Nordic race

The Nordic race is one of the putative sub-races into which some late-19th to mid-20th century anthropologists divided the Caucasian race. People of the Nordic type are mostly found in Northwestern Europe and Northern Europe,[1][2][3][4] particularly among populations in the areas surrounding the Baltic Sea, such as Balts, Germanic peoples, Baltic Finns and certain Celts and Slavs.[5][6] The physical traits of the Nordics were described as light eyes, light skin, tall stature, and dolichocephalic skull; the psychological traits as truthful, equitable, competitive, naive, reserved, and individualistic.[7] Other supposed sub-races were the Alpine race, Dinaric race, Iranid race, East Baltic race, and the Mediterranean race. In the early 20th century, beliefs that the Nordic race constituted the superior branch of the Caucasian race gave rise to the ideology of Nordicism.

Background

The Russian-born French anthropologist Joseph Deniker initially proposed "nordique" (meaning simply "northern") as an "ethnic group" (a term that he coined). He defined nordique by a set of physical characteristics: the concurrence of somewhat wavy hair, light eyes, reddish skin, tall stature and a dolichocephalic skull.[8] Of six 'Caucasian' groups Deniker accommodated four into secondary ethnic groups, all of which he considered intermediate to the Nordic: Northwestern, Sub-Nordic, Vistula and Sub-Adriatic, respectively.[9][10]

The notion of a distinct northern European race was also rejected by several anthropologists on craniometric grounds. German anthropologist Rudolf Virchow attacked the claim following a study of craniometry, which gave surprising results according to contemporary scientific racist theories on the "Aryan race." During the 1885 Anthropology Congress in Karlsruhe, Virchow denounced the "Nordic mysticism," while Josef Kollmann, a collaborator of Virchow, stated that the people of Europe, be they German, Italian, English or French, belonged to a "mixture of various races," furthermore declaring that the "results of craniology" led to "struggle against any theory concerning the superiority of this or that European race".[11]

Ripley (1899)

American economist William Z. Ripley purported to define a "Teutonic race" in his book The Races of Europe (1899).[12] He divided Europeans into three main subcategories: Teutonic (teutonisch), Alpine and Mediterranean. According to Ripley the "Teutonic race" resided in Scandinavia, northern France, northern Germany, the Baltic states and East Prussia, northern Poland, northwest Russia, Great Britain, Ireland, and parts of Central and Eastern Europe, and was typified by light hair, light skin, blue eyes, tall stature, a narrow nose, and slender body type. It was Ripley who popularized this idea of three biological European races. Ripley borrowed Deniker's terminology of Nordic (he had previously used the term "Teuton"); his division of the European races relied on a variety of anthropometric measurements, but focused especially on their cephalic index and stature.

Compared to Deniker, Ripley advocated a simplified racial view and proposed a single Teutonic race linked to geographic areas where Nordic-like characteristics predominate, and contrasted these areas to the boundaries of two other types, Alpine and Mediterranean, thus reducing the 'caucasoid branch of humanity' to three distinct groups.[13]

Early 20th century theories

By 1902 the German archaeologist Gustaf Kossinna identified the original Aryans (Proto-Indo-Europeans) with the north German Corded Ware culture, an argument that gained in currency over the following two decades. He placed the Indo-European Urheimat in Schleswig-Holstein, arguing that they had expanded across Europe from there.[14] By the early 20th century this theory was well established, though far from universally accepted. Sociologists were soon using the concept of a "blond race" to model the migrations of the supposedly more entrepreneurial and innovative components of European populations.

By the early 20th century, Ripley's tripartite Nordic/Alpine/Mediterranean model was well established. Most 19th century race-theorists like Arthur de Gobineau, Otto Ammon, Georges Vacher de Lapouge and Houston Stewart Chamberlain preferred to speak of "Aryans," "Teutons," and "Indo-Europeans" instead of "Nordic Race". The British German racialist Houston Stewart Chamberlain considered the Nordic race to be made up of Celtic and Germanic peoples, as well as some Slavs. Chamberlain called those people Celt-Germanic peoples, and his ideas would influence the ideology of Nordicism and Nazism.

