Parapsicephalus

Parapsicephalus (meaning "beside arch head") is a genus of long-tailed rhamphorhynchid pterosaurs from the Lower Jurassic Whitby, Yorkshire, England. It contains a single species, P. purdoni, named initially as a species of the related rhamphorhynchid Scaphognathus in 1888 but moved to its own genus in 1919 on account of a unique combination of characteristics. In particular, the top surface of the skull of Parapsicephalus is convex, which is otherwise only seen in dimorphodontians. This has been the basis of its referral to the Dimorphodontia by some researchers, but it is generally agreed upon that Parapsicephalus probably represents a rhamphorhynchid. Within the Rhamphorhynchidae, Parapsicephalus has been synonymized with the roughly contemporary Dorygnathus; this, however, is not likely given the many differences between the two taxa, including the aforementioned convex top surface of the skull. Parapsicephalus has been tentatively referred to the Rhamphorhynchinae subgrouping of rhamphorhynchids, but it may represent a basal member of the group instead.

| Parapsicephalus | |

|---|---|

| |

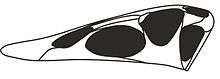

| Fossil skull showing brain endocast (AMNH 1694) | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Order: | †Pterosauria |

| Family: | †Rhamphorhynchidae |

| Genus: | †Parapsicephalus Arthaber, 1919 |

| Type species | |

| †Scaphognathus purdoni Newton, 1888 | |

| Species | |

| |

| Synonyms | |

| |

Description

The type skull of Parapsicephalus, which is 14 centimetres (5.5 in) long as preserved, suggests that it was of medium size.[1] Comparisons with the related pterosaurs Scaphognathus, Dorygnathus, and Jianchangnathus indicates that the full skull would have been 18–19.6 centimetres (7.1–7.7 in) long.[1][2][3] Wellnhofer estimated its wingspan at 1 metre (3 ft 3 in);[4] more recently, a referred humerus, which is 10 centimetres (3.9 in) long, has produced wingspan estimates of 1.68–3.26 metres (5 ft 6 in–10 ft 8 in).[5]

Skull

When viewed from the side, the convex top of the skull formed a gentle slope. The elongate frontal process of the premaxilla, which extends backwards towards the eyes, may have supported a low crest along its midline.[6] Below the nostril, the premaxilla meets with the maxilla; their junction is marked by a discontinuity in the surface texture of the bone. Overall, the oval-shaped antorbital fenestra, situated behind and separate from the nostril, measures 45 millimetres (1.8 in) long and 24 millimetres (0.94 in) tall. The maxilla extends backwards in a half-moon shape to encircle the front end of the fenestra, with the top prong of the maxilla forming a 45° angle with the horizontal. The top end of the fenestra is enclosed by the thin, rectangular, and slightly concave nasal, and the lacrimal, which is not well-preserved but may have been long, slender, and triangular. On the underside of the skull, the maxilla forms the majority of the palate (not the premaxilla, as previously assumed[7]), extending back from below the external nostrils. Along the midline of the maxilla is situated a thin strip of bone, the vomer, which connects back to join the pterygoid.[1]

At the back of the antorbital fenestra is the jugal, which has often been illustrated as a small V-shaped, two-pronged structure,[7] but it is actually large and has four prongs. The lacrimal process extends 20 millimetres (0.79 in) forward and upward from the main body of the jugal, while the more robust postorbital process extends 18 millimetres (0.71 in) backward and upward. Collectively, they enclose the bottom of the eye socket, with angles of 45° on each side. The pear-shaped eye socket measures 34 millimetres (1.3 in) tall and 32 millimetres (1.3 in) wide at the widest point. Behind the jugal is the quadratojugal, which has traditionally been depicted as hypertrophied and occupying the location of the back portion of the jugal;[7] it is actually a small, half moon-shaped bone wedged between the jugal and the quadrate and situated below the elongate infratemporal fenestra. Overall, the infratemporal fenestra is shaped similarly to the eye socket. The quadrates are strap-like, and wrap around from the back to the bottom of the skull. Although mostly obscured, the removal of the parietal during preparation has exposed part of the endocast of the brain, which has a large flocculus and cerebrum.[1]

The frontal, which is located on the top of the skull between the premaxilla and the eye socket, takes the shape of a sub-rectangle with a large, rhombic process extending forward to meet the nasal. The frontal process of the premaxilla cuts into the frontal along the midline of this rhombus. Contacting the rear ends of both the frontal and jugal is the thin and triangular postorbital, about 15 millimetres (0.59 in) long along the bottom, extends backwards to separate the infratemporal and supratemporal fenestrae. The supratemporal fenestra itself is a somewhat four-sided oval. Behind the postorbital and closing off the supratemporal fenestra is the three-pronged squamosal, which is partially overlapped by the robust, spatula-like paroccipital processes of the occipital. Between the processes is the foramen magnum, which is a 7 millimetres (0.28 in) oval. Further below is the basoccipital, which forms a rounded plate that encloses the back of the skull.[1]

