Cluster munition

A cluster munition is a form of air-dropped or ground-launched explosive weapon that releases or ejects smaller submunitions. Commonly, this is a cluster bomb that ejects explosive bomblets that are designed to kill personnel and destroy vehicles. Other cluster munitions are designed to destroy runways or electric power transmission lines, disperse chemical or biological weapons, or to scatter land mines. Some submunition-based weapons can disperse non-munitions, such as leaflets.

Because cluster bombs release many small bomblets over a wide area, they pose risks to civilians both during attacks and afterwards. Unexploded bomblets can kill or maim civilians and/or unintended targets long after a conflict has ended, and are costly to locate and remove.

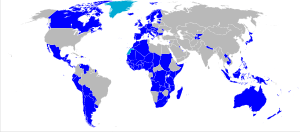

Cluster munitions are prohibited for those nations that ratify the Convention on Cluster Munitions, adopted in Dublin, Ireland in May 2008. The Convention entered into force and became binding international law upon ratifying states on 1 August 2010, six months after being ratified by 30 states.[1] As of 1 April 2018, a total of 120 states have joined the Convention, as 103 States parties and 17 Signatories.[2]

Development

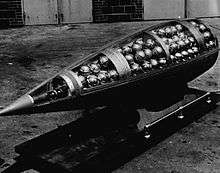

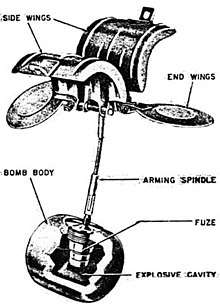

The first cluster bomb used operationally was the German SD-2 or Sprengbombe Dickwandig 2 kg, commonly referred to as the Butterfly Bomb.[3] It was used in World War II to attack both civilian and military targets. The technology was developed independently by the United States, Russia and Italy (see Thermos bomb). The US used the 20-lb M41 fragmentation bomb wired together in clusters of 6 or 25 with highly sensitive or proximity fuzes.

From the 1970s to the 1990s cluster bombs became standard air-dropped munitions for many nations, in a wide variety of types. They have been produced by 34 countries and used in at least 23.[4]

Artillery shells that employ similar principles have existed for decades. They are typically referred to as ICM (Improved Conventional Munitions) shells. The US military slang terms for them are "firecracker" or "popcorn" shells, for the many small explosions they cause in the target area.

Types

A basic cluster bomb consists of a hollow shell and then two to more than 2,000 submunitions or bomblets contained within it. Some types are dispensers that are designed to be retained by the aircraft after releasing their munitions. The submunitions themselves may be fitted with small parachute retarders or streamers to slow their descent (allowing the aircraft to escape the blast area in low-altitude attacks).

Modern cluster bombs and submunition dispensers can be multiple-purpose weapons containing a combination of anti-armor, anti-personnel, and anti-materiel munitions. The submunitions themselves may also be multi-purpose, such as combining a shaped charge, to attack armour, with a fragmenting case, to attack infantry, material, and light vehicles. They may also have an incendiary function.

Since the 1990s submunition-based weapons have been designed that deploy smart submunitions, using thermal and visual sensors to locate and attack particular targets, usually armored vehicles. Weapons of this type include the US CBU-97 sensor-fuzed weapon, first used in combat during Operation Iraqi Freedom, the 2003 invasion of Iraq. Some munitions specifically intended for anti-tank use can be set to self-destruct if they reach the ground without locating a target, theoretically reducing the risk of unintended civilian deaths and injuries. Although smart submunition weapons are much more expensive than standard cluster bombs, fewer smart submunitions are required to defeat dispersed and mobile targets, partly offsetting their cost. Because they are designed to prevent indiscriminate area effects and unexploded ordnance risks, these submunitions are not classified as cluster munitions under the Convention on Cluster Munitions.

Incendiary

Incendiary cluster bombs are intended to start fires, just like conventional incendiary bombs (firebombs). They contain submunitions of white phosphorus or napalm, and can be combined anti-personnel and anti-tank submunitions to hamper firefighting efforts. In urban areas they have been preceded by the use of conventional explosive bombs to fracture the roofs and walls of buildings to expose their flammable contents. One of the earliest examples is the so-called Molotov bread basket used by the Soviet Union in the Winter War of 1939–40. Incendiary clusters were extensively used by both sides in the strategic bombings of World War II. They caused firestorms and conflagrations in the bombing of Dresden in World War II and the firebombing of Tokyo. Some modern bomb submunitions deliver a highly combustible thermobaric aerosol that results in a high pressure explosion when ignited.

Anti-personnel

Anti-personnel cluster bombs use explosive fragmentation to kill troops and destroy soft (unarmored) targets. Along with incendiary cluster bombs, these were among the first types of cluster bombs produced by Nazi Germany during World War II. They were used during the Blitz with delay and booby-trap fusing to hamper firefighting and other damage-control efforts in the target areas. They were also used with a contact fuze when attacking entrenchments. These weapons were widely used during the Vietnam War when many thousands of tons of submunitions were dropped on Laos, Cambodia and Vietnam.[5]

Anti-tank

Most anti-armor munitions contain shaped charge warheads to pierce the armor of tanks and armored fighting vehicles. In some cases, guidance is used to increase the likelihood of successfully hitting a vehicle. Modern guided submunitions, such as those found in the U.S. CBU-97, can use either a shaped charge or an explosively formed penetrator. Unguided shaped-charge submunitions are designed to be effective against entrenchments that incorporate overhead cover. To simplify supply and increase battlefield effectiveness by allowing a single type of round to be used against nearly any target, submunitions that incorporate both fragmentation and shaped-charge effects are produced.

Mine-laying

Submunition-based mines do not detonate immediately, but behave like conventional land mines that detonate later. These submunitions usually include a combination of anti-personnel and anti-tank mines. Since such mines lie exposed on surfaces, the anti-personnel forms, such as the US Area Denial Artillery Munition normally deploy tripwires automatically after landing to make clearing the minefield more difficult. In order to avoid accumulating large areas of impassable battlefield, and to minimize the amount of mine-clearing needed after a conflict, scatterable mines used by the United States are designed to self-destruct after a period of time from 4 to 48 hours. The internationally agreed definition of cluster munitions being negotiated in the Oslo Process may not include this type of weapon, since landmines are already covered by other international treaties.

Chemical weapons

During the 1950s and 1960s, the United States and Soviet Union developed cluster weapons designed to deliver chemical weapons. The Chemical Weapons Convention of 1993 banned their use. Six member nations declared themselves in possession of chemical weapons. The US and Russia are still in the process of destroying their stockpiles, having received extensions of the time limit for full destruction. They were unable to complete the destruction of their chemical weapons stockpiles by 2007, as the Treaty originally required.

Anti-electrical

An anti-electrical weapon, the CBU-94/B, was first used by the U.S. in the Kosovo War in 1999. These consist of a TMD (Tactical Munitions Dispenser) filled with 202 BLU-114/B "Soft-Bomb" submunitions. Each submunition contains a small explosive charge that disperses 147 reels of fine conductive fiber of either carbon or aluminum-coated glass. Their purpose is to disrupt and damage electric power transmission systems by producing short circuits in high-voltage power lines and electrical substations. On the initial attack, these knocked out 70% of the electrical power supply in Serbia.