Madison Grant, in his 1916 book The Passing of the Great Race, took up Ripley's classification. He described a "Nordic" or "Baltic" type:

"long skulled, very tall, fair skinned, with blond, brown or red hair and light coloured eyes. The Nordics inhabit the countries around the North and Baltic Seas and include not only the great Scandinavian and Teutonic groups, but also other early peoples who first appear in southern Europe and in Asia as representatives of Aryan language and culture."[15]

According to Grant, the "Alpine race", shorter in stature, darker in colouring, with a rounder head, predominated in Central and Eastern Europe through to Turkey and the Eurasian steppes of Central Asia and Southern Russia. The "Mediterranean race", with dark hair and eyes, aquiline nose, swarthy complexion, moderate-to-short stature, and moderate or long skull was said to be prevalent in Southern Europe, the Middle East, and North Africa.[16][17]

Only in the 1920s did a strong partiality for "Nordic" begin to reveal itself, and for a while the term was used almost interchangeably with Aryan.[18] Later, however, Nordic would not be co-terminous with Aryan, Indo-European or Germanic.[19] For example, the later Nazi minister for Food, Richard Walther Darré, who had developed a concept of the German peasantry as a Nordic race, used the term 'Aryan' to refer to the tribes of the Iranian plains.[19]

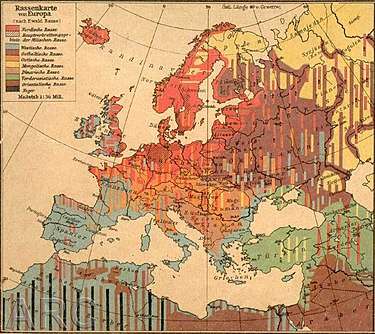

In Rassenkunde des deutschen Volkes (Racial Science of the German People), published 1922, Hans F. K. Günther identified five principal European races instead of three, adding the East Baltic race (related to the Alpine race) and Dinaric race (related to the Nordic race) to Ripley's categories. This work was influential in Ewald Banse's publication of Die Rassenkarte von Europa in 1925 which combined research by Deniker, Ripley, Grant, Otto Hauser, Günther, Eugen Fischer and Gustav Kraitschek.[20]

Coon (1939)

Carleton Coon in his book of 1939 The Races of Europe subdivided the Nordic race into three main types, "Corded", "Danubian" and "Keltic", besides a "Neo-Danubian" type[21] and a variety of Nordic types altered by Upper Palaeolithic or Alpine admixture.[22][23][24] "Exotic Nordics" are morphologically Nordic types that occur in places distant from the northwestern European center of Nordic concentration.[25]

Coon takes the Nordics to be a partially depigmented branch of the greater Mediterranean racial stock.[26] This theory was also supported by Coon's mentor Earnest Albert Hooton, who in the same year published Twilight of Man, which notes: "The Nordic race is certainly a depigmented offshoot from the basic long-headed Mediterranean stock. It deserves separate racial classification only because its blond hair (ash or golden), its pure blue or grey eyes".[27][26]

Coon suggests that the Nordic type emerged as a result of a mixture of "the Danubian Mediterranean strain with the later Corded element". Hence his two main Nordic types show Corded and Danubian predominance, respectively .[28] The third "Keltic" or "Hallstatt" type Coon takes to have emerged in the European Iron Age, in Central Europe, where it was subsequently mostly replaced, but "found a refuge in Sweden and in the eastern valleys of southern Norway."[29]

Coon further recognizes the following terminology of earlier authors:[30]

- Fenno-Nordic, "a hypothetical eastern branch of the Nordic race"

- Noric, "a blond, Dinaricized Nordic"

- Osterdal type, "the classic Iron Age Nordic, as found today in the eastern valleys of Norway"

- Sub-Nordic, "a racial group which would fall partly in the East Baltic and partly in the Neo-Danubian categories"

- Trønderlagen type or Trønder type, "a variety of Nordic with an excessive Corded element and Upper Palaeolithic mixture"

