Struthiosaurus

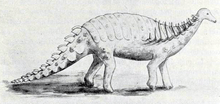

Struthiosaurus (Latin struthio = ostrich + Greek sauros = lizard) is one of the smallest known and most basal genera of nodosaurid dinosaurs, from the Late Cretaceous period (Santonian-Maastrichtian) of Austria, Romania, France and Hungary in Europe.[1] It was protected by body armour. Although estimates of its length vary, it may have been as small as 2.2 metres (7.2 ft) long.

| Struthiosaurus | |

|---|---|

| |

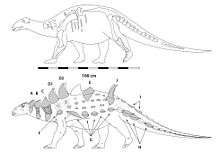

| Diagrams showing the known skeletal elements and hypothetical placement of osteoderms in S. austriacus | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Clade: | Dinosauria |

| Order: | †Ornithischia |

| Family: | †Nodosauridae |

| Subfamily: | †Struthiosaurinae |

| Genus: | †Struthiosaurus Bunzel, 1871 |

| Type species | |

| †Struthiosaurus austriacus Bunzel, 1871 | |

| Species | |

| Synonyms | |

| |

History of discovery

.jpg)

In 1859, geologist Eduard Suess at the Gute Hoffnung coal mine at Muthmannsdorf near Wiener Neustadt in Austria, discovered a dinosaur tooth on a stone pile. With the help of mine intendant Pawlowitsch it was attempted to find the source of the fossil material. The search proved fruitless at first but ultimately a thin marl layer was discovered, intersected by a obliquely sloping mine shaft, which contained an abundant number of various bones. These were subsequently excavated by Suess and Ferdinand Stoliczka. The marl was a fresh water deposit, now considered part of the Grünbach Formation.[2]

The finds were stored in the museum of the University of Vienna but received little attention until they were studied by Emanuel Bunzel in 1870. In 1871, Bunzel published a treatise describing the fossils and naming several new genera and species. One of them was the genus Struthiosaurus based on a single partial portion of the posterior end of the skull, largely consisting of the braincase. The type and only known species of the genus at the time was Struthiosaurus austriacus.[2] Bunzel stated that he only provisionally named the taxon and gave no etymology of the name. The generic name is derived from new Latin struthio, itself derived from Ancient Greek στρούθειος, stroutheios, "of the ostrich". Bunzel chose the name because of the birdlike morphology of the braincase.[2] The specific name refers to the provenance from Austria.

Apart from the braincase, Bunzel unknowingly described other material of Struthiosaurus. He recognized that there were bones and osteoderms of armoured dinosaurs among the finds and referred them to a Scelidosaurus sp. and a Hylaeosaurus sp.[2] These British genera represented the best known thyreophoran forms found at the time. Bunzel also discovered two rib fragments which had a very puzzling build. They were double-headed but the upper rib head, the tuberculum, was short and positioned in such a way that it could not possibly touch the vertebra, if the shaft was oriented in the usual vertical position. He assumed that only the lower capitulum connected to the vertebral body. A rib touching the vertebra with a single surface is normal for lizards, though in their case the rib heads are fused into a single synapophysis. Bunzel therefore concluded that the ribs belonged to a giant lizard. In analogy to Mosasaurus, the giant lizard named after the River Maas, he named this lizard Danubiosaurus anceps, after the Danube. The specific name anceps means "double-headed" in Latin, highlighting the, for a lizard, exceptional trait of having double-headed ribs.[2] In fact the ribs were those of Struthiosaurus. In Ankylosauria, the rump is so flat that the upper part of the rib shafts sticks out sideways, which rotates the short tuberculum to the diapophysis, its vertebral contact facet.

Many species have been referred to Struthiosaurus, most based on very fragmentary and nondiagnostic material. Three valid species are recognized by paleontologists: S. austriacus Bunzel, 1871, based on holotype PIWU 2349/6; S. transylvanicus Nopcsa, 1915, based on BMNH R4966, a skull and partial skeleton from Romania;[3] and S. languedocensis Garcia and Pereda-Suberbiola, 2003, based on UM2 OLV-D50 A–G CV, a partial skeleton found in 1998 in France.[4] It is the namesake of the nodosaurid subfamily Struthiosaurinae, members of which are found only in Europe.[5]

A number of invalid taxa have been shown to be junior synonyms of Struthiosaurus austriacus, most of them created when Harry Govier Seeley in 1881 revised the Austrian material.[6] They include: Danubiosaurus anceps Bunzel, 1871; Crataeomus pawlowitschii Seeley, 1881; Crataeomus lepidophorus Seeley 1881; Pleuropeltis suessii Seeley, 1881; Rhadinosaurus alcimus Seeley 1881, Hoplosaurus ischyrus Seeley 1881 and Leipsanosaurus noricus Nopcsa, 1918.[7] Another European ankylosaurid, Rhodanosaurus ludguensis Nopsca, 1929, from Campanian-Maastrichtian-age rocks of southern France, is now regarded as a nomen dubium and referred to Nodosauridae incertae sedis.[8]

The three valid species of Struthiosaurus differ from one another in that S. austriacus is smaller than S. transylvanicus and possesses less elongate cervical vertebrae. Also, though the quadrate-paroccipital process contact is fused in S. transylvanicus, it is unfused in S. austriacus. The skull of S. languedocensis is unknown, but the taxon differs from S. transylvanicus in the flatter shape of the dorsal vertebrae. It differs from S. austriacus in the shape of the ischium. (Vickaryous, Maryanska, and Weishampel 2004)

