Scaenae frons

The scaenae frons is the elaborately decorated permanent architectural background of a Roman theatre stage. The form may have been intended to resemble the facades of imperial palaces. It could support a permanent roof or awnings. The Roman scaenae frons was also used both as the backdrop to the stage and behind as the actors' dressing room. Largely through reconstruction or restoration, there are a number of well-preserved examples.

.jpg)

Description

The scaenae frons is the elaborately decorated permanent architectural background of a Roman theatre stage. Normally there are three entrances to the stage (Palmyra has five) including a grand central entrance, known as the porta regia or "royal door". The form may have been intended to resemble the facades of imperial palaces.[1] The scaenae frons is often two and sometimes three stories in height and was central to the theatre's visual impact for this was what was seen by a Roman audience at all times. Tiers or balconies were supported by an exuberant display of columns, normally in the Corinthian order, often originally including many statues in niches.[2] A siparium was stretched on the scaenae frons.

In smaller theatres it could support a permanent roof, enclosing the whole theatre, and in larger ones awnings over the whole or parts of the theatre, perhaps secured to masts rising above it, for which there is some evidence.[3]

This form was influenced by Greek theatre, which had an equivalent but simpler skene building (meaning "tent", showing the original nature of it). This led to the stage or space before the skene being called the proscenium. In the Hellenistic period the skene became more elaborate, perhaps with columns, but also used to support painted scenery.[4]

The Roman scaenae frons was also used both as the backdrop to the stage and behind as the actors' dressing room. It no longer supported painted sets in the Greek manner but relied for effect on elaborate permanent architectural decoration. This achieved a Baroque effect also seen in large nymphaea and library facades, often with an undulating facade, pushing forward and then retreating.[5] All the significant examples date from the Imperial period; the Theatre of Pompey in Rome, completed in 55 BC, was the first stone theatre and probably launched the style.[3]

An inscription in the entablature above the lowest columns often recorded the emperor and others who had helped to fund the construction. A feature often found in the Western Empire, but less so in the Greek-speaking areas, was the row of curved recesses in the face of the front of the stage, as at Sabratha and Leptis Magna.[6]

Renaissance

The roofed Renaissance Teatro Olimpico ("Olympic Theatre") in Vicenza, northern Italy (1580–1585, designed by Andrea Palladio) includes a fully decorated scaenae frons and gives a good general impression of what the Roman ones would have looked like in their original state, though it is in stucco over a wood framework. The theatre is also famous for the trompe-l'œil scenery, designed by Vincenzo Scamozzi, behind the scaenae frons, which gives the appearance of long streets receding to a distant horizon; it is not clear how much this reflects ancient practice. This was intended to be temporary in 1585, but remains in excellent condition.

Surviving examples

Some well-preserved examples (mostly including some restoration or reconstruction) include:

| City (Roman name) |

City (modern name) |

Country | Coordinates | Notes References |

Photographs |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

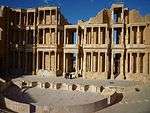

| Sabratha | Sabratha | Libya | 32.805371°N 12.485165°E | Restored theatre at Sabratha before WW2, now "the most illuminating preserved example of the scaenae frons".[7] |  |

| Emerita Augusta | Mérida | Spain | 38.915346°N 6.338643°W | Theatre of Emerita Augusta |  |

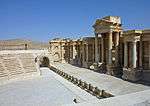

| Palmyra | Syria | 34.550768°N 38.268761°E | Roman Theatre at Palmyra |  | |

| Gerasa (1 of 2) | Jerash | Jordan | 32.276789°N 35.889155°E | ||

| Gerasa (2 of 2) | Jerash | Jordan | 32.282604°N 35.892341°E | ||

| Philippopolis | Plovdiv | Bulgaria | 42.14678°N 24.75094°E | Plovdiv Roman theatre |  |

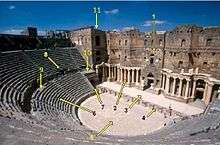

| Bostra | Bosra | Syria | 32.517650°N 36.481426°E | Roman Theatre at Bosra, see also photo above |  |

| Leptis Magna | Khoms | Libya | 32.638399°N 14.290620°E |  | |

| Aspendos | Serik, Antalya | Turkey | 36.938944°N 31.172296°E | Overall probably the best preserved Roman theatre, but the scaenae frons has lost its decoration, including many statues. |  |

| Aurasio | Orange | France | 44.13587°N 4.80886°E | The Roman theatre of Orange is a UNESCO World Heritage Site, together with other Roman buildings of the city. Stripped of its decoration. |  |

| Acinipo | Spain | 36.831855°N 5.240466°W | |||

| Volaterrae | Volterra | Italy | 43.403611°N 10.86°E |  |

See also

Notes

- Boardman, 262-263

- Henig, 57; Wheeler, 116

- Wheeler, 116; Boardman, 262

- Boardman, 1676-168

- Henig, 57; Boardman, 167-168

- Henig, 57-58

- Boardman, 262

References

- Henig, Martin (ed), A Handbook of Roman Art, Phaidon, 1983, ISBN 0714822140

- Wheeler, Mortimer, Roman Art and Architecture, 1964, Thames and Hudson (World of Art), ISBN 0500200211

- Boardman, John ed., The Oxford History of Classical Art, 1993, OUP, ISBN 0198143869

External links

- On issues relating to the use of the term "scaenae frons" see :

- The discovery of Villa P. Fannius Synistor and the scaenarum frontes - scaenae frons conundrum

- La découverte de la villa di P. Fannius Synistor and le casse-tête du scaenae frontes – scaenae frons