Thebes, Greece

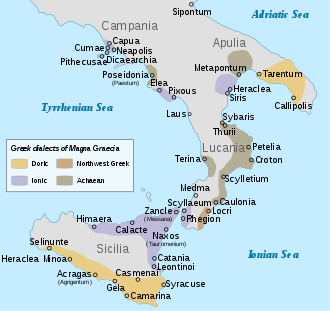

Thebes (/θiːbz/; Greek: Θήβα, Thíva [ˈθiva]; Ancient Greek: Θῆβαι, Thêbai [tʰɛ̂ːbai̯][2]) is a city in Boeotia, central Greece. It played an important role in Greek myths, as the site of the stories of Cadmus, Oedipus, Dionysus, Heracles and others. Archaeological excavations in and around Thebes have revealed a Mycenaean settlement and clay tablets written in the Linear B script, indicating the importance of the site in the Bronze Age.

Thebes Θήβα | |

|---|---|

Remains of the Cadmea, the central fortress of ancient Thebes | |

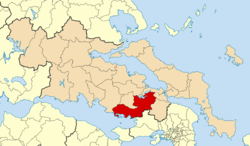

Thebes Location within the region  | |

| Coordinates: 38°19′N 23°19′E | |

| Country | Greece |

| Administrative region | Central Greece |

| Regional unit | Boeotia |

| Area | |

| • Municipality | 830.112 km2 (320.508 sq mi) |

| • Municipal unit | 321.015 km2 (123.945 sq mi) |

| Elevation | 215 m (705 ft) |

| Population (2011)[1] | |

| • Municipality | 36,477 |

| • Municipality density | 44/km2 (110/sq mi) |

| • Municipal unit | 25,845 |

| • Municipal unit density | 81/km2 (210/sq mi) |

| Demonym(s) | Theban |

| Community | |

| • Population | 22,883 (2011) |

| • Area (km2) | 143.889 |

| Time zone | UTC+2 (EET) |

| • Summer (DST) | UTC+3 (EEST) |

| Postal code | 32200 |

| Area code(s) | 22620 |

| Website | www |

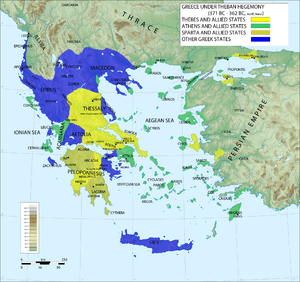

Thebes was the largest city of the ancient region of Boeotia and was the leader of the Boeotian confederacy. It was a major rival of ancient Athens, and sided with the Persians during the 480 BC invasion under Xerxes. Theban forces under the command of Epaminondas ended the power of Sparta at the Battle of Leuctra in 371 BC. The Sacred Band of Thebes (an elite military unit) famously fell at the Battle of Chaeronea in 338 BC against Philip II and Alexander the Great. Prior to its destruction by Alexander in 335 BC, Thebes was a major force in Greek history, and was the most dominant city-state at the time of the Macedonian conquest of Greece. During the Byzantine period, the city was famous for its silks.

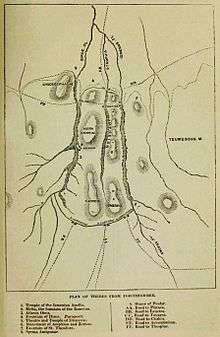

The modern city contains an Archaeological Museum, the remains of the Cadmea (Bronze Age and forward citadel), and scattered ancient remains. Modern Thebes is the largest town of the regional unit of Boeotia.

Geography

Thebes is situated in a plain, between Lake Yliki (ancient Hylica) to the north, and the Cithaeron mountains, which divide Boeotia from Attica, to the south. Its elevation is 215 metres (705 feet) above mean sea level. It is about 50 kilometres (31 miles) northwest of Athens, and 100 kilometres (62 miles) southeast of Lamia. Motorway 1 and the Athens–Thessaloniki railway connect Thebes with Athens and northern Greece. The municipality of Thebes covers an area of 830.112 square kilometres (320.508 square miles), the municipal unit of Thebes 321.015 square kilometres (123.945 square miles) and the community 143.889 square kilometres (55.556 square miles).[3]

Municipality

In 2011, as a consequence of the Kallikratis reform, Thebes was merged with Plataies, Thisvi, and Vagia to form a larger municipality, which retained the name Thebes. The other three become units of the larger municipality.[4]

History

Mythic record

The record of the earliest days of Thebes was preserved among the Greeks in an abundant mass of legends that rival the myths of Troy in their wide ramification and the influence that they exerted on the literature of the classical age. Five main cycles of story may be distinguished:

- The foundation of the citadel Cadmea by Cadmus, and the growth of the Spartoi or "Sown Men" (probably an aetiological myth designed to explain the origin of the Theban nobility which bore that name in historical times).