Classification

Bunzel was very puzzled by the braincase. He knew that it belonged to a reptile instead of a mammal because of a single as opposed to a double-headed occipital condyle. The back of the head was otherwise not very reptilian as it was low, compact, fused and convex in a gradual curve towards the skull-roof. Lizards had a very different, more "open", occiput. Crocodiles were more similar but still had a concave skull rear. Bunzel considered whether it might be a dinosaur but in 1871 little dinosaurian occiput material had been described and it seemed to him that their skulls in this respect were more lizard-like. The only group showing a comparable rounding and fusion of skull bones were the birds. Bunzel sent a drawing and description to Professor Thomas Huxley in London, at the time one of the few dinosaur experts. Huxley agreed that the braincase resembled that of a bird, commenting "This skull-fragment is more bird-like, than any thing [sic] I have yet seen". Knowing that Huxley had named a reptile order Ornithoscelida for forms sharing with birds certain traits in the pelvis and hindlimbs, Bunzel ended his description with the prediction that "with time, it might also be possible to create an order Ornithocephala ('Bird Heads')".[2]

Bunzel was correct in assuming an affinity with birds but this was because birds are themselves dinosaurs. In dinosaurs, the rear skull bones are generally strongly fused. Nodosaurids did convergently develop a rounded skull. As the massive quadrates were lacking, the skull fragment gave a false impression of being lightly built. Ankylosaur material at the time was typically referred to the Scelidosauridae but because this was the first ankylosaur braincase to be described, the connection was not obvious. The first to understand it represented an armoured dinosaur was Nopcsa who in 1902 placed it in the Acanthopholididae.[9] He later corrected its name to Acanthopholidae.[10] Walter Coombs in 1978 stated it was a nodosaurid.[11]

Cladistic analysis of Struthiosaurus indicates that the taxon is a basal member of the Nodosauridae and suggested it may be one of the most basal ankylosaurs in the clade Ankylosauria. An analysis by Ösi in 2005, describing the taxon Hungarosaurus, found that while being younger in age than other nodosaurids, Struthiosaurus was one of the more basal taxa, although many features could not be coded for it.[12] The cladogram below follows the most resolved topology from a 2011 analysis by paleontologists Richard S. Thompson, Jolyon C. Parish, Susannah C. R. Maidment and Paul M. Barrett.[13]

| Nodosauridae |

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

References

- Struthiosaurus in The Dinosaur Encyclopaedia at Dino Russ's Lair

- Bunzel, E (1871). "Die Reptilfauna der Gosaformation in der Neuen Welt bei Wiener-Neustadt" (PDF). Abhandlungen der Kaiserlich-Königlichen Geologischen Reichsanstalt. 5: 1–18.

- F. Nopcsa, 1915, "Die dinosaurier der Siebenbürgischen landesteile Ungarns", Mitteilungen aus dem Jahrbuche der Königlich-Ungarischen Geologischen Reichsanstalt 23: 1-24

- G. Garcia and X. Pereda-Suberbiola, 2003, "A new species of Struthiosaurus (Dinosauria: Ankylosauria) from the Upper Cretaceous of Villeveyrac (southern France)", Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology 23(1): 156-165

- Kirkland, J. I.; Alcalá, L.; Loewen, M. A.; Espílez, E.; Mampel, L.; Wiersma, J. P. (2013). Butler, Richard J, ed. "The Basal Nodosaurid Ankylosaur Europelta carbonensis n. gen., n. sp. From the Lower Cretaceous (Lower Albian) Escucha Formation of Northeastern Spain". PLoS ONE 8 (12): e80405.

- H.G. Seeley, 1881, "The reptile fauna of the Gosau Formation preserved in the Geological Museum of the University of Vienna", Quarterly Journal of the Geological Society of London 37(148): 620-707

- F. Nopcsa, 1918, "Leipsanosaurus n. gen. ein neuer thyreophore aus der Gosau", Földtani Közlöny 48: 324-328

- Pereda-Suberbiola, X., and Galton, P. M., 2001. Reappraisal of the nodosaurid ankylosaur Struthiosaurus austriacus Bunzel, 1871 from the Upper Cretaceous Gosau Beds of Austria. pp. 173-210 In: Carpenter, K., (ed.) The Armored Dinosaurs. Indiana University Press, Bloomington & Indianapolis, 2001, pp. xv-526

- F. Nopcsa. 1902. "Notizen über cretacische Dinosaurier". Sitzungsberichte der Mathematisch-Naturwissenschaftlichen Classe der Kaiserlichen Akademie der Wissenschaften III(1): 93-114

- Nopcsa, B.F. (1928). "Palaeontological notes on reptiles. V. On the skull of the Upper Cretaceous dinosaur Euoplocephalus". Geologica Hungarica, Series Palaeontologica. 1 (1): 1–84.

- W.P. Coombs. 1978. "Forelimb muscles of the Ankylosauria (Reptilia, Ornithischia)". Journal of Paleontology 52(3): 642-657

- Ösi, A. (2005). "Hungarosaurus tormai, a new ankylosaur (Dinosauria) from the Upper Cretaceous of Hungary". Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology. 25 (2): 370–383. doi:10.1671/0272-4634(2005)025[0370:HTANAD]2.0.CO;2.

- Richard S. Thompson; Jolyon C. Parish; Susannah C. R. Maidment; Paul M. Barrett (2011). "Phylogeny of the ankylosaurian dinosaurs (Ornithischia: Thyreophora)". Journal of Systematic Palaeontology. 10 (2): 301–312. doi:10.1080/14772019.2011.569091.