Leaflet dispensing

The LBU-30 is designed for dropping large quantities of propaganda leaflets from aircraft. Enclosing the leaflets within the bomblets ensures that the leaflets will fall on the intended area without being dispersed excessively by the wind. The LBU-30 consists of SUU-30 dispensers that have been adapted to leaflet dispersal. The dispensers are essentially recycled units from old bombs. The LBU-30 was tested at Eglin Air Force Base in 2000, by an F-16 flying at 20,000 feet (6,100 m).[6]

History of use

Vietnam War

During the Vietnam War, the US used cluster bombs in air strikes against targets in Vietnam, Laos, and Cambodia.[7] According to The Guardian, of the 260 million cluster bomblets that rained down on Laos between 1964 and 1973, particularly on Xieng Khouang province, 80 million failed to explode.[8] The GlobalPost reports that as of 2009 about 7,000 people have been injured or killed by explosives left from the Vietnam War era in the Vietnamese Quang Tri Province alone.[9]

Western Sahara war, 1975–1991

During the 16-year-long conflict on the territory of Western Sahara, the Royal Moroccan Army (RMA) dropped cluster bombs.

The RMA used both artillery-fired and air-dropped cluster munitions. BLU-63, M42 and MK118 submunitions were used at multiple locations in Bir Lahlou, Tifarity, Mehaires, Mijek and Awganit.

More that 300 cluster strike areas have been recorded in the MINURSO Mine Action Coordination Center database.

Soviet–Afghan War, 1979–1989

During the Soviet-Afghan War, Russia dealt harshly with Mujahideen rebels and those who supported them, to include, leveling entire villages to deny safe havens to their enemy and employing cluster bombs, As reported by Human Rights Watch, Afghanistan: The Forgotten War: Human Rights Abuses and Violations of the Laws of War Since the Soviet Withdrawal, 1 February 1991,

Falklands War

Sea Harriers of the Royal Navy dropped BL755 cluster bombs on Argentinian positions during the Falklands War of 1982.

Nagorno Karabakh War, 1992–1994, 2016

- Hundreds of cluster bombs were used by Azerbaijan in Nagorno Karabakh in 1992–94 in the course of the Nagorno-Karabakh War. As of 2010, 93 km2 remain off-limits due to contamination with unexploded cluster ordnance. HALO Trust has made major contributions to the cleanup effort.[10][11] The charity reported the use of cluster bombs by Azerbaijan during renewed hostilities in April 2016.[12]

First Chechen War, 1995

- Used by Russia, see also 1995 Shali cluster bomb attack

Yugoslavia, 1999

- Used by the US, the UK and Netherlands.

About 2,000 cluster bombs containing 380,000 sub-munitions were dropped on Yugoslavia during the Operation Allied Force, in 1999, of which the Royal Air Force dropped 531 RBL755 cluster bombs.[13][14]

On 7 May 1999, between the time of 11:30 and 11:40, a NATO attack was carried out with two containers of cluster bombs and fell in the central part of the city:

- The Pathology building next to the Medical Center of Nis in the south of the city,

- Next to the building of "Banovina" including the main market, bus station next to the Niš Fortress and "12th February" Health Centre

- Parking of "Niš Express" near river Nišava River.

Reports claimed that 15 civilians were killed, 8 civilians were seriously injured, 11 civilians had sustained minor injuries, 120 housing units were damaged and 47 were destroyed and that 15 cars were damaged.

Overall during the operation, at least 23 Serb civilians were killed by cluster munitions. At least six Serbs, including three children were killed by bomblets after the operation ended, and up to 23 square kilometres in six areas remain "cluster contaminated", according to Serbian government, including on Mt. Kopaonik near the slopes of the ski resort. The UK contributed £86,000 to the Serbian Mine Action Centre.[13]

Afghanistan, 2001–2002

Iraq

- Used by the United States and the United Kingdom

1991: United States, France, and the United Kingdom dropped 61,000 cluster bombs, containing 20 million submunitions, on Iraq, according to the HRW.[18]

2003–2006: United States and allies attacked Iraq with 13,000 cluster munitions, containing two million submunitions during Operation Iraqi Freedom, according to the HRW.[19] At multiple times, coalition forces used cluster munitions in residential areas, and the country remains among the most contaminated to this day, bomblets posing a threat to both US military personnel in the area, and local civilians.[20]

When these weapons were fired on Baghdad on April 7, 2003 many of the bomblets failed to explode on impact. Afterward, some of them exploded when touched by civilians. USA Today reported that "the Pentagon presented a misleading picture during the war of the extent to which cluster weapons were being used and of the civilian casualties they were causing." On April 26, General Richard Myers, chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff, said that the US had caused only one civilian casualty.[21]

Lebanon, 1978, 1982 and 2006

- Extensively used by Israel during the 1978 Israeli invasion of Lebanon, the 1982–2000 occupation of Lebanon and also by Hezbollah in the 2006 Lebanon War.

During the Israeli-Lebanese conflict in 1982, Israel used cluster munitions, many of them American-made, on targets in southern Lebanon. Israel also used cluster bombs in the 2006 Lebanon War.[22][23][24]

Two types of cluster munitions were transferred to Israel from the U.S. The first was the CBU-58 which uses the BLU-63 bomblet. This cluster bomb is no longer in production. The second was the MK-20 Rockeye, produced by Honeywell Incorporated in Minneapolis. The CBU-58 was used by Israel in Lebanon in both 1978 and 1982.[22] The Israeli Defense company Israel Military Industries also manufactures the more up-to-date M-85 cluster bomb.

Hezbollah fired Chinese-manufactured cluster munitions against Israeli civilian targets, using 122-mm rocket launchers during the 2006 war, hitting Kiryat Motzkin, Nahariya, Karmiel, Maghar, and Safsufa. A total of 113 rockets and 4,407 submunitions were fired into Israel during the war.[25][25][26]

According to the United Nations Mine Action Service, Israel dropped up to four million submunitions on Lebanese soil, of which one million remain unexploded.[27] According to a report prepared by Lionel Beehner for the Council on Foreign Relations, the United States restocked Israel's arsenal of cluster bombs, triggering a State Department investigation to determine whether Israel had violated secret agreements it had signed with the United States on their use.[27]

As Haaretz reported in November 2006, the Israel Defense Forces Chief of Staff Dan Halutz wanted to launch an investigation into the use of cluster bombs during the Lebanon war.[28] Halutz claimed that some cluster bombs had been fired against his direct order, which stated that cluster bombs should be used with extreme caution and not be fired into populated areas. The IDF apparently disobeyed this order.[28]

Human Rights Watch said there was evidence that Israel had used cluster bombs very close to civilian areas and described them as "unacceptably inaccurate and unreliable weapons when used around civilians" and that "they should never be used in populated areas."[29] Human Rights Watch has accused Israel of using cluster munitions in an attack on Bilda, a Lebanese village, on 19 July[30] which killed 1 civilian and injured 12, including seven children. The Israeli "army defended ... the use of cluster munitions in its offensive with Lebanon, saying that using such munitions was 'legal under international law' and the army employed them 'in accordance with international standards.'"[31] Foreign Ministry Spokesman Mark Regev added, "[I]f NATO countries stock these weapons and have used them in recent conflicts – in Yugoslavia, Afghanistan and Iraq – the world has no reason to point a finger at Israel."[32]

Georgia, 2008

- Georgia and Russia both were accused of using cluster munitions during the 2008 Russo-Georgian War. Georgia admitted use, Russia denied it.

Georgia admitted using cluster bombs during the war, according to Human Rights Watch.[34] The Georgian army used LAR-160 multiple rocket launchers to fire MK4 LAR 160 type rockets (with M-85 bomblets) with a range of 45 kilometers the Georgian Minister of Defense (MoD) said.[35]

According to the Human Rights Watch, the Russian Air Force used RBK-250 cluster bombs during the conflict.[36] A high-ranking Russian military official denied use of cluster bombs.[37] The Dutch government, after investigating the death of a Dutch citizen, concluded that a cluster munition was propelled by an 9K720 Iskander tactical missile (used by Russia at the time of conflict, and not used by Georgia).[38]

Libya, 2011

It was reported in April 2011 that Colonel Gaddafi's forces had used cluster bombs in the conflict between government forces and rebel forces trying to overthrow Gaddafi's government, during the battle of Misrata[39] These reports were denied by the government, and the Secretary of State of the US,[40] Hillary Clinton said she was "not aware" of the specific use of cluster or other indiscriminate weapons in Misurata even though a New York Times investigation refuted those claims.[41] An ejection canister for a Type 314 A AV submunition, manufactured in France was found in Libya despite the fact that France is a party to the international convention that bans cluster munitions.

