Tensas Parish, Louisiana

Tensas Parish (French: Paroisse des Tensas) is a parish located in the northeastern section of the State of Louisiana; its eastern border is the Mississippi River. As of the 2010 census, the population was 5,252.[1] It is the least populated parish in Louisiana. The parish seat is St. Joseph.[2] The name Tensas is derived from the historic indigenous Taensa people.[3] The parish was founded in 1843 following Indian Removal.[4]

Tensas Parish | |

|---|---|

Parish | |

| Parish of Tensas | |

Tensas Parish Courthouse at St. Joseph | |

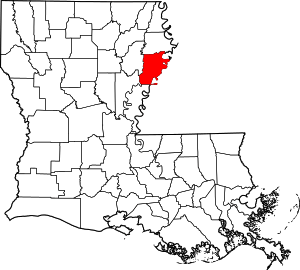

Location within the U.S. state of Louisiana | |

Louisiana's location within the U.S. | |

| Coordinates: 32°00′N 91°20′W | |

| Country | |

| State | |

| Founded | March 17, 1843 |

| Named for | Taensa people |

| Seat | St. Joseph |

| Largest town | Newellton |

| Area | |

| • Total | 641 sq mi (1,660 km2) |

| • Land | 603 sq mi (1,560 km2) |

| • Water | 38 sq mi (100 km2) 6.0% |

| Population (2010) | |

| • Total | 5,252 |

| • Estimate (2018) | 4,462 |

| • Density | 8.2/sq mi (3.2/km2) |

| Time zone | UTC−6 (Central) |

| • Summer (DST) | UTC−5 (CDT) |

| Congressional district | 5th |

| Website | louisiana |

The parish was developed for cotton agriculture, which dominated the economy through the early 20th century. There has also been some cattle ranching in the 1930s and timber extraction.

History

Pre-history

Tensas Parish was the home to many successive indigenous groups in the thousands of years before European settlements began. Some village and mound sites once built by these various peoples are preserved today as archaeological sites.

One example is the Flowery Mound, a rectangular platform mound just east of St. Joseph. It measures 10 feet (3.0 m) in height and 165 feet (50 m) by 130 feet (40 m) at its base; the summit measures 50 feet (15 m) square. Core samples taken during investigations at the site have revealed the mound was built in a single stage. Because the fill types can still be differentiated, the mound is thought to be relatively young. Radiocarbon dating of charcoal found in a midden under the mound reveals that the site was occupied from 996–1162 during the Coles Creek period. The mound was built over the midden between 1200–1541 during the Plaquemine/Mississippian culture period.[5] The corners of the mound are oriented in the four cardinal directions.[6] Related ancient sites include Balmoral Mounds, Ghost Site Mounds, and Sundown Mounds.

Historic tribes in this area were the Choctaw and Natchez, in addition to smaller groups such as the Taensa people.

Antebellum development

Following Indian Removal by the United States government in the 1830s, the land was sold and this area was developed by European Americans for cotton plantations, the leading commodity crop before the Civil War. Planters moved into the area from the eastern and upper South, either bringing or purchasing numerous enslaved African Americans as workers. They developed plantations along the river and Lake St. Joseph, as waterways were required for transportation routes and access to markets. In 1861, according to the United States Coast Survey map, 90.8% of the parish's inhabitants were slaves.[7]

Civil War and Reconstruction

During the American Civil War, the Confederacy relied on wealthy private citizens, particularly planters, organized, equipped, and transported military companies. In Tensas Parish, cotton planter A. C. Watson provided one company of artillery with more than $40,000.[8]

In April 1862, Governor Thomas Overton Moore, reconciled to the fall of New Orleans, ordered the destruction of all cotton in those areas in danger of occupation by Union forces. Along the levees and atop Indian mounds in Tensas Parish, slaves were directed to burn thousands of bales of cotton, which took days to accomplish.[9] At the time, Tensas Parish was second only to Carroll Parish (later divided into East and West Carroll) in the overall production of cotton in Louisiana.[10]

Near Newellton is the Winter Quarters Plantation, where Union General Ulysses S. Grant and his men spent the winter of 1862–63. It has been designated as a state historic site and is being restored. In the spring and summer of 1863, Grant launched his campaign against Vicksburg, Mississippi, to the northeast of Tensas Parish.

