Apocalypse Tapestry

The Apocalypse Tapestry is a large medieval French set of tapestries commissioned by Louis I, the Duke of Anjou, and produced between 1377 and 1382. It depicts the story of the Apocalypse from the Book of Revelation by Saint John the Divine in colourful images, spread over a number of sections that originally totalled 90 scenes. Despite being lost and mistreated in the late 18th century, the tapestry was recovered and restored in the 19th century and is now on display at the Chateau d'Angers. It is the oldest French medieval tapestry to have survived, and historian Jean Mesqui considers it "one of the great artistic interpretations of the revelation of Saint John, and one of the masterpieces of French cultural heritage".[1]

| The Apocalypse Tapestry | |

|---|---|

| |

| Artist | Jean Bondol and Nicholas Bataille |

| Year | 1377–1382 |

| Type | Tapestry |

| Location | Musée de la Tapisserie, Château d'Angers, Angers |

History

The Apocalypse Tapestry was commissioned by Louis I, the Duke of Anjou in the late 1370s.[2] Louis instructed Jean Bondol, a Flemish artist, to draw the sketches that would form the model for the tapestry, which was then woven in Paris between 1377 and 1380 by Nicholas Bataille.[3] The tapestry was probably finally complete by 1382.[2] It was unusual for a tapestry to be commissioned by a buyer to a specific design in this way.[4] It is uncertain how Louis used the tapestry; it was probably intended to be displayed outside, supported by six wooden structures, possibly arranged so as to position the viewer near to the centre of the display, imitating a jousting field.[5] The tapestry and its theme would have also helped to bolster the status of Louis's Valois dynasty, then involved in the Hundred Years' War with England.[5]

The tapestry shows the story of the Apocalypse from the Book of Revelation by Saint John the Divine.[6] In the 14th century, the Apocalypse was a popular story, focusing on the heroic aspects of the last confrontation between good and evil and featuring battle scenes between angels and beasts.[7] Although many of the scenes in the story included destruction and death, the account ended with the triumphant success of good, forming an uplifting story.[8] Various versions of the Apocalypse story, or cycle, were circulating in Europe at the time and Louis chose to use an Anglo-French Gothic style of the cycle, partially derived from a manuscript he borrowed from his brother, Charles V of France, in 1373.[2] This version of the Apocalypse had first been recorded in Metz and then later adapted by English artists; Charles' manuscript had been produced in England around 1250.[9] Louis may also have been influenced by a particularly grand tapestry given to Charles by the magistrates of Lille in 1367.[10]

After a century in the ownership of the dukes of Anjou, René of Anjou bequeathed the tapestry to Angers Cathedral in 1480 where it remained for many years.[1] During the French Revolution the Apocalypse Tapestry was looted and cut up into pieces. The pieces of the tapestry were used for various purposes: as floor mats, to protect local orange trees from frost, to shore up holes in buildings, and to insulate horse stables.[11] During the Revolution many medieval tapestries were destroyed, both through neglect and through being melted down to recover the gold and silver used in their designs.[12] The surviving fragments were rediscovered in 1848 and preserved, being returned to the cathedral in 1870.[13]

The cathedral was not ideal for displaying and preserving the tapestry.[14] The neighbouring Chateau d'Angers had been used as a French military base for many years, but transferred to civilian use after the Second World War. In 1954 the tapestry was moved there, to be displayed in a new gallery designed by French architect Bernard Vitry.[13] Between 1990 and 2000 the castle gallery was itself improved, with additional light and ventilation controls installed to protect the tapestry.[14]

Description and style

The tapestry was made in six sections, each 78-foot (24 m) wide by 20-foot (6.1 m) high, comprising 90 different scenes.[15] Each scene had a red or blue background, alternating between the sections.[16] They would have taken considerable effort to produce, with between 50 and 84 man-years of effort required by the weaving teams.[17] Only 71 of the original 90 scenes survive today.[18] The tapestry is dominated by blue, red and ivory coloured threads, supported by orange and green colours, with gilt and silver woven into the wool and silk.[19] These colours are now considerably faded on the front of the tapestry but were originally similar to the deep and vibrant hues seen on the back of the tapestry panels.[20]