Syria, 2012

During the Syrian uprising, a few videos of cluster bombs first appeared in 2011, but escalated in frequency near the end of 2012.[42][43] As Human Rights Watch reported on October 13, 2012, "Eliot Higgins, who blogs on military hardware and tactics used in Syria under the pseudonym "Brown Moses", compiled a list of the videos showing cluster munition remnants in Syria's various governorates."[42][43] The type of bombs have been reported to be RBK-250 cluster bombs with AO-1 SCH bomblets (of Soviet design).[43] Designed by the Soviet Union for use on tank and troop formations, PTAB-2.5M bomblets were used on civilian targets in Mare' in December 2012 by the Syrian government.[44] According to the seventh annual Cluster Munition Report, there is ″compelling evidence″ that Russia has used cluster muntions during their involvement in Syria.[45]

South Sudan, 2013

Cluster bombs remnants were discovered by a UN de-mining team in February 2014 on a section of road near the Jonglei state capital, Bor. The strategic town was the scene of heavy fighting, changing hands several times during the South Sudanese Civil War, which erupted in the capital Juba on 15 December 2013 before spreading to other parts of the country. According to the United Nations Mine Action Service (UNMAS), the site was contaminated with the remnants of up to eight cluster bombs and an unknown quantity of bomblets.[46]

Ukraine, 2014

Human Rights Watch reported that "Ukrainian government forces used cluster munitions in populated areas in Donetsk city in early October 2014."[47]

Yemen, 2015

British-supplied[48] and U.S.-supplied cluster bombs[49] have been used by Saudi Arabian-led military coalition against Houthi militias in Yemen, according to Human Rights Watch and Amnesty International.[50][51][52]

Saudi Arabia is not signatory to the Convention on Cluster Munitions.[53]

Threat to civilians

While all weapons are dangerous, cluster bombs pose a particular threat to civilians for two reasons: they have a wide area of effect, and they have consistently left behind a large number of unexploded bomblets. The unexploded bomblets can remain dangerous for decades after the end of a conflict. For example, while the United States cluster bombed Laos only until 1973, unexploded munitions continue to cause over 100 casualties per year to Laos civilians.[54]

Cluster munitions are opposed by many individuals and hundreds of groups, such as the Red Cross,[55] the Cluster Munition Coalition and the United Nations, because of the high number of civilians that have fallen victim to the weapon. Since February 2005, Handicap International called for cluster munitions to be prohibited and collected hundreds of thousands of signatures to support its call.[56] 98% of 13,306 recorded cluster munitions casualties that are registered with Handicap International are civilians, while 27% are children.[57]

The area affected by a single cluster munition, known as its footprint, can be very large; a single unguided M26 MLRS rocket can effectively cover an area of 0.23 km2.[58] In US and most allied services, the M26 has been replaced by the M30 guided missile fired from the MLRS. The M30 has greater range and accuracy but a smaller area of coverage. It is worth noting that for reasons including both danger to civilians and changing tactical requirements, the non-cluster unitary warhead XM31 missile is, in many cases, replacing even the M30.

Because of the weapon's broad area of effect, they have often been documented as striking both civilian and military objects in the target area. This characteristic of the weapon is particularly problematic for civilians when cluster munitions are used in or near populated areas and has been documented by research reports from groups such as Human Rights Watch,[59] Landmine Action, Mines Action Canada and Handicap International. In some cases, like the Zagreb rocket attack, civilians were deliberately targeted by such weapons.[60]

Unexploded ordnance

The other serious problem, also common to explosive weapons is unexploded ordnance (UXO) of cluster bomblets left behind after a strike. These bomblets may be duds or in some cases the weapons are designed to detonate at a later stage. In both cases, the surviving bomblets are live and can explode when handled, making them a serious threat to civilians and military personnel entering the area. In effect, the UXOs can function like land mines.

Even though cluster bombs are designed to explode prior to or on impact, there are always some individual submunitions that do not explode on impact. The US-made MLRS with M26 warhead and M77 submunitions are supposed to have a 5% dud rate but studies have shown that some have a much higher rate.[61] The rate in acceptance tests prior to the Gulf War for this type ranged from 2% to a high of 23% for rockets cooled to −25 °F (−32 °C) before testing.[62] The M483A1 DPICM artillery-delivered cluster bombs have a reported dud rate of 14%.[63]

Given that each cluster bomb can contain hundreds of bomblets and be fired in volleys, even a small failure rate can lead each strike to leave behind hundreds or thousands of UXOs scattered randomly across the strike area. For example, after the 2006 Israel-Lebanon conflict, UN experts have estimated that as many as one million unexploded bomblets may contaminate the hundreds of cluster munition strike sites in Lebanon.[64]

In addition, some cluster bomblets, such as the BLU-97/B used in the CBU-87, are brightly colored to increase their visibility and warn off civilians. However, the yellow color, coupled with their small and nonthreatening appearance, is attractive to young children who wrongly believe them to be toys. This problem was exacerbated in the War in Afghanistan (2001–present), when US forces dropped humanitarian rations from airplanes with similar yellow-colored packaging as the BLU-97/B, yellow being the NATO standard colour for high explosive filler in air weapons. The rations packaging was later changed first to blue and then to clear in the hope of avoiding such hazardous confusion.

The US military is developing new cluster bombs that it claims could have a much lower (less than 1%) dud rate.[65] Sensor-fused weapons that contain a limited number of submunitions that are capable of autonomously engaging armored targets may provide a viable, if costly, alternative to cluster munitions that will allow multiple target engagement with one shell or bomb while avoiding the civilian deaths and injuries consistently documented from the use of cluster munitions. Certain such weapons may be allowed under the recently adopted Convention on Cluster Munitions, provided they do not have the indiscriminate area effects or pose the unexploded ordnance risks of cluster munitions.

In the 1980s the Spanish firm Esperanza y Cia developed a 120mm caliber mortar bomb which contained 21 anti-armor submunitions. What made the 120mm "Espin" unique was the electrical impact fusing system which totally eliminated dangerous duds. The system operates on a capacitor in each submunition which is charged by a wind generator in the nose of the projectile after being fired. If for what ever reason the electrical fuse fails to function on impact, approximately 5 minutes later the capacitor bleeds out, therefore neutralizing the submunition's electronic fuse system.[66] Later a similar mortar round was offered in the 81mm caliber and equipped some Spanish Marine units. On signing the Wellington Declaration on Cluster Munitions, Spain withdrew both the 81mm and 120mm "Espin" rounds from its military units.