In 1864, Captain Joseph C. Lea of the Missouri guerrillas, with two hundred men, invaded Tensas Parish and encountered a fortification held by four hundred Union soldiers under the command of Colonel Alfred W. Eller. Lea inflicted heavy casualties and drove the men to the Mississippi River, where they boarded their boats. He seized a federal warehouse with gunpowder, groceries, and medical supplies. Facing attacks from the Union forces who tried to return to their fortification, Lea managed to secure seventy-five Federal wagons and cotton carts, all of which he dispatched to Shreveport.[11]

Franklin Plantation, owned by physician Allen T. Bowie, was considered the most elegant of the antebellum homes along Lake St. Joseph, an oxbow lake near Newellton. A Missouri Confederate wrote that the area was "unsurpassed in beauty and richness by any of the same extent... in the world."[12] Union officers in charge of the XIII and XVII Corps kept close watch on the troops to prevent looting as the men marched southward headed indirectly to Vicksburg. But when General William Tecumseh Sherman's XV Corps joined Grant's forces, however, the soldiers became lawless. On May 6, 1863, rowdies from General James Madison Tuttle's division burned most of the mansions that fronted Lake St. Joseph, including Franklin Plantation.[12]

Toward the end of the war, schools were established for African American children in northeastern Louisiana, including Tensas and Concordia parishes. Some were founded in local efforts and some through the sponsorship of the American Missionary Association.

According to historian John D. Winters of Louisiana Tech University, who has been criticized for the racial bias expressed in The Civil War in Louisiana (1963),[13] the students

ranged in age from four to forty, were poorly clothed, loved to fight, and were 'extremely filthy, their hair filled with vermin.' Religious instruction, with readings from the Bible and prayers, was emphasized while reading from primers and studying spelling and writing rounded out the course work. The program stressed 'a maximum of memory and a minimum of reasoning.' The schools sponsored by the Christian societies were gradually taken over by a board of education and supported by special property and crop taxes. These schools operated primarily along the Mississippi River and few, if any, were established in the interior [of Louisiana].[14]

During and after the Reconstruction era, white Democrats acted to suppress black and Republican voting in the state and in this parish with its large black majority. They enforced Jim Crow laws and rules through intimidation and violence, including lynchings.

From 1877 to 1950, there were 30 lynchings of blacks in Tensas Parish, most in the decades around the turn of the 20th century; Tensas was among the four parishes in Louisiana with the highest number of lynchings in this period, and Louisiana was among the states with the highest number of such murders.[15]

But from 1878 through 1920, the Mississippi Delta area of northern Louisiana legally executed more blacks than did any other part of the state, after they had been convicted by all-white juries. For instance, between 1880 and 1920, twelve persons were executed in Tensas Parish, at least seven of them black.[16]

20th century to present

By the turn of the 20th century, the parish seat of St. Joseph had 720 residents. Tensas Parish had 19,070. Most of the population was still engaged in cotton agriculture, where numerous African Americans worked as sharecroppers and tenant farmers. Others worked in trades associated with river traffic.

While mechanization was gradually introduced, blacks left Tensas Parish before its full effects had taken place, to escape the violence of lynchings and executions. In the 1900 census Tensas Parish had 17,839 African Americans (94 percent) and 1,231 whites (6 percent). By 1920, the number of African Americans had declined by 42% to 10,314 (making up 85 percent of the parish population). Whites numbered 1771 (15 percent).

Twenty years later, by 1940, the number of blacks in the parish had risen only to 11,194 (70 percent) while the whites had increased markedly to 4,746 (30 percent). These differences likely reflected a continuing outmigration by blacks, as well as in-migration of whites from other areas, who settled in the hill country during the 1920s-1930s.[17] Both blacks and whites left the parish to move to defense industry jobs on the West Coast during and after World War II.

In 1962, when only whites could vote, Tensas Parish gave Republican Taylor W. O'Hearn 48.2 percent of the vote in a race for the U.S. Senate against powerful incumbent Democrat Russell B. Long. Long overwhelmingly defeated O'Hearn statewide.

Prior to January 1964, when fifteen African Americans were permitted to register, there had been no black voters on the Tensas Parish rolls since the state passed a constitution in 1898 to disenfranchise blacks. In 1964 the parish consisted of 7,000 blacks and 4,000 whites. Whites had controlled the political system since the late 19th century and excluded blacks from the political system for more than 60 years. Tensas was the last of Louisiana's parishes in the 20th century to allow African Americans to register to vote.

In the fall of 1964 O'Hearn was elected to an at-large seat from Caddo Parish as a state representative from Shreveport. Another white Republican was also elected from Caddo Parish, as were three Democrats, all running for at-large seats. In 1964 Tensas Parish, with mostly only conservative whites voting, supported Republican presidential nominee Barry M. Goldwater rather than incumbent Democrat President Lyndon B. Johnson, who was supporting civil rights. Few of the parish's thousands of black residents were yet enabled to vote.