Referred pectoral girdle

The humerus referred to Parapsicephalus probably had a slightly deflected deltopectoral crest. It bears a sub-triangular medial process, 7 millimetres (0.28 in) wide and 25 millimetres (0.98 in) long, that originates close to the humeral head. In cross-section, the shaft of the humerus is sub-rectangular, and about 7 millimetres (0.28 in) wide at the midpoint; the bottom third of the shaft is bowed forward. The scapula and coracoid appear to be completely fused; they are respectively 67 millimetres (2.6 in) and 59 millimetres (2.3 in) long, and form an angle of 70° to each other, creating overall a V-shaped structure as in Sericipterus.[8] The outer end of the scapula is noticeably wider than the inner end, and the glenoid is positioned entirely on the scapula, with the shaft curving about 15° towards the glenoid. Meanwhile, the portion of the coracoid closest to the glenoid is very expanded.[5]

Discovery and naming

Parapsicephalus is only definitely known from a single partial skull lacking the snout, but including a detailed endocast of the brain. It is catalogued under the specimen number GSM 3166, and is stored at the British Geological Survey in Keyworth, Nottinghamshire. It was collected in the 1880s by Reverend D.W. Purdon from the Loftus Alum Shale Quarry, in Loftus, North Yorkshire,[9][10] from which fossils had been discovered as early as the early nineteenth century.[11] The quarry has since become disused since operations ceased in 1860. The exposed rocks, which consist of pyrite-rich shales with calcareous concretions,[10] are part of the upper Alum Shale Member of the Whitby Mudstone Formation, which has been dated to about 182 million years ago, or the Toarcian stage of the Jurassic period.[1]

GSM 3166 was described by Edwin Tulley Newton, who loaned it from Rev. Purdon, in 1888. He described it as a species of Scaphognathus, S. purdoni, named after Purdon; he did not include it in the type species S. crassirostris due to differences in the curvature of the top of the skull, as well as the midline channel on the top of the skull. In his description of the braincase, he noted its intermediate morphology between that of lizards and birds, which he considered evidence of a close relationship between birds, pterosaurs, and "reptiles".[7] F. Plieninger subsequently compared GSM 3166 to Campylognathoides, and expressed that it was not as close to Scaphognathus as Newton had presumed.[12] Later, in 1919, Gustav von Arthaber, based on the shape of the top of the skull, the elongated nostrils and prefrontal bones, the large antorbital fenestra and eye socket, the deep jugal, and the presence of seven teeth in the maxilla, referred GSM 3166 to the new genus Parapsicephalus.[1][13]

Possible synonymy with Dorygnathus

In 2003, David Unwin, Kenneth Carpenter, and others suggested that Parapsicephalus was actually closer to the roughly contemporaneous Dorygnathus from German deposits. Unwin formally renamed it to the new combination Dorygnathus purdoni.[14][15][16] This renaming was adopted by some researchers[17][18] but not others.[2][19][20][21] However, a 2017 redescription of GSM 3166 noted a number of ways in which Dorygnathus differed from Parapsicephalus: the greater angle of the lacrimal process of the maxilla, the more reduced maxillary process of the premaxilla, the broader angle of the jugal beneath the eye socket, the overall thinner jugal relative to skull height, the more rounded the eye socket, the more oval-shaped supratemporal fenestra, and the convex top of the skull (which is unique among pterosaurs except for dimorphodontians). On the basis of these characteristics, the study recognized Parapsicephalus as a distinct genus.[1]

Possible additional specimens

The specimen NHMUK PV R36634 was found in 2011 within a concretion in Saltwick Bay, which also belongs to the Alum Shale Member.[1] It consists of a scapula, coracoid, and humerus; the head of the humerus was broken off during excavation as a result of the concretion being hammered open (which is the usual method for exposing ammonites preserved in concretions). Although it is impossible to refer this specimen to Parapsicephalus with confidence, its provenance and similarity to Dorygnathus were the basis of the tentative identification of the specimen as belonging to this genus.[5] An additional possible specimen is a skull collected in 1994 from Altdorf, Bavaria, Germany, which bears great similarity to GSM 3166 and also preserves some additional elements. It is currently held by a private collector, but will soon be donated to an institution in the UK.[1]