Civilian deaths

- In Vietnam, people are still being killed as a result of cluster bombs and other objects left by the US and Vietnamese military forces. Estimates range up to 300 people killed annually by unexploded ordnance.[67]

- Some 270 million cluster submunitions were dropped on Laos in the 1960s and 1970s; approximately one third of these submunitions failed to explode and continue to pose a threat today.[68]

- During the 1999 NATO war against Yugoslavia U.S. and Britain dropped 1,400 cluster bombs in Kosovo. Within the first year after the end of the war more than 100 civilians died from unexploded British and American bombs. Unexploded cluster bomblets caused more civilian deaths than landmines.[69]

- Israel used cluster bombs in Lebanon in 1978 and in the 1980s. Those weapons used more than two decades ago by Israel continue to affect Lebanon.[70] During the 2006 war in Lebanon, Israel fired large numbers of cluster bombs in Lebanon, containing an estimated more than 4 million cluster submunitions. In the first month following the ceasefire, unexploded cluster munitions killed or injured an average of 3–4 people per day.[71]

Locations

Countries and disputed territories (listed in italic) that have been affected by cluster munitions as of August 2019 include:[72]

- Afghanistan

- Angola

- Azerbaijan (mainly Nagorno Karabakh)

- Bosnia & Herzegovina

- Cambodia

- Chad

- Croatia

- Democratic Republic of the Congo

- Eritrea[73]

- Ethiopia[74]

- Germany

- Iran

- Iraq

- Laos

- Lebanon

- Libya

- Montenegro

- Serbia

- South Sudan

- Sudan

- Syria

- Tajikistan

- Ukraine

- United Kingdom (Falkland Islands)

- Vietnam

- Yemen

- Kosovo

- Western Sahara

As of August 2019, it is unclear, whether Colombia and Georgia are contaminated.[72] Albania, the Republic of the Congo, Grenada, Guinea-Bissau, Mauritania, Mozambique, Norway, Zambia, Uganda, and Thailand completed clearance of areas contaminated by cluster munition remnants in previous years.[72]

International legislation

Cluster bombs fall under the general rules of international humanitarian law, but were not specifically covered by any currently binding international legal instrument until the signature of the Convention on Cluster Munitions in December 2008. This international treaty stemmed from an initiative by the Government of Norway known as the Oslo Process which was launched in February 2007 to prohibit cluster munitions.[75] More than 100 countries agreed to the text of the resulting Convention on Cluster Munitions in May 2008 which sets out a comprehensive ban on these weapons. This treaty was signed by 94 states in Oslo on 3–4 December 2008. The Oslo Process was launched largely in response to the failure of the Convention on Certain Conventional Weapons (CCW) where five years of discussions failed to find an adequate response to these weapons.[76] The Cluster Munition Coalition (CMC) is campaigning for the widespread accession to and ratification of the Convention on Cluster Munitions.

A number of sections of the Protocol on explosive remnants of war (Protocol V to the 1980 Convention), 28 November 2003[77] occasionally address some of the problems associated with the use of cluster munitions, in particular Article 9, which mandates States Parties to "take generic preventive measures aimed at minimising the occurrence of explosive remnants of war". In June 2006, Belgium was the first country to issue a ban on the use (carrying), transportation, export, stockpiling, trade and production of cluster munitions,[78] and Austria followed suit on 7 December 2007.[4]

There has been legislative activity on cluster munitions in several countries, including Austria, Australia, Denmark, France, Germany, Luxembourg, Netherlands, Norway, Sweden, Switzerland, United Kingdom and United States. In some of these countries, ongoing discussions concerning draft legislation banning cluster munitions, along the lines of the legislation adopted in Belgium and Austria will now turn to ratification of the global ban treaty. Norway and Ireland have national legislation prohibiting cluster munitions and were able to deposit their instruments of ratification to the Convention on Cluster Munitions immediately after signing it in Oslo on 3 December 2008.

International treaties

Other weapons, such as land mines, have been banned in many countries under specific legal instruments for several years, notably the Ottawa Treaty to ban land mines, and some of the Protocols in the Convention on Certain Conventional Weapons that also help clearing the lands contaminated by left munitions after the end of conflicts and provides international assistance to the affected populations. However, until the recent adoption of the Convention on Cluster Munitions in Dublin in May 2008 cluster bombs were not banned by any international treaty and were considered legitimate weapons by some governments.

To increase pressure for governments to come to an international treaty on November 13, 2003, the Cluster Munition Coalition (CMC) was established with the goal of addressing the impact of cluster munitions on civilians. At the launch, organised by Pax Christi Netherlands, the then Minister of Foreign Affairs, the later Secretary General of NATO, Jaap de Hoop Scheffer, addressed the crowd of gathered government, NGO, and press representatives.

International governmental deliberations in the Convention on Certain Conventional Weapons turned on the broader problem of explosive remnants of war, a problem to which cluster munitions have contributed in a significant way. There were consistent calls from the Cluster Munition Coalition, the International Committee of the Red Cross (ICRC) and a number of UN agencies, joined by approximately 30 governments, for international governmental negotiations to develop specific measures that would address the humanitarian problems cluster munitions pose. This did not prove possible in the conventional multilateral forum. After a reversal in the US position, in 2007 deliberations did begin on cluster munitions within the Convention on Certain Conventional Weapons. There was a concerted effort led by the US to develop a new protocol to the Convention on Certain Conventional Weapons, but this proposal was rejected by over 50 states, together with civil society, ICRC and UN agencies.[79] The discussions ended with no result in November 2011, leaving the 2008 Convention on Cluster Munitions as the single international standard on the weapons.[80]

In February 2006, Belgium announced its decision to ban the weapon by law. Then Norway announced a national moratorium in June and Austria announced its decision in July to work for an international instrument on the weapon. The international controversy over the use and impact of cluster munitions during the war between Lebanon and Israel in July and August 2006 added weight to the global campaign for a ban treaty.[81]

Against this background, a new flexible multilateral process similar to the process that led to the ban on anti-personnel land mines in 1997 (the Ottawa Treaty) began with an announcement in November 2006[82] in Geneva as well at the same time by the Government of Norway that it would convene an international meeting in early 2007 in Oslo to work towards a new treaty prohibiting cluster munitions. Forty-nine governments attended the meeting in Oslo February 22–23, 2007 in order to reaffirm their commitment to a new international ban on the weapon. During the meeting Austria announced an immediate moratorium on the use, production and transfer of cluster munitions until a new international treaty banning the weapons is in place.

A follow-up meeting in this process was held in Lima in May where around 70 states discussed the outline of a new treaty, Hungary became the latest country to announce a moratorium and Peru launched an initiative to make Latin America a cluster munition free zone.[83]

In addition, the ICRC held an experts meeting on cluster munitions in April 2007 which helped clarify technical, legal, military and humanitarian aspects of the weapon with a view to developing an international response.[84]

Further meetings took place in Vienna on 4–7 December 2007, and in Wellington on 18–22 February 2008 where a declaration in favor of negotiations on a draft convention was adopted by more than 80 countries. In May 2008 after around 120 countries had subscribed to the Wellington Declaration and participated in the Dublin Diplomatic Conference from 19 to 30 May 2008. At the end of this conference, 107 countries agreed to adopt the Convention on Cluster Munitions, that bans cluster munitions and was opened for signature in Oslo on December 3–4, 2008 where it was signed by 94 countries.[85][86][87]

In July 2008, United States Defense Secretary Robert M. Gates implemented a policy to eliminate by 2018 all cluster bombs that do not meet new safety standards.[88]

In November 2008, ahead of the signing Conference in Oslo,[89] the European Parliament passed a resolution calling on all European Union governments to sign and ratify the Convention.[90]

On 16 February 2010 Burkina Faso became the 30th state to deposit its instrument of ratification for the Convention on Cluster Munitions. This means that the number of States required for the Convention to enter into force had been reached. The treaty's obligations became legally binding on the 30 ratifying States on 1 August 2010 and subsequently for other ratifying States.[91]

Convention on Cluster Munitions

Taking effect on August 1, 2010, the Convention on Cluster Munitions[92] bans the stockpiling, use and transfer of virtually all existing cluster bombs and provides for the clearing up of unexploded munitions. It had been signed by 108 countries, of which 38 had ratified it by the affected date, but many of the world's major military powers including the United States, Russia, Brazil and China are not signatories to the treaty.[93][94][95][96]

Ratifiers and signatories

The Convention on Cluster Munitions entered into force on 1 August 2010, six months after it was ratified by 30 states. As of 26 September 2018, a total of 120 states have joined the Convention, as 104 States parties and 16 signatories.[2]

For an updated list of countries, go to Convention on Cluster Munitions#States Parties

United States policy

In May 2008, then-Acting Assistant Secretary of State for Political-Military Affairs Stephen Mull stated that the U.S. military relies upon cluster munitions as an important part of their war strategy.