After the passage of the Voting Rights Act of 1965, large numbers of Tensas Parish blacks began registering to vote. These new black voters were staunchly Democratic, as the national party had supported their drive for civil rights. Since then, the black majority of the parish has made it a Democratic stronghold. Some white Democrats have been elected to public offices in the parish, including Sheriff Rickey A. Jones and several school board members.

In November 2019, Alex "Chip" Watson, Jr., who is African American, was elected to the District 1 police jury seat. Watson defeated incumbent Larry W. Foster, who is white and the police jury president, and challenger "Johnny" Daves, who is also white. With Watson's victory, the Tensas Parish Police Jury will be majority African American for the first time in the parish's history.

Tensas Parish was de jure desegregated until the fall of 1970. Although the state officially desegregated, the schools are largely de facto segregated, as many white parents have sent their children to private academies founded at that time. The majority of white students attend the private Tensas Academy in St. Joseph. Nearly all African-American pupils attend the public schools, where few whites are registered.

Enrollment in the public system, now based in St. Joseph, has declined in recent years as parish population has declined.[18] The former Newellton High School in Newellton and Waterproof High School and Lisbon Elementary School in Waterproof have closed because of decreased enrollments. Tensas High School in St. Joseph was consolidated in 2006 from the former Joseph Moore Davidson High School of St. Joseph, as well as Newellton and Waterproof high schools.

In May 2010, the graduating class of forty students at Tensas High School included three whites. Ten white students graduated from Tensas Academy, and four whites from the private Newellton Christian Academy.[19]

Partisan politics

Historically, Tensas Parish has been heavily Democratic in orientation, although the make-up of the party has changed markedly in terms of demographics.

In the 1860 presidential election, the parish supported by plurality the Constitutional Union Party candidate, U.S. Senator John Bell of Tennessee, who pledged to support the Constitution of the United States, the Union of states, and the "enforcement of the laws." Louisiana as a whole narrowly cast its electoral votes for the Southern Democratic choice, Vice President John C. Breckinridge of Kentucky. Regular Democratic nominee Stephen A. Douglas of Illinois ran poorly in Louisiana, and the Republican candidate, Abraham Lincoln, also of Illinois, was not even listed on the state ballot.[20]

The end of the war was followed by emancipation of millions of enslaved African Americans in the South. After gaining the franchise, most black men joined the Republican Party, electing candidates who made up a biracial legislature in Louisiana during Reconstruction. White Democratic groups worked through intimidation and fraud to suppress black and white Republican voting during and after the Reconstruction era. In 1898 Louisiana passed a new state constitution with provisions that created barriers to voter registration in order to disenfranchise African-American voters and cripple the Republican Party. Louisiana was effectively a one-party state and part of the Solid South for the next several decades.

In 1988, Vice President George H.W. Bush, the Republican presidential nominee, prevailed in Tensas Parish with 1,645 votes (50 percent). Governor Michael Dukakis of Massachusetts trailed with 1,556 (47.3 percent).[21]

In 1996, native son of the South U.S. President Bill Clinton obtained 1,882 votes (60.7 percent) in Tensas Parish, and the Republican Bob Dole of Kansas polled 1,000 votes (32.3 percent).[22]

In 2000, the Democratic nominee, Vice President Al Gore, won Tensas Parish by 250 votes. The Democratic electors polled 1,580 votes that year to 1,330 for the George W. Bush-Dick Cheney ticket.[23] In 2004, the Democratic ticket of U.S. Senators John F. Kerry of Massachusetts and John Edwards of North Carolina carried Tensas Parish, 1,460 (49.6 percent) to 1,453 (49 percent) for Bush-Cheney.[24]

In the 2008 presidential contest, Democratic nominee Barack Obama of Illinois won Tensas Parish, 1,646 (54.1 percent) to 1,367 (45 percent) for Republican Senator John McCain of Arizona.[25] In 2012, President Obama again carried the parish, with 1,564 votes (55.6 percent), while rival Mitt Romney polled 1,230 votes (43.7 percent).[26] The Obama-McCain and Obama-Romney voter divisions in 2008 and 2012 reflect the demographics of the political parties in Tensas Parish.

