Timeline of ancient history

This timeline of ancient history lists historical events of the documented ancient past from the beginning of recorded history until the Early Middle Ages.

(Common Era years in astronomical year numbering) |

|

Millennia: 4th millennium BC - 3rd millennium BC - 2nd millennium BC - 1st millennium BC - 1st millennium

Centuries: 34th BC - 33rd BC - 32nd BC - 31st BC - 30th BC - 29th BC - 28th BC - 27th BC - 26th BC - 25th BC - 24th BC - 23rd BC - 22nd BC - 21st BC - 20th BC - 19th BC - 18th BC - 17th BC - 16th BC - 15th BC - 14th BC - 13th BC - 12th BC - 11th BC - 10th BC - 9th BC - 8th BC - 7th BC - 6th BC - 5th BC - 4th BC - 3rd BC - 2nd BC - 1st BC - 1st AD - 2nd AD - 3rd AD - 4th AD

Bronze Age and Early Iron Age

The Bronze Age was the period in human cultural development when the most advanced metalworking (at least in systematic and widespread use) included techniques for smelting copper and tin from naturally-occurring outcroppings of copper ores, and then combining those ores to cast bronze. These naturally-occurring ores typically included arsenic as a common impurity. Copper/tin ores are rare, as reflected in the fact that there were no tin bronzes in western Asia before 3000 BC. In some parts of the world, a Copper Age follows the Neolithic and precedes the Bronze Age.

The Iron Age was the stage in the development of any people in which tools and weapons whose main ingredient was iron were prominent. The adoption of this material coincided with other changes in some past societies often including differing agricultural practices, religious beliefs and artistic styles, although this was not always the case.

- c. 3200 BC: Sumerian cuneiform writing system[1] and Egyptian hieroglyphs

- 3200 BC: Newgrange built in Ireland

- 3200 BC: Cycladic culture in Greece

- 3200 BC: Norte Chico civilization begins in Peru

- 3200 BC: Rise of Proto-Elamite Civilization in Iran

- 3150 BC: First Dynasty of Egypt

- 3100 BC: Skara Brae in Scotland

- c. 3000 BC: Stonehenge construction begins. In its first version, it consisted of a circular ditch and bank, with 56 wooden posts.[2]

- c. 3000 BC: Cucuteni-Trypillian culture in Romania and Ukraine

- 3000 BC: Jiroft civilization begins in Iran

- 3000 BC: First known use of papyrus by Egyptians

- 2800 BC: Kot Diji phase of the Indus Valley Civilization begins

- 2800 BC: Longshan culture in China

- 2700 BC: Minoan Civilization ancient palace city Knossos reach 80,000 inhabitants

- 2700 BC: Rise of Elam in Iran

- 2700 BC: The Epic of Gilgamesh becomes the first written story

- 2700 BC: The Old Kingdom begins in Egypt

- 2600 BC: Oldest known surviving literature: Sumerian texts from Abu Salabikh, including the Instructions of Shuruppak and the Kesh temple hymn.

- 2600 BC: Mature Harappan phase of the Indus Valley civilization (in present-day Pakistan and India) begins

- 2600 BC: Emergence of Maya culture in the Yucatán Peninsula

- 2560 BC: King Khufu completes the Great Pyramid of Giza. The Land of Punt in the Horn of Africa first appears in Egyptian records around this time.

- 2500-1500 BC: Kerma culture in Nubia

- 2500 BC: The mammoth goes extinct.

- 2334 or 2270 BC: Akkadian Empire is founded, dating depends upon whether the Middle chronology or the Short chronology is used

- 2250 BC: Oldest known depiction of the Staff God, the oldest image of a god to be found in the Americas

- 2200-2100 BC: 4.2 kiloyear event: a severe aridification phase, likely connected to a Bond event, which was registered throughout most North Africa, Middle East and continental North America. Related droughts very likely caused the collapse of the Old Kingdom in Egypt and of the Akkadian Empire in Mesopotamia

- 2200 BC: completion of Stonehenge

- 2055 BC: The Middle Kingdom begins in Egypt

- 2000 BC: Domestication of the horse

- 1900 BC: Erlitou culture in China

- 1800 BC: alphabetic writing emerges

- 1800 BC: The Epic of Gilgamesh is written. Possibly the oldest great work of literature

- 1780 BC: Oldest Record of Hammurabi's Code.