- Anglo-Saxon type, "a sub-type of Nordic which contains unreduced Upper Palaeolithic mixture"

Post-World War II theories

The depigmentation theory received notable support from later anthropologists, thus in 1947 Melville Jacobs noted: "To many physical anthropologists Nordic means a group with an especially high percentage of blondness, which represent a depigmentated Mediterranean".[31] In her work Races of Man (1963, 2nd Ed. 1965) Sonia Mary Cole went further to argue that the Nordic race belongs to the "brunette Mediterranean" Caucasoid division but that it differs only in its higher percentage of blonde hair and light eyes. The Harvard anthropologist Claude Alvin Villee, Jr. also was a notable proponent of this theory, writing: "The Nordic division, a partially depigmised branch of the Mediterranean group."[32] Collier's Encyclopedia as late as 1984 contains an entry for this theory, citing anthropological support.[33]

In his work The Races and Peoples of Europe (1977) the Swedish anthropologist Bertil Lundman introduced the term "Nordid" to describe the Nordic race, described as follows:

"The Nordid race is light-eyed, mostly rather light-haired, low-skulled and long-skulled (dolichocephalic), tall and slender, with more or less narrow face and narrow nose, and low frequency of blood type gene q. The Nordid race has several subraces. The most divergent is the Faelish subrace in western Germany and also in the interior of southwestern Norway. The Faelish subrace is broader of face and form. So is the North-Atlantid subrace (the North-Occidental race of Deniker), which is like the primary type, but has much darker hair. Above all in the oceanic parts of Great Britain the North-Atlantic subrace is also very high in blood type gene r and low in blood type gene p. The major type with distribution particularly in Scandinavia is here termed the Scandid or Scando-Nordid subrace."

Some forensic scientists, pathologists and anthropologists up to the 1990s continued to use the tripartite division of Caucasoids: Nordic, Alpine and Mediterranean, based on their cranial anthropometry. The anthropologist Wilton M. Krogman for example identified Nordic racial crania in his work "The Human Skeleton in Forensic Medicine" (1986) as being "dolichochranic".[34]

A 1990s study by Ulrich Mueller found that depigmentation of Nordic peoples around the Baltic Sea likely occurred due to vitamin D deficiency amongst peoples living there 10,000-30,000 years ago who had a lack of access to vitamin D foods such as dairy products at the time. Depigmentation allowed greater amount of ultraviolet B light to be absorbed through the skin to produce vitamin D.[35]

See also

- Aryan race

- Genetic history of Europe

- Germanic peoples

- The Race Question

- White Anglo-Saxon Protestant

References

Notes

- Hutton, Christopher (2005). Race and the Third Reich: Linguistics, Racial Anthropology and Genetics in the Dialectic of Volk. Polity. p. 133. Retrieved 4 April 2020.

- Hayes, Patrick J. (2012). The Making of Modern Immigration: An Encyclopedia of People and Ideas. ABC-CLIO. ISBN 9780313392030.

- Porterfield, Austin Larimore (1953). Wait the Withering Rain?. Leo Potishman Foundation. Retrieved 15 April 2015.

- Hutton, Christopher (2005). Race and the Third Reich: Linguistics, Racial Anthropology and Genetics in the Dialectic of Volk. Polity. ISBN 9780745631776. Retrieved 15 April 2015.

- File:Passing of the Great Race - Map 4.jpg

- Grant, Madison (1921) The Passing of the Great Race, New York: Scribner's Sons. p.167

- Gunther, Hans F. K., The Racial Elements of European History, translated by G. C. Wheeler, Methuen & Co. LTD, London, 1927, p. 3

- "Deniker, J., The Races of Man". nordish.net. Archived from the original on 1 May 2008. Retrieved 22 October 2017.

- Deniker, J. - Les Races de l'Europe (1899);The Races of Man (London: Walter Scott Ltd., 1900);Les Races et les Peuples de la Terre (Masson et Cie, Paris, 1926)

- Deniker (J.) "Essai d'une classification des races humaines, basée uniquement sur les caractères physiques". Bulletins de la Société d'anthropologie de Paris. Volume 12 Numéro 12. 1889. pp. 320-336.