In the 2004 U.S. Senate primary election, Tensas Parish gave a plurality to the Republican candidate, U.S. Representative David Vitter of St. Tammany Parish, who polled 1,145 votes (41 percent) compared to 881 ballots (32 percent) for his chief Democratic rival, Congressman Chris John of Crowley. He won statewide. There was no general election in Tensas Parish to determine if Vitter would have surpassed 50 percent plus one vote to obtain an outright majority in this traditionally Democratic parish.[24]

In 2007, the successful Republican gubernatorial candidate, U.S. Representative Bobby Jindal, polled 40 percent in Tensas Parish. Tensas gave a plurality of 48 percent to Secretary of State Democrat Jay Dardenne. Two Republican candidates ran for a seat on the Tensas Parish Police Jury, the parish governing body, and Emmett L. Adams, Jr., won over fellow Republican Patrick Glass, 207-179 votes (54-46 percent).[27]

Under the state constitution, prior to 1968, each parish -regardless of population- elected at least one member to the Louisiana House of Representatives. That year the US Supreme Court ruled that states had to develop legislative districts that were based on roughly equal populations and had to be redistricted after each decennial census, based on the principle of "one man, one vote". It said there was no constitutional basis for state legislatures to be based on geographical districts (such as one representative per parish), as that system had resulted in inequities: particularly marked under-representation of more populated, urbanized areas and an unequal dominance of state legislatures by rural areas. Louisiana and numerous other states had not regularly conducted redistricting, although there had been dramatic population shifts since the turn of the 20th century.

The last member to represent only Tensas Parish was Democrat S. S. DeWitt of Newellton and later St. Joseph. DeWitt won the legislative post in 1964 by unseating 20-year incumbent J.C. Seaman of Waterproof. Because of Tensas Parish's small population, the state house district was made to include part of Franklin Parish. In the 1971 primary, DeWitt lost the seat to Lantz Womack of Winnsboro in Franklin Parish.

Geography

According to the U.S. Census Bureau, the parish has a total area of 641 square miles (1,660 km2), of which 603 square miles (1,560 km2) is land and 38 square miles (98 km2) (6.0%) is water.[28]

The parish seat of St. Joseph is located adjacent to the Mississippi River levee system, which protects the eastern border of the parish along the river.

The developed Lake Bruin State Park lies near St. Joseph. Lake Bruin is an oxbow lake created by the meandering of the Mississippi River; there are two other oxbow lakes in the parish.

Adjacent parishes and counties

- Madison Parish (north)

- Warren County, Mississippi (northeast)

- Claiborne County, Mississippi (east)

- Jefferson County, Mississippi (east)

- Adams County, Mississippi (southeast)

- Concordia Parish (south)

- Catahoula Parish (southwest)

- Franklin Parish (west)

Communities

The largely rural parish has three communities: Newellton, St. Joseph, and Waterproof. Newellton was founded by the planter and attorney John David Stokes Newell, Sr., who named it for his father Edward D. Newell, a native of North Carolina. Tensas Parish has one principal cemetery, Legion Memorial, established in 1943 and located just north of Newellton. A new entrance sign to the cemetery has been erected.

All three communities are linked by Highway 65, which passes just to the west of each town.

Major highways

National protected area

Demographics

The mostly rural parish has continued to lose population. Between July 1, 2006, and July 1, 2007, Tensas Parish lost 173 residents, or 2.9 percent of its population. Police Jury Vice President Jane Merriett Netterville, a Democrat from St. Joseph,[29] expressed surprise at those figures, as a number of people had moved into the parish in 2005 and 2006 as refugees from New Orleans and coastal areas after Hurricane Katrina. "Maybe the loss was the people who died. We have a large elderly population," she told the Baton Rouge Morning Advocate. Netterville explained that younger people leave Tensas Parish because of the scarcity of higher-paying jobs.[30]

| Historical population | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Census | Pop. | %± | |

| 1850 | 9,040 | — | |

| 1860 | 16,078 | 77.9% | |

| 1870 | 12,419 | −22.8% | |

| 1880 | 17,815 | 43.4% | |

| 1890 | 16,647 | −6.6% | |

| 1900 | 19,070 | 14.6% | |

| 1910 | 17,060 | −10.5% | |

| 1920 | 12,085 | −29.2% | |

| 1930 | 15,096 | 24.9% | |

| 1940 | 15,940 | 5.6% | |

| 1950 | 13,209 | −17.1% | |

| 1960 | 11,796 | −10.7% | |

| 1970 | 9,732 | −17.5% | |

| 1980 | 8,525 | −12.4% | |

| 1990 | 7,103 | −16.7% | |

| 2000 | 6,618 | −6.8% | |

| 2010 | 5,252 | −20.6% | |

| Est. 2018 | 4,460 | [31] | −15.1% |

| U.S. Decennial Census[32] 1790-1960[33] 1900-1990[34] 1990-2000[35] 2010-2013[1] | |||

As of the 2010 United States Census, there were 5,252 people living in the county. 56.5% were Black or African American, 41.9% White, 0.2% Asian, 0.1% Native American, 0.5% of some other race and 0.8% of two or more races. 1.2% were Hispanic or Latino (of any race).

