Chaoyangopteridae

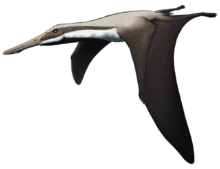

The Chaoyangopteridae are a family of pterosaurs within the Azhdarchoidea.

| Chaoyangopterids | |

|---|---|

| Holotype specimen of Jidapterus | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Order: | †Pterosauria |

| Suborder: | †Pterodactyloidea |

| Clade: | †Neoazhdarchia |

| Family: | †Chaoyangopteridae Lü et al., 2008 |

| Type species | |

| †Chaoyangopterus zhangi Wang & Zhou, 2003 | |

| Genera | |

The clade Chaoyangopteridae was first defined in 2008 by Lü Junchang and David Unwin as: "Chaoyangopterus, Shenzhoupterus, their most recent common ancestor and all taxa more closely related to this clade than to Tapejara, Tupuxuara or Quetzalcoatlus".[2] Based on neck and limb proportions, it has been suggested they occupied a similar ecological niche to that of azhdarchid pterosaurs,[3] though it is possible they were more specialised as several genera occur in Liaoning, while azhdarchids usually occur by one genus in a specific location. The Chaoyangopteridae are mostly known from Asia, though the possible member Lacusovagus occurs in South America[4] and there are possible fossil remains from Africa, including the possible member Apatorhamphus.[5] Microtuban may extend the clade's existence into the early Late Cretaceous.[6]

Chaoyangopterids are distinguished from other pterosaurs by several traits of the nasoantorbital fenestra, a large hole on the side of the snout formed by the assimilation of the nares (nostril holes) into the antorbital fenestra. In members of this family, the nasoantorbital fenestra is massive, with the rear edge extending as far back as the braincase and jaw joint. The front edge is formed by a rod of bone known as the premaxillary bar, which is unusually slender in members of this family.[2]

Like their azhdarchid relatives, chaoyangopterids were terrestrial predators.[6][7]

Classification

Below is a cladogram following Andres and Myers (2013).[8]

| Neoazhdarchia |

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

References

- Ross A. Elgin and Eberhard Frey (2011). "A new azhdarchoid pterosaur from the Cenomanian (Late Cretaceous) of Lebanon". Swiss Journal of Geosciences. in press. doi:10.1007/s00015-011-0081-1.

- Lü, Junchang; Unwin, David M.; Xu, Li; Zhang, Xingliao (2008-09-01). "A new azhdarchoid pterosaur from the Lower Cretaceous of China and its implications for pterosaur phylogeny and evolution". Naturwissenschaften. 95 (9): 891–897. doi:10.1007/s00114-008-0397-5. ISSN 1432-1904. PMID 18509616.

- http://pterosaur.net/species.php

- Witton, Mark P. (2008). "A new azhdarchoid pterosaur from the Crato Formation (Lower Cretaceous, Aptian?) of Brazil". Palaeontology. 51 (6): 1289–1300. doi:10.1111/j.1475-4983.2008.00811.x.

- James McPhee; Nizar Ibrahim; Alex Kao; David M. Unwin; Roy Smith; David M. Martill (2020). "A new ?chaoyangopterid (Pterosauria: Pterodactyloidea) from the Cretaceous Kem Kem beds of Southern Morocco". Cretaceous Research. in press: Article 104410. doi:10.1016/j.cretres.2020.104410.

- Wilton, Mark P. (2013). Pterosaurs: Natural History, Evolution, Anatomy. Princeton University Press. ISBN 0691150613.

- Wen-Hao Wu; Chang-Fu Zhou; Brian Andres (2017). "The toothless pterosaur Jidapterus edentus (Pterodactyloidea: Azhdarchoidea) from the Early Cretaceous Jehol Biota and its paleoecological implications". PLoS ONE. 12 (9): e0185486. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0185486.

- Andres, B.; Myers, T. S. (2013). "Lone Star Pterosaurs". Earth and Environmental Science Transactions of the Royal Society of Edinburgh: 1. doi:10.1017/S1755691013000303.