Hawfinch

The hawfinch (Coccothraustes coccothraustes) is a passerine bird in the finch family Fringillidae. Its closest living relatives are the evening grosbeak (Hesperiphona vespertinus) from North America and the hooded grosbeak (Hesperiphona abeillei) from Central America and Mexico.

| Hawfinch | |

|---|---|

| |

| Male in winter | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Aves |

| Order: | Passeriformes |

| Family: | Fringillidae |

| Subfamily: | Carduelinae |

| Genus: | Coccothraustes |

| Species: | C. coccothraustes |

| Binomial name | |

| Coccothraustes coccothraustes | |

| |

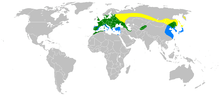

| Ranges of C coccothraustes Summer Resident Winter | |

| Synonyms | |

|

Loxia coccothraustes Linnaeus, 1758 | |

This bird breeds across Europe and temperate Asia (Palearctic). It is mainly resident in Europe, but many Asian birds migrate further south in the winter. It is a rare vagrant to the western islands of Alaska.

Deciduous or mixed woodland, including parkland, with large trees – especially hornbeam – is favoured for breeding. The hawfinch builds its nest in a bush or tree, and lays 2–7 eggs. The food is mainly seeds and fruit kernels, especially those of cherries, which it cracks with its powerful bill. This large finch species is usually seen in a pair or small group.

The 16.5–18 cm long hawfinch is a bulky bull-headed bird, which appears very short-tailed in flight. Its head is orange-brown with a black eyestripe and bib, and a massive bill, which is black in summer but paler in winter. The upper parts are dark brown and the underparts orange.

The white wing bars and tail tip are striking in flight. The sexes are similar. The call is a hard chick. The song of this unobtrusive bird is quiet and mumbled.

Taxonomy

The hawfinch was described and illustrated by Swiss naturalist Conrad Gesner in his Historiae animalium in 1555.[2] He used the Latin name Coccothraustes which is derived from the Greek: kokkos is a seed or kernel and thrauō means to break or to shatter.[3] In 1758 Carl Linnaeus included the species in the 10th edition of his Systema Naturae under the binomial name Loxia coccothraustes.[4][5] The hawfinch was moved to a separate genus Coccothraustes by the French zoologist Mathurin Jacques Brisson in 1760.[4][6] The English name 'hawfinch' was used by the ornithologist Francis Willughby in 1676.[7][8] Haws are the red berries of the common hawthorn (Crataegus monogyna).

Molecular phylogenetic studies have shown that the hawfinch is closely related to other grosbeaks in the Eophona, Hesperiphona and Mycerobas genera. Finches with large beaks in the Rhynchostruthus and Rhodospiza genera are not closely related. The similar bill morphology is the result of convergence due to the similar feeding behaviour.[9]

Fossil record:

- Coccothraustes balcanicus (Late Pliocene/Late Villafranchian of Slivnitsa, western Bulgaria)[10]

- Coccothraustes simeonovi (Late Pliocene/Middle Villafranchian of Varshets, western Bulgaria)[10]

There are six recognised subspecies:[11]

- western hawfinch (C. c. coccothraustes) (Linnaeus, 1758) – Europe to central Siberia and northern Mongolia

- Northwest African hawfinch (C. c. buvryi) Cabanis, 1862 – northwestern Africa

- Caucasian hawfinch (C. c. nigricans) Buturlin, 1908 – southern Ukraine, the Caucasus, northeastern Turkey and northern Iran

- C. c. humii Sharpe, 1886 – southern Kazakhstan, eastern Uzbekistan and northeastern Afghanistan

- C. c. schulpini Johansen, H, 1944 – southeastern Siberia, northeastern China and Korea

- Japanese hawfinch (C. c. japonicus) Temminck & Schlegel, 1848 – the Kamchatka Peninsula, Sakhalin, the Kuril Islands and Japan

Description

The hawfinch has an overall length of 18 cm (7.1 in), with a wingspan that ranges from 29 to 33 cm (11 to 13 in). It weighs 46–70 g (1.6–2.5 oz) with the male being on average slightly heavier than the female.[12] It is a robust bird with a thick neck, large round head and a wide, strong conical beak with a metallic appearance. It has short pinkish legs with a light hue and it has a short tail. It has brown eyes. The plumage of the female is slightly paler than that of the male. The overall colour is light brown, its head having an orange hue to it. Its eyes have a black circle around them, extending to its beak and surrounding it at its edge. Its throat is also black. The sides of its neck, as well as the back of its neck, are gray. The upper side of its wings are a deep black colour. The wings also have three stripes from approximately the middle till their sides: a white, a brown and a blue stripe. Adults moults between July and September.