As of the census of 2000, there were 6,618 people, 2,416 households, and 1,635 families living in the parish. The population density was 11 people per square mile (4/km2). There were 3,359 housing units at an average density of 6 per square mile (2/km2). The racial makeup of the parish was 55.6% Black or African American, 43.2% White, 0.1% Native American, 0.2% Asian, 0.29% from other races, and 0.9% from two or more races. 1.4% of the population were Hispanic or Latino of any race.

There were 2,416 households, out of which 30.00% had children under the age of 18 living with them, 43.10% were married couples living together, 20.20% had a female householder with no husband present, and 32.30% were non-families. 29.30% of all households were made up of individuals, and 14.90% had someone living alone who was 65 years of age or older. The average household size was 2.54 and the average family size was 3.14.

In the parish the population was spread out, with 26.50% under the age of 18, 10.00% from 18 to 24, 25.10% from 25 to 44, 22.90% from 45 to 64, and 15.50% who were 65 years of age or older. The median age was 37 years. For every 100 females there were 97.80 males. For every 100 females age 18 and over, there were 96.20 males.

The median income for a household in the parish was $19,799, and the median income for a family was $25,739. Males had a median income of $26,636 versus $16,781 for females. The per capita income for the parish was $12,622. About 30.00% of families and 36.30% of the population were below the poverty line, including 48.20% of those under age 18 and 29.60% of those age 65 or over.

Education

Public schools in Tensas Parish are operated by the elected seven-member Tensas Parish School Board.

Government

| Parish Administration | Administrators |

|---|---|

| Sheriff | Rickey A. Jones |

| Coroner | David McEacharn |

| Assessor | Donna R. Ratcliff |

| School Board Superintendent | Dr. Paul E. Nelson |

| Parish Police Jury | Police Jurors |

|---|---|

| District 1 | Alex "Chip" Watson, Jr. |

| District 2 | Terrence South |

| District 3 | Bill Crigler |

| District 4 | Billy Arceneaux |

| District 5 | Roderick "Rod" D. Webb (President) |

| District 6 | Bubba Rushing (Vice President) |

| District 7 | Robert Clark |

| 6th Judicial District | Parish Judicial Leaders |

|---|---|

| Judge of Division "A" | Michael E. Lancaster (Chief Judge) |

| Judge of Division "B" | Laurie R. Brister |

| District Attorney | James E. Paxton |

| Clerk of Court | Christina "Christy" C. Lee |

| Parish School Board | Board Members |

|---|---|

| District 1 | Jennifer Burnside |

| District 2 | Morgan Carter |

| District 3 | Patrick Joffrion |

| District 4 | Annice Miller (President) |

| District 5 | Esaw Turner |

| District 6 | Mary Nell Rushing |

| District 7 | John L. Turner (Vice President) |

The Tensas Gazette

Tensas Parish is served by a weekly newspaper, The Tensas Gazette, which began in 1871 under the title The North Louisiana Journal. It was renamed The Tensas Gazette in 1886. Some 1,300 copies are circulated each Wednesday throughout the parish.[36]

Josiah Scott (born 1874 in Vidalia) was reared by a maternal uncle who was the editor of the Concordia Sentinel. At the age of twenty, Scott took over The Tensas Gazette, then owned by Judge Hugh Tullis. In 1906, Scott purchased the paper from Tullis and continued as editor until his death in 1953. He was known for political commentary over the decades.[37]

Upon Scott's death, Paul Alexander Myers, Jr., and his wife, the former Patricia Wilds (1924-1999) purchased The Tensas Gazette and operated it together until his death in 1964. Thereafter until her retirement in 1988, Mrs. Myers owned and published the paper. From 1974 to 1988, she concurrently owned the Richland Beacon-News in Rayville, in Richland Parish. The daughter of Oliver Newton Myers (1900-1965) and the former Alice Robinson (1898-1948) of Natchez, Mississippi, Myers graduated from the former Joseph Moore Davidson High School in St. Joseph and the University of Alabama in Tuscaloosa. As a member of the Louisiana State Park Foundation Board, she was instrumental in the reopening of Winter Quarters State Historic Site south of Newellton. She was a member of the Tensas Development Board, the Tensas Garden Club, the Lake Bruin Country Club, and the Daughters of the American Revolution. In 1997, she was named "Citizen of the Year" by the St. Joseph chapter of Rotary International. The Myerses had four children: Paul Alexander "Andy" Myers, III, of Gulf Breeze, Florida, LaRue Myers Cooper of Dry Prong, Morris Newton Myers of Temecula in Riverside County, California, and Alice Robinson "Robin" Myers of St. Joseph, who is named for her maternal grandmother. A Roman Catholic, Mrs. Myers is interred at the Natchez City Cemetery.[38]

No longer under local ownership, The Tensas Gazette is now published by Louisiana State Newspapers, Inc.[39] After years in a downtown location, The Tensas Gazette moved to 118 Arts Drive near the new Tensas Parish Civic Center off U.S. Highway 65.