- 1700 BC: Indus Valley Civilization comes to an end but is continued by the Cemetery H culture; The beginning of Poverty Point Civilization in North America

- 1600 BC: Minoan civilization on Crete is destroyed by the Minoan eruption of Santorini island

- 1600 BC: Mycenaean Greece

- 1600 BC: The beginning of Shang Dynasty in China, evidence of a fully developed writing system, see Oracle Bone Script

- 1600 BC: Beginning of Hittite dominance of the Eastern Mediterranean region

- c.1550 BC: The New Kingdom begins in Egypt

- 1500 BC: Composition of the Rigveda is completed

- 1700-1400 BCE: The Proto-sinaitic script is the oldest alphabet created in Egypt.

- c.1400 BC: Oldest known song with notation

- 1400-400 BC: Olmec civilization flourishes in Pre-Columbian Mexico, during Mesoamerica's Formative period

- 1200 BC: The Hallstatt culture

- 1200-1150 BC: Bronze Age collapse in Southwestern Asia and in the Eastern Mediterranean region. This period is also the setting of the Iliad and the Odyssey epic poems (which were composed about four centuries later).

- c. 1180 BC: Disintegration of Hittite Empire

- 1100 BC: Use of Iron spreads.

- 1046 BC: The Zhou force (led by King Wu of Zhou) overthrow the last king of Shang Dynasty; Zhou Dynasty established in China

- 1050 BCE: The Phoenician alphabet is created

- 1000 BC: Nok culture in West Africa

- 890 BC: Approximate date for the composition of the Iliad and the Odyssey

- 814 BC: Foundation of Carthage by the Phoenicians in today known Tunisia

- 800 BC: Rise of Greek city-states

- 788 BC: Iron Ancient in Sungai Batu (Old Kedah)

- c.785 BC: Rise of the Kingdom of Kush

Classical antiquity

Classical antiquity is a broad term for a long period of cultural history centered on the Mediterranean Sea, comprising the interlocking civilizations of Ancient Greece and Ancient Rome. It refers to the timeframe of Ancient Greece and Ancient Rome.[3][4] Ancient history includes the recorded Greek history beginning in about 776 BC (First Olympiad). This coincides roughly with the traditional date of the founding of Rome in 753 BC and the beginning of the history of Rome.[5][6]

- 776 BCE: First recorded Ancient Olympic Games.

- 753 BCE: Founding of Rome (traditional date)

- 745 BCE: Tiglath-Pileser III becomes the new king of Assyria. With time he conquers neighboring countries and turns Assyria into an empire.

- 728 BCE: Rise of the Median Empire.

- 722 BCE: Spring and Autumn period begins in China; Zhou Dynasty's power is diminishing; the era of the Hundred Schools of Thought.

- 700 BCE: The construction of Marib Dam in Arabia Felix.

- 653 BCE: Rise of Persian Empire.

- 612 BCE: An alliance between the Babylonians, Medes, and Scythians succeeds in destroying Nineveh and causing subsequent fall of the Assyrian empire.

- 600 BCE: Pandyan kingdom in South India.

- 600 BCE: Sixteen Maha Janapadas ("Great Realms" or "Great Kingdoms") emerge in India.

- 600 BCE: Evidence of writing system appear in Oaxaca used by the Zapotec civilization.

- c. 600 BCE: Rise of the Sao civilisation near Lake Chad

- 563 BCE: Siddhartha Gautama (Buddha), founder of Buddhism is born as a prince of the Shakya tribe, which ruled parts of Magadha, one of the Maha Janapadas.

- 551 BCE: Confucius, founder of Confucianism, is born.

- 550 BCE: Foundation of the Achaemenid Empire by Cyrus the Great.

- 549 BCE: Mahavira, founder of Jainism, is born.

- 546 BCE: Cyrus the Great overthrows Croesus King of Lydia.