Distribution and habitat

The hawfinch is distributed in the whole of Europe, Eastern Asia (Palearctic including North Japan), and North Africa (Morocco, Tunisia and Algeria). It has also been sighted in Alaska, but this is reported as an accidental presence. It is not found in Iceland, parts of the British Isles, Scandinavia or certain Mediterranean islands. It is however found in southern Europe, such as in Spain and Bulgaria, as well as in central Europe, including parts of England and southern Sweden. In Asia it can be found in the Caucasus, northern Iran, Afghanistan, Turkistan, Siberia, Manchuria and North Korea.

The hawfinch typically inhabits deciduous forests during the spring to have offspring, often in trees that bear fruit, such as oak trees. They also incur into human areas, such as parks and gardens. They can also be found in pine woods, as long as there is a source of water in the vicinity. During autumn and winter they seek food-providing forests, especially those with cherry and plum trees. As for height, the hawfinch is present in any altitude up to that which is limited by the size of the trees.

The British Isles

In the 18th century, the hawfinch was recorded as only a rare winter visitor in Britain. The first breeding record was early in the 19th century; by the early 1830s, a well-documented colony was established at Epping Forest in Essex, and breeding was also recorded in other counties east and south of London. Further expansion of the range continued through the 19th and 20th centuries, with breeding occurring as far north as Aberdeenshire by 1968–1972. Peak numbers were in the period 1983–1990. Subsequently, there has been a significant decline of between 37% and 45% between 1990–1999.[13][14][15][16]

Southeastern England is the stronghold of the hawfinch in Britain. One well-known site is Bedgebury Pinetum, where flocks gather to roost in winter. The species is also found in the New Forest; a central roost site exists here, at the Blackwater Arboretum. The only Sussex stronghold is at Westdean Woods in West Sussex, while in Surrey they are regularly seen at Bookham Common in winter. Formerly, hawfinches were regularly encountered in the Windsor Great Park area in winter, though no sizeable gatherings have been reported since the mid-1990s. The recent (2007–11) BTO Bird Atlas shows no evidence of the hawfinch breeding anywhere in this area; the reasons why are unclear.

In Devon (southwestern England), the hawfinch is largely confined to the upper Teign Valley. In western England and Wales, two areas in which hawfinches reliably occur are the Forest of Dean and the Wyre Forest. In Eastern England, the hawfinch is present in the Breckland of East Anglia. In northern England, hawfinches are regularly found in a small number of locations. Prime sites include Fountains Abbey in Yorkshire and Hulne Park in Northumberland. Hawfinches can be seen at Cromford Derbyshire near the canal and at Clumber Park (Nottinghamshire) near the chapel. In Scotland, Scone Palace near Perth is the most well-known site in Scotland for hawfinches. Formerly, they also occurred in the Royal Botanic Garden Edinburgh. In Ireland, they are an annual winter visitor in small numbers: they are most often seen at Curraghchase Forest Park in County Limerick, where a flock of between 15 and 30 birds occurs each winter.

Behaviour and ecology

The hawfinch is a shy species, and therefore difficult to observe and study. It spends most of the day on top of high branches, above all during breeding season. During the course of the hawfinch's life it can only be seen on the ground while looking for seeds or drinking water, always near trees. While drinking and eating it is fairly aggressive and dominant, towards both its same species or different ones, even bigger birds. It guards a quite small territory when its chicks are born; however, when not bearing any offspring it is known to guard entire woods. This is interpreted as an evolutionary advantage, given colony rearing is seen as safer against nest predators.

Breeding

Hawfinches first breed when they are 1 year old.[17] They are monogamous, with a pair-bond that sometimes persists from one year to the next. Pair-formation takes place before the breakup of the wintering flocks.[18] The date for breeding is dependent on the spring temperature and is earlier in southwest Europe and later in the northeast. In Britain, most clutches are laid between late April and late June.[12]

Hawfinches engage in an elaborate series of courtship routines. The two birds stand apart facing one another and reach out to touch their bills. The male displays to the female by standing erect, puffing out the feathers on his head, neck and chest and allowing his wings to droop forward. He then makes a deep bow. The male will also lower a wing and move it in a semi-circular arc, revealing his wing bars and modified wing feathers.[19]