Communities

Towns

- Newellton

- St. Joseph (parish seat)

- Waterproof

Unincorporated communities

- Balmoral

- Crimea

- Helena

- Mayflower

- Somerset

- Yucatan Landing

Notable people

- Henry Watkins Allen, Confederate States of America general and Civil War governor of Louisiana, grew cotton in Tensas Parish near Newellton in the years prior to the war before he relocated to Baton Rouge and became a public figure.

- Ray R. Allen, municipal secretary-treasurer and finance director in Alexandria, Louisiana (1963–1979), graduated from Newellton High School (ca. 1937).

- Daniel F. Ashford (1879-1929), member of the Louisiana House of Representatives from 1916 until his death; planter, first person in Tensas Parish to own an automobile and a wristwatch.[40]

- Andrew Brimmer, the first African American appointed (by President Lyndon B. Johnson) to the Federal Reserve Board in Washington, D.C., was born in Tensas Parish.

- Clifford Cleveland Brooks, cotton planter; member of the Louisiana State Senate from 1924 to 1932[41]

- Sharon Renee Brown, Miss Louisiana USA 1961, Miss USA 1961, was Miss Waterproof that same year.

- Buddy Caldwell, district attorney from East Carroll, Madison, and Tensas parishes and thereafter attorney general of Louisiana, elected 2007.

- Claire Chennault of the "Flying Tigers," though born in Commerce, Texas, lived for a time in Waterproof in southern Tensas Parish.

- Elliot D. Coleman (1881–1963), sheriff of Tensas Parish from 1936–1960 and a bodyguard at the assassination of U.S. Senator Huey P. Long, Jr.

- George Henry Clinton, chemist, lawyer, member of both houses of the legislature from Tensas Parish.[42][43]

- Charles C. Cordill, Louisiana state senator from Tensas Parish from 1884 to 1912[43]

- Brenham C. Crothers (1905-1984), Ferriday cattleman who represented Tensas Parish in the Louisiana State Senate from 1948 to 1952 and again from 1956 to 1960[43]

- Joseph T. Curry (1895-1961), Louisiana state representative from Tensas Parish from 1930 to 1944[42]

- James Houston "Jimmie" Davis, singer, songwriter and governor; owned farm property in Tensas Parish.

- S. S. DeWitt, state representative from Tensas Parish from 1964 to 1972

- Sarah Dorsey, author and benefactor of Jefferson Davis

- Emmitt Douglas, president of the Louisiana NAACP from 1966–1981

- C. B. Forgotston (1945-2016), Hammond attorney, political activist, and state government watchdog

- Troyce Guice, a member of the Louisiana Levee Board and the Mississippi River Bridge Commission, twice a candidate for the U.S. Senate.

- Neal Lane "Lanny" Johnson, a former Tensas school superintendent and current superintendent in Winnsboro; Louisiana state representative (1976–1980).

- Howard M. Jones (1900-1980), state senator from Tensas Parish from 1960 to 1968.

- Samuel W. Martien (1854-1946), planter from Waterproof and member of the Louisiana House of Representatives from 1906 to 1920[44]

- James Albert Noe, Sr., former governor of Louisiana; once owned farm property in Tensas Parish.

- James E. Paxton, district attorney of East Carroll, Madison, and Tensas parishes; St. Joseph resident[45]

- Phil Preis, Baton Rouge attorney; gubernatorial candidate in 1995 and 1999

- Clyde V. Ratcliff, Louisiana state senator from 1944 to 1948 and planter in Newellton until his death in 1952[46]

- Dan Richey, former Louisiana State Senator who represented Tensas Parish

- J.C. Seaman, state representative from Tensas Parish from 1944–1964; promoter of Lake Bruin State Park

- Jefferson B. Snyder, district attorney for Tensas, Madison, and East Carroll parishes from 1904-1948[47]

- Robert H. Snyder, state representative from Tensas Parish from 1890–1896 and 1904–1906, Speaker of the Louisiana House of Representatives in the second term, died in office; Lieutenant governor from 1896–1900

- Garner H. Tullis, civic leader in New Orleans.[48]

- Thomas M. Wade (1860-1929), member of Louisiana House of Representatives from 1888 to 1904, Louisiana State Board of Education, and Tensas Parish School Board; Tensas school superintendent for some twenty years after 1904[49]