- Andrea Orsucci, "Ariani, indogermani, stirpi mediterranee: aspetti del dibattito sulle razze europee (1870–1914) Archived 2012-12-18 at Archive.today, Cromohs, 1998 (in Italian)

- William Z. Ripley, in The Races of Europe: A Sociological Study (New York: D. Appleton and Co., 1899)

- J.G. (1899). "review of The Races of Europe by William Z. Ripley". The Journal of the Anthropological Institute of Great Britain and Ireland. 29 (1/2): 188–189.

- Arvidsson, Stefan (2006). Aryan Idols. USA: University of Chicago Press. p. 143. ISBN 978-0-226-02860-6.

- Madison Grant, "The Passing of the Great Race", Scribner's Sons, 1921, p. 167

- John Higham (2002). Strangers in the Land: Patterns of American Nativism, 1860–1925. Rutgers University Press. p. 273. ISBN 978-0-8135-3123-6.

- Bryan S Turner (1998). The Early Sociology of Class. Taylor & Francis. p. 241. ISBN 978-0-415-16723-9.

- Field, Geoffrey G. (1977). "Nordic Racism". Journal of the History of Ideas. 38 (3): 523–40. doi:10.2307/2708681. ISSN 1086-3222. JSTOR 2708681.

- Anna Bramwell. 1985. Blood and Soil: Richard Walther Darré and Hitler's "Green Party". Abbotsbrook, England: The Kensal Press. ISBN 0-946041-33-4, p. 39&40

- Gunther, Hans F. K., The Racial Elements of European History, translated by G. C. Wheeler, Methuen & Co. LTD, London, 1927

- "de-Corded Nordic (and hence Danubian) prototype brachycephalized by Ladogan admixture." Plate 31: Neo-Danubians Archived 2010-05-14 at the Wayback Machine

- "Plate 32: Nordics Altered by Northwestern European Upper Palaeolithic Mixture: I". altervista.org. Archived from the original on 1 September 2010. Retrieved 22 October 2017.

- "Plate 33: Nordics Altered by Northwestern European Upper Palaeolithic Mixture: II". altervista.org. Archived from the original on 1 September 2010. Retrieved 22 October 2017.

- "Plate 34: Nordics Altered by Mixture with Southwestern Borreby and Alpine Elements". altervista.org. Archived from the original on 1 September 2010. Retrieved 22 October 2017.

- examples from eastern Russia, Albania, Portugal and North Africa; Plate 30: Exotic Nordics Archived 2010-05-14 at the Wayback Machine

- Melville Jacobs, Bernhard Joseph Stern. General anthropology. Barnes & Noble, 1963. P. 57.

- Twilight of Man, Earnest Albert Hooton, G. P. Putnam's Sons, 1939 p. 77.

- "Plate 27: The Nordic Race: Examples of Corded Predominance". altervista.org. Archived from the original on 14 April 2010. Retrieved 22 October 2017.

- "The Nordic Race: Hallstatt and Keltic Iron Age Types". altervista.org. Archived from the original on 1 September 2010. Retrieved 22 October 2017.

- "Coon (1939), "Appendix II.: Glossary"". altervista.org. Archived from the original on 1 October 2010. Retrieved 22 October 2017.

- Outline of Physical Anthropology, 1947, p. 49.

- Biology, 1972, Saunders, p. 786.

- Collier's Encyclopedia, Vol. 9, William Darrach Halsey, Emanuel Friedman, Macmillan Educational Co., 1984, p. 412.

- "The Human Skeleton in Forensic Medicine", Wilton Marion Krogman, M. Yaşar İşcan, C.C. Thomas, 1986, p. 270, p. 489.

- R. Hegselmann, Ulrich Mueller, Klaus G. Troitzsch. Modelling and Simulation in the Social Sciences from the Philosophy of Science Point of View. Dordrecht, Netherlands: Kluwer Academic Publishers, 1996. Pp. 118-

External links

- Examples of Nordics (plates 27-30 and 32-34) from Carleton Coon's The Races of Europe