Bellubrunnus

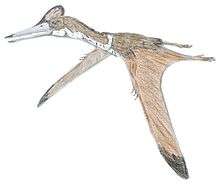

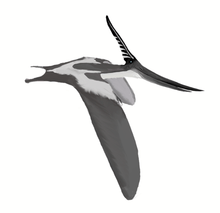

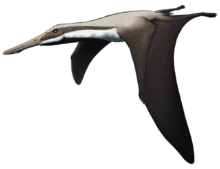

Bellubrunnus (meaning "the beautiful one of Brunn" in Latin) is an extinct genus of rhamphorhynchid pterosaur from the Late Jurassic (Kimmeridgian stage) of southern Germany. It contains a single species, Bellubrunnus rothgaengeri. Bellubrunnus is distinguished from other rhamphorhynchids by its lack of long projections on the vertebrae of the tail, fewer teeth in the jaws, and wingtips that curve forward rather than sweep backward as in other pterosaurs.[1]

| Bellubrunnus | |

|---|---|

| |

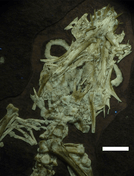

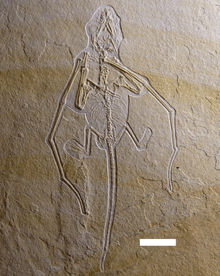

| The holotype specimen of Bellubrunnus, BSP–1993–XVIII–2 | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Order: | †Pterosauria |

| Family: | †Rhamphorhynchidae |

| Subfamily: | †Rhamphorhynchinae |

| Genus: | †Bellubrunnus Hone et al., 2012 |

| Type species | |

| †Bellubrunnus rothgaengeri Hone et al., 2012 | |

Discovery

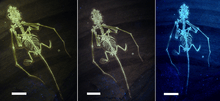

Bellubrunnus is known from a single complete articulated skeleton, the holotype of the genus, having the accession number BSP–1993–XVIII–2. It was found in the summer of 2002 by an excavation team led by Monika Rothgaenger, the namesake of the species. It was prepared in 2003 by Martin Kapitzke and at first identified as an exemplar of Rhamphorhynchus. It is preserved in ventral view, meaning that the underside of the skeleton can be seen on the limestone slab. The specimen is currently housed in the Bürgermeister-Müller-Museum, although it is cataloged for, and a possession of, the Bayerische Staatssammlung für Paläontologie und historische Geologie. It comes from a quarry at Kohlstatt near the village of Brunn, Upper Palatinate, in a layer of rock that underlies the better-known Solnhofen Limestone. The quarry dates to the late Kimmeridgian stage of the Late Jurassic period, about 151 million years ago. Ultraviolet lighting revealed many details of the fossil but showed no preserved soft tissues.[1]

Bellubrunnus was first described and named by David W. E. Hone, Helmut Tischlinger, Eberhard Frey and Martin Röper in 2012 and the type and only species is Bellubrunnus rothgaengeri. The generic name is derived from the Latin bellus meaning 'beautiful' and brunnus in reference to Brunn, its type locality. The combination then means 'the beautiful one of Brunn'. The specific name, rothgaengeri, honors Monika Rothgaenger for finding the holotype.[1]

Description

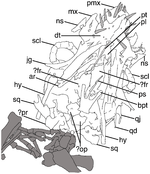

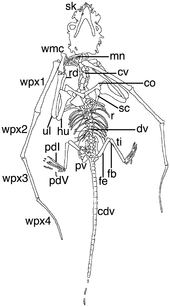

The holotype specimen of Bellubrunnus represents a small individual, with a wingspan of less than a foot, and is one of the smallest pterosaur fossils known. Nearly every bone is preserved in BSP–1993–XVIII–2, although no soft tissues have been found, neither as impressions nor as organic remains. The entire skeleton is complete except for missing parts of the right foot and tail tip. Because the skeleton is preserved in ventral view, many details of the skull ("sk" in the skeletal diagram) are obscured by the lower jaws (dentary, "dt" + angular, "ar" in the skull diagram). Many skull bones are also crushed and distorted, and some such as the maxillae ("mx"), nasal bones ("ns"), and sclerotic rings ("scl") are displaced. Part of the underside of the skull roof (perhaps the frontals, "?fr") can be seen among the bones of the lower jaws, palate (palatine bone, "pl" + pterygoid, "pt"), and braincase (parasphenoid, "ps" + basipterygoids, "bpt"). Twenty-one small teeth are preserved splaying out from the jaws. These were by the describers assumed to represent most of the original number, giving a total of twenty-two tooth positions — or twenty if a small element would be a replacement tooth — although it is not certain how they were divided between the upper jaws and the lower jaws. The teeth are elongated, straight, pointed and circular in cross-section. Although it is flattened on the slab, the skull is thought to have been tall at the back with a shortened snout. The eyes are very large relative to the size of the skull, occupying around a third of its total length. Both a shortened skull and large eyes are considered characteristics of juvenile pterosaurs, and other features, such as unfused skull bones and poorly ossified limb bones, suggest that BSP–1993–XVIII–2 was an immature individual when it died. The unfused scapulocoracoid bone — with the straight scapula ("sc") and coracoid ("co") still separate — in the pectoral girdle suggests that it may have been less than one year old.