- Leon "Pee Wee" Whittaker, blues musician originally from Newellton

Politics

| Year | Republican | Democratic | Third parties |

|---|---|---|---|

| 2016 | 46.4% 1,182 | 52.3% 1,332 | 1.3% 34 |

| 2012 | 43.7% 1,230 | 55.6% 1,564 | 0.6% 18 |

| 2008 | 45.0% 1,367 | 54.1% 1,646 | 0.9% 27 |

| 2004 | 49.0% 1,453 | 49.6% 1,469 | 1.4% 41 |

| 2000 | 44.2% 1,330 | 52.5% 1,580 | 3.3% 100 |

| 1996 | 32.3% 1,000 | 60.7% 1,882 | 7.0% 217 |

| 1992 | 35.3% 1,153 | 51.0% 1,666 | 13.7% 447 |

| 1988 | 50.0% 1,645 | 47.3% 1,556 | 2.7% 89 |

| 1984 | 53.5% 1,956 | 44.5% 1,628 | 1.9% 71 |

| 1980 | 43.5% 1,645 | 54.1% 2,046 | 2.5% 94 |

| 1976 | 42.2% 1,553 | 56.6% 2,081 | 1.2% 43 |

| 1972 | 50.5% 1,729 | 45.8% 1,568 | 3.8% 129 |

| 1968 | 19.1% 503 | 32.0% 845 | 48.9% 1,290 |

| 1964 | 89.6% 1,655 | 10.4% 192 | |

| 1960 | 42.2% 510 | 20.5% 247 | 37.3% 451 |

| 1956 | 35.0% 359 | 31.6% 324 | 33.4% 343 |

| 1952 | 50.5% 703 | 49.5% 688 | |

| 1948 | 6.9% 72 | 22.9% 239 | 70.2% 734 |

| 1944 | 20.1% 160 | 80.0% 638 | |

| 1940 | 9.0% 95 | 91.0% 957 | |

| 1936 | 2.8% 23 | 97.3% 812 | |

| 1932 | 4.4% 29 | 95.5% 635 | 0.2% 1 |

| 1928 | 21.5% 96 | 78.5% 350 | |

| 1924 | 5.9% 21 | 94.2% 338 | |

| 1920 | 5.8% 15 | 94.2% 243 | |

| 1916 | 2.4% 5 | 96.7% 204 | 1.0% 2 |

| 1912 | 0.4% 1 | 91.7% 220 | 7.9% 19 |

References

- "State & County QuickFacts". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved August 18, 2013.

- "Find a County". National Association of Counties. Retrieved 2011-06-07.

- Swanton, John Reed (1952). The Indian Tribes of North America. US Government Printing Office. p. 210. ISBN 978-0-8063-1730-4.

- "Tensas Parish". Center for Cultural and Eco-Tourism. Retrieved September 5, 2014.

- "Indian Mounds of Northeast Louisiana: Flowery Mound". crt.state.la.us. Archived from the original on March 16, 2012. Retrieved October 22, 2011.

- Flowery Mound, Ancient Mounds Trail historical marker, St. Joseph, Louisiana

- Historical charts, NOAA

- John D. Winters, The Civil War in Louisiana, Baton Rouge: Louisiana State University Press, 1963, ISBN 0-8071-0834-0, p. 38

- Winters, p. 103

- Winters, p. 181

- Winters, pp. 392-393

- Franklin Plantation, historical marker, Newellton, Louisiana

- Clarence L. Mohr, "Bibliographical Essay: Southern Blacks in the Civil War: A Century of Historiography," Journal of Negro History, Vol. 59, No. 2 (1974).

- Winters, p. 398

- Lynching in America, Second Edition: Supplement by County, p. 4, Equal Justice Initiative, Mobile, AL, 2015

- Michael James Pfeifer, Rough Justice: Lynching and American Society, 1874-1947, University of Illinois Press, 2004, pp. 72-73

- James Matthew Reonas, Once Proud Princes: Planters and Plantation Culture in Louisiana's Northeast Delta, From the First World War Through the Great Depression, pp. Preface:6, and Appendix C: 283 (PDF). Baton Rouge: Louisiana State University Ph.D. dissertation, December 2006. Archived from the original (PDF) on September 21, 2013. Retrieved July 19, 2013.

- Jordan Flaherty. ""Did a Racist Coup in a Northern Louisiana Town Overthrow Its Black Mayor and Police Chief?", March 26, 2010". Dissident Voice. dissidentvoice.org. Retrieved June 12, 2010.

- Tensas Gazette, 12 May 2010

- Winters, pp. 6-7

- "Tensas Parish presidential election returns, November 8, 1988". staticresults.sos.la.gov. Retrieved November 11, 2012.

- "Tensas Parish presidential election returns, November 5, 1996". staticresults.sos.la.gov. Retrieved November 11, 2012.