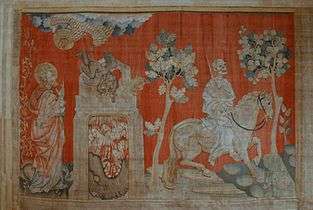

Jean Bondol's weaving follows the Franco-Flemish school of tapestry design, with rich, realist, fluid images placed into a simple, clear structure through the course of the tapestry.[21] As a result, the angels and monsters are depicted with considerable energy and colour, the impact reinforced by the sheer size of the tapestry, which allows them to be portrayed slightly larger than life-size.[22] Various approaches are taken in the tapestry to interpreting the allegorical language used by St John in his original text; in particular, the tapestry takes an unusual approach to portraying the Fourth Horseman of the Apocalypse, Death. The depiction of Death in this tapestry follows the style then becoming popular in England: he is represented as a decaying corpse, rather than the more common 14th century portrayal of Death as a conventional, living person.[23]

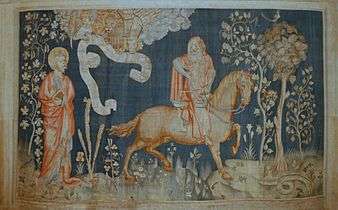

- The first horseman: Conquest

The third horseman: Famine

The third horseman: Famine The fourth horseman: Death - represented as a decaying corpse

The fourth horseman: Death - represented as a decaying corpse The eagle of Doom

The eagle of Doom

References

- Mesqui, p.49.

- Mesqui, p.44.

- Mesqui, p.44; Klein, p.191.

- Bell, p.64.

- Mesqui, p.50.

- Bausum, p.70.

- Aberth, p.186; Benton, p.199.

- Mesqui, p.45.

- Klein, pp.188-189, 191; Aberth, p.190.

- Bell, p.88.

- Benton, p.200; Belozerskaya, p.92.

- Belozerskaya, p.92.

- Mesqui, p.39.

- Mesqui, p.40.

- Bausum, p.70.

- Benton, p.199.

- Bell, p.66.

- Benton, p.200.

- Bausum, p.70; Mesqui, p.48; Bell, p.66.

- Bausum, p.70; Mesqui, p.48.

- Mesqui, p.48.

- Benton, p.200; Bausum, p.70.

- Aberth, pp.187, 190.

Bibliography

- Aberth, John (2001). From the Brink of the Apocalypse: Confronting Famine, War, Plague and Death in the Later Middle Ages. London: Routledge. ISBN 9780415927154.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Bausum, Dolores (2001). Threading Time: A Cultural History of Threadwork. Fort Worth, US: TCU Press. ISBN 9780415927154.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Bell, Susan Groag (2004). The Lost Tapestries of the City of Ladies: Christine de Pizan's Renaissance Legacy. Berkeley, US: University of California Press. ISBN 9780520234109.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Belozerskaya, Marina (2004). Luxury Arts of the Renaissance. Los Angeles, US: J. Paul Getty Museum. ISBN 9780892367856.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Benton, Janetta Rebold (2009). Materials, Methods and Masterpieces of Medieval Art. Santa Barbara, US: Praeger. ISBN 9780275994181.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Klein, Peter K. (1992). "Introduction: The Apocalypse in Medieval Art". In Emmerson, Richard K.; McGinn, Bernard (eds.). The Apocalypse in the Middle Ages. New York, US: Cornell University Press. ISBN 9780801495502.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Mesqui, Jean (2001). Château d'Angers. Paris: Centre des monuments nationaux. ISBN 9782858226047.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Apocalypse Tapestry. |