- The immolation of Semele and the advent of Dionysus.

- The building of a "seven-gated" wall by Amphion, and the cognate stories of Zethus, Antiope and Dirce.

- The tale of Laius, whose misdeeds culminated in the tragedy of Oedipus and the wars of the "Seven Against Thebes", the Epigoni, and the downfall of his house; Laius' pederastic rape of Chrysippus was held by some ancients to have been the first instance of homosexuality among mortals, and may have provided an etiology for the practice of pedagogic pederasty for which Thebes was famous. See Theban pederasty and Pederasty in ancient Greece for detailed discussion and background.

- The exploits of Heracles.

The Greeks attributed the foundation of Thebes to Cadmus, a Phoenician king from Tyre (now in Lebanon) and the brother of Queen Europa. Cadmus was famous for teaching the Phoenician alphabet and building the Acropolis, which was named the Cadmeia in his honor and was an intellectual, spiritual, and cultural center.

Early history

Archaeological excavations in and around Thebes have revealed cist graves dated to Mycenaean times containing weapons, ivory, and tablets written in Linear B. Its attested name forms and relevant terms on tablets found locally or elsewhere include 𐀳𐀣𐀂, te-qa-i,[n 1] understood to be read as *Tʰēgʷai̮s (Ancient Greek: Θήβαις, Thēbais, i.e. "at Thebes", Thebes in the dative-locative case), 𐀳𐀣𐀆, te-qa-de,[n 2] for *Tʰēgʷasde (Θήβασδε, Thēbasde, i.e. "to Thebes"),[2][6] and 𐀳𐀣𐀊, te-qa-ja,[n 3] for *Tʰēgʷaja (Θηβαία, Thēbaia, i.e. "Theban woman").[2]

It seems safe to infer that *Tʰēgʷai was one of the first Greek communities to be drawn together within a fortified city, and that it owed its importance in prehistoric days — as later — to its military strength. Deger-Jalkotzy claimed that the statue base from Kom el-Hetan in Amenhotep III's kingdom (LHIIIA:1) mentions a name similar to Thebes, spelled out quasi-syllabically in hieroglyphs as d-q-e-i-s, and considered to be one of four tj-n3-jj (Danaan?) kingdoms worthy of note (alongside Knossos and Mycenae). *Tʰēgʷai in LHIIIB lost contact with Egypt but gained it with "Miletus" (Hittite: Milawata) and "Cyprus" (Hittite: Alashija). In the late LHIIIB, according to Palaima,[7] *Tʰēgʷai was able to pull resources from Lamos near Mount Helicon, and from Karystos and Amarynthos on the Greek side of the isle of Euboia.

As a fortified community, it attracted attention from the invading Dorians, and the fact of their eventual conquest of Thebes lies behind the stories of the successive legendary attacks on that city.

The central position and military security of the city naturally tended to raise it to a commanding position among the Boeotians, and from early days its inhabitants endeavoured to establish a complete supremacy over their kinsmen in the outlying towns. This centralizing policy is as much the cardinal fact of Theban history as the counteracting effort of the smaller towns to resist absorption forms the main chapter of the story of Boeotia. No details of the earlier history of Thebes have been preserved, except that it was governed by a land-holding aristocracy who safeguarded their integrity by rigid statutes about the ownership of property and its transmission over time.

Archaic and classical periods

As attested already in Homer's Iliad, Thebes was often called "Seven-Gated Thebes" (Θῆβαι ἑπτάπυλοι, Thebai heptapyloi) (Iliad, IV.406) to distinguish it from "Hundred-Gated Thebes" (Θῆβαι ἑκατόμπυλοι, Thebai hekatompyloi) in Egypt (Iliad, IX.383).

