Douzhanopterus

Douzhanopterus is an extinct genus of monofenestratan pterosaur from the Late Jurassic of Liaoning, China. It contains a single species, D. zhengi, named by Wang et al. in 2017. In many respects, it represents a transitional form between basal pterosaurs and the more specialized pterodactyloids; for instance, its tail is intermediate in length, still being about twice the length of the femur but relatively shorter compared to that of the more basal Wukongopteridae. Other intermediate traits include the relative lengths of the neck vertebrae and the retention of two, albeit reduced, phalanx bones in the fifth digit of the foot. Phylogenetically, Douzhanopterus is nested between the wukongopterids and a juvenile pterosaur specimen from Germany known as the "Painten pro-pterodactyloid", which is similar to Douzhanopterus in many respects but approaches pterodactyloids more closely elsewhere.

| Douzhanopterus | |

|---|---|

| |

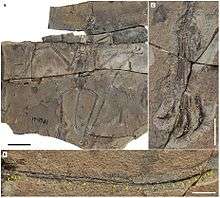

| Photograph of the type specimen of Douzhanopterus (a) with closeups of the tail (b) and foot (c) | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Order: | †Pterosauria |

| Clade: | †Pterodactyliformes |

| Genus: | †Douzhanopterus Wang et al., 2017 |

| Type species | |

| †Douzhanopterus zhengi Wang et al., 2017 | |

Description

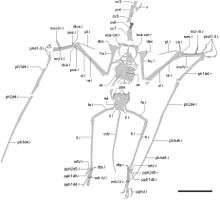

Douzhanopterus was a relatively small pterosaur, with a wingspan of only 74 centimetres (29 in). The only known specimen represents an adult, judging by the degree of fusion in the hand bones, scapulocoracoid, and the tibia-fibula, as well as the fusion of the extensor tendon on the wing to the first phalanx of the wing.[1][2][3]

Out of nine cervical vertebrae,[4] the last seven are definitely preserved, and the atlas and axis may also be present. These vertebrae are long, generally about 2.5 to 3.5 times as long as they are wide. The vertebrae bear distinct condyles for articulation with other vertebrae, and the neural spines are directed backwards and upwards; the ones near the middle also have prominent zygapophyses. Further along the vertebral column, there would have been 13 dorsal vertebrae in total, followed by six sacral vertebrae that form a sacrum. These two types of vertebrae are similar, although the sideways-projecting transverse processes are more robust in the latter. In the tail were 22 caudal vertebrae, totalling to 83.86 mm (3.302 in) long, which is 173% the length of the humerus. They increase in length from the first to the sixth but then become smaller after this point. Up until about the sixteenth caudal vertebra, the zygapophyses and chevrons are very long.[1]

Overall, the sternum is about as long as it is wide, with a forward-projecting front margin but a straight back margin. The scapula is slender and long, being about 40% longer than the coracoid; the coracoid itself does not bear any sort of expansion on its bottom surface. On the humerus, the deltopectoral crest is short and trapezoidal, and is placed at the top of the bone. A small crest is also present where the humerus articulates with the ulna. The pteroid, a bone unique to pterosaurs, is quite long, being about half as long as the ulna. In front of the pteroid, there is a small sesamoid bone that is attached to the outer edge of the carpals. The digits of the non-wing hand are somewhat long, being about 65% of humerus length and 53% of ulna length, and bear large claws. On the wing finger, the second phalanx is the longest, followed by the first and third, and then the fourth, which is still about 80% the length of the second.[1]

Fused entirely to the sacrum is the pelvic girdle. The portion of the pelvic girdle in front of the femoral joint appears to consist of two unfused prepubes, which are longer than they are wide. The femur is slightly curved, and the femoral head and neck form an angle of about 150° with the shaft. On the lower leg, the relatively straight tibia is about 180% the length of the femur; the fibula, which is about 45% the length of the tibia, is fused to it at both ends. Further below, the five metatarsals are rectangular. The second metatarsal is also the longest, followed again by the first and third, and then the fourth, with the third metatarsal being about 31% the length of the tibia. Unusually, the fifth digit of the foot still has two phalanges, the first straight and the second curved; the first is about 20% the length of the third metatarsal.[1]

Discovery and naming

The holotype specimen of Douzhanopterus, a skeleton lacking the skull, is preserved on a plate and counterplate. The plate and counterplate are respectively catalogued as STM 19–35A and STM 19–35B, and they are stored at the Shandong Tianyu Museum of Nature in Shandong, China. This specimen was purchased from a local farmer, who claimed that it had been excavated at Toudaoyingzi, Jiangchang in Liaoning province. However, the rock encasing the specimen is characteristic of sediments found at another locality within Liaoning, Linglongta. The latter belongs to the fossil-rich units of the Tiaojishan Formation, which have been dated to 160.89 to 160.25 million years ago,[5] or the Oxfordian stage of the Jurassic period.[1]

