, including the battle of Picacho Pass. The re-enactments now have grown so large that many more participants tend to be involved than took part in the actual engagements, and include infantry units and artillery as well as cavalry. The 2015 re-enactment, which was held March 22 and 23, also included re-enactments of the Battle of Valverde and the Battle of Glorieta Pass, both of which took place in relatively nearby New Mexico.[4]

Gallery

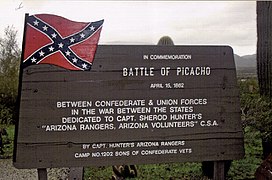

Battle of Picacho Marker.

Battle of Picacho Marker. Picacho Battle Field Marker.

Picacho Battle Field Marker. Battle of Picacho Monument.

Battle of Picacho Monument. Side view of the monument.

Side view of the monument. 2007 re-enactment of the Picacho Pass battle.

2007 re-enactment of the Picacho Pass battle.

Further reading

- "The Battle of Picacho Pass: Visiting the Battlefield and Historic Site". The War Times Journal. Retrieved October 19, 2010.

- Masich, Andrew E., The Civil War in Arizona; the Story of the California Volunteers, 1861–65; University of Oklahoma Press (Norman, 2006).

See also

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Battle of Picacho Pass. |

References

-

- Hart, Herbert M. "The Civil War in the West". California and the Civil War. The California State Military Museum. Retrieved 20 December 2011.

- Records of California Men in the War of the Rebellion 1861 to 1867 California Adjutant General Report 1890 .p.47 claimed the three Union soldiers killed were buried with twenty feet of the Southern Pacific Railroad which went through the pass

- Military History.com Barret is apparently buried where he was killed; a 1928 monument lists the names of the three union men killed

- The Arizona Republic, Skirmish in the Desert, Saturday March 14, 2015, page D! and D2