Cluster munitions are available for use by every combat aircraft in the U.S. inventory, they are integral to every Army or Marine maneuver element and in some cases constitute up to 50 percent of tactical indirect fire support. U.S. forces simply cannot fight by design or by doctrine without holding out at least the possibility of using cluster munitions.

— Stephen Mull

U.S. arguments favoring the use of cluster munitions are that their use reduces the number of aircraft and artillery systems needed to support military operations and if they were eliminated, significantly more money would have to be spent on new weapons, ammunition, and logistical resources. Also, militaries would need to increase their use of massed artillery and rocket barrages to get the same coverage, which would destroy or damage more key infrastructures. The U.S. was initially against any CCW negotiations but dropped its opposition in June 2007. Cluster munitions have been determined as needed for ensuring the country's national security interests, but measures were taken to address humanitarian concerns of their use, as well as pursuing their original suggested alternative to a total ban of pursuing technological fixes to make the weapons no longer viable after the end of a conflict.[97] In July 2012, the U.S. fired at a target area with 36 Guided Multiple Launch Rocket System (GMLRS) unitary warhead rockets. Analysis indicates that the same effects could have been made by four cluster GMLRS rockets. If cluster weapons cannot be used, the same operation would require using nine times as many rockets, cost nine times as much ($400,000 compared to $3.6 million), and take 40 times as long (30 seconds compared to 20 minutes) to execute.[98] The U.S. suspended operational use of cluster munitions in 2003, and the U.S. Army ceased procurement of GMLRS cluster rockets in December 2008 because of a submunition dud rate as high as five percent. Pentagon policy was to have all cluster munitions used after 2018 to have a submunition unexploded ordnance rate of less than one percent. To achieve this, the Army undertook the Alternative Warhead Program (AWP) to assess and recommend technologies to reduce or eliminate cluster munition failures, as some 80 percent of U.S. military cluster weapons reside in Army artillery stockpiles.[97]

On 30 November 2017, the Pentagon put off indefinitely their planned ban on using cluster bombs after 2018, as they had been unable to produce submunitions with failure rates of 1% or less. Since it is unclear how long it might take to achieve that standard, a months-long policy review concluded the deadline should be postponed; deployment of existing cluster weapons is left to commanders' discretion to authorize their use when deemed necessary "until sufficient quantities" of safer versions are developed and fielded.[99][100]

Users

Countries

At least 25 countries have used cluster munitions in recent history (since the creation of the United Nations). Countries listed in bold have signed and ratified the Convention on Cluster Munitions, agreeing in principle to ban cluster bombs. Countries listed in italic have signed, but not yet ratified the Convention on Cluster Munitions.

.svg.png)

.svg.png)

.svg.png)

.svg.png)

In addition, at least two countries that no longer exist (the Soviet Union and Yugoslavia)[129] have used cluster bombs. In some cases, the responsibility or even the use of cluster munition is denied by the local government.

Non-state armed groups

Very few violent non-state actors have used cluster munitions and their delivery systems due to the complexity.[130] As of August 2019, cluster munitions have been used in conflicts by non-state actors in at least 6 countries.[130]

Producers

At least 31 nations have produced cluster munitions in recent history (since the creation of the United Nations). Many of these nations still have stocks of these munitions.[131][132] Most (but not all) of them are involved in recent wars or long unsolved international conflicts; however most of them did not use the munitions they produced. Countries listed in bold have signed and ratified the Convention on Cluster Munitions, agreeing in principle to ban cluster bombs. As of September 2018, countries marked with an Asterisk (*) officially ceased production of cluster munitions.

.svg.png)

.svg.png)

Countries with stocks

As of September 2018, at least 57 countries have stockpiles of cluster munitions.[131][132] Countries listed in bold have signed and ratified the Convention on Cluster Munitions, agreeing in principle that their stockpiles should be destroyed. Countries listed in italic have signed, but not yet ratified the Convention on Cluster Munitions; countries marked with an Asterisk (*) are in the process of destroying their stockpiles.

Financers

According to BankTrack, an international network of NGOs specializing in control of financial institutions, many major banks and other financial corporations either directly financed, or provided financial services to companies producing cluster munition in 2005–2012. Among other, BankTrack 2012 report[182] names ABN AMRO, Bank of America, Bank of China, Bank of Tokyo Mitsubishi UFJ, Barclays, BBVA, BNP Paribas, Citigroup, Commerzbank AG, Commonwealth Bank of Australia, Crédit Agricole, Credit Suisse Group, Deutsche Bank, Goldman Sachs, HSBC, Industrial Bank of China, ING Group, JPMorgan Chase, Korea Development Bank, Lloyds TSB, Merrill Lynch, Morgan Stanley, Royal Bank of Canada, Royal Bank of Scotland, Sberbank, Société Générale, UBS, Wells Fargo.

Many of these financial companies are connected to such producers of cluster munitions as Alliant Techsystems, China Aerospace Science and Technology Corporation, Hanwha, Norinco, Singapore Technologies Engineering, Textron, and others.[183]

According to Pax Christi, a Netherlands-based NGO, in 2009, around 137 financial institutions financed cluster munition production.[184] Out of 137 institutions, 63 were based in the US, another 18 in the EU (the United Kingdom, France, Germany, Italy etc.), 16 were based in China, 4 in Singapore, 3 in each of: Canada, Japan, Taiwan, 2 in Switzerland, and 4 other countries had 1 financial institution involved.[185]

See also

References

Citations

- "Treaty status – The Treaty – CMC". www.stopclustermunitions.org. Retrieved 15 May 2018.

- "States Parties and Signatories by region". 12 January 2011. Retrieved 15 May 2018.

- Rogers, James I. (2013-06-21). "Remembering the terror the Luftwaffe's butterfly bombs brought to the North". The Guardian. ISSN 0261-3077. Retrieved 2017-02-09.

- Austria bans cluster munitions, International Herald Tribune, 7 Dec 2007

- Cluster Weapons; Convenience or necessity? Archived October 4, 2006, at the Wayback Machine

- Global Security.org LBU-30

- Loy, Irwin (7 December 2010). "Vietnam's Cluster Bomb Shadow". GlobalPost. Tokyo. Retrieved 29 July 2012.

- MacKinnon, Ian (3 December 2008). "Forty years on, Laos reaps bitter harvest of the secret war". The Guardian. London. Retrieved 29 July 2012.

- Eaton, Daysha (6 June 2010). "In Vietnam, cluster bombs still plague countryside". GlobalPost. Boston, MA. Retrieved 29 July 2012.

- "The HALO Trust – A charity specialising in the removal of the debris of war :: British Embassy, Yerevan, holds event for HALO". Archived from the original on 2012-12-26. Retrieved 15 May 2018.

- "404 – ICBL". www.the-monitor.org. Retrieved 15 May 2018.

- "HALO begins emergency clearance in Nagorno Karabakh". Mine Free NK. Retrieved 15 May 2018.

- Brady, Brian (2007-09-16). "Nato comes clean on cluster bombs". The Independent. London. Retrieved 2011-04-16.

- SRBIJI NE PRETE SAMO KASETNE BOMBE Archived 2011-07-22 at the Wayback Machine, (in Serbian only)

- "404 – CMC". www.stopclustermunitions.org. Retrieved 15 May 2018.

- Martin, Scott. "Obama moves to legalize cluster munitions". Retrieved 15 May 2018.

- "Cluster bombs remain in 69 nations". Retrieved 15 May 2018.