- "Tensas Parish presidential election returns, November 7, 2000". staticresults.sos.la.gov. Retrieved November 11, 2012.

- "Tensas Parish presidential election returns, November 2, 2012". staticresults.sos.la.gov. Retrieved November 11, 2012.

- "Tensas Parish presidential election returns". staticresults.sos.la.gov. Retrieved November 11, 2012.

- "Tensas Parish presidential election returns, November 6, 2012". staticresults.sos.la.gov. Retrieved November 11, 2012.

- "Tensas Parish primary election returns, October 20, 2007". staticresults.sos.la.gov. Retrieved November 11, 2012.

- "2010 Census Gazetteer Files". United States Census Bureau. August 22, 2012. Archived from the original on September 28, 2013. Retrieved September 2, 2014.

- "Jane Merriett Netterville". voterportal.sos.la.gov. Archived from the original on October 10, 2013. Retrieved October 9, 2013.

- Advocate, The. "theadvocate.com - The Advocate - Baton Rouge News, Sports and Entertainment". The Advocate. Retrieved 16 April 2018.

- "Population and Housing Unit Estimates". Retrieved October 27, 2019.

- "U.S. Decennial Census". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved September 2, 2014.

- "Historical Census Browser". University of Virginia Library. Retrieved September 2, 2014.

- "Population of Counties by Decennial Census: 1900 to 1990". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved September 2, 2014.

- "Census 2000 PHC-T-4. Ranking Tables for Counties: 1990 and 2000" (PDF). United States Census Bureau. Retrieved September 2, 2014.

- John Marvin Bush, "The Tensas Gazette: A Brief Sketch," North Louisiana History, Vol. 5, No. 4 (Summer 1974), pp. 135-137

- Henry E. Chambers, History of Louisiana (Chicago: American Historical Society, 1925), pp. 206-207

- "Patricia Wilds Myers". files.usgwarchives.net. Retrieved June 8, 2013.

- "Tensas Gazette". mondotimes.com. Retrieved May 29, 2013.

- James Matthew Reonas, Once Proud Princes: Planters and Plantation Culture in Louisiana's Northeast Delta, From the First World War Through the Great Depression (PDF). Baton Rouge: Louisiana State University Ph.D. dissertation, December 2006, pp. 262-263. Archived from the original (PDF) on September 21, 2013. Retrieved July 19, 2013.

- Henry E. Chambers, History of Louisiana, Vol. 2 (Chicago and New York City: The American Historical Society, Inc., 1925, p. 71)

- "Membership of the Louisiana House of Representatives, 1812-2012: Tensas Parish" (PDF). legis.la.gov. Archived from the original (PDF) on October 4, 2013. Retrieved July 14, 2013.

- "Membership in the Louisiana State Senate, 1880-2012" (PDF). legis.state.la.us. Retrieved July 15, 2013.

- Obituary of Samuel Winter Martien, Tensas Gazette, June 7, 1946, p. 6

- "James E. Paxton". sixthda.com. Archived from the original on October 5, 2013. Retrieved October 4, 2013.

- Obituary of Clyde V. Ratcliff, Sr., Tensas Gazette, October 8, 1952

- Frederick W. Williamson and George T. Goodman, eds. Eastern Louisiana: A History of the Watershed of the Ouachita River and the Florida Parishes, 3 vols. (Monroe: Historical Record Association, 1939, pp. 569-571)

- "Garner H. Tullis", A Dictionary of Louisiana Biography, Vol. 2 (1988), p. 800

- Yearbook of American Clan Gregor Society, pp. 101-103. Richmond, Virginia: Appeals Press, 1916, Egbert Watson Magruder, ed. Retrieved July 18, 2013.

- Leip, David. "Dave Leip's Atlas of U.S. Presidential Elections". uselectionatlas.org. Retrieved 2018-03-07.

External links

- Tensas Progress Community Progress Site for Tensas

Gallery

- Tensas Parish welcoming sign on United States Highway 65

The Tensas Parish Civic Center is located at 115 Arts Drive off U.S. Highway 65 in St. Joseph.

The Tensas Parish Civic Center is located at 115 Arts Drive off U.S. Highway 65 in St. Joseph.- Former location downtown in St. Joseph of the weekly newspaper, The Tensas Gazette (established 1886).

- The Tensas Gazette currently shares space with the arts council at 118 Arts Drive.

- Flowers Landing Baptist Church, a Southern Baptist congregation at 2302 Louisiana Highway 888 northwest of Newellton, serves a rural clientele.

- Boating on popular Lake Bruin in Tensas Parish near St. Joseph

- Mississippi River levee road in Tensas Parish near St. Joseph

- The hay harvest south of Newellton (2016)