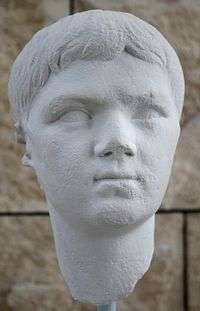

Lucius Caesar

Lucius Caesar (17 BC – 20 August AD 2) was a grandson of Augustus, the first Roman emperor. The son of Marcus Vipsanius Agrippa and Julia the Elder, Augustus' only daughter, Lucius was adopted by his grandfather along with his older brother, Gaius Caesar. As the emperor's adopted sons and joint-heirs to the Roman Empire, Lucius and Gaius had promising political and military careers. However, Lucius died of a sudden illness on 20 August AD 2, in Massilia, Gaul, while traveling to meet the Roman army in Hispania. His brother Gaius also died at a relatively young age on 21 February, AD 4. The untimely loss of both heirs compelled Augustus to redraw the line of succession by adopting Lucius' younger brother, Agrippa Postumus as well as his stepson, Tiberius on 26 June AD 4.

| Lucius Caesar | |

|---|---|

Lucius Caesar | |

| Born | Lucius Vipsanius Agrippa 17 BC |

| Died | 20 August AD 2 (aged 18) Massalia, Gaul |

| Burial | |

| Father |

|

| Mother | Julia the Elder |

Background

Marcus Vipsanius Agrippa was an early supporter of Augustus (then "Octavius") during the Final War of the Roman Republic that ensued as a result of the assassination of Julius Caesar in 44 BC. His father was a key general in Augustus' armies, commanding troops in pivotal battles against Mark Antony and Sextus Pompeius. From early in the emperor's reign, Agrippa was trusted to handle affairs in the eastern provinces and was even given the signet ring of Augustus, who was seemingly on his deathbed in 23 BC, a sign that he would become princeps were Augustus to die. It is probable that he was to rule until the emperor's nephew, Marcus Claudius Marcellus, came of age. However, Marcellus died of an illness that had spread throughout the city of Rome that year.[1][2][3]

With Marcellus gone, Augustus arranged for the marriage of Agrippa to his daughter Julia the Elder, who was previously the wife of Marcellus. Agrippa was given tribunicia potestas ("the tribunician power") in 18 BC, a power that only the emperor and his immediate heir could hope to attain. The tribunician power allowed him to control the Senate, and it was first given to Julius Caesar. Agrippa acted as tribune in the Senate to pass important legislation and, though he lacked some of the emperor's power and authority, he was approaching the position of co-regent.[3][4][5]

Early life and family

Lucius was born in Rome in 17 BC to Marcus Vipsanius Agrippa and Julia. He was part of the imperial family of Augustus, known as the Julio-Claudian dynasty, and was related to all the Julio-Claudian emperors. On his mother's side, he was the second oldest grandson of emperor Augustus after his brother Gaius. He was the brother-in-law of Tiberius by his half-sister Vipsania Agrippina, and Claudius by his sister Agrippina the Elder's marriage to Germanicus. Lucius' nephew was the future emperor Caligula, who was Germanicus' son.[6]

Having no heir since the death of Marcellus, Augustus immediately adopted Lucius and his brother from their father by a symbolic sale following Lucius' birth, and named the two boys his heirs.[7] It is unknown what their father thought of the adoption.[8] Shortly after their adoption in the summer, Augustus held the fifth ever Ludi Saeculares ("Secular Games"). The adoption of the boys coupled with the games served to introduce a new era of peace – the Pax Augusta. Augustus, mostly by himself, taught Gaius and Lucius how to read and swim, as well as how to imitate his own handwriting. He insisted that they earn the applause of people, instead of allowing them to receive it freely. Their adoptive father initiated them into administrative life when they were still young, and sent them to the provinces as consuls-elect.[9]

That year (17 BC) Lucius' family left for the province of Syria, because his father was given command of the eastern provinces with proconsular authority (imperium maius).[10] In 13 BC, his father returned to Rome and was promptly sent to Pannonia to suppress a rebellion. Agrippa arrived there that winter (in 12 BC), but the Pannonians gave up their plans. Agrippa returned to Campania in Italy, where he fell ill and died soon after.[11] The death of Lucius' father made succession a pressing issue. The aurei and denarii issued in 13–12 BC made clear the Emperor's dynastic plans for Lucius and Gaius. Their father was no longer available to assume the reins of power if the Emperor were to die, and Augustus had to make it clear who his intended heirs were in case anything should happen.[12]

Career

.jpg)

Augustus brought Lucius to the Forum Romanum in 2 BC to enroll him as a citizen. The event was made into a ceremony the same as Gaius' enrollment had been three years prior. Lucius assumed the toga virilis ("toga of manhood"), marking the beginning of his adulthood, and he too was made princeps iuventutis ("leader of the youth"). Like Gaius, he was elected consul designatus, with the intent that he assume the consulship at the age of nineteen. There was only one difference in his titles from those of Gaius: that he was made a member of the college of augurs whereas Gaius was made a pontifex ("pontiff"). Augustus distributed 60 denarii to each Roman citizen to mark the occasion.[13][14]

