Edict on Maximum Prices

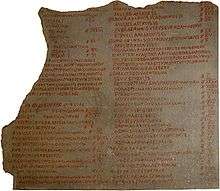

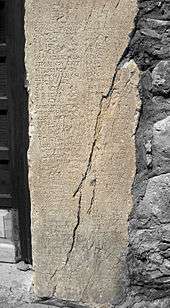

The Edict on Maximum Prices (Latin: Edictum de Pretiis Rerum Venalium, "Edict Concerning the Sale Price of Goods"; also known as the Edict on Prices or the Edict of Diocletian) was issued in 301 AD by Roman Emperor Diocletian.

The Edict was probably issued from Antioch or Alexandria and was set up in inscriptions in Greek and Latin. It now exists only in fragments found mainly in the eastern part of the empire, where Diocletian ruled. However, the reconstructed fragments have been sufficient to estimate many prices for goods and services for historical economists (although the Edict attempts to set maximum prices, not fixed ones).

The Edict on Maximum Prices is still the longest surviving piece of legislation from the period of the Tetrarchy. The Edict was criticized by Lactantius, a rhetorician from Nicomedia, who blamed the emperors for the inflation and told of fighting and bloodshed that erupted from price tampering.

By the end of Diocletian's reign in 305, the Edict was for all practical purposes ignored. The Roman economy as a whole was not substantively stabilized until Constantine's coinage reforms in the 310s.

History

During the Crisis of the Third Century, Roman coinage had been greatly debased by the numerous emperors and usurpers who minted their own coins, using base metals to reduce the underlying metallic value of coins used to pay soldiers and public officials.

Earlier in his reign, as well as in 301 around the same time as the Edict on Prices, Diocletian issued Currency Decrees, which attempted to reform the system of taxation and to stabilize the coinage.

It is difficult to know exactly how the coinage was changed, as the values and even the names of coins are often unknown or have been lost in the historical record. The Roman Empire was awash with other coins from outside of the Empire – especially in the Mediterranean. The implied coinage changeover time was at least a decade.

Although the decree was nominally successful for a short time after it was imposed, market forces led to more and more of the decree being disregarded and reinterpreted over time.

In the edict of Diocletian, it was mentioned that the wine from Picenum was considered the most expensive wine, together with Falerno.[1] Vinum Hadrianum was produced in Picenum,[2] in the city of Hatria or Hadria , the old city of Atri.[3]

Mechanics

The full mechanics of the decree have been lost. No full decree has been found, as it exists only in fragments. However, enough of the decree's text is known for the following to be understood to be true.

All coins in the Decrees and the Edict were valued according to the denarius, which Diocletian hoped to replace with a new system based on the silver argenteus and its fractions (although some modern writers call this the "denarius communis", this phrase is a modern invention, and is not found in any ancient text). The argenteus seems to have been set at 100 denarii, the silver-washed nummus at 25 denarii, and the bronze radiate at 4 or 5 denarii. The copper laureate was raised from 1 denarius to 2 denarii. The gold aureus was revalued at at least 1,200 denarii (although one document calls it a "solidus" it was still heavier than the solidus introduced by Constantine a few years later).

During the previous decades the decreasing amount of silver in the billon coins had fuelled inflation. This inflation is understood to be the reason the decree was issued. Issues of economic system feedback were not well understood at the time.

The first two-thirds of the Edict doubled the value of the copper and billon coins, and set the death penalty for profiteers and speculators, who were blamed for the inflation and who were compared to the barbarian tribes attacking the empire. Merchants were forbidden to take their goods elsewhere and charge a higher price, and transport costs could not be used as an excuse to raise prices.

The last third of the Edict, divided into 32 sections, imposed a price ceiling – a list of maxima – for well over a thousand products. These products included various food items (beef, grain, wine, beer, sausages, etc.), clothing (shoes, cloaks, etc.), freight charges for sea travel, and weekly wages. The highest limit was on one pound of purple-dyed silk, which was set at 150,000 denarii (the price of a lion was set at the same price).

Outcome

The Edict was counterproductive and deepened the existing crisis, jeopardizing the Roman economy even further. Diocletian's mass minting of coins of low metallic value continued to increase inflation, and the maximum prices in the Edict were apparently too low.

Merchants either stopped producing goods, sold their goods illegally, or used barter. The Edict tended to disrupt trade and commerce, especially among merchants. It is safe to assume that a black market economy evolved out of the edict at least between merchants.

Sometimes entire towns could no longer afford to produce trade goods. Because the Edict also set limits on wages, those who had fixed salaries (especially soldiers) found that their money was increasingly worthless as the artificial prices did not reflect actual costs.

Coinage

Each cell represents the ratio of the coin in the column to the coin in the row: thus 1000 denarii were worth 1 solidus.

| Solidus (coin) | Argenteus | Nummus | Radiate | Laureate | Denarius | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Solidus | 1 | 10 | 40 | 200 | 500 | 1,000 |

| Argentus | 1/10 | 1 | 4 | 20 | 50 | 100 |

| Nummus | 1/40 | 1/4 | 1 | 5 | 121⁄2 | 25 |

| Radiate | 1/200 | 1/20 | 1/5 | 1 | 21⁄2 | 5 |

| Laureate | 1/500 | 1/50 | 2/25 | 2/5 | 1 | 2 |

| Denarius | 1/1,000 | 1/100 | 1/25 | 1/5 | 1/2 | 1 |

References

- "The Common People of Ancient Rome, by Frank Frost Abbott". www.gutenberg.org. Retrieved 2020-03-17.

- Dalby, Andrew (2013-04-15). Food in the Ancient World from A to Z. Routledge. p. 171. ISBN 978-1-135-95422-2.

- Sandler, Merton; Pinder, Roger (2002-12-19). Wine: A Scientific Exploration. CRC Press. p. 66. ISBN 978-0-203-36138-2.

- Corcoran, Simon (2000). The Empire of the Tetrarchs, Imperial Pronouncements and Government AD 284–324. Oxford University Press. pp. 440 pages. ISBN 0-19-815304-X.

- Graser, E.R. (1940), "A text and translation of the Edict of Diocletian", in T. Frank (ed.), An Economic Survey of Ancient Rome Volume V: Rome and Italy of the Empire (1st ed.), Baltimore: Johns Hopkins Press

- Diocletianus emperor (1826), William Martin Leake (ed.), An edict ... fixing a maximum of prices throughout the Roman empire.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Edictum_de_pretiis. |

- Corcoran, Simon. "The Prices Edict at Geraki, Greece" (video). Retrieved 16 December 2009.

- Erim, K.T.; Reynolds, Joyce; White, K.D.; Charlesworth, Dorothy. 1973, 'The Aphrodisias Copy of Diocletian's Edict on Maximum Prices,' in JRS at https://www.jstor.org/stable/299169

- Kropff, Antony, 2016: New English translation of the Price Edict of Diocletianus, at https://www.academia.edu/23644199/New_English_translation_of_the_Price_Edict_of_Diocletianus

- Prices given in the price edict as compared with modern prices, at http://www.civilization.org.uk/decline-and-fall/diocletian/the-price-edict

- The Edict of Diocletian: A Case Study in Price Controls and Inflation, Murray Rothbard

- Price fixing in Ancient Rome, Robert L. Scheuttinger, Eamonn F. Butler