The breeding pairs are usually solitary, but they occasionally breed in loose groups.[18] The nest is normally located high in a tree on a horizontal branch with easy access from the air.[17] The male chooses the site of the nest and builds a layer of dry twigs. After a few days, the female takes over.[20] The nest is untidy and is formed of a bulky twig base and a shallow cup lined with roots, grasses and lichens.[21] The eggs are laid in early morning at daily intervals.[17] The clutch is normally 4–5 eggs.[21] There is considerable variable in the colour and shape of the eggs.[17] They have purple brown and pale grey squiggles on a background that can be buff, grey-green or pale blueish.[21] The average size is 24.1 mm × 17.5 mm (0.95 in × 0.69 in) with a calculated weight of 3.89 g (0.137 oz).[17] The eggs are incubated for 11–13 days by the female.[17] The nestlings are fed by both parents, who regurgitate seeds but also bring mouthfuls of caterpillars.[22] Initially, the male normally passes the food to the female who feeds the chicks, but as they grow bigger both adults feed them directly.[17] The female broods the chicks while they are in the nest.[17] They fledge after 12–14 days and the young birds become independent of their parents around 30 days later.[21] The parents generally only raise a single brood each year.[17]

The hawfinch is highly unusual among cardueline finches in that the male bird chooses the nest site and starts the construction. In other species the female performs these roles.[23] The hawfinch is also unusual in that the nest is kept clean by the parents removing the faecal sacs of the nestlings right up to the time when the chicks fledge. This behaviour is shared by the Eurasian bullfinch, but most finches cease to remove the faecal material after the first few days.[24]

The annual survival rate is not known.[25] The maximum age obtained from ring-recovery data is 12 years and 7 months for a bird in Germany.[26]

Feeding

The hawfinch feeds primarily on hard seeds from trees, as well as fruit seeds, which it obtains with the help of its strong beak with accompanying jaw muscles. Its jaw muscles exert a force equivalent to a load of approximately 30–48 kg. Thus it can break through the seeds of cherries and plums. Other common sources of food include pine seeds, berries, sprouts and the occasional caterpillar and beetle. They can also break through olive seeds. The bird is known to eat in groups, especially during the winter.

Flight

Its flight is quick and its trajectory is straight over short distances. During long flights periodical undulations can be observed in their flight pattern. While on the ground scavenging it hops, and they are quick to fly away at the slightest noise. They are observed to catch insects mid-flight. They fly up to a height of 200 m and they are seen to fly in groups, as well as alone.

Migration

The hawfinch is a partial migrant, with northern flocks migrating towards the South during the winter, as shown by ringing techniques. These same studies showed that those hawfinches inhabiting habitats with a temperate climate would often have sedentary behaviour. A few migrants from northern Europe reach Britain in autumn and some are seen on the Northern Isles in spring.

Status

The European population of the hawfinch is estimated to be between 7,200,000 and 12,600,000 individuals. Assuming that the European range is between 25 percent and 49 percent of the global range, a tentative figure for the global population size is 14,700,000–50,400,000 individuals. States with large populations include Romania (500,000–1,000,000 pairs), Croatia (250,000–500,000 pairs) and Germany (200,000–365,000 pairs). Although the global population appears to be stable,[1] the population within the United Kingdom underwent a 76 percent reduction between 1968 and 2011. In 2013 it was estimated that there were only 500–1000 breeding pairs. The reasons for this decline are not understood.[27] Given the high numbers and huge breeding area, the hawfinch is classified by the International Union for Conservation of Nature as being of least concern.[1]

References

- BirdLife International (2012). "Coccothraustes coccothraustes". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. 2012. Retrieved 26 November 2013.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Gesner, Conrad (1555). Historiæ animalium liber III qui est de auium natura. Adiecti sunt ab initio indices alphabetici decem super nominibus auium in totidem linguis diuersis: & ante illos enumeratio auium eo ordiné quo in hoc volumine continentur (in Latin). Zurich: Froschauer. pp. 264–265.

- Jobling, James A (2010). The Helm Dictionary of Scientific Bird Names. London: Christopher Helm. p. 212. ISBN 978-1-4081-2501-4.

- Paynter, Raymond A. Jnr., ed. (1968). Check-list of Birds of the World. Volume 14. Cambridge, Massachusetts: Museum of Comparative Zoology. pp. 299–300.

- Linnaeus, C. (1758). Systema Naturæ per regna tria naturae, secundum classes, ordines, genera, species, cum characteribus, differentiis, synonymis, locis (in Latin). Volume 1 (10th ed.). Holmiae:Laurentii Salvii. p. 171.

- Brisson, Mathurin Jacques (1760). Ornithologie (in French). Paris: Chez C.J.-B. Bauche. Vol. 1, p. 36, Vol. 3 p. 218.