- 544 BCE: Rise of Magadha as the dominant power under Bimbisara.

- 539 BCE: The fall of the Neo-Babylonian Empire and liberation of the Jews by Cyrus the Great.

- 529 BCE: Death of Cyrus

- 525 BCE: Cambyses II of Persia conquers Egypt.

- c. 512 BCE: Darius I (Darius the Great) of Persia, subjugates eastern Thrace, Macedonia submits voluntarily, and annexes Libya, Persian Empire at largest extent.

- 509 BCE: Expulsion of the last King of Rome, founding of Roman Republic (traditional date).

- 508 BCE: Democracy instituted at Athens

- c. 500 BCE: Completion of Euclid's Elements

- 500 BCE: Panini standardizes the grammar and morphology of Sanskrit in the text Ashtadhyayi. Panini's standardized Sanskrit is known as Classical Sanskrit.

- 500 BCE: Pingala uses zero and binary numeral system

- 499 BCE: King Aristagoras of Miletus incites all of Hellenic Asia Minor to rebel against the Persian Empire, beginning the Greco-Persian Wars.

- 490 BCE: Greek city-states defeat Persian invasion at Battle of Marathon

- 483 BCE: Death of Gautama Buddha

- 480 BCE: Persian invasion of Greece by Xerxes; Battles of Thermopylae and Salamis

- 479 BCE: Death of Confucius

- 475 BCE: Warring States period begins in China as the Zhou king became a mere figurehead; China is annexed by regional warlords

- 470/469 BCE: Birth of Socrates

- 465 BCE: Murder of Xerxes

- 460 BCE: Birth of Democritus

- 458 BCE: The Oresteia by Aeschylus, the only surviving trilogy of ancient Greek plays, is performed.

- 449 BCE: The Greco-Persian Wars end.

- 447 BCE: Building of the Parthenon at Athens started

- 432 BCE: Construction of the Parthenon is completed

- 431 BCE: Beginning of the Peloponnesian war between the Greek city-states

- 429 BCE: Sophocles's play Oedipus Rex is first performed

- 427 BCE: Birth of Plato

- 424 BCE: Nanda dynasty comes to power.

- 404 BCE: End of the Peloponnesian War

- 400 BCE: Zapotec culture flourishes around city of Monte Albán

- c. 400 BCE: Rise of the Garamantes as an irrigation-based desert state in the Fezzan region of Libya

- 399 BCE:Death of Socrates

- 384 BCE: Birth of Aristotle

- 370 BCE: Death of Democritus

- 331 BCE: Alexander the Great defeats Darius III of Persia in the Battle of Gaugamela, completing his conquest of Persia.

- 326 BCE: Alexander the Great defeats Indian king Porus in the Battle of the Hydaspes River.

- 323 BCE: Death of Alexander the Great at Babylon.

- 322 BCE: Death of Aristotle

- 321 BCE:Chandragupta Maurya overthrows the Nanda Dynasty of Magadha.

- 305 BCE: Chandragupta Maurya seizes the satrapies of Paropanisadai (Kabul), Aria (Herat), Arachosia (Qanadahar) and Gedrosia (Baluchistan)from Seleucus I Nicator, the Macedonian satrap of Babylonia, in return for 500 elephants.

- 300 BCE: Sangam literature (Tamil: சங்க இலக்கியம், Canka ilakkiyam) period in the history of ancient southern India (known as the Tamilakam)

- 300 BCE: Chola Empire in South India

- 300 BCE: Construction of the Great Pyramid of Cholula, the world's largest pyramid by volume (the Great Pyramid of Giza built 2560 BCE Egypt stands 146.5 meters, making it 91.5 meters taller), begins in Cholula, Puebla, Mexico.