Classification

Although Newton originally considered Parapsicephalus as being a species of Scaphognathus,[7] Arthaber remarked that it was actually more similar to Dimorphodon instead.[13] The prevailing view since Arthaber's renaming of Parapsicephalus as a distinct genus has been that Parapsicephalus represents some kind of rhamphorhynchid,[14][19] although several phylogenies by Brian Andres and colleagues supported Arthaber's hypothesis of it being closely affiliated with Dimorphodon.[21][22] Characters which support this placement include the convex top of the skull, the pear-shaped eye socket, the angle of the quadrate, and the thick jugal.[21] The topology recovered by Andres and Myers in 2013, showing Parapsicephalus as a dimorphodontian, is reproduced below.[22]

| Pterosauria |

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

A 2017 analysis of Parapsicephalus found little support for it being placed in the Dimorphodontia: its skull was comparatively longer; the snout is slightly upturned with outward-projecting teeth, as in rhamphorhynchids; the quadrate is not as vertical; the antorbital fenestra is offset below the nostril instead of being at the same level; and, although the top of the skull is convex in both, the condition in Parapsicephalus is not quite as extreme. Thus, affinities with the Rhamphorhynchidae were considered more probable. Within the Rhamphorhynchidae, unlike the scaphognathines, the antorbital fenestra is more than twice as long as it is tall,[8][14] and has a concave back margin; the angle of the quadrate is also more than 120°.[23] This implies that Parapsicephalus is a member of the Rhamphorhynchinae.[1]

However, there are some factors that complicate a rhamphorhynchine position. In particular, the pear-shaped infratemporal fenestra and the overall size of the antorbital fenestra are more similar to scaphognathines than rhamphorhynchines. Additionally, like more basal non-rhamphorhynchid pterosaurs, there is a half moon-shaped process of the premaxilla extending beneath the nostril. It is thus possible that Parapsicephalus represents a basal rhamphorhynchid that is not in either group, which is not unexpected given its temporal context. The contemporary Allkaruen[24] is also a potentially viable subject of comparison, although its material and that of Parapsicephalus do not readily overlap.[1]

Paleoecology

The Alum Shale Member of the Whitby Mudstone Formation was probably deposited in an oxygen-poor, shallow-water environment.[10] A number of marine reptiles are known from this locality: the ichthyosaurs Stenopterygius, Temnodontosaurus, and Eurhinosaurus; the plesiosaurs Eretmosaurus, Sthenarosaurus, and Microcleidus; and the thalattosuchians Steneosaurus and Pelagosaurus. Indeterminate theropod remains have also been found.[1][9]

References

- O'Sullivan, M.; Martill, D.M. (2017). "The taxonomy and systematics of Parapsicephalus purdoni (Reptilia: Pterosauria) from the Lower Jurassic Whitby Mudstone Formation, Whitby, U.K". Historical Biology. 29 (8): 1009–1018. doi:10.1080/08912963.2017.1281919.

- Bennett, S.C. (2013). "A new specimen of the pterosaur Scaphognathus crassirostris, with comments on constraint of cervical vertebrae number in pterosaurs". Neues Jahrbuch für Geologie und Paläontologie - Abhandlungen. 271 (3): 327–348. doi:10.1127/0077-7749/2014/0392.

- Zhou, C.-F. (2014). "Cranial morphology of a Scaphognathus-like pterosaur, Jianchangnathus robustus, based on a new fossil from the Tiaojishan Formation of western Liaoning, China". Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology. 34 (3): 597–605. doi:10.1080/02724634.2013.812100.

- Wellnhofer, Peter (1996) [1991]. The Illustrated Encyclopedia of Pterosaurs. New York: Barnes and Noble Books. pp. 77–78. ISBN 978-0-7607-0154-6.

- O'Sullivan, M.; Martill, D.M.; Groodcock, D. (2013). "A pterosaur humerus and scapulocoracoid from the Jurassic Whitby Mudstone Formation, and the evolution of large body size in early pterosaurs". Proceedings of the Geologists' Association. 124 (6): 973–981. doi:10.1016/j.pgeola.2013.03.002.

- Dalla Vecchia, F.M.; Wild, R.; Hopf, H.; Reitner, J. (2002). "A Crested Rhamphorhynchoid Pterosaur from the Late Triassic of Austria". Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology. 22 (1): 196–199. doi:10.1671/0272-4634(2002)022[0196:acrpft]2.0.co;2. JSTOR 4524213.

- Newton, E.T. (1888). "On the skull, brain, and auditory organ of a new species of pterosaurian (Scaphognathus purdoni) from the Upper Lias near Whitby, Yorkshire". Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society of London B. 179: 503–537. doi:10.1098/rstb.1888.0019.

