Tapejaridae

Tapejaridae (from a Tupi word meaning "the old being") are a family of pterodactyloid pterosaurs from the Cretaceous period. Members are currently known from Brazil, England, Hungary, Morocco,[2] Spain[3] and China, where the most primitive genera are found, indicating that the family has an Asian origin.[4]

| Tapejarids | |

|---|---|

| |

| Reconstructed skeleton of Tapejara wellnhoferi | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Order: | †Pterosauria |

| Suborder: | †Pterodactyloidea |

| Clade: | †Tapejaromorpha |

| Family: | †Tapejaridae Kellner, 1989 |

| Type species | |

| †Tapejara wellnhoferi Kellner, 1989 | |

| Genera | |

| |

Description

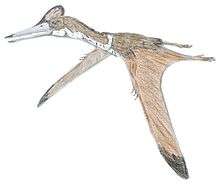

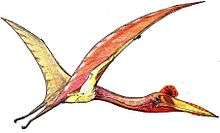

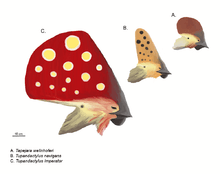

Tapejarids were small to medium-sized pterosaurs with several unique, shared characteristics, mainly relating to the skull. Most tapejarids possessed a bony crest arising from the snout (formed mostly by the premaxillary bones of the upper jaw tip). In some species, this bony crest is known to have supported an even larger crest of softer, fibrous tissue that extends back along the skull. Tapejarids are also characterized by their large nasoantorbital fenestra, the main opening in the skull in front of the eyes, which spans at least half the length of the entire skull in this family. Their eye sockets were small and pear-shaped.[5] Studies of tapejarid brain cases show that they had extremely good vision, more so than in other pterosaur groups, and probably relied nearly exclusively on vision when hunting or interacting with other members of their species.[6] Tapejarids had unusually reduced shoulder girdles that would have been slung low on the torso, resulting in wings that protruded from near the belly rather than near the back, a "bottom decker" arrangement reminiscent of some planes.[6]

Biology

Tapejarids appear to have been arboreal, having more curved claws than other azhdarchoid pterosaurs and occurring more commonly in fossil sites with other arboreal flying vertebrates such as early birds. Tapejarids have long been speculated as having been frugivores or omnivores, based on their parrot-like beaks.[7] Direct evidence for plant-eating is known in a specimen of Sinopterus that preserves seeds in the abdominal cavity. The Barremian- Aptian distribution of some tapejarids may even be partially associated with the first radiation phase of the angiosperms, especially of the genus Klitzschophyllites which represents a more basal angiosperm.[8] [9]

Classification

Tapejaridae was defined by Alexander Kellner in 1989 as the clade containing both Tapejara and Tupuxuara, plus all descendants of their most recent common ancestor. As originally conceived, it was composed of two subfamilies: the Tapejarinae of "Huaxiapterus" corollatus, Sinopterus, Tapejara, Tupandactylus, Europejara, Caiuajara, and possibly Bakonydraco, and the Thalassodrominae of Thalassodromeus and Tupuxuara.[10]

Some studies, such as one by Lü and colleagues in 2008, have found that the thalassodromines are more closely related to the azhdarchids proper than to the tapejarids,[11] and have placed them in their own family (which has sometimes been referred to as Tupuxuaridae,[12] though Thalassodrominae was named first[10]). At least one study has also found that the Chaoyangopteridae, often found to be closer to azhdarchids, represent a lineage within the Tapejaridae, more closely related to the tapejarines than to the thalassodromines. Felipe Pinheiro and colleagues (2011) reclassified the group as a subfamily of Tapejaridae, Chaoyangopterinae, for this reason.[5]

The exact relationships of tapejarids to one another and to other azhdarchoid pterosaurs has historically been unclear, with different studies producing significantly different cladograms (family trees). It is also unclear exactly which pterosaurs belong to the Tapejaridae; some researchers have found the thalassodromines and chaoyangopterines to be members of this family,[5][10] while other studies have found them to be more closely related to the azhdarchids (in the clade Neoazhdarchia).[13] Several studies have shown that the "tapejarids" as traditionally thought of (that is, including the classic examples of both Tapejara and Tupuxuara) are paraphyletic, and do not form a natural group, but instead represent sequential branches of the tree leading. In light of this discovery, several of the traditional names associated with the group have been re-defined. Martill and Naish proposed a revised definition for Tapejaridae, as all species more closely related to Tapejara than to Quetzalcoatlus.[13] Andres and colleagues did not follow this proposal, instead formally defining Tapejaridae as the clade Tapejara + Sinopterus. They also re-defined the Tapejarinae as all species closer to Tapejara than to Sinopterus, and added a new clade, Tapejarini, to include all descendants of the last common ancestor of Tapejara and Tupandactylus.[14]

Below are two alternate cladograms: the first, presented by Andres, Clark and Xu (2014), found the a grouping of tapejarids at the base of the clade, with thalassodromids more closely related to azhdarchids and chaoyangopterids, as well as dsungaripterids.[14] The second, presented by Vidovic and Martill (2014), found tapejarines and chaoyangopterines to be the closest relatives of azhdarchids, followed by thalassodromids (represented by Tupuxuara).[15]

| Azhdarchoidea |

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Dsungaripteroidea |

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

References

- David M. Martill; Mick Green; Roy Smith; Megan Jacobs; John Winch (2020). "First tapejarid pterosaur from the Wessex Formation (Wealden Group: Lower Cretaceous, Barremian) of the United Kingdom". Cretaceous Research. in press: Article 104487. doi:10.1016/j.cretres.2020.104487.