- 273 BCE: Ashoka becomes the emperor of the Mauryan Empire

- 261 BCE: Kalinga war

- 257 BCE: Thục Dynasty takes over Việt Nam (then Kingdom of Âu Lạc)

- 255 BCE: Ashoka sends a Buddhist missionary led by his son who was Mahinda Thero (Buddhist monk) to Sri Lanka (then Lanka) Mahinda (Buddhist monk)

- 250 BCE: Rise of Parthia (Ashkâniân), the second native dynasty of ancient Persia

- 232 BCE: Death of Emperor Ashoka; Decline of the Mauryan Empire

- 230 BCE: Emergence of Satavahanas in South India

- 221 BCE: Qin Shi Huang unifies China, end of Warring States period; marking the beginning of Imperial rule in China which lasts until 1912. Construction of the Great Wall by the Qin Dynasty begins.

- 207 BC:lE: Kingdom of Nan Yue extends from Canton to North Việt Nam .

- 206 BCE: Han Dynasty established in China, after the death of Qin Shi Huang; China in this period officially becomes a Confucian state and opens trading connections with the West, i.e. the Silk Road.

- 202 BCE: Scipio Africanus defeats Hannibal at Battle of Zama.

- 200 BCE: El Mirador, largest early Maya city, flourishes.

- 200 BCE: Paper is invented in China.

- c. 200 BCE: Chera dynasty in South India.

- 185 BC: Shunga Empire founded.

- 167–160 BCE: Maccabean Revolt.

- 149–146 BCE: Third Punic War between Rome and Carthage. War ends with the complete destruction of Carthage, allowing Rome to conquer modern day Tunisia and Libya.

- 146 BCE: Roman conquest of Greece, see Roman Greece

- 121 BCE: Roman armies enter Gaul for the first time.

- 111 BCE: First Chinese domination of Việt Nam in the form of the Nanyue Kingdom.

- c. 100 BCE: Chola dynasty rises in prominence.

- c. 82 BCE: Burebista becomes the king of Dacia.

- c. 63 BCE: The Siege of Jerusalem (63 BC) leads to the conquest of Judea by the Romans.

- c. 60 BCE- 44 BCE: Burebista conquers territories from south Germany to Thrace,reaching the coast of the Aegean sea.

- 49 BCE: Roman Civil War between Julius Caesar and Pompey the Great.

- 44 BCE: Julius Caesar murdered by Marcus Brutus and others; End of Roman Republic; beginning of Roman Empire.

- 44 BCE: Burebista is assassinated in the same year like Julius Caesar and his empire breaks into 4 and later 5 kingdoms in modern-day Romania.

- 40 BCE: The Roman conquest of Egypt.

- 30 BCE: Cleopatra ends her reign as the last active ruler of the Ptolemaic Kingdom of Egypt

- 27 BCE: Formation of Roman Empire: Octavius is given titles of Princeps and Augustus by Roman Senate - beginning of Pax Romana. Formation of influential Praetorian Guard to provide security to Emperor

- 18 BCE: Three Kingdoms period begins in Korea. The temple of Jerusalem is reconstructed.

- 6 BCE: Earliest theorized date for birth of Jesus of Nazareth. Roman succession: Gaius Caesar and Lucius Caesar groomed for the throne.

- 4 BCE: Widely accepted date (Ussher) for birth of Jesus Christ.

- 9: Battle of the Teutoburg Forest, the Imperial Roman Army's bloodiest defeat.

- 14: Death of Emperor Augustus (Octavian), ascension of his adopted son Tiberius to the throne.

- 26-34: Crucifixion of Jesus Christ, exact date unknown.

- 37: Death of Emperor Tiberius, ascension of his nephew Caligula to the throne.

- 40: Rome conquers Mauretania.

- 41: Emperor Caligula is assassinated by the Roman senate. His uncle Claudius succeeds him.

- 43: Rome enters Britain for the first time.

- 54: Emperor Claudius dies and is succeeded by his grand nephew Nero.

- 68: Emperor Nero commits suicide, prompting the Year of the four emperors in Rome.

- 70: Destruction of Jerusalem by the armies of Titus.

- 79: Destruction of Pompeii by the volcano Vesuvius.

- 98: After a two-year rule, Emperor Nerva dies of natural causes, his adopted son Trajan succeeds him.

- 100-940: Kingdom of Aksum in the Horn of Africa

- 106-117: Roman Empire at largest extent under Emperor Trajan after having conquered modern-day Romania, Iraq and Armenia.

