Nodosauridae

Nodosauridae is a family of ankylosaurian dinosaurs, from the Late Jurassic to the Late Cretaceous period of what are now North America, Europe, Asia, Africa, and Antarctica.

| Nodosaurids | |

|---|---|

| |

| Gargoyleosaurus skeleton cast | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Clade: | Dinosauria |

| Order: | †Ornithischia |

| Suborder: | †Ankylosauria |

| Family: | †Nodosauridae Marsh, 1890 |

| Subgroups | |

| Synonyms | |

|

Acanthopholididae Nopcsa, 1902 | |

Description

Nodosaurids, like their close relatives the ankylosaurids, were heavily armored dinosaurs adorned with rows of bony armor nodules and spines (osteoderms), which were covered in keratin sheaths. All nodosaurids, like other ankylosaurians, were medium-sized to large, heavily built, quadrupedal, herbivorous dinosaurs, possessing small, leaf-shaped teeth. Unlike ankylosaurids, nodosaurids lacked mace-like tail clubs, instead having flexible tail tips. Many nodosaurids had spikes projecting outward from their shoulders. One particularly well-preserved nodosaurid "mummy", known as the Suncor nodosaur (Borealopelta), preserved a nearly complete set of armor in life position, as well as the keratin covering and mineralized remains of the underlying skin, which indicate the animal had red and white camouflage.[1][2]

Classification

The family Nodosauridae was erected by Othniel Charles Marsh in 1890, and anchored on the genus Nodosaurus.[3][4]

The clade Nodosauridae was first defined by Paul Sereno in 1998 as "all ankylosaurs closer to Panoplosaurus than to Ankylosaurus," a definition followed by Vickaryous, Teresa Maryańska, and Weishampel in 2004. Vickaryous et al. considered two genera of nodosaurids to be of uncertain placement (incertae sedis): Struthiosaurus and Animantarx, and considered the most primitive member of the Nodosauridae to be Cedarpelta.[5] The cladogram below follows the most resolved topology from a 2011 analysis by paleontologists Richard S. Thompson, Jolyon C. Parish, Susannah C. R. Maidment and Paul M. Barrett.[6] The placement of Polacanthinae follows its original definition by Kenneth Carpenter in 2001.[7]