- Peter Wellnhofer, Eric Buffetaut (1999). "Pterosaur remains from the Cretaceous of Morocco". Paläontologische Zeitschrift. 73 (1–2): 133–142. doi:10.1007/BF02987987.

- Vullo, R.; Marugán-Lobón, J. S.; Kellner, A. W. A.; Buscalioni, A. D.; Gomez, B.; De La Fuente, M.; Moratalla, J. J. (2012). Claessens, Leon (ed.). "A New Crested Pterosaur from the Early Cretaceous of Spain: The First European Tapejarid (Pterodactyloidea: Azhdarchoidea)". PLoS ONE. 7 (7): e38900. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0038900. PMC 3389002. PMID 22802931.

- Lü, J.; Jin, X.; Unwin, D.M.; Zhao, L.; Azuma, Y.; Ji, Q. (2006). "A new species of Huaxiapterus (Pterosauria: Pterodactyloidea) from the Lower Cretaceous of western Liaoning, China with comments on the systematics of tapejarid pterosaurs". Acta Geologica Sinica. 80 (3): 315–326. doi:10.1111/j.1755-6724.2006.tb00251.x.

- Pinheiro, F.L.; Fortier, D.C.; Schultz, C.L.; De Andrade, J.A.F.G.; Bantim, R.A.M. (2011). "New information on Tupandactylus imperator, with comments on the relationships of Tapejaridae (Pterosauria)". Acta Palaeontologica Polonica. 56: 567–580. doi:10.4202/app.2010.0057.

- Eck, K.; Elgin, R.A.; Frey, E. (2011). "On the osteology of Tapejara wellnhoferi KELLNER 1989 and the first occurrence of a multiple specimen assemblage from the Santana Formation, Araripe Basin, NE-Brazil". Swiss Journal of Palaeontology. 130 (2): 277–296. doi:10.1007/s13358-011-0024-5.

- Wu, Wen-Hao; Zhou, Chang-Fu; Andres, Brian (2017). "The toothless pterosaur Jidapterus edentus (Pterodactyloidea: Azhdarchoidea) from the Early Cretaceous Jehol Biota and its paleoecological implications". PLoS ONE. 12 (9): e0185486. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0185486. PMC 5614613. PMID 28950013.

- Meng, X. (2008). "A New Species of Sinopterus from Jehol Biota and Reconstraction of Stratigraphic Sequence of the Jiufotang Formation". Thesis, Chinese Academy of Sciences.

- Could Tapejarid Pterosaurs be the dispersers of Klitzschophyllites angiosperm? A preliminary case of study of zoocory Flaviana J. Lima 1*, Renan A. M. Bantim1,2, Antônio A. F. Saraiva1 & Juliana M. Sayão3

- Kellner, A.W.A.; Campos, D.A. (2007). "Short note on the ingroup relationships of the Tapejaridae (Pterosauria, Pterodactyloidea". Boletim do Museu Nacional. 75: 1–14.

- Lü, J., Unwin, D.M., Xu, L., and Zhang, X. (2008). "A new azhdarchoid pterosaur from the Lower Cretaceous of China and its implications for pterosaur phylogeny and evolution." Naturwissenschaften,

- Martill, D.M., Bechly, G., and Heads, S.W. (2007). "Appendix: species list for the Crato Formation." In: Martill, D.M., Bechly, G., and Loveridge, R.F. (eds.), 2007. The Crato Fossil Beds of Brazil: Window into an Ancient World. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge. Pp. 582–607.

- Martill, D.M.; Naish, D. (2006). "Cranial crest development in the azhdarchoid pterosaur Tupuxuara, with a review of the genus and tapejarid monophyly". Palaeontology. 49 (4): 925–941. doi:10.1111/j.1475-4983.2006.00575.x.

- Andres, B.; Clark, J.; Xu, X. (2014). "The Earliest Pterodactyloid and the Origin of the Group". Current Biology. 24 (9): 1011–6. doi:10.1016/j.cub.2014.03.030. PMID 24768054.

- Vidovic, S. U.; Martill, D. M. (2014). "Pterodactylus scolopaciceps Meyer, 1860 (Pterosauria, Pterodactyloidea) from the Upper Jurassic of Bavaria, Germany: The Problem of Cryptic Pterosaur Taxa in Early Ontogeny". PLoS ONE. 9 (10): e110646. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0110646. PMC 4206445. PMID 25337830.