- 117: Trajan dies of natural causes. His adopted son Hadrian succeeds him. Hadrian pulls out of Iraq and Armenia.

- 122: Construction of Hadrian's Wall begins.

- 126: Hadrian completes the Pantheon in Rome.

- 138: Hadrian dies of natural causes. His adopted son Antoninus Pius succeeds him.

- 161: Death of Antoninus Pius. His rule was the only one in which Rome did not fight in a war.

- 161: Marcus Aurelius becomes emperor of the Roman Empire.

- 180: Reign of Marcus Aurelius officially ends.

- 180 - 181: Commodus becomes Roman Emperor.

- 192: Kingdom of Champa in Central Việt Nam.

- 200s: The Buddhist Srivijaya Empire established in Maritime Southeast Asia.

- 220: Three Kingdoms period begins in China after the fall of Han Dynasty.

- 226: Fall of the Parthian Empire and Rise of the Sassanian Empire.

- 238: Defeat of Gordian III (238–244), Philip the Arab (244–249), and Valerian (253–260), by Shapur I of Persia, (Valerian was captured by the Persians).

- 280: Emperor Wu established Jin Dynasty providing a temporary unity of China after the devastating Three Kingdoms period.

- 285: Diocletian becomes emperor of Rome and splits the Roman Empire into Eastern and Western Empires.

- 285: Diocletian begins a large-scale persecution of Christians.

- 292: The capital of the Roman empire is officially moved from Rome to Mediolanum (modern day Milan).

- 301: Diocletian's edict on prices

- 313: Edict of Milan declared that the Roman Empire would tolerate all forms of religious worship.

- 325: Constantine I organizes the First Council of Nicaea.

- 330: Constantinople is officially named and becomes the capital of the eastern Roman Empire.

- 335: Samudragupta becomes the emperor of the Gupta empire.

- 337: Emperor Constantine I dies, leaving his sons Constantius II, Constans I, and Constantine II as the emperors of the Roman empire.

- 350: Constantius II is left sole emperor with the death of his two brothers.

- 354: Birth of Augustine of Hippo

- 361: Constantius II dies, his cousin Julian succeeds him.

- 378: Battle of Adrianople, Roman army is defeated by the Germanic tribes.

- 380: Roman Emperor Theodosius I declares the Arian faith of Christianity heretical.

- 395: Theodosius I outlaws all religions other than Catholic Christianity.

- 406: Romans are expelled from Britain.

- 407-409: Visigoths and other Germanic tribes cross into Roman-Gaul for the first time.

- 410: Visigoths sacks Rome for the first time since 390 BC.

- 415: Germanic tribes enter Spain.

- 429: Vandals enter North Africa from Spain for the first time

- 439: Vandals have conquered the land stretching from Morocco to Tunisia by this time.

- 455: Vandals sack Rome, capture Sicily and Sardinia.

- c. 455: Skandagupta repels an Indo-Hephthalite attack on India.

- 476: Romulus Augustus, last Western Roman Emperor is forced to abdicate by Odoacer, a chieftain of the Germanic Heruli; Odoacer returns the imperial regalia to Eastern Roman Emperor Zeno in Constantinople in return for the title of dux of Italy; most frequently cited date for the end of ancient history.

End of ancient history in Europe

The date used as the end of the ancient era is arbitrary. The transition period from Classical Antiquity to the Early Middle Ages is known as Late Antiquity. Late Antiquity is a periodization used by historians to describe the transitional centuries from Classical Antiquity to the Middle Ages, in both mainland Europe and the Mediterranean world: generally from the end of the Roman Empire's Crisis of the Third Century (c. AD 284) to the Islamic conquests and the re-organization of the Byzantine Empire under Heraclius. The Early Middle Ages are a period in the history of Europe following the fall of the Western Roman Empire spanning roughly five centuries from AD 500 to 1000. Not all historians agree on the ending dates of ancient history, which frequently falls somewhere in the 5th, 6th, or 7th century. Western scholars usually date the end of ancient history with the fall of Rome in AD 476, the death of the emperor Justinian I in AD 565, or the coming of Islam in AD 632 as the end of ancient European history.