In the late 6th century BC, the Thebans were brought for the first time into hostile contact with the Athenians, who helped the small village of Plataea to maintain its independence against them, and in 506 BC repelled an inroad into Attica. The aversion to Athens best serves to explain the apparently unpatriotic attitude which Thebes displayed during the Persian invasion of Greece (480–479 BC). Though a contingent of 400 was sent to Thermopylae and remained there with Leonidas before being defeated alongside the Spartans,[8] the governing aristocracy soon after joined King Xerxes I of Persia with great readiness and fought zealously on his behalf at the Battle of Plataea in 479 BC. The victorious Greeks subsequently punished Thebes by depriving it of the presidency of the Boeotian League and an attempt by the Spartans to expel it from the Delphic amphictyony was only frustrated by the intercession of Athens.

In 457 BC Sparta, needing a counterpoise against Athens in central Greece, reversed her policy and reinstated Thebes as the dominant power in Boeotia. The great citadel of Cadmea served this purpose well by holding out as a base of resistance when the Athenians overran and occupied the rest of the country (457–447 BC). In the Peloponnesian War, the Thebans, embittered by the support that Athens gave to the smaller Boeotian towns, and especially to Plataea, which they vainly attempted to reduce in 431 BC, were firm allies of Sparta, which in turn helped them to besiege Plataea and allowed them to destroy the town after its capture in 427 BC. In 424 BC, at the head of the Boeotian levy, they inflicted a severe defeat on an invading force of Athenians at the Battle of Delium, and for the first time displayed the effects of that firm military organization that eventually raised them to predominant power in Greece.

After the downfall of Athens at the end of the Peloponnesian War, the Thebans, having learned that Sparta intended to protect the states that Thebes desired to annex, broke off the alliance. In 404 BC, they had urged the complete destruction of Athens; yet, in 403 BC, they secretly supported the restoration of its democracy in order to find in it a counterpoise against Sparta. A few years later, influenced perhaps in part by Persian gold, they formed the nucleus of the league against Sparta. At the Battle of Haliartus (395 BC) and the Battle of Coronea (394 BC), they again proved their rising military capacity by standing their ground against the Spartans. The result of the war was especially disastrous to Thebes, as the general settlement of 387 BC stipulated the complete autonomy of all Greek towns and so withdrew the other Boeotians from its political control. Its power was further curtailed in 382 BC, when a Spartan force occupied the citadel by a treacherous coup-de-main. Three years later, the Spartan garrison was expelled and a democratic constitution was set up in place of the traditional oligarchy. In the consequent wars with Sparta, the Theban army, trained and led by Epaminondas and Pelopidas, proved itself formidable (see also: Sacred Band of Thebes). Years of desultory fighting, in which Thebes established its control over all Boeotia, culminated in 371 BC in a remarkable victory over the Spartans at Leuctra. The winners were hailed throughout Greece as champions of the oppressed. They carried their arms into Peloponnesus and at the head of a large coalition, permanently crippled the power of Sparta, in part by freeing many helot slaves, the basis of the Spartan economy. Similar expeditions were sent to Thessaly and Macedon to regulate the affairs of those regions.

Decline and destruction

However, the predominance of Thebes was short-lived, as the states that it protected refused to subject themselves permanently to its control. Thebes renewed rivalry with Athens, who had joined with them in 395 BC in fear of Sparta, but since 387 BC had endeavored to maintain the balance of power against its ally, prevented the formation of a Theban empire. With the death of Epaminondas at the Battle of Mantinea (362 BC), the city sank again to the position of a secondary power.

In the Third Sacred War (356—346 BC) with its neighbor Phocis, Thebes lost its predominance in central Greece. By asking Philip II of Macedon to crush the Phocians, Thebes extended the former's power within dangerous proximity to its frontiers. The revulsion of popular feeling in Thebes was expressed in 338 BC by the orator Demosthenes, who persuaded Thebes to join Athens in a final attempt to bar Philip's advance on Attica. The Theban contingent lost the decisive battle of Chaeronea and along with it every hope of reassuming control over Greece.