| Nodosauridae |

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

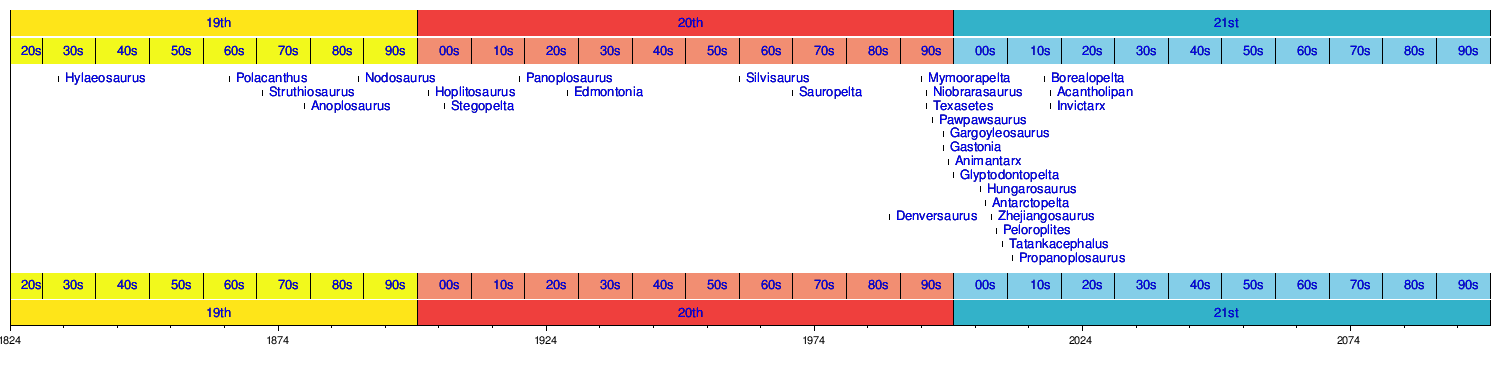

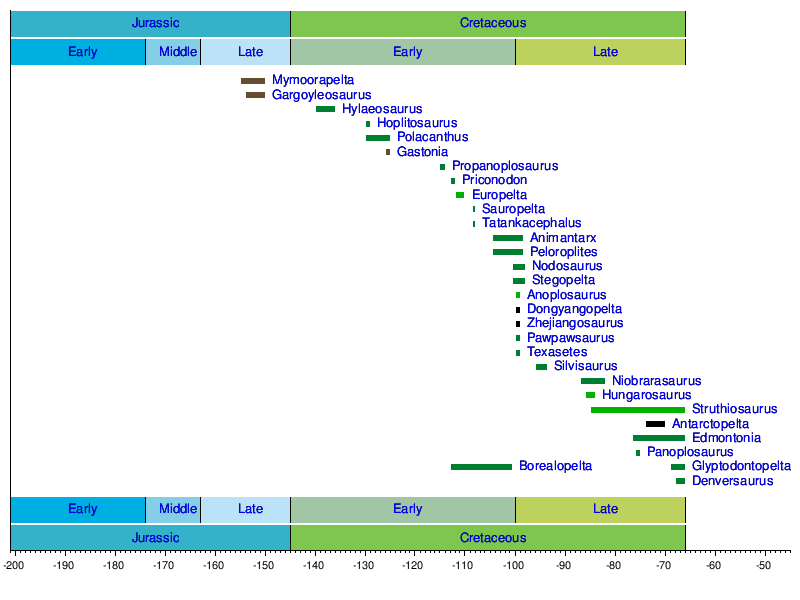

Timeline

Biogeography

The near simultaneous appearance of nodosaurids in both North America and Europe is worthy of consideration. Europelta is the oldest nodosaurid from Europe, it is derived from the lower Albian Escucha Formation. The oldest western North American nodosaurid is Sauropelta, from the lower Albian Little Sheep Mudstone Member of the Cloverly Formation, at an age of 108.5±0.2 million years. Eastern North American fossils seem older. Teeth of Priconodon crassus from the Arundel Clay of the Potomac Group of Maryland, which dates near the Aptian–Albian boundary. The Propanoplosaurus hatchling from the base of the underlying Patuxent Formation, dating to the upper Aptian, is the oldest known nodosaurid.[3]

Polacanthids are known from pre-Aptian fauna from both Europe and North America. The timing of the appearance of nodosaurids on both continents indicates that the origins of the clade preceded the isolation of North America and Europe, pushing the group's date of evolution back to at least the "middle" Aptian. The separation of Nodosauridae into European Struthiosaurinae and North American Nodosaurinae by the end of the Aptian provides a revised date for the isolation of the continents from each other by rising sealevels.[3]

Below is a table showing the age difference between continents. North American nodosaurids are teal, European nodosaurids are green, European polacanthids are blue, and North American polacanthids are brown. Other nodosaurids or polacanthids are black. This table supports the observations by Kirkland et al. (2013).[3]

- James Kirkland et al. considers Mymoorapelta, Gargoyleosaurus, Hylaeosaurus, Polacanthus, Hoplitosaurus and Gastonia to be Polacanthids, outside of Nodosauridae.[3]

See also

References

- Smith, Craig S. (12 May 2017). "'Dinosaur Mummy' Emerges From the Oil Sands of Alberta". The New York Times. Retrieved 31 May 2017.

- Davis, Nicola (2017-08-03). "Heavily armoured dinosaur had ginger camouflage to deter predators – study". The Guardian. ISSN 0261-3077. Retrieved 2017-12-01.

- Kirkland, J. I.; Alcalá, L.; Loewen, M. A.; Espílez, E.; Mampel, L.; Wiersma, J. P. (2013). Butler, Richard J (ed.). "The Basal Nodosaurid Ankylosaur Europelta carbonensis n. gen., n. sp. From the Lower Cretaceous (Lower Albian) Escucha Formation of Northeastern Spain". PLoS ONE. 8 (12): e80405. Bibcode:2013PLoSO...880405K. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0080405. PMC 3847141. PMID 24312471.

- Burns, Michael E. (2008). "Taxonomic utility of ankylosaur (Dinosauria, Ornithischia) osteoderms: Glyptodontopelta mimus Ford, 2000: a test case". Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology. 28 (4): 1102–1109. doi:10.1671/0272-4634-28.4.1102.

- Vickaryous, M. K., Maryanska, T., and Weishampel, D. B. (2004). Chapter Seventeen: Ankylosauria. in The Dinosauria (2nd edition), Weishampel, D. B., Dodson, P., and Osmólska, H., editors. University of California Press.

- Richard S. Thompson; Jolyon C. Parish; Susannah C. R. Maidment; Paul M. Barrett (2011). "Phylogeny of the ankylosaurian dinosaurs (Ornithischia: Thyreophora)". Journal of Systematic Palaeontology. 10 (2): 301–312. doi:10.1080/14772019.2011.569091.

- Carpenter K (2001). "Phylogenetic analysis of the Ankylosauria". In Carpenter, Kenneth (ed.). The Armored Dinosaurs. Indiana University Press. pp. 455–484. ISBN 978-0-253-33964-5.

Further reading

- Carpenter, K. (2001). "Phylogenetic analysis of the Ankylosauria." In Carpenter, K., (ed.) 2001: The Armored Dinosaurs. Indiana University Press, Bloomington & Indianapolis, 2001, pp. xv-526

- Osi, Attila (2005). Hungarosaurus tormai, a new ankylosaur (Dinosauria) from the Upper Cretaceous of Hungary. Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology 25(2):370-383, June 2003.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Nodosauridae. |