- "Iraq: Cluster Treaty Approval Should Inspire Neighbors to Join". 9 December 2009. Retrieved 15 May 2018.

- "Estados Unidos – Cientos de muertes de civiles en Irak pudieron prevenirse". 11 December 2003. Retrieved 15 May 2018.

- Wiseman, Paul (16 December 2003). "Cluster bombs kill in Iraq, even after shooting ends". USA Today.

- Wiseman, Paul (16 December 2003). "Cluster bombs kill in Iraq, even after shooting ends". USA Today.

- MCC | Cluster Bombs Archived November 21, 2006, at the Wayback Machine

- "Use of Cluster Bombs Is Confirmed by Israel". The New York Times. 1982-06-28. Retrieved 2010-03-27.

- "President Reagan News Conferences & Interviews on the Middle East/Israel (1982)". www.jewishvirtuallibrary.org. Retrieved 15 May 2018.

- "Lebanon/Israel: Hezbollah Hit Israel with Cluster Munitions During Conflict". 18 October 2006. Retrieved 15 May 2018.

- "State snubbed war victim, family says". Ynet. 30 August 2007. Archived from the original on 2 June 2008. Retrieved 13 July 2008.

- Beehner, Lionel (2006-11-21). "The Campaign to Ban Cluster Bombs". cfr.org. Council on Foreign Relations. Retrieved 2020-02-17.

- Hasson, Nir; Rapoport, Meron (2006-11-20). "Halutz Orders Probe Into Use of Cluster Bombs in Lebanon". Haaretz. Tel Aviv. Retrieved 2020-02-17.

- "Israeli Cluster Munitions Hit Civilians in Lebanon". HRW. 2006-07-24.

- "Middle East: Rice Calls For A 'New Middle East'". Radio Free Europe. 2006-07-25.

- "EXTRA: Israel defends use of cluster munitions." Deutsche Presse-Agentur. 25 July 2006. Politics. 19 August 2006. LexisNexis Academic.

- Friedman, Ina. "Deadly Remnants." The Jerusalem Report 13 November 2006: 20–22

- Staff, SPIEGEL (15 September 2008). "Did Saakashvili Lie?: The West Begins to Doubt Georgian Leader". Retrieved 15 May 2018 – via Spiegel Online.

- Georgia, Civil. "Civil.Ge -". www.civil.ge. Retrieved 15 May 2018.

- Georgia, Civil. "Civil.Ge – MoD Says it Used Cluster Bombs, but not in Populated Areas". www.civil.ge. Retrieved 15 May 2018.

- "Georgia: Russian Cluster Bombs Kill Civilians (Human Rights Watch, 14-8-2008)". www.hrw.org. Retrieved 15 May 2018.

- Russia "used cluster bombs" in Georgia – rights group, Reuters, August 15, 2008

- Dutch government report on Storimans death concludes cluster bomb propelled by Russian SS-26 (pdf) Archived June 9, 2010, at the Wayback Machine

- Taylor, Jerome These indiscriminate killers leave their deadly legacy from Libya to Lebanon The Independent, 16 August 2011, Retrieved 17 August 2011

- Chivers, C. J. (15 April 2011). "Qaddafi Troops Fire Cluster Bombs into Civilian Areas". New York Times. Retrieved 15 April 2011.

- Chivers, C.J. "Down the Rabbit Hole: Qaddafi's Cluster Munitions and the Age of Internet Claims". The New York Times, June 23, 2011. Retrieved: July 13, 2011.

- "Syria: New Evidence Military Dropped Cluster Bombs". Human Rights Watch. October 13, 2012. Retrieved October 13, 2012.

- "Cluster Bomb Usage Rises Significantly Across Syria". Brown Moses Blog. October 13, 2012. Retrieved October 13, 2012.

- C. J. Chivers (December 20, 2012). "Syria Unleashes Cluster Bombs on Town, Punishing Civilians". The New York Times. Retrieved December 21, 2012.

- Sewell Chan (September 1, 2016). "Report Finds Ban Hasn't Halted Use of Cluster Bombs in Syria or Yemen". The New York Times. Retrieved June 12, 2019.

- "Ugandan army won’t take part in cluster bomb investigation: spokesperson", Sudan Tribune, 19 Feb 2014

- "Ukraine: Widespread Use of Cluster Munitions". HRW. October 12, 2014.

- "Saudi Arabia admits it used UK-made cluster bombs in Yemen". The Guardian. 19 December 2016.

- "Yemen: Saudi Arabia used cluster bombs, rights groups says". BBC News. 3 May 2015.

- "Saudis 'used cluster bombs' in Yemen". 3 May 2015. Retrieved 15 May 2018 – via www.bbc.com.

- "Saudi-Led Group Said to Use Cluster Bombs in Yemen". 3 May 2015. Retrieved 15 May 2018 – via NYTimes.com.

- "Saudi Arabia uses terrorism as an excuse for human rights abuses". Al Jazeera America. December 3, 2015.

- "Cluster Munition Coalition – Take Action – CMC". www.stopclustermunitions.org. Retrieved 15 May 2018.

- "Cluster Bomb Fact Sheet". Legacies of War. Archived from the original on 2019-11-01. Retrieved 2019-11-05.

- "International Committee of the Red Cross". 3 October 2013. Retrieved 15 May 2018.

- "クイーンズスリムHMBって楽天で購入可能?※94%オフはここから". www.clusterbombs.org. Archived from the original on 2018-05-16. Retrieved 15 May 2018.

- "konsoleH :: Login". en.handicapinternational.be. Archived from the original on 11 October 2017. Retrieved 15 May 2018.

- "M26 Multiple Launch Rocket System (MLRS)". Retrieved 15 May 2018.

- "Off Target: The Conduct of the War and Civilian Casualties in Iraq" (PDF). Human Rights Watch. December 2003. Retrieved 2009-06-22. Cite journal requires

|journal=(help) - "Summary of Judgement for Milan Martic". International Criminal Tribunal for the Former Yugoslavia. June 2007. Archived from the original on December 15, 2007. Cite journal requires

|journal=(help) - 1 Office of the Under Secretary of Defense for Acquisition, Technology, and Logistics, "Unexploded Ordnance Report," table 2-3, p. 5. No date, but transmitted to the U.S. Congress on February 29, 2000

- "Operation Desert Storm: Casualties Caused by Improper Handling of Unexploded U.S. Submunitions" (PDF). US General Accounting Office. August 1993. Retrieved 2006-09-01. Cite journal requires

|journal=(help) - "Cluster Munitions a Foreseeable Hazard in Iraq". Human Rights Watch Briefing Paper. Retrieved 2011-07-13.

- "'Million bomblets' in S Lebanon". BBC. 2006-09-26. Retrieved 2006-09-26.

- "Army RDT&E Budget Item Justification, Item No. 177, MLRS Product Improvement Program" (PDF). Defense Technical Information Center. February 1993. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2007-06-28. Retrieved 2006-09-01. Cite journal requires

|journal=(help) - Jane's Ammunition Handbook 1994 page 362

- Clear Path International: Assisting Landmine Survivors, their Families and their Communities

- Laos: the enduring threat from cluster munitions Archived August 22, 2010, at the Wayback Machine

- "Kosovo mine expert criticises Nato". BBC News. 2000-05-23. Retrieved 2010-04-30.

- "Israeli Cluster Munitions Hit Civilians in Lebanon (Human Rights Watch, 24-7-2006)". www.hrw.org. Retrieved 15 May 2018.

- "UKWGLM_18377.pdf" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 2012-04-11. Retrieved 15 May 2018.

- Cluster Munition Monitor 2019 (PDF). International Campaign to Ban Landmines – Cluster Munition Coalition. August 2019. p. 37–39. ISBN 978-2-9701146-5-9. Retrieved 2020-02-17.