Philip was content to deprive Thebes of its dominion over Boeotia; but an unsuccessful revolt in 335 BC against his son Alexander the Great while he was campaigning in the north was punished by Alexander and his Greek allies with the destruction of the city (except, according to tradition, the house of the poet Pindar and the temples), and its territory divided between the other Boeotian cities. Moreover, the Thebans themselves were sold into slavery.[9]

Alexander spared only priests, leaders of the pro-Macedonian party and descendants of Pindar. The end of Thebes cowed Athens into submission. According to Plutarch, a special Athenian embassy, led by Phocion, an opponent of the anti-Macedonian faction, was able to persuade Alexander to give up his demands for the exile of leaders of the anti-Macedonian party, and most particularly Demosthenes and not sell the people into slavery .[10]

Hellenistic and Roman periods

Ancient writings tend to treat Alexander's destruction of Thebes as excessive.[11] Plutarch, however, writes that Alexander grieved after his excess, granting them any request of favors, and advising they pay attention to the invasion of Asia, and that if he failed, Thebes might once again become the ruling city-state.[12] Although Thebes had traditionally been antagonistic to whichever state led the Greek world, siding with the Persians when they invaded against the Athenian-Spartan alliance, siding with Sparta when Athens seemed omnipotent, and famously derailing the Spartan invasion of Persia by Agesilaus. Alexander's father Philip had been raised in Thebes, albeit as a hostage, and had learnt much of the art of war from Pelopidas. Philip had honoured this fact, always seeking alliances with the Boeotians, even in the lead-up to Chaeronea. Thebes was also revered as the most ancient of Greek cities, with a history of over 1,000 years. Plutarch relates that, during his later conquests, whenever Alexander came across a former Theban, he would attempt to redress his destruction of Thebes with favours to that individual.

Restoration by Cassander

Following Alexander the Great's death in 323 BC, Thebes was re-established in 315 BC[13] by Alexander's successor, Cassander.[14] In restoring Thebes, Cassander sought to rectify the perceived wrongs of Alexander - a gesture of generosity that earned Cassander much goodwill throughout Greece.[15] In addition to currying favor with the Athenians and many of the Peloponnesian states, Cassander's restoration of Thebes provided him with loyal allies in the Theban exiles who returned to resettle the site.[15]

Cassander's plan for rebuilding Thebes called for the various Greek city-states to provide skilled labor and manpower, and ultimately it proved successful.[15] The Athenians, for example, rebuilt much of Thebes' wall.[15] Major contributions were sent from Megalopolis, Messene, and as far away as Sicily and Italy.[15]

Despite the restoration, Thebes never regained its former prominence. The death of Cassander in 297 BC created a power vacuum throughout much of Greece, which contributed, in part, to Thebes' besiegement by Demetrius Poliorcetes in 293 BC, and again after a revolt in 292 BC. This last siege was difficult and Demetrius was wounded, but finally he managed to break down the walls and to take the city once more, treating it mildly despite its fierce resistance. The city recovered its autonomy from Demetrius in 287 BC, and became allied with Lysimachus and the Aetolian League.

Byzantine period

During the early Byzantine period it served as a place of refuge against foreign invaders. From the 10th century, Thebes became a centre of the new silk trade, its silk workshops boosted by imports of soaps and dyes from Athens. The growth of this trade in Thebes continued to such an extent that by the middle of the 12th century, the city had become the biggest producer of silks in the entire Byzantine empire, surpassing even the Byzantine capital, Constantinople. The women of Thebes were famed for their skills at weaving. Theban silk was prized above all others during this period, both for its quality and its excellent reputation.

Though severely plundered by the Normans in 1146, Thebes quickly recovered its prosperity and continued to grow rapidly until its conquest by the Latins of the Fourth Crusade in 1204.

Latin period

Thanks to its wealth, the city was selected by the Frankish dynasty de la Roche as its capital, before it was permanently moved to Athens. After 1240, the Saint Omer family controlled the city jointly with the de la Roche dukes. The castle built by Nicholas II of Saint Omer on the Cadmea was one of the most beautiful of Frankish Greece. After its conquest in 1311 the city was used as a capital by the short-lived state of the Catalan Company.

In 1379, the Navarrese Company took the city with the aid of the Latin Archbishop of Thebes, Simon Atumano.[n 4]

Ottoman period

Latin hegemony in Thebes lasted to 1458, when the Ottomans captured it. The Ottomans renamed Thebes "İstefe" and managed it until the War of Independence (1821, nominally to 1832) except for a Venetian interlude between 1687 and 1699.

Modern town

In the modern Greek State, Thebes was the capital of the prefecture of Boeotia until the late 19th century, when Livadeia became the capital.