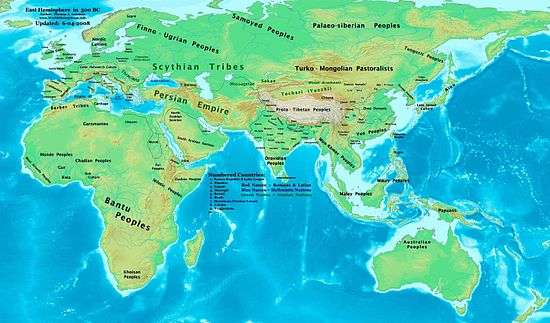

Maps

Eastern Hemisphere in 500 BC.

Eastern Hemisphere in 500 BC. Eastern Hemisphere in 323 BC.

Eastern Hemisphere in 323 BC. Eastern Hemisphere in 200 BC.

Eastern Hemisphere in 200 BC. Eastern Hemisphere in 100 BC.

Eastern Hemisphere in 100 BC. World in AD 1.

World in AD 1.- World in AD 100.

Eastern Hemisphere in AD 200.

Eastern Hemisphere in AD 200.- World in AD 300.

Eastern Hemisphere in AD 476.

Eastern Hemisphere in AD 476.

References

- Carr, E. H. (Edward Hallett). What is History?. Thorndike 1923, Becker 1931, MacMullen 1966, MacMullen 1990, Thomas & Wick 1993, Loftus 1996.

- Collingwood, R. G. (1946). The Idea of History. Oxford: Clarendon Press.

- Diamond, Jared (1999). Guns, Germs, and Steel: The Fates of Human Societies. New York: Norton.

- Dodds, E. R. (1964). The Greeks and the Irrational. Berkeley, Calif.: University of California Press.

- Kinzl, Konrad H. (1998). Directory of Ancient Historians in the USA, 2nd ed. Claremont, Calif.: Regina Books. ISBN 0-941690-87-3. Web edition is constantly updated.

- Kristiansen, Kristian; Larsson, Thomas B. (2005). The Rise of Bronze Age Society. Cambridge University Press.

- Libourel, Jan M. (1973). "A Battle of Uncertain Outcome in the Second Samnite War". The American Journal of Philology. Johns Hopkins University Press. 94 (1): 71–8. doi:10.2307/294039. ISSN 1086-3168. JSTOR 294039.

- "Livius. Articles on Ancient History".

- Lobell, Jarrett (July–August 2002). "Etruscan Pompeii". Archaeological Institute of America. 55 (4).

- Loftus, Elizbeth (1996). Eyewitness Testimony. Cambridge, Massachusetts: Harvard University Press. ISBN 0-674-28777-0.

- MacMullen, Ramsay (1966). Enemies of the Roman Order: Treason, Unrest and Alienation in the Empire. Cambridge, Massachusetts: Harvard University Press.

- MacMullen, Ramsay (1993). Changes in the Roman Empire: Essays in the Ordinary. Princeton, New Jersey: Princeton University Press. ISBN 0-691-03601-2.

- Thomas, Carol G.; D.P. Wick (1994). Decoding Ancient History: A Toolkit for the Historian as Detective. Englewood Cliffs, New Jersey: Prentice Hall. ISBN 0-13-200205-1.

- Thorndike, Lynn (1923–58). History of Magic and Experimental Science. New York: Macmillan. Eight volumes.

Citations and notes

- The invention of writing

- Caroline Alexander, "Stonehenge," National Geographic, June 2008.

- It is used to refer to various other periods of ancient history, like Ancient Egypt, ancient Mesopotamia (such as, Assyria, Babylonia and Sumer) or other early civilizations of the Near East. It is less commonly used in reference to civilizations of the Far East.

- William Smith, A Dictionary of Greek and Roman Antiquities. J. Murray, 1891

- Chris Scarre, The Penguin Historical Atlas of Ancient Rome (London: Penguin Books, 1995).

- Adkins, Lesley; Roy Adkins (1998). Handbook to Life in Ancient Rome. Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-512332-8. page 3.