The tooth number of twenty-two or less was indicated as an autapomorphy, or unique derived trait, of Bellubrunnus. Several distinguishing features are also present in the limbs of Bellubrunnus. The large hatchet-shaped deltopectoral crest of the humerus ("hu") or upper arm bone, in this case more precisely in the form of a rounded tongue, is one of the features that indicate that Bellubrunnus is a member of Rhamphorhynchidae, but the great length of the humerus in comparison to the length of the femur ("fe") or upper leg bone, with a ratio of 1.4, distinguishes it from other rhamphorhynchids and is a second autapomorphy. The humerus is also straight at the lower end, unlike the twisted humeri seen in other related pterosaurs, a third unique trait. A fourth autapomorphy is that the thighbone lacks a "neck" between its head and the shaft.[1] In terms of the proportions of limb bones, Bellubrunnus most closely resembles the rhamphorhynchid Rhamphorhynchus, which is also known from Germany.

Another distinguishing feature of Bellubrunnus is the shortness of its chevrons and zygapophyses on the caudal or tail vertebrae ("cdv"), indicating the tail was relatively flexible. In other rhamphorhynchids such as Dorygnathus, these bony projections are extremely elongated, and the zygapophyses are long enough to overlap a series of vertebrae behind them.

O'Sullivan and Martill (2015) found the majority of the purported distinguishing characters of Bellubrunnus to be problematic, stressing especially the lack of in-depth studies into the way rhamphorhynchid skeletons changed through ontogeny; this means that it remains uncertain whether the differences between Bellubrunnus and Rhamphorhynchus do indeed confirm that they are distinct taxa or whether these differences are merely ontogenetic in nature. The authors also noted that, given the severely crushed nature of the skull of Bellubrunnus, it is uncertain whether the number of teeth given by Hone et al. (2012) is indeed accurate, as more teeth may be covered by bone of missing from the holotype specimen. O'Sullivan and Martill found Bellubrunnus and Rhamphorhynchus to be similar enough for the former genus to be considered a junior synonym of the latter. The authors, however, noted that two characters of the species Bellubrunnus rothgaengeri (the lack of elongate caudal supports on the vertebrae and the anteriorly curving wing phalanx IV) make it possible that it is not conspecific with Rhamphorhynchus muensteri.[2]

Wings

In BSP–1993–XVIII–2, in both the left wing and the right wing the last finger bone or distal (fourth) phalanx bone ("wpx4") that supports the wing is curved, and preserved curving forward. The describers interpreted this as the natural position, assuming the third phalanx of the right wing finger ("wpx3") and most of the left wing finger had rotated 180° along their long axes relative to the fourth phalanges, as indicated by the orientation of the joint surfaces. Awaiting confirmation by a second specimen, the trait has not been formally indicated as an autapomorphy. Some other pterosaurs have curved distal phalanges, but in most cases the curvature is thought to have been the result of fractured bones or developmental problems specific to the individuals with this feature, and they always curve backwards. Although their exact function is unknown, curved wingtips, inducing instability by increased air resistance and turbulence, may have allowed Bellubrunnus to maneuver itself better in the air. They also may, in combination with a different orientation of the actinofibrils of the wing membrane, have stabilized the soft tissue flaps at the ends of the wings, which were expanded in most pterosaurs and may have been prone to fluttering.[1]

Classification

Bellubrunnus was assigned to the Rhamphorhynchidae and more precisely to the Rhamphorhynchinae.

Paleoecology

The stratigraphic unit in the Brunn quarry where the Bellubrunnus holotype was found is almost identical to the Solnhofen Limestone, but slightly older. Like the Solnhofen, the Brunn limestones were likely laid down in the lagoons and reefs of an island region. It is similar to the Solnhofen in that it preserves fossils of land-living flora and fauna alongside marine organisms. Brunn lacks many of the reptiles that have been found from Solnhofen, and while many specimens of Rhamphorhynchus have been found in the Solnhofen Limestone, the single Bellubrunnus specimen is the only known pterosaur from Brunn. Bellubrunnus may have occupied the same ecological niche as Rhamphorhynchus, that of a piscivore or fish-eater, and may even have been its direct evolutionary ancestor, forming a chronogenus relation within a single persisting population, although more fossils are needed to confirm this relationship.[1]

References

- Hone, D. W. E.; Tischlinger, H.; Frey, E.; Röper, M. (2012). Claessens, Leon (ed.). "A New Non-Pterodactyloid Pterosaur from the Late Jurassic of Southern Germany". PLoS ONE. 7 (7): e39312. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0039312. PMC 3390345. PMID 22792168.

- Michael O'Sullivan and David M. Martill (2015). "Evidence for the presence of Rhamphorhynchus (Pterosauria: Rhamphorhynchinae) in the Kimmeridge Clay of the UK". Proceedings of the Geologists' Association. 126 (3): 390–401. doi:10.1016/j.pgeola.2015.03.003.