Today, Thebes is a bustling market town, known for its many products and wares. Until the 1980s, it had a flourishing agrarian production with some industrial complexes. However, during the late 1980s and 1990s the bulk of industry moved further south, closer to Athens. Tourism in the area is based mainly in Thebes and the surrounding villages, where many places of interest related to antiquity exist such as the battlefield where the Battle of Plataea took place. The proximity to other, more famous travel destinations, like Athens and Chalkis, and the undeveloped archaeological sites have kept the tourist numbers low.

Thebes, 1842 by Carl Rottmann

Thebes, 1842 by Carl Rottmann_-_1887.jpg) Popular festival at Thebes, 1880s

Popular festival at Thebes, 1880s- A bust of Pindar

Entrance to the archaeological museum

Entrance to the archaeological museum Monastery of Transfiguration

Monastery of Transfiguration

Notable people

Ancient

- Attaginus, oligarch

- Epaminondas (c. 418-362 BC) general and statesman - Commanded the Theban forces at the battles of Leuctra and Mantinea

- Pelopidas (c. 420 - 365) general and statesman - Led rebellion against Sparta, commanded the Theban "Sacred band" at Leuctra

- Aristides (4th century BC) painter

- Nicomachus (4th century BC) painter

- Crates of Thebes (c. 365-c. 285 BC) Cynic philosopher

- Kleitomachos (3rd century BC) athlete

- Pindar (c. 522–443 BC), poet

- Luke the Evangelist, died and buried here

Modern

- Pandelis Pouliopoulos, Greek communist politician

- Haris Alexiou (born 1950), singer

- Panagiotis Bratsiotis, theologian

- Theodoros Vryzakis (c. 1814 – 1878) painter

- Alexandros Merentitis, military officer

- Archbishop Ieronymos II of Athens

See also

- Boeotia

- Graïke

- Sacred Band of Thebes

- List of traditional Greek place names

- Theban pederasty

Notes

References

- "Απογραφή Πληθυσμού - Κατοικιών 2011. ΜΟΝΙΜΟΣ Πληθυσμός" (in Greek). Hellenic Statistical Authority.

- Θῆβαι. Liddell, Henry George; Scott, Robert; A Greek–English Lexicon at the Perseus Project.

- "Population & housing census 2001 (incl. area and average elevation)" (PDF) (in Greek). National Statistical Service of Greece.

- "Kallikratis law" (PDF) (in Greek). Greek Ministry of the Interior. August 11, 2010. Retrieved June 8, 2014.

- Raymoure, K.A. "Thebes". Minoan Linear A & Mycenaean Linear B. Deaditerranean. "The Linear B word te-qa-ja". Palaeolexicon. Word study tool for ancient languages. "KN 5864 Ap (103)". "PY 539 Ep + fr. + fr. + fr. (1)". "TH 65 Wu (γ)". "MY 508 X (unknown)". "TH 140 Ft (312)". DĀMOS: Database of Mycenaean at Oslo. University of Oslo.

- Θήβασδε. Liddell, Henry George; Scott, Robert; An Intermediate Greek–English Lexicon at the Perseus Project.

- Palaima, Thomas G. (2004). "Sacrificial Feasting in the Linear B documents" (PDF). Hesperia. 73 (2): 217–246. doi:10.2972/hesp.2004.73.2.217.

- Herodotus Bibliography VII:204 ,222,223.

- Alexander the Great. Encyclopædia Britannica.

- Plutarch. Phocion. p. 17.

- Siculus, Diodorus. "Book XIX, 54". Bibliotheca historica.

- Plutarch's Lives, Volume III, Life of Alexander, Chapter 13

- "The Parian Marble". The Ashmolean Museum. Archived from the original on 18 July 2017.

- Beckett, Universal Biography, Vol. 1” p. 688

- Thirlwall, The History of Greece, Vol. 2” p. 325

Bibliography

- Herodotus – Histories

- Angold, Michael (1984) – The Byzantine Empire, 1025–1204

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Thebes, Greece. |

- Timeless Myths – House of Thebes

- Fossey, J.; J. Morin; G. Reger; R. Talbert; T. Elliott; S. Gillies. "Places: 541138 (Thebai/Thebae)". Pleiades. Retrieved March 8, 2012.

%2C_a_Stunning_Depiction_of_Dionysos.jpg)