- Andres, B.; Clark, J.M.; Xu, X. (2010). "A new rhamphorhynchid pterosaur from the Upper Jurassic of Xinjiang, China, and the phylogenetic relationships of basal pterosaurs" (PDF). Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology. 30 (1): 163–187. doi:10.1080/02724630903409220.

- Benton, M.J.; Spencer, P.S. (1995). "British Early Jurassic fossil reptile sites". Fossil Reptiles of Great Britain. Geological Review Series. 10. London: Chapman and Hall. pp. 97–121. doi:10.1007/978-94-011-0519-4. ISBN 978-94-010-4231-4.

- Simms, M.J. (2004). "British Lower Jurassic stratigraphy: an introduction" (PDF). British Lower Jurassic Stratigraphy. Geological Conservation Review. 30. Peterborough: Joint Nature Conservation Committee. pp. 3–45.

- Hunton, L. (1837). "Remarks on a section of the Upper Lias and Marlstone of Yorkshire, showing the limited vertical range of the species of Ammonites, and other Testacea, with their value as geological tests". Transactions of the Geological Society of London. 2: 215–220. doi:10.1144/transgslb.5.1.215.

- Plieninger, F. "Campylognathus zittelli, ein neuer Flugsaurier aus dem Oberen Lias Schwabens" [Campylognathus zitteli, a new pterosaur from the Upper Lias of Swabia]. Palaeontographica (in German). 41: 193–222.

- Arthaber, G. (1919). "Studien über Flugsaurier auf Grund der Bearbeitung des Wiener exemplars von Dorygnathus banthensis Theod sp" [Studies in pterosaurs from the processing of Viennese examples of Dorygnathus banthensis Theod sp.] (PDF). Thoughts from the Mathematical-Natural Science Section of the Imperial Academy of Science, Vienna. 97: 391–464.

- Unwin, D.M. (2003). "On the phylogeny and evolutionary history of pterosaurs". Geological Society, London, Special Publications. 217: 136–190. doi:10.1144/GSL.SP.2003.217.01.11.

- Unwin, D.M. (2005). The Pterosaurs: From Deep Time. New York: Pi Press. p. 272. ISBN 978-0131463080.

- Carpenter, K.; Unwin, D.; Cloward, K.; Miles, C.; Miles, C. (January 2003). "A new scaphognathine pterosaur from the Upper Jurassic Morrison Formation of Wyoming, USA". Geological Society, London, Special Publications. 217 (1): 45–54. doi:10.1144/GSL.SP.2003.217.01.04.

- Hone, D.W.E.; Benton, M.J. (2007). "An evaluation of the phylogenetic relationships of the pterosaurs among archosauromorph reptiles" (PDF). Journal of Systematic Palaeontology. 5 (4): 465–469. doi:10.1017/S1477201907002064.

- Barrett, P.M.; Butler, R.J.; Edwards, N.P.; Milner, A.R. (2008). "Pterosaur distribution in time and space: an atlas" (PDF). Zitteliana. B28: 61–107. ISSN 1612-4138.

- Gasparini, Z.; Fernandez, M.; de la Fuente, M. (2004). "A New Pterosaur from the Jurassic of Cuba". Palaeontology. 47 (4): 919–927. doi:10.1111/j.0031-0239.2004.00399.x.

- Osi, A.; Prondvai, E.; Frey, E.; Pohl, B. (2010). "New Interpretation of the Palate of Pterosaurs". Anatomical Record. 293 (2): 243–258. doi:10.1002/ar.21053. PMID 19957339.

- Andres, B.; Clark, J.; Xu, X. (2014). "The Earliest Pterodactyloid and the Origin of the Group". Current Biology. 24 (9): 1011–1016. doi:10.1016/j.cub.2014.03.030. PMID 24768054.

- Andres, B.; Myers, T. S. (2013). "Lone Star Pterosaurs". Earth and Environmental Science Transactions of the Royal Society of Edinburgh. 103 (3): 383–398. doi:10.1017/S1755691013000303.

- Lu, J.; Unwin, D.M.; Zhao, B.; Gao, C.; Shen, C. (2012). "A new rhamphorhynchid (Pterosauria: Rhamphorhynchidae) from the Middle/Upper Jurassic of Qinglong, Hebei Province, China" (PDF). Zootaxa. 3158: 1–19. doi:10.11646/zootaxa.3158.1.1.

- Codorniú, L.; Carabajal, A.P.; Pol, D.; Unwin, D.; Rauhut, O.W.M (2016). "A Jurassic pterosaur from Patagonia and the origin of the pterodactyloid neurocranium". PeerJ. 4: e2311. doi:10.7717/peerj.2311. PMC 5012331. PMID 27635315.