- "Eritrea Cluster Munition Ban Policy". the-monitor.org. 26 June 2018. Retrieved 27 September 2018.

- "Ethiopia Cluster Munition Ban Policy". the-monitor.org. 26 June 2018. Retrieved 27 September 2018.

- "The Norwegian Government's initiative for a ban on cluster munitions". The Norwegian Ministry of Foreign Affairs. Archived from the original on January 11, 2009.

- "Webcast from the Oslo Conference on Cluster Munitions". The Norwegian Ministry of Foreign Affairs. Retrieved 2011-07-13.

- "Treaties, States parties, and Commentaries – CCW Protocol (V) on Explosive Remnants of War, 2003". www.icrc.org. Retrieved 15 May 2018.

- "Moniteur Belge – Belgisch Staatsblad". www.ejustice.just.fgov.be. Retrieved 15 May 2018.

- "CCW review conference ends with rejection of US-backed proposal for protocol that would allow cluster bomb use". Archived from the original on 2011-12-10. Retrieved 2011-11-26.

- "US-led attempt to allow cluster bomb use is rejected at UN negotiations".

- "Eitan Barak, Doomed to Be Violated? The U.S.-Israeli Clandestine End-User Agreement and the Second Lebanon War: Lessons for the Convention on Cluster Munitions". SSRN 1606304. Cite journal requires

|journal=(help) - Foulkes, Imogen (2006-11-12). "New bomb clean-up treaty begins". BBC News. Retrieved 2010-04-30.

- "Report on Lima Conference". Cluster Munition Coalition. Archived from the original on November 21, 2007.

- "Expert Meeting Report: Humanitarian, Military, Technical and Legal Challenges of Cluster Munitions". ICRC.

- "Message from Minister for Foreign Affairs, Micheál Martin T.D." www.clustermunitionsdublin.ie. Archived from the original on 19 June 2008. Retrieved 15 May 2018.

- "International ban on cluster munitions". The Norwegian Ministry of Foreign Affairs. Retrieved 2011-07-13.

- "News – Media – CMC". www.stopclustermunitions.org. Retrieved 15 May 2018.

- "United States Department of Defense". www.defenselink.mil. Retrieved 15 May 2018.

- Signing Conference Website Archived 2008-12-16 at the Wayback Machine last retrieved on 28 November 2008

- Cluster bombs: MEPs to press for signature of treaty ban Archived 2009-02-22 at the Wayback Machine last retrieved on 19 November 2008

- Convention on Cluster Munitions to enter into force on 1 August 2010 ICRC web site

- Convention on cluster munitions – convention text in English Archived August 19, 2010, at the Wayback Machine

- Hughes, Stuart (1 August 2010). "Cluster bomb ban comes into force". BBC News. Retrieved 15 May 2018.

- "Cluster Munitions Treaty to Take Effect Sunday". Archived from the original on 6 August 2010. Retrieved 15 May 2018.

- Belanger, Louis (30 July 2010). "Cluster Bombs Treaty becomes int'l law: Years of campaigning reap results". Retrieved 15 May 2018.

- Canada Post: UN chief hails Aug. 1 entry into force of treaty banning cluster bombs

- Cluster Munitions: Background and Issues for Congress – Fas.org, 30 June 2013

- "PageNotFound" (PDF). www.dau.mil. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2017-02-01. Retrieved 15 May 2018.

- US Putting Off Planned Ban on Its Use of Cluster Bombs – Military.com, 30 November 2017

- Feickert, Andrew; Kerr, Paul K. (December 17, 2017). Cluster Munitions: Background and Issues for Congress (PDF). Washington, D.C.: Congressional Research Service. Retrieved 24 January 2018.

- "Armenia Cluster Munition Ban Policy". the-monitor.org. Retrieved 27 September 2018.

- "Nagorno-Karabakh (Area) Cluster Munition Ban Policy". the-monitor.org. 26 June 2018. Retrieved 27 September 2018.

- "Azerbaijan Cluster Munition Ban Policy". the-monitor.org. 3 July 2018. Retrieved 27 September 2018.

- "Bahrain Cluster Munition Ban Policy". the-monitor.org. 3 July 2018. Retrieved 27 September 2018.

- "Yemen Cluster Munition Ban Policy". the-monitor.org. 2 August 2018. Retrieved 27 September 2018.

- "Colombia Cluster Munition Ban Policy". the-monitor.org. 26 June 2018. Retrieved 27 September 2018.

- "Colombia Cluster Munition Ban Policy". archives.the-monitor.org. 2 September 2013. Retrieved 27 September 2018.

- "Egypt Cluster Munition Ban Policy". the-monitor.org. 2 August 2018. Retrieved 27 September 2018.

- "France Cluster Munition Ban Policy". the-monitor.org. 3 July 2018. Retrieved 27 September 2018.

- "Georgia Cluster Munition Ban Policy". the-monitor.org. 26 June 2018. Retrieved 27 September 2018.

- "Iraq Cluster Munition Ban Policy". the-monitor.org. 9 July 2018. Retrieved 27 September 2018.

- "Israel Cluster Munition Ban Policy". the-monitor.org. 2 August 2018. Retrieved 27 September 2018.

- "Libya Cluster Munition Ban Policy". the-monitor.org. 2 August 2018. Retrieved 27 September 2018.

- "Morocco Cluster Munition Ban Policy". the-monitor.org. 3 July 2018. Retrieved 27 September 2018.

- "Netherlands Cluster Munition Ban Policy". the-monitor.org. 8 August 2016. Retrieved 27 September 2018.

- "Nigeria Cluster Munition Ban Policy". the-monitor.org. 2 August 2018. Retrieved 27 September 2018.

- "Nigeria Cluster Munition Ban Policy". archives.the-monitor.org. 12 August 2014. Retrieved 27 September 2018.

- "Russia Cluster Munition Ban Policy". the-monitor.org. 7 August 2018. Retrieved 27 September 2018.

- "Saudi Arabia Cluster Munition Ban Policy". the-monitor.org. 3 July 2018. Retrieved 27 September 2018.

- Edward McGill Alexander (July 2003). "Appendix A to Chapter 9 of the Cassinga Raid" (PDF). University of South Africa. Retrieved 27 September 2018. Cite journal requires

|journal=(help) - "Sri Lanka Cluster Munition Ban Policy". the-monitor.org. 9 July 2018. Retrieved 27 September 2018.

- "Sudan Cluster Munition Ban Policy". the-monitor.org. 9 July 2018. Retrieved 27 September 2018.

- "Syria Cluster Munition Ban Policy". the-monitor.org. 2 August 2018. Retrieved 27 September 2018.

- "Thailand Cluster Munition Ban Policy". the-monitor.org. 3 July 2018. Retrieved 27 September 2018.

- "United States Cluster Munition Ban Policy". the-monitor.org. 2 August 2018. Retrieved 27 September 2018.

- "Ukraine: Widespread Use of Cluster Munitions". 20 October 2014. Retrieved 15 May 2018.

- "Ukraine Cluster Munition Ban Policy". the-monitor.org. 2 August 2018. Retrieved 27 September 2018.

- Ostaptschuk, Markian (23 October 2014). "Doubts arise over HRW cluster bomb report in Ukraine". dw.com. Retrieved 27 September 2018.

- "Meeting the Challenge – I. The Technological Evolution and Early Proliferation and Use of Cluster Munitions". Human Rights Watch. 22 November 2010. Retrieved 27 September 2018.

- Cluster Munition Monitor 2019 (PDF). International Campaign to Ban Landmines – Cluster Munition Coalition. August 2019. p. 15. ISBN 978-2-9701146-5-9. Retrieved 2020-03-02.

- "Global Problem – Stockpilers of Cluster Munitions". www.stopclustermunitions.org. Cluster Munition Coalition. Retrieved 27 September 2018.