That same year, before his brother Gaius left for the east, Lucius and Gaius were given the authority to consecrate buildings, and they did, with their management of the games held to celebrate the dedication of the Temple of Mars Ultor (1 August 2 BC). Their younger brother, Postumus, participated in the Trojan games with the rest of the equestrian youth. 260 lions were slaughtered in the Circus Maximus, there was gladiatorial combat, a naval battle between the "Persians" and the "Athenians", and 36 crocodiles were slaughtered in the Circus Flaminius.[15][16]

While Gaius was in Armenia, Lucius had been sent by Augustus to complete his military training in Hispania. While on the way to his post, he fell ill and died on 20 August AD 2 in Massalia, Gaul.[17] His death was followed by that of Gaius on 21 February AD 4. In the span of 18 months, the succession of Rome was shaken.[18] The death of both Gaius and Lucius, the Emperor's two most favored heirs, led Augustus to adopt his stepson, Tiberius, and his sole remaining grandson, Postumus Agrippa as his new heirs on 26 June AD 4.[19]

Post mortem

The two heirs received many honours by citizens and city officials of the Empire, including Colonia Obsequens Iulia Pisana (Pisa), where it was decreed that proper rites must be observed by matrons to lament their passing. Temples, public baths, and shops shut their doors as women wept inconsolably. Posthumously the Senate voted honours for the young Caesars, and arranged for the golden spears and shields the boys had received on achieving the age of military service to be hung in the Senate House.[20] The caskets containing their ashes were stored in the Mausoleum of Augustus alongside those of their father Agrippa and other members of the imperial family.[20]

Tacitus and Cassius Dio both suggested that there may have been foul play involved in the death of Gaius and Lucius and that Lucius's step-grandmother Livia may have had a hand in their deaths. Livia's presumed motive may have been to orchestrate the accession of her own son Tiberius as heir to Augustus. Tiberius was named the heir of Augustus in AD 4.[21][22]

Ancestry

| Ancestry of Lucius Caesar[23] | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

References

- Bunson 2002, p. 10

- Southern 2013, p. 203

- Dunstan 2010, p. 274

- Rowe 2002, pp. 52–54

- Scullard 2013, p. 216

- Wood 1999, p. 321

- Cassius Dio, Roman History, LIV.18.1

- Davies & Swain 2010, p. 284

- Powell 2015, pp. 159–160

- Powell 2015, p. 161

- Cassius Dio, Roman History, LIV.28.1–2

- Wood 1999, p. 65

- Richardson 2012, p. 153

- Gibson 2012, p. 21

- Cassius Dio, Roman History, LV.10

- Lott 2004, pp. 124–125

- Mommsen 1996, p. 107

- Suetonius, The Lives of the Twelve Caesars, Life of Augustus, 65

- Pettinger 2012, p. 235

- Powell 2015, p. 192

- Cassius Dio, Roman History, LV.10a

- Tacitus, The Annals, I.3

- Bartsch 2017, p. ix

Bibliography

Ancient sources

Modern sources

- Bartsch, Shadi (2017), The Cambridge Companion to the Age of Nero, Cambridge University Press, ISBN 978-1-107-05220-8

- Bunson, Matthew (2002), Encyclopedia of the Roman Empire, Facts on File, ISBN 0-8160-4562-3

- Davies, Mark Everson; Swain, Hilary (2010), Aspects of Roman History 82BC-AD14: A Source-based Approach, Routledge, ISBN 978-1-135-15160-7

- Dunstan, William E. (2010), Ancient Rome, Rowman & Littlefield Publishers, ISBN 978-0-7425-6834-1

- Gibson, Alisdair (2012), The Julio-Claudian Succession: Reality and Perception of the "Augustan Model", Brill, ISBN 9789004231917

- Mommsen, Theodore (1996), A History of Rome Under the Emperors, UK: Routledge, ISBN 0-415-10113-1

- Pettinger, Andrew (2012), The Republic in Danger: Drusus Libo and the Succession of Tiberius, Oxford University Press, ISBN 978-0-19-960174-5

- Powell, Lindsay (2015), Marcus Agrippa:Right-hand Man of Caesar Augustus, Pen & Sword Military, ISBN 978-1-84884-617-3

- Lott, J. Bertt (2004), The Neighborhoods of Augustan Rome, Cambridge University Press, ISBN 978-0-521-82827-7

- Richardson, J.S. (2012), Augustan Rome 44 BC to AD 14: The Restoration of the Republic and the Establishment of the Empire, Edinburgh University Press, ISBN 978-0-7486-1954-2

- Rowe, Greg (2002), Princes and Political Cultures: The New Tiberian Senatorial Decress, University of Michigan Press, ISBN 0-472-11230-9

- Scullard, H. H. (2013), From the Gracchi to Nero: A History of Rome 133 BC to AD 68, Routledge, ISBN 978-1-136-78386-9

- Southern, Patricia (2013), Augustus, Routledge, ISBN 978-1-134-58956-2

- Wood, Susan E. (1999), Imperial Women: A Study in Public Images, 40 B.C. – A.D. 68, Brill Academic Publishers, ISBN 9789004119505