In 2017, the type and only species Douzhanopterus zhengi was named and described by Wang Xiaoli, Jiang Shunxing, Zhang Junqiang, Cheng Xin, Yu Xuefeng, Li Yameng, Wei Guangjin and Wang Xiaolin. The generic name combines the name Dòu-zhànshèng-fó (鬥戰勝佛, "Victorious Fighting Buddha"), which was given to the legendary Sun Wukong when he attained the status of Buddha, with the Latinised Greek pteron ("wing"). This is in reference to the animal occupying a more derived position relative to the wukongopterids. The specific name honours Professor Zheng Xiaoting.[1]

Classification

In 2017, Wang et al. assigned Douzhanopterus to the Monofenestrata. Douzhanopterus exhibits a number of characteristics that are intermediate between more basal pterosaurs, including the Wukongopteridae,[6][7][8][9] and the more derived Pterodactyloidea. In particular, the cervical vertebrae are generally longer; the tail is less than half of body length but still not particularly reduced; the metacarpals are moderately long compared to the humerus and ulna; and the fifth digit of the foot still bears two phalanges, although they are reduced with respect to basal pterosaurs but still larger than pterodactyloids. Its position in the phylogenetic tree recovered by Wang et al., the topology of which is partially reproduced below, is consistent with its intermediate condition.[1]

| Monofenestrata |

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

More derived than Douzhanopterus is the "Painten pro-pterodactyloid", an unnamed juvenile specimen from the Kimmeridgian of Germany.[10] They share a long fourth metacarpal, relatively reduced phalanges of the fifth digit on the foot, and a reduced but still relatively long tail with long zygapophyses and chevrons. However, several characteristics indicate that Douzhanopterus is still more basal: the pteroid is larger relative to the ulna, the tibia is much longer than the femur, the tail is longer both absolutely (22 vertebrate and longer than the femur, as opposed to the 17 in the Painten specimen) and relative to the humerus, and the zygapophyses and chevrons are slightly longer.[10] These differences are probably not related to the young age of the Painten specimen, based on studies of unpublished juvenile monofenestratan specimens.[1]

References

- Wang, X.; Jiang, S.; Zhang, J.; Cheng, X.; Yu, X.; Li, Y.; Wei, G.; Wang, X. (2017). "New evidence from China for the nature of the pterosaur evolutionary transition". Scientific Reports. 7: 42763. doi:10.1038/srep42763. PMC 5311862. PMID 28202936.

- Bennett, S.C. (1993). "The Ontogeny of Pteranodon and Other Pterosaurs". Paleobiology. 19 (1): 92–106. doi:10.1017/S0094837300012331. JSTOR 2400773.

- Kellner, A.W.A. (2015). "Comments on Triassic pterosaurs with discussion about ontogeny and description of new taxa". Anais da Academia Brasileira de Ciências. 87 (2): 667–689. doi:10.1590/0001-3765201520150307. ISSN 1678-2690. PMID 26131631.

- Bennett, S.C. (2013). "A new specimen of the pterosaur Scaphognathus crassirostris, with comments on constraint of cervical vertebrae number in pterosaurs". Neues Jahrbuch für Geologie und Paläontologie - Abhandlungen. 271 (3): 327–348. doi:10.1127/0077-7749/2014/0392.

- Chu, Z.; He, H.; Ramezani, J.; Bowring, S.A.; Hu, D.; Zhang, L.; Zheng, S.; Wang, X.; Zhou, Z.; Deng, C.; Guo, J. (2016). "High-precision U-Pb geochronology of the Jurassic Yanliao Biota from Jianchang (western Liaoning Province, China): Age constraints on the rise of feathered dinosaurs and eutherian mammals". Geochemistry, Geophysics, Geosystems. 17 (10): 3983–3992. doi:10.1002/2016GC006529.

- Wang, X.; Kellner, A.W.A.; Jiang, S.; Meng, Xi (2009). "An unusual long-tailed pterosaur with elongated neck from western Liaoning of China". Anais da Academia Brasileira de Ciências. 81 (4): 793–812. doi:10.1590/S0001-37652009000400016. ISSN 1678-2690. PMID 19893903.

- Lu, J.; Unwin, D.M.; Jin, X.; Liu, Y.; Ji, Q. (2010). "Evidence for modular evolution in a long-tailed pterosaur with a pterodactyloid skull". Proceedings of the Royal Society B. 277 (1680): 383–389. doi:10.1098/rspb.2009.1603. PMC 2842655. PMID 19828548.

- Wang, X.; Kellner, A.W.A.; Jiang, S.; Cheng, X.; Meng, X.; Rodrigues, T. (2010). "New long-tailed pterosaurs (Wukongopteridae) from western Liaoning, China". Anais da Academia Brasileira de Ciências. 82 (4): 1045–1062. doi:10.1590/S0001-37652010000400024. ISSN 0001-3765. PMID 21152776.

- Lu, J.; Xu, L.; Chang, H.; Zhang, X. (2011). "A New Darwinopterid Pterosaur from the Middle Jurassic of Western Liaoning, Northeastern China and its Ecological Implications". Acta Geologica Sinica. 85 (3): 507–514. doi:10.1111/j.1755-6724.2011.00444.x.

- Tischlinger, T.; Frey, E. (2013). "A new pterosaur with mosaic characters of basal and pterodactyloid pterosauria from the Upper Kimmeridgian of Painten (Upper Palatinate, Germany)". Archaeopteryx. 31: 1–13.