- "Overview of Article 3 (stockpile destruction) deadlines" (PDF). Convention on Cluster Munitions. September 2018. Retrieved 27 September 2018.

- "Belgium Cluster Munition Ban Policy". the-monitor.org. 29 July 2015. Retrieved 27 September 2018.

- "Bosnia and Herzegovina Cluster Munition Ban Policy". the-monitor.org. 31 July 2015. Retrieved 27 September 2018.

- "Brazil Cluster Munition Ban Policy". the-monitor.org. 26 June 2018. Retrieved 27 September 2018.

- "Chile Cluster Munition Ban Policy". the-monitor.org. 21 July 2016. Retrieved 27 September 2018.

- "China Cluster Munition Ban Policy". the-monitor.org. 3 July 2018. Retrieved 27 September 2018.

- "Croatia Cluster Munition Ban Policy". the-monitor.org. 2 August 2018. Retrieved 27 September 2018.

- "Germany Cluster Munition Ban Policy". the-monitor.org. 8 August 2016. Retrieved 27 September 2018.

- "Greece Cluster Munition Ban Policy". the-monitor.org. 3 July 2018. Retrieved 27 September 2018.

- "India Cluster Munition Ban Policy". the-monitor.org. 3 July 2018. Retrieved 27 September 2018.

- "Survey of Cluster Munitions Produced and Stockpiled". www.hrw.org. April 2007. Retrieved 27 September 2018.

- "Japan Cluster Munition Ban Policy". the-monitor.org. 10 August 2015. Retrieved 27 September 2018.

- "North Korea Cluster Munition Ban Policy". the-monitor.org. 26 June 2018. Retrieved 27 September 2018.

- "South Korea Cluster Munition Ban Policy". the-monitor.org. 2 August 2018. Retrieved 27 September 2018.

- "Pakistan Cluster Munition Ban Policy". the-monitor.org. 3 July 2018. Retrieved 27 September 2018.

- "Poland Cluster Munition Ban Policy". the-monitor.org. 3 July 2018. Retrieved 27 September 2018.

- "Romania Cluster Munition Ban Policy". the-monitor.org. 3 July 2018. Retrieved 27 September 2018.

- "Singapore Cluster Munition Ban Policy". the-monitor.org. 3 July 2018. Retrieved 27 September 2018.

- "Slovakia Cluster Munition Ban Policy". the-monitor.org. 2 August 2018. Retrieved 27 September 2018.

- "South Africa Cluster Munition Ban Policy". the-monitor.org. 2 August 2018. Retrieved 27 September 2018.

- "Spain Cluster Munition Ban Policy". the-monitor.org. 8 July 2018. Retrieved 27 September 2018.

- "Sweden Cluster Munition Ban Policy". the-monitor.org. 8 August 2016. Retrieved 27 September 2018.

- "Taiwan Cluster Munition Ban Policy". the-monitor.org. 3 August 2016. Retrieved 27 September 2018.

- "Turkey Cluster Munition Ban Policy". the-monitor.org. 9 July 2018. Retrieved 27 September 2018.

- "United Kingdom Cluster Munition Ban Policy". the-monitor.org. 12 August 2015. Retrieved 27 September 2018.

- "Algeria Cluster Munition Ban Policy". the-monitor.org. 3 July 2018. Retrieved 27 September 2018.

- "Belarus Cluster Munition Ban Policy". the-monitor.org. 26 June 2018. Retrieved 27 September 2018.

- "Botswana Cluster Munition Ban Policy". the-monitor.org. 2 August 2018. Retrieved 27 September 2018.

- "Bulgaria Cluster Munition Ban Policy". the-monitor.org. 7 August 2018. Retrieved 27 September 2018.

- "Cambodia Cluster Munition Ban Policy". the-monitor.org. 26 June 2018. Retrieved 27 September 2018.

- "Cyprus Cluster Munition Ban Policy". the-monitor.org. 3 July 2018. Retrieved 27 September 2018.

- "Estonia Cluster Munition Ban Policy". the-monitor.org. 3 July 2018. Retrieved 27 September 2018.

- "Finland Cluster Munition Ban Policy". the-monitor.org. 3 July 2018. Retrieved 27 September 2018.

- "Guinea Cluster Munition Ban Policy". the-monitor.org. 3 July 2018. Retrieved 27 September 2018.

- "Guinea Bissau Cluster Munition Ban Policy". the-monitor.org. 9 July 2018. Retrieved 27 September 2018.

- "Indonesia Cluster Munition Ban Policy". the-monitor.org. 26 June 2018. Retrieved 27 September 2018.

- "Iran Cluster Munition Ban Policy". the-monitor.org. 2 August 2018. Retrieved 27 September 2018.

- "Jordan Cluster Munition Ban Policy". the-monitor.org. 26 June 2018. Retrieved 27 September 2018.

- "Kazakhstan Cluster Munition Ban Policy". the-monitor.org. 26 June 2018. Retrieved 27 September 2018.

- "Kuwait Cluster Munition Ban Policy". the-monitor.org. 3 July 2018. Retrieved 27 September 2018.

- "Oman Cluster Munition Ban Policy". archives.the-monitor.org. 12 August 2014. Retrieved 27 September 2018.

- "Peru Cluster Munition Ban Policy". the-monitor.org. 2 August 2018. Retrieved 27 September 2018.

- "Qatar Cluster Munition Ban Policy". the-monitor.org. 3 July 2018. Retrieved 27 September 2018.

- "Serbia Cluster Munition Ban Policy". the-monitor.org. 3 July 2018. Retrieved 27 September 2018.

- "Switzerland Cluster Munition Ban Policy". the-monitor.org. 2 August 2018. Retrieved 27 September 2018.

- "Turkmenistan Cluster Munition Ban Policy". the-monitor.org. 26 June 2018. Retrieved 27 September 2018.

- "United Arab Emirates Cluster Munition Ban Policy". the-monitor.org. 9 July 2018. Retrieved 27 September 2018.

- "Uzbekistan Cluster Munition Ban Policy". the-monitor.org. 26 June 2018. Retrieved 27 September 2018.

- "Venezuela Cluster Munition Ban Policy". the-monitor.org. 9 July 2018. Retrieved 27 September 2018.

- "Zimbabwe Cluster Munition Ban Policy". the-monitor.org. 2 August 2018. Retrieved 27 September 2018.

- "Financial institutions involved in CM production process, 2012 report by BankTrack". Archived from the original on 2012-08-25. Retrieved 15 May 2018.

- "Key Findings from the November 2014 update of "Worldwide Investments in Cluster Munitions a shared responsibility" by PAX" (PDF). Retrieved 15 May 2018.

- "Report: Banks, Financial Institutions Still Funding Cluster Bomb-Making Companies with Billions of Dollars". Retrieved 15 May 2018.

- "Worldwide investments in CLUSTER MUNITIONS a shared responsibility IKV Pax Christi report update June 2012" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 2013-11-12. Retrieved 15 May 2018.

Bibliography

- Clancy, Tom (1996). Fighter Wing. London: HarperCollins, 1995. ISBN 0-00-255527-1.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Cluster munitions. |

- Cluster Munition Coalition

- Mines Advisory Group

- Cluster munitions and international humanitarian law International Committee of the Red Cross

- Convention on Cluster Munitions – Official website serving the government initiative to ban cluster munitions

- Clear Path International

- Global Security.org LBU-30

- Circle of Impact: The Fatal Footprint of Cluster Munitions on People and Communities 16 May 2007

- Disarmament Insight website

- Council on Foreign Relations: The Campaign to Ban Cluster Bombs November 21, 2006

- Hillary for, Obama against Cluster Bombs Ya Libnan December 29, 2007

- Interactive map of cluster bomb producers, stockpilers, users and affected countries

- Ban Advocates – Voices from affected communities