- Willughby, Francis (1676). Ornithologiae Libri Tres (in Latin). London: John Martyn. p. 178.

- Willughby, Francis (1778). The Ornithology of Francis Willughby of Middleton in the County of Warwick. London: John Martyn. p. 244.

- Zuccon, Dario; Prŷs-Jones, Robert; Rasmussen, Pamela C.; Ericson, Per G.P. (2012). "The phylogenetic relationships and generic limits of finches (Fringillidae)" (PDF). Molecular Phylogenetics and Evolution. 62 (2): 581–596. doi:10.1016/j.ympev.2011.10.002. PMID 22023825.

- Boev, Z. 1998. Late Pliocene Hawfinches (Coccothraustes Brisson, 1760) (Aves: Fringillidae) from Bulgaria. – Historia naturalis bulgarica, 9: 87–99.

- Gill, Frank; Donsker, David (eds.). "Finches, euphonias". World Bird List Version 5.2. International Ornithologists' Union. Retrieved 5 June 2015.

- Snow & Perrins 1998, pp. 1610–1613.

- Holloway, S. (1996). The Historical Atlas of Breeding Birds in Britain and Ireland: 1875–1900. T & A D Poyser ISBN 0-85661-094-1.

- Sharrock, J. T. R. (1976). The Atlas of Breeding Birds in Britain and Ireland. British Trust for Ornithology / Irish Wildbird Conservancy ISBN 0-903793-01-6.

- Gibbons, D. W., Reid, J. B., & Chapman, R. A., eds. (1993). The New Atlas of Breeding Birds in Britain and Ireland: 1988–1991. T & A D Poyser ISBN 0-85661-075-5.

- Langston, R.H.W.; Gregory, R.D.; Adams, R. (2002). "The status of the Hawfinch in the UK 1975–1999" (PDF). British Birds. 95: 166–173.

- Cramp & Perrins 1994, pp. 843–844.

- Clement, P. "Hawfinch (Coccothraustes coccothraustes)". In del Hoyo, J; Elliott, A.; Sargatal, J.; Christie, D.A.; de Juana, E. (eds.). Handbook of the Birds of the World Alive. Lynx Edicions. Retrieved 6 June 2015.(subscription required)

- Newton 1972, pp. 167–168.

- Newton 1972, pp. 166–167.

- Newton 1972, p. 63.

- Newton 1972, p. 167.

- Collar, N.; Newton, I.; Bonan, A. (2013). "Finches (Fringillidae)". In del Hoyo, J; Elliott, A.; Sargatal, J.; Christie, D.A.; de Juana, E. (eds.). Handbook of the Birds of the World Alive. Lynx Edicions. Retrieved 31 August 2015.(subscription required)

- Newton 1972, pp. 166,169.

- Robinson, R.A. (2005). "BirdFacts: profiles of birds occurring in Britain & Ireland (BTO Research Report 407): Hawfinch Coccothraustes coccothraustes [Linnaeus, 1758]". British Trust for Ornithology. Retrieved 18 June 2015.

- Fransson, T.; Kolehmainen, T.; Kroon, C.; Jansson, L.; Wenninger, T. (2010). "EURING list of longevity records for European birds". European Union for Bird Ringing. Retrieved 18 June 2015.

- Kirby, Will B.; Bellamy, Paul E.; Stanbury, Andrew J.; Bladon, Andrew J.; Grice, Phil V.; Gillings, Simon (2015). "Breeding season habitat associations and population declines of British Hawfinches Coccothraustes coccothraustes". Bird Study. 62 (3): 348–357. doi:10.1080/00063657.2015.1046368.

Sources

- Cramp, Stanley; Perrins, C.M., eds. (1994). Handbook of Birds of Europe the Middle East and North Africa: Birds of the Western Palearctic. Volume 8: Crows to Finches. Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-854679-3.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Newton, Ian (1972). Finches. The New Naturalist, Volume 55. London: Collins. ISBN 0-00-213065-3.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Snow, D.W.; Perrins, C.M., eds. (1998). The Birds of the Western Palearctic, Concise Edition, Volume 2: Passerines. Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-850188-9.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

Further reading

- Mountfort, Guy (1957). The Hawfinch. London: Collins. OCLC 559650.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Coccothraustes coccothraustes. |

- Oiseaux Photos

- Ageing and sexing (PDF; 4.1 MB) by Javier Blasco-Zumeta & Gerd-Michael Heinze

- Audio recordings from Xeno-canto

- Videos and photos